Hatice Karaaslan, Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University School of Foreign Languages, Ankara, Turkey

Karaaslan, H. (2019). Mentoring to promote professional well-being. Relay Journal, 2(2), 306-318. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020206

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

This article elaborates on a follow-up mentoring session conducted with a junior colleague who had frequent contact with me over a period of one year during her coursework as she considered me a senior instructor with substantial research experience. The purpose was to exploit the strategies of advising in a mentoring context utilizing intentional reflective dialogue (IRD) to encourage reflection on professional well-being. To facilitate the process and achieve an in-depth analysis of her level of professional well-being, I employed Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model, explaining professional well-being with reference to its components of positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment. In the article, I briefly give information on the context and background, the purpose, and the professional well-being model used. I then outline the flow of the session, and point out and discuss how the strategies of advising have been exploited through a series of IRD exchanges in an effort to stimulate an in-depth discussion. Finally, I present my personal reflections as well as the potential implications to be considered while conducting mentor-mentee sessions and improving professional well-being in educational settings.

Context, Background, and Purpose

This one-to-one mentoring session was held upon the completion of the four-module Learning Advisor Training Program, including Course 1 Getting Started, Course 2 Going Deeper, Course 3 Becoming Aware, and Course 4 Transformation, offered by the trainers, Jo Mynard and Satoko Kato, from Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) in Japan and completed by the English language instructors from Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University School of Foreign Languages (AYBU-SFL) in Turkey.

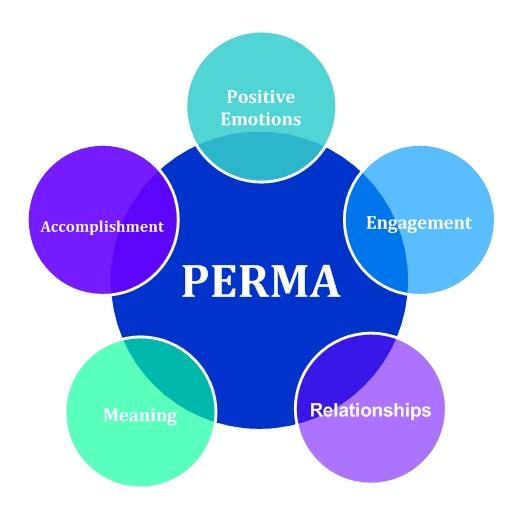

The goal was to experiment with the idea of exploiting the strategies of advising in a mentoring context utilizing intentional reflective dialogue (IRD) to encourage reflection on my colleague’s professional well-being. Engaging in reflective dialogue with others, unlike self-reflection, helps one to critically observe oneself by adopting multiple/new perspectives and challenging one’s deeply rooted values, assumptions, and beliefs; as such, it may result in potentially more transformative learning (Kato, 2012; Kato & Mynard, 2015; MacDonald, 2019). In a mentoring situation, though, knowledge and skills transfer is also included, different from an advising context where the main goal is listening by asking questions. Additionally, to further facilitate this process and achieve an in-depth analysis of her level of professional well-being with reference to a framework, I employed Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model (Figure 1), providing a conceptual explanation for professional well-being and including the components of positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment.

Accordingly, the session was conducted with an English language instructor from a public university in Turkey who had volunteered to take part in the exercise, and with whom I had a mentoring session of 1.5 hours. She was a moderately experienced instructor in her seventh year at the institution enthusiastically pursuing her professional development activities including graduate studies and certified courses in her field. She had frequent contact with me over a period of one year during her coursework both face-to-face and online, in the form of a mentor-mentee relationship as she considered me a senior instructor with substantial research experience.

The PERMA Model

The PERMA model in Figure 1 below, rooted in positive psychology, entails that good feelings help us maintain good physical health with an optimistic and hopeful outlook on life and perform better at work.

Figure 1. Elements of the PERMA model (Seligman, 2011)

Unlike positive emotions broadening our mindsets and opening us to new possibilities, negative emotions limit our focus and hinder our creativity (Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005). In addition to emotional well-being, the model also focuses on the importance of meaningful engagement, which refers to dealing with the things we enjoy doing or care about most, and building strong networks of relationships around us with people who pursue shared goals. These contribute to productivity, meaningfulness and a sense of achievement in life.

