Ewen MacDonald, Kanda University of International Studies

Nicholas Thompson, Kanda University of International Studies

MacDonald, E., & Thompson, N. (2019). The adaptation of a linguistic risk-taking passport initiative: A summary of a research project in progress. Relay Journal, 2(2), 415-436. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020216

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

This article outlines the rationale, background and preliminary findings of an ongoing linguistic risk-taking passport initiative at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) in Japan. The aim of the initiative is to encourage students to take various risks to build their confidence during their language learning journeys and help them to effectively utilise extra opportunities available for second language learning both inside and outside of the language classroom. The level, nature and frequency of linguistic risks taken, as well as students’ anxiety and confidence levels, willingness to communicate and their strategies for managing emotions are currently under investigation. Initial findings of the initiative indicated that many students felt comfortable and confident using English and taking risks, enjoyed the risk-taking process, and were able to discover new opportunities for practicing English, particularly those available in KUIS’s Self-Access Learning Center.

Keywords: linguistic risk-taking, Japanese university, learner autonomy, self-access learning, willingness to communicate, foreign language anxiety, self-directed learning

Linguistic Risk-Taking

In a second language (L2) learning context, some students hesitate to take linguistic risks, defined by Slavkov and Séror (2019) as “authentic everyday communicative acts that take place outside of the language classroom and involve spontaneous and meaningful second language use” (p. 259). This is often caused by a variety of language anxiety-inducing factors such as negative perceptions of one’s self-proficiency in the L2, fear of embarrassing oneself or being judged, not being able to express oneself coherently, misunderstanding someone or being misunderstood, and feeling uncomfortable adopting a different identity (MacIntyre, 2017). This may in turn result in learners staying within their comfort zones when using the L2, preventing them from participating actively in the classroom and effectively utilising additional opportunities available for authentic L2 communication and engagement inside and outside of the classroom. As learners may avoid these risk-taking opportunities due to their anxiety, they may therefore require interventions that challenge their negative thoughts to help them engage in the opportunities available to them.

The Linguistic Risk-Taking Passport Initiative

The Linguistic Risk-Taking Passport Initiative was conceived and launched by the University of Ottawa (2018) and adapted by partner institutions worldwide, including Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) in Japan. The initiative utilises a research tool called the Linguistic Risk-Taking Passport (Slavkov & Séror, 2019), a small booklet which contains various risks that represent authentic activities for meaningful language practice inside and outside of the language classroom. It is designed to build students’ competence and confidence during their foreign language learning journeys, while helping them discover authentic ways to practice using English or other foreign languages in their daily lives on campus as well as off-campus. The passport is an autonomous tool as learners are given a high degree of control over the risks they choose to take and feel appropriate for their comfort and proficiency levels. In KUIS’s adaptation of the initiative (KUIS Self-Access Learning Center, 2019), a further aim is to guide students in using the university’s Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) as a real-life language learning resource.

At KUIS, passports were available to pick up at the SALC counter, and were also explained by teachers and handed out in some classes. The cover resembles a travel passport (see Figure 1) with learners entering their personal details on the second page.

Figure 1. Risk Passport cover page.

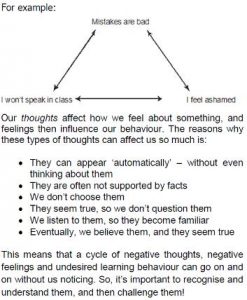

The passport contains information pages that welcome students to the linguistic risk-taking initiative, explain how to use the passport in both English and Japanese (see Figure 2) and provide a straightforward explanation of the rationale behind linguistic risk-taking based on CBT (see Figure 3).

Figure 2. Passport explanation pages.

Figure 3. Linguistic risk-taking rationale pages (adapted from Stallard, 2002).

Over the course of a semester, learners are encouraged to complete as many of the linguistic risks as possible, based on their own personal preferences and how they wish to challenge themselves. Risks can be completed in any order, can be repeated multiple times, and students can choose which risks they try. Learners are also free to propose any additional risks of their own on blank pages in the passport.

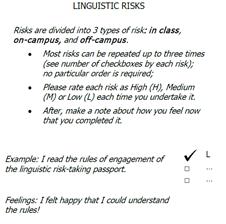

After learners have completed a risk, they give themselves a check mark in the corresponding box for the risk. Learners are asked to indicate whether they perceived the level of the risks to be high, medium or low, by adding the corresponding letter (H, M, or L) beside the checkboxes (see Figure 4). They can also make notes about how they felt after having completed the risks. Risks are divided into three types; in class, on campus and off campus (see Figure 5).