As such, positive emotions and meaningful engagement are the essential elements that enable individuals to flourish and contribute to their organizations in significant ways and thus important issues that require critical consideration on the part of directors, coordinators, trainers or mentors in educational institutions. It is important that such actors understand instructor psychology, not only that of the learner. These considerations help promote instructors’ professional well-being allowing them space, time, and energy to develop as people through the realization of potential and self-acceptance, build autonomy, be fulfilled and satisfied with life, establish positive relationships with others, and make a contribution to the community (Ryff, 1989; Shah & Marks, 2004; Pollard & Lee, 2003).

Consequently, the purpose of the current session under scrutiny was two-fold: reflecting on our mentor-mentee experience together during my mentee’s recently completed graduate studies, as well as on her professional well-being in general.

Building IRD on a Common Ground to Promote Professional Well-being

My mentee and I had known each other for quite a long time. Throughout our acquaintance, we have kept our relationship at a professional level building on a senior-junior connection in which we had strong bonds of trust and rapport. I imagined that the professional, yet trusting nature of our relationship would help her to reflect on our mentor-mentee experience. However, I was not sure whether she would be able to open up equally comfortably about her professional well-being which would cover a much larger scope, including her professional and possibly personal life.

I built our mentor-mentee dialogue intentionally, and in my first questions I wanted to encourage her to look at the big picture by linking different aspects of her life, as an advising strategy. For example, through the dialogue we were able to explore her life before she started her graduate studies, and even prior to the time she decided to take up some certified field-specific courses, and to find recognition in language teaching contexts, especially in higher education, as illustrated in Extract 1 below.

Extract 1: Reflecting on professional and personal transformation

Mentor: So when you compare your two selves: you before thesis and you after thesis, do you think you have transformed in any way? [Metaview/linking to encourage the mentee’s sense of self-awareness and transformation]

Mentee: I have gone through a step-by-step process; even my personality has changed; the process has contributed to me in many ways, not only in the academic sense but also in human relations, following you as a role model. [Both laughing] Personally, completing their studies and learning new things are things that make people happy; I have realized this. Also, I have learned to be more positive and optimistic in human relations. In professional terms, you have helped me learn by doing and discovering, giving feedback, conducting research; these are the skills that are necessary for people working in a university context, but I have just realized this; in whatever you suggested for improvement, there was some logic and I worked on them happily.

Mentor: Well thank you. So, going back: What made you engage in further professional development, resuming your graduate studies or doing certified courses in your field? What made you go back and start these studies again after you gave it up years ago? [Asking powerful questions to encourage the mentee to open up further as well as complimenting indirectly by pointing out a positive element of the situation -engaging in further professional development- that might be otherwise missed]

Mentee: Certified courses taught me many things; then I thought I was doing something really good into English language teaching there, and I had already worked on gender in my unfinished graduate studies. These field-specific courses gave me this idea to take it up again. I failed twice in my thesis defense meetings before due to advisor issues and for that I didn’t think of taking it up again, but then with these new courses, I started to think that it would be good for my professional development.

Mentor: So, these field-specific courses motivated you to get started again.. [Restating to let the mentee hear the mentor’s interpretation of the situation and hold on to her motives tightly]

Mentee: Yes. I needed to improve myself with some hands-on practice after seven years of teaching; I realized that I was repeatedly using the same techniques, so I decided to start these courses. Some other colleagues found it boring or not that beneficial but I personally learned a lot from all my assignments and observation activities. Probably I was late in pursuing professional development, but maybe I valued it even more after that break; I studied being aware of my needs; I think positively about it.

Mentor: I agree dear; for instance I had my master’s right after my undergrad degree, but with my PhD I took it easy, spread it over years; seeing academic work as a natural aspect of life appealed to me more. [Experience-sharing to introduce alternatives and allow real learning priorities to surface]

Mentee: You like both academic work and teaching at the same time. You realized the importance of professional development at the very beginning but I learned it over time. In fact, my previous workplace, a private university, had a strict and well-defined structure and everybody did the same thing, like a machine, so you had to stick to it. But here [in the current workplace], there is autonomy, and this independence motivates you to develop yourself.

The timely use of advising strategies such as restating, linking, experience-sharing, asking powerful questions and complimenting proved effective in revealing my mentee’s main motivation behind her professional development efforts, the desire to expand her repertoire of teaching tools and gain new insights and perspectives in a stress-free environment that allows teacher autonomy and ownership. She could also elaborate on her transformation both professionally and personally, describing the skills she had to develop during her studies and would use in her current academic context, as well as adopting a more positive perspective in human relations and towards the institution in general.

In this naturally emerging positive climate of transformation resulting from her professional development pursuits, I wanted to establish a link between this series of reflective exchanges between the mentee and the mentor, and the various aspects of professional well-being as described in Seligman’s PERMA model (2011). At this stage, it seemed to be quite the right time to try the strategy of intuiting as shown in Extract 2 below in an effort to encourage her to reflect on the “positive emotions” component of the PERMA model. It was again at this point that I introduced this model of professional well-being briefly and told her that I would be making references to the various dimensions of it as we elaborate further on her professional development and transformation activities in relation to our mentor-mentee relationship.

Extract 2: Reflecting on positive emotions

Mentor: Mmm, so you are happy in a place like this. Are you happy here? [Intuiting to allow emotions to surface]

Mentee: I’m happy. Compared to my previous workplace, I am happy and pleased, with the management, their approaches. There are some minor things but I think all workplaces have them anyway.

Mentor: You are saying that you are happy but there are some minor things. Do you ever get to talk about them with your director? Do you think they are not that important? [Repeating/restating to express empathy and make sure the mentee feels she is being listened to as well as challenging/confronting to encourage the mentee to challenge herself]

Mentee: I might get some explanation, but in fact I just think not much will change even if I talk about them. But like I said I am happy in general; when there is too much strict structure in everything as in my previous workplace, there is too much stress but no autonomy.

Mentor: So considering these are your feelings in general, how would you assess your level of “positive emotions” on a scale of 1-10? [Asking a powerful question to allow emotions to surface]

Mentee: Around 7 or 8. And the main reason is not having that much stress. If the director were at school 7/24, I would be stressed probably. I like the director as a person.

Mentor: Don’t you think if you spent more time and developed rapport with your director, it would be easier for you to open up and talk about your issues more comfortably? [Challenging the mentee with powerful, hypothetical questions to encourage perspective shift or introduce alternatives]

Mentee: Perhaps yes. I don’t visit him if I don’t have to [although he has an open door policy). I guess it is because of me.

The utilization of advising strategies including intuiting, challenging, and using powerful, hypothetical questions helped her to visualize her emotional state in her current workplace and name it as “happy and pleased”, as opposed to those felt in the previous one, and she was motivated to provide quite a high rating (7-8) for the “positive emotions” component of the PERMA model on the 1-10 scale offered by the mentor, mainly due to the stress-free environment that allows teacher autonomy and ownership. Despite this overall positive state, she was reluctant to visit the director to talk about some issues she had thinking that they are insignificant, on which follow-up mentor-mentee sessions could be built.

Closely linked with the idea of achieving positive emotions in a workplace is building strong networks of relationships and surrounding ourselves with people who pursue shared goals and lead a productive and meaningful life; therefore, I guided her to describe her workplace relationships as in Extract 3 below.

Extract 3: Reflecting on relationships

Mentor: When it comes to your colleagues, do you spend time with them? I don’t mean only the ones that you are in direct contact like the ones in your office. Do you chat with them comfortably or get support?

Mentee: I’m a sociable person, I have contact with everybody.

Mentor: Are communication channels to enhance professional relationships open in your workplace? Think of your experiences or needs. [Asking a powerful question to encourage the mentee to open up]

Mentee: I don’t share profession-related ideas much; it is probably because we don’t have strict working hours; we teach at different times during the day and we don’t have to stay in our office at other times.