Figure 4. Sample linguistic risks page.

Figure 5. Linguistic risk pages.

After completing at least 20 risks, students are encouraged to complete self-evaluation pages at the back of the passport, responding to questions about the usefulness of the tool and the effect that the risk-taking experience had on their speaking. They can then submit their passport in a box at the KUIS SALC counter to enter a draw for prizes.

Literature Review

As outlined in Slavkov & Séror (2019), a large number of theoretical and pedagogical concepts are relevant to the design of the linguistic risk-taking initiative. Those of particular importance to the KUIS initiative and the research questions outlined in this paper will be discussed below.

Language Learner Autonomy

A central idea in the promotion of learner autonomy is to guide learners in developing the capacity to take control and “make decisions about their learning within collaborative and supportive environments” (Benson, 2011, p. 163). One way this can be facilitated is by helping learners gain an awareness of the range of out-of-class resources available for them to self-direct their learning. Benson (2011) states that the effectiveness of resource-based learning depends partly upon “its capacity to provide experiences of collaboration, or at least a sense of the presence and involvement of others in one’s language learning” (p. 142).

A self-access learning center is one kind of resource-based learning provider. The SALC at KUIS contains various resources that offer learning opportunities to suit all students, and provides social spaces for collaboration and interaction with others to help motivate learners and facilitate the development of L2 fluency and confidence. Learning advisors, lecturers and other staff are also available in the SALC to assist and guide students. The linguistic risk-taking initiative at KUIS is a further means of encouraging students to use the SALC as a language-learning resource.

Additionally, the risk-taking passport acts as a means for students to document their own learning by checking off the activities they try, evaluating the risk level of these and noting their feelings. This can assist learners to keep track of their own learning processes, a critical aspect in the development of learner autonomy, by setting aims and visually seeing what they have achieved and the progress they are making (Dam, 2009).

There are, however, several factors that may impede students’ willingness to engage in autonomous learning that the risk-taking passport aims to address.

Willingness to Communicate

A major contribution to the success of L2 learners is their willingness to communicate (WTC), which refers to a readiness to engage in the L2 at a particular moment in time (MacIntyre, Dörnyei, Clement, & Noels, 1998). L2 learners’ WTC can be influenced by numerous motivational propensities, contextual factors (e.g. the situation and the interlocutor) and individual learner differences (e.g. personality, perceived L2 proficiency, language anxiety) (MacIntyre, 2007). Research has shown that greater opportunities for contact with the L2, low levels of anxiety, and perceived communicative competence are all factors related to higher levels of WTC (MacIntyre, 2014). When using the risk-taking passport, learners can decide the situations they engage in and the risks they choose to take while rating the perceived level of each risk, but are also encouraged to take as many risks as possible (Slavkov & Séror, 2019). It is hoped that through providing opportunities for authentic L2 communication and the freedom for students to make their own decisions regarding the risks they take, the passport could help students to reach higher levels of WTC.

Foreign Language Anxiety

One of the major factors that is a significant impediment for L2 learners’ WTC is foreign language anxiety (FLA), defined by MacIntyre (1999) as “the worry and negative emotional reaction aroused when learning or using a second language” (p. 27). The FLA phenomenon in the context of KUIS has been described previously; students with FLA are sometimes too embarrassed to speak in English during class, and also find it difficult to take advantage of opportunities to speak outside class in the SALC and off-campus (Curry, 2014). It is hoped that through the provision of incentives such as prizes for completion, encouragement from teachers and peers and promotional materials in the SALC, anxious students will feel increased motivation to actively confront their fears about speaking through use of the passport.

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy

The risk-taking passport also offers an opportunity to expand ongoing research aimed at developing materials and activities based on cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) to aid in reducing FLA. CBT gives anxious language learners a rationale and explanation for their feelings, and provides the means of structuring activities aimed at gaining confidence and reducing anxiety (Stallard, 2002). Setting goals towards alleviating individual anxieties is a necessary part of the CBT process, and the passport provides a selection of ready-made goals, or the ability to set personal goals, suitable to be undertaken as the student builds both emotional resilience and linguistic competence. A student-friendly explanation of the CBT process (adapted from Stallard, 2002) and how risk-taking activities can help to reduce negative thoughts that affect speaking confidence is included in the KUIS version of the passport.