Mentor: Would you like to stay at your office more and meet your needs with respect to professional bonds? [Challenging the mentee to introduce alternatives to improve professional bonds]

Mentee: I may not like the idea of strict working hours because I can do some of my work at home or at another place. I like it better to go home after my classes and start working on student papers or preparing for my classes after some rest. This way I can also use my time flexibly and spare time for family, friends, my studies or interests.

Mentor: Then, how would you assess your level of “relationships” on a scale of 1-10? [Asking a powerful, hypothetical question to encourage the mentee to look at the big picture and assess her relationships in the workplace]

Mentee: It would be 8. I’m pleased with the current situation; I believe my professional bonds with my colleagues are good, and I meet my needs in this sense. We have face-to-face weekly meetings, email and WhatsApp groups through which we share ideas and documents.

My mentee seemed to be contented with the kind of relationships she had and how they are managed at her workplace, which is an important aspect of professional well-being, especially in her case as she can spare time for her professional development activities.

My next focus during the session would be the “engagement” component of the model, and thus I asked about her level of meaningful and productive engagement in her workplace as shown in Extract 4 below.

Extract 4: Reflecting on engagement

Mentor: You know we engage in this profession in various ways, during classes, outside the classroom, before or after lessons, from teaching to thinking about student issues to working toward graduate studies or completing course assignments, it is all about some aspect of this profession. When you consider all of these, by working in this institution, do you think you are adequately and meaningfully engaged? [Linking various aspects of the profession and challenging the mentee to develop her capacity for self-awareness and to allow real priorities to surface]

Mentee: In the past, I used to be interested in my students more, but now I feel tired, I guess because of my teaching load. I asked for extra classes to teach in my instutition to earn more money. I know this is a personal situation but especially recently I feel this way.

Mentor: Don’t you think you are more experienced now and thus have become more practical, while preparing materials or have improved your compensation strategies, and thus need less time for preparation? [Complimenting and pointing out a positive element in a realistic way to make the mentee feel good about herself]

Mentee: Well yes, with experience you learn more and become practical, but I have motivational issues. Teaching many hours made me tired, I guess. And teaching at the school of foreign languages also has a repetitive nature; perhaps this is also boring. I might like to get a different job, offering limited contact with people, maybe something in nature. I have good rapport with my students, though, and do my job in the class.

Mentor: What do you think is the optimum number of teaching hours for you to avoid such burnout? Have you ever thought about talking to the director about this? [Confronting to introduce alternatives or to allow real priorities to surface]

Mentee: 15 hours weekly, but I want to have the extra hours myself [there are things she wants to do and that’s why she wants to earn extra money by teaching more hours in her institution; real priorities emerging]; for family, personal issues; nothing to do with the school.

Mentor: And how would you rate your engagement level on a scale of 1-10, again?

Mentee: 8. The school is great, I’m happy here. One day if I develop an interest in something other than teaching as a profession, I might go for that.

This phase was quite challenging for me or us in that, as we uncovered through the use of advising strategies such as linking, challenging/confronting and complimenting, my mentee was, compared to her previous years of teaching, seemingly less interested in the specific profession of teaching while on the other hand she was intensively pursuing professional development in her field, quite a contradiction when considered solely on its own. However, as we all may have experienced many times, a dialogue does not unfold in a vacuum; a new meaning is formed when a person addresses another in a reflective dialogue (Bakhtin, 1986, cited in Yamashita & Mynard, 2015); there are always non-verbal messages, posture and facial expressions more revealing in this context. In her reflection and expression, she had all that fatigue showing itself in everything about her, tone of voice, intonation, pitch, gaze and color. Therefore, as the mentor, I needed to draw her attention to this contradiction, and help her find the root cause of this feeling of lethargy as illustrated in Extract 5 below.