The Institutional Context

This study is being conducted at Kanda University of International Studies, a small private university in Japan that largely specialises in language education, linguistics and international communication studies. All students are required to study English and many students study additional languages. English classes for first and second year students are conducted largely in English and take a communicative and task based approach. Third and fourth year students may or may not take such classes, depending on their major and choice of elective modules. The university also has a large SALC that provides many opportunities and resources for students to study and practice English independently. Sections of the SALC enforce an English-only speaking policy, while in other parts students may speak in any language they wish.

Participant Summary

Among the 30 students who submitted risk-taking passports, one was removed from the analysis due to not completing 20 risks, resulting in a total of 29 participants.

Table 1 shows the breakdown of participants. First year students comprised around 75% of participants, with the remaining students in their second or third year. The majority of students (79%) were either members of the English department, or the International Communication (IC) department who also primarily focus on English. The remaining participants were Spanish or Portuguese majors. While English language classes are a requirement for all first and second year students, the lack of non-English or IC majors could be attributed to a large number of risks in the passport related to the use of English, which may not be other students’ primary focus, or being designed for utilising the SALC, which is a largely English-language environment.

Table 1. Participant Summary.

| Department | |||

| Year | IC | English | IA |

| 1st year (n=22) |

12 | 2 | 8 |

| 2nd year (n=4) |

0 | 4 | 0 |

| 3rd year (n=3) |

0 | 3 | 0 |

| Total (n=29) |

12 | 9 | 8 |

Note. (N=29). IC = International Communication. IA = Ibero American languages (Spanish or Portuguese major)

Methodology

Students were offered the opportunity to complete the linguistic risk-taking passport over a period of six weeks between May and July 2019. This was advertised in the SALC through the use of posters, while some teachers explained the project to students in class and distributed passports to those who were interested. Teachers and advisors played no further role in the completion of the passports, as these were to be completed autonomously by students. Upon completion of at least twenty risks, students were asked to turn in their passports to SALC counter staff and sign a consent form for the data from their passports to be collected and used for analysis.

Data from the submitted passports was then entered into excel spreadsheets with teams of researchers analysing the frequency of risks students took, risk levels assigned as well as comments that students made. In order to understand how participants engaged with the passport, how they felt when taking risks, and to discover how successful the initiative was in achieving the desired aims of the project as outlined in the rationale, the following research questions were formed:

- What risk-taking situations are students most likely to engage in?

- What level of risk do students assign to different types of risks?

- How often do students repeat risks?

- What feelings were expressed by students in relation to taking linguistic risks in

different situations and after completing the passport? - What effect did the linguistic risk-taking passport experience have on

students overall?

For RQ4 and RQ5, instances of responses in relation to common feelings which emerged in the passport analysis were highlighted and coded by members of the research team. The number of instances that each feeling was mentioned for different risk-taking situations (in class, on campus, off campus) were then counted and added to a table.

In addition to the above, students who participated and submitted their passports were contacted by email and asked if they would like to volunteer to participate in follow-up structured interviews in order to gather qualitative data. The analysis of interview data is currently ongoing.

Findings

RQ1. What risk-taking situations are students most likely to engage in?

A total of 1,109 risks were attempted by participants. The average number of risks taken was 39, notably higher than the minimum 20 risks students were required to complete, while 82 risks was the highest number attempted.

Table 2 shows both the situations and the interlocutors with which the students engaged in risk-taking. The term “Non-specific” interlocutor denotes that the risk does not specifically state a particular interlocutor. For example, “I made myself say something in English even though I was worried” is an in class risk but does not indicate whether the participant is speaking with a peer or the instructor. This is in contrast to “I asked the teacher for help when I didn’t understand something” which specifically indicates the interlocutor.

The most common type of risk students engaged in were with peers or friends in the classroom. Students were also more likely to take risks on campus with their peers or friends and with non-specific interlocutors, but some also took risks with strangers, teachers and learning advisors. Off campus, students were most likely to take risks with non-specific interlocutors, and more likely to take risks with peers or friends than with strangers.