Extract 5: Reflecting on meaning and accomplishment

Mentor: Then, is teaching at a school of foreign languages the meaning you want to attain in life? [Asking a powerful question to encourage the mentee challenge herself as to her professional choices]

Mentee: Not actually. I guess my graduate studies have broadened my mindset. Now I have quite different professional interests; I am looking for further research options, probably scholarships; besides, I want to get some training to become a trainer, and that has happened under the influence of my field-specific courses.

Mentor: So, you are saying your graduate studies and field-specific courses have influenced the way you look at your future vision or brought you closer to your future vision? [Restating to point out the mentee’s perspective change]

Mentee: Yes, certainly.

Mentor: How would you assess your level of “meaning” in your current profession then?

Mentee: 7.

Mentor: And what about “accomplishment”? [Considering all your professional activities including teaching, graduate work and certified courses that are made available in this workplace]. How would you assess your level of “accomplishment” in your current workplace then? [Asking a powerful, hypothetical question to encourage the mentee to look at the bigger picture linking all aspects of her professional activities]

Mentee: I can say it is 7. Around 5 years ago, I would probably say 5. But now, with all the work I have done, I have come to realize what I needed to improve, and if I can get more study, research or practice opportunities, I will feel that I have accomplished more. Even now, through some friends working at a private high school, I am invited to train the staff about my fields of study. This is going to be a really nice experience.

Obviously, as revealed with the help of restatements and powerful, hypothetical questions, my mentee was developing new perspectives into her career and being gradually equipped with new qualifications, she was trying to accommodate her new interests in her current workplace and professional options, which could provide important insights for the directors and program coordinators at schools of foreign languages with respect to providing new opportunities for such staff.

Finally, as we wrapped up our session, in an effort to link our discussion back to our mentor-mentee experience, I wanted to motivate her to reflect on that relationship as illustrated in Extract 6 below.

Extract 6: Reflecting on mentor-mentee experience

Mentor: What if you wanted to become a mentor one day, as you want to get a teacher training course? What qualities would you like to have? [Asking powerful, what if questions to encourage creative thinking, to visualize a future-self, and allow reverse/relational mentoring to get feedback on the mentor’s work]

Mentee: Just like you. Knowledgeable, having a desire to learn and research, capable of looking at things from different, multiple perspectives, thinking fast in practical ways, good at human relations, providing effective feedback, guiding efficiently, having insights as to potential results, and having good intentions.

Mentor: Wow, these are great! And would you like to hear my feedback on the process? [Giving positive feedback by focusing on the behavior, not the outcomes only, to make the mentee feel good about herself and point out the positive elements as well as creating space for self-reflection as the mentor]

Mentee: [smiling]

Mentor: I wanted to provide you with the opportunity to experience trial-and-error. Sometimes we proceeded at your pace, I gave you the chance to make decisions; you would struggle but at the same time keep brainstorming about the research, you wouldn’t be able to write up the thing in the perfect form in the very beginning, but you would have to experience that.

Mentee: Yeah, you did not spoonfeed.

Mentor: I wanted you to see that it is a cycle and there are many steps interwoven, but when you were drifting off, I would guide you to focus back on the main thing. I wouldn’t have been able to experience all this as a mentor if I had worked with a class of 20 students; I could only get this by working with you individually. [Complimenting]

Mentee: [smiling]

Mentor: As we got closer to the end, you started to see the connections better and with the know-how you have built, you could even help your colleagues with their studies, and I am very happy observing you go through all these and transform in important ways. [Complimenting to show appreciation of the progress]

Mentee: Yeah, it is all with your help. Without your support, I wouldn’t have achieved it.

Mentor: You’re welcome. For me the greatest gift is seeing you touch other people’s lives as well; for instance, when you train the teachers at that private high school, you will be transmitting the meaning we have formed together and that will be the happiest thing. [Celebrating the moment to help the mentee persist and try new alternatives]

Because of mutual reflection, I was glad to see how productive and eye-opening this mentor-mentee experience proved for both of us in that my mentee achieved significant academic and personal gains and I learned how to guide such a reflective learning process as producing graduate work.

Conclusion

Mentoring sessions built on trust remind me of the values embodied in my former teachers; these professionals valued individuals with positive regard and had a love for teaching and desire to develop future generations. Education is a labor-intensive field as it takes on the ambitious role of facilitating the learning process and transferring whatever has been accumulated as products of a collective mind. Reflecting back on her experience as an interpreter for Turkish people at hospitals, prisons and even psychiatric facilities in Britain, one of my mentee colleagues at my current institution in Turkey once said “When they don’t know the language, they are all like as if they were in jail and you feel sorry about their situation, and therefore you want to help them, you want to be useful. In the same vein, I like teaching for this reason; I feel that I am being useful for people; I can help them and I have a mission here, and I internalize this feeling and perception and that keeps me going. I am always energetic during my lessons regardless. I also have ups and downs, my depression and stress, but I always enter the class with a happy face and keep that energy up all the while.” As it is always the case, facts and fads vanish in time, but virtues do remain and this is what we focus on in mentoring: our strategies and tools evolve around such human substance.

My mentee’s ratings and reflections for the five components of professional well-being, embedded in our discussion, following my introduction of the concept to her briefly at the very beginning, offer important implications for successful educational organizations. In order to achieve positive emotions in a workplace, the staff members need to be allowed space, time and energy for their autonomous professional and personal development efforts as well as for rest and refreshment. In addition, efficient means and channels of communication need to be established that promote professional share-and-care, as in well-planned face-to-face meetings or online communication. Productive and meaningful engagement in the workplace requires planning program and instruction activites with a consideration of what people enjoy doing and care about most and what help them find meaning and a sense of accomplishment in their work, as suggested in the previous literature (Ryff, 1989; Shah & Marks, 2004; Pollard & Lee, 2003).

Following the same lead, in mentor-mentee relationships, it has been revealed that it is important to build trust especially when confidentiality issues might arise, keep a non-judgmental, optimistic stance; ask questions that help mentees visualize their aims in a clearer way; and be aware of the importance of being “you” as all mentors approach mentoring in their unique ways.

Acknowledgement

This article was written during my maternity leave and working on it had a refreshing effect. I would like to thank my husband, Suat, and my daughter, Ece for their wholehearted support. This work was supported by the Scientific Research Fund (BAP) at Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University, Turkey, as part of Project 3934 in the 2017-2018 academic year.

Notes on the Contributor

Hatice Karaaslan, holding a Ph.D. in Cognitive Science from the Middle East Technical University, works as an EFL instructor and a Learning Advisor at Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University School of Foreign Languages, Turkey. Her interests include corpus linguistics, critical thinking, advising in language learning and blended/flipped learning. hkaraaslan@ybu.edu.tr

References

Fredrickson B. L., & Branigan C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought‐action repertoires. Cognition & Emotion, 19(3), 313–332. doi: 10.1080/02699930441000238

Kato, S. (2012). Professional development for learning advisors: Facilitating the intentional reflective dialogue. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(1), 74-92. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/march12/kato/

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2015). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

MacDonald, E. (2019). Reflection through dialogue: Conducting a mentoring session with a juku colleague using the ‘Wheel of Reflection’ tool. Relay Journal, 2(1), 45-59.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourishing: A new understanding of the nature of happiness and well-being. (C. P. Lopes, Trad.). Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Objetiva.

Shahi H., & Marks, N. (2004). A well-being manifesto for a flourishing society. Journal of Public Mental Health, 3(4), 9-15. doi: 10.1108/17465729200400023

Pollard, E. L., & Lee, P. D. (2003). Child well-being: A systematic review of the literature. Social Indicators Research, 61(1), 59-78. doi: 10.1023/A:1021284215801

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069-1081. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Yamashita, H., & Mynard, J. (2015). Dialogue and advising in self-access learning: Introduction to the special issue. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 6(1), 1-12.

Dear Hatice,

Though the scope of your article is indeed made clear in the abstract, given the number of intertwining elements, I confess I was only able to grasp the full meaning after reading through it. Which, given the engaging nature of the piece, is not necessarily a bad thing.

The alternation of background information, both of personal and theoretical nature, and structured yet spontaneous dialogue made for a deeply insightful reading experience.

I had no prior knowledge of the PERMA model, and was delighted at how it captures and neatly organises what do truly appear to be a number of core tenets for ones well-being. I found myself pondering over my own psychological stance: it is always useful to have access to a framework that simplifies the complex workings of the mind. Furthermore, what a wonderful tool when engaging others! So, excellent for both self-reflection and purposeful interaction.

I also thoroughly believe in the tenets underlying transformational learning and believe every situational encounter has the potential to reciprocally enrichen our life experience and well-being.

You prove this approach can be effective in one-to-one situations (either teacher/student or teacher/teacher) now I’d be interested in knowing what your thoughts are upon the applicability to a peer-group situation i.e. a group of teachers engaged in discussion?

Also, there would appear to be a certain degree of interpretation on your behalf regarding the mentees answers to your questions. How can you be sure your interpretation truly captures the mentees thoughts?

Furthermore, there could also be issues regarding authenticity: your respective roles may well affect what is being said. When we counsel our students who take part in a course with autonomous learning at its core, one of the requirements is for them to reflect gradually and consistently upon both their thoughts and feelings regarding any course-related activity. The journal is intended as a tool for metacognitive and metaemotional engagement, a way of tracking one’s progress and motivation. I believe spur-of-the moment reflection gets a little closer to the authenticity of what a student is experiencing than a one-on-one interview/counselling session. The two together reinforce this even further. I believe there was no mention of reflection journals/diaries in your piece, so I’d like to know what your thoughts are on issues of interpretation authenticity and also ethicality.

That said, I found the whole story truly inspirational: you certainly practice what you preach, and though the tone and interaction may follow the principles of Intentional Reflective Dialogue, and use the PERMA model as an underlying framework, the way you write is both spontaneous and deeply personal.

Looking forward to reading your response to this brief review.

Dear Sandro,

It is my pleasure to engage in this further reflection, facilitated by your amazing review. Thank you very much for your time and consideration.

I hope this piece, the tone and interaction following the principles of Intentional Reflective Dialogue (IRD) and using the PERMA model as an underlying framework, but the way it is written being both spontaneous and deeply personal, illustrates the column (Reflective Practice) objectives. As such, the story, the meaning, is aimed to unfold as one reads further through the multiple-layers and elements. To be honest, at times I had a hard time bringing all those details around a common story-line, and I am very glad you have enjoyed reading it as that entails it has a composition of some sort.

And similar to you, I was amazed when I first learned about the PERMA model by Seligman through Jo and Satoko during our training, as part of Course 4 coverage. It is definitely a very practical tool stimulating an in-depth discussion of one’s well-being with reference to Positive emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment. These could be investigated while examining individuals’ well-being in any community, excellent for both self-reflection and purposeful interaction, like you are saying.

Therefore, again I believe the tool would prove applicable in a focus-group discussion as well, with some reservation though as to its efficiency if we are expecting better results than a SWOT analysis would return. That’s why, I would say integrating the principles of IRD becomes very critical while utilizing this tool, as part of a Teacher Appraisal program, for instance, that allows research to go where it leads and take us where it goes, acknowledging participant agency.

Adopting such a perspective indeed, I can never be sure if my interpretation, relying on my experience, observation, insight and intuition, truly captures what my mentee had in mind or her authentic experience and/or reflection; still, I received her consent and requested her honest opinion about my interpretation afterwards to achieve some amount of authenticity and ethicality. Considering there will most probably be power issues at play regardless of whether my mentee finds me physically present in a one-on-one mentoring session or mentally present in a journal/diary writing situation, I believe as a researcher mentor, our mentor-mentee experience is mostly based on to what extent our research is conducted in a trusting professional environment with peers working collaboratively toward a common goal, having a vested interest in improving our learning and community.

Accordingly, our transformative learning experience could at best be described in non-measurable ways lacking linearity or some simple categorization, but evolving and attaining new forms together.

Thank you

Hatice-