Table 2. Types of risks taken.

| Interlocutor | ||||

| Type of Risk | Peer or Friend | Non-specific | Teacher or LA | Stranger |

| In class (n=525) |

309 | 150 | 66 | — |

| On Campus (n=312) |

97 | 101 | 49 | 65 |

| Off Campus (n=272) |

52 | 185 | — | 35 |

| Total risks (n=1109) |

458 | 436 | 115 | 100 |

Note. LA = Learning Advisor

In class risks were composed entirely of English speaking activities including discussion participation, requesting and providing assistance and asking and answering questions. The tasks specified speaking to peers, the teacher, in front of the whole class while some did not specify the interlocutor. The three most pursued tasks were as follows:

Q3. I gave my opinion in front of the whole class (n=47)

Q5. I said something in English even though I wasn’t sure of the grammar (n=37)

Q8. I asked a classmate a question in a discussion (n=36)

No obvious pattern could be discerned as to the type of activity participants were more likely to engage in due to the small number of responses and the small number of some task types. It could be hypothesised that risks students took may correlate most with those tasks they had the greatest opportunity to attempt on a regular basis in class.

On campus tasks consisted of taking part in various language activities in the SALC, including conversations with learning advisors, teachers, peers and other English speakers. The three most frequently attempted tasks were as follows:

Q19 I went to the yellow sofa with a friend (n=24) (The yellow sofa is an area for practicing speaking English in a casual way with teachers and other students)

Q25 I made small talk at the SALC counter (n=24)

Q28 I had an appointment with a learning advisor (n=19)

The most frequent tasks were all different in terms of task type and interlocutor. Although no obvious pattern or relationship could be determined, it was noticed that several students mentioned their enjoyment in speaking English at the yellow sofa or with advisors.

Off campus tasks consisted of a mixture of reading and listening tasks, communicating via digital means such as through social media or messaging apps, and speaking to friends, peers or strangers. The four most attempted tasks were as follows:

Q44 I read something in English (news story, website, comic, book) (n=36)

Q42 I watched a movie in English with English subtitles (n=28)

Q41 I watched a movie in English with Japanese subtitles (n=27)

Q40 I watched a movie in English (n=26)

There was a clear preference in this case for tasks that could be completed alone. One exception was using English with customers in a part time job which had a fairly high number of attempts (n=19). When investigating a connection with affect, many students stated receptive activities, such as watching films or reading, to be interesting or fun. As with in class tasks, it could be hypothesised that a main factor influencing selection of tasks was opportunity.

RQ2. What level of risk do students assign to different types of risks?

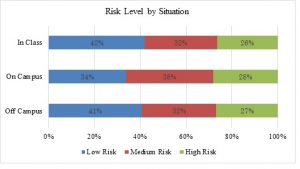

Among the total number of risks taken, participants rated the level of risk around 78% of the time (n=869). As can be seen in Table 3, students were more likely to label activities as low risk, followed by medium and high risk respectively.

Table 3. Risk levels assigned by students.

| Low | Medium | High | |

| In Class (n=419) | 176 | 132 | 111 |

| On Campus (n=234) | 79 | 89 | 66 |

| Off Campus (n=216) | 88 | 70 | 58 |

| Total (n=869) | 343 | 291 | 235 |

Figure 6 shows that in class risks were more likely to be recorded as low risk when compared to risks taken on campus and off campus, potentially due to the familiarity with peers and the classroom environment. Proportionally, on campus risks were seen as a higher risk than any other situation, which could be attributed to students taking risks with unfamiliar interlocutors or utilising SALC resources for the first time. Off campus risks were recorded as marginally more risky than in class risks.

Figure 6. Risk levels by situation.

RQ3. How often do students repeat risks?

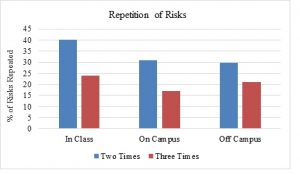

As shown in Figure 7, risks taken in class were most frequently repeated a second time (40%) and were also the most common risks repeated a third time (24%).

Figure 7. Repetition of risks.

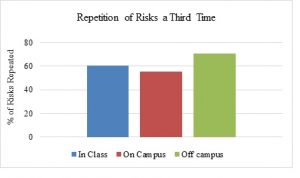

Figure 8 shows that more than half of students who repeated risks a second time took the same risks for a third time. This was especially notable for risks taken off campus, with 70% of students who took a risk twice taking the same risk for a third time.

Figure 8. Repetition of risks a third time after second attempt.

RQ4. What feelings are expressed by students in relation to taking linguistic risks in different situations and after completing the passport?

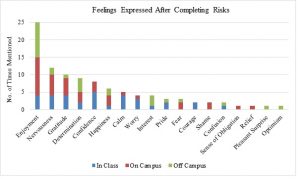

17 of 29 participants commented in the passport on how they felt after completing different risks. The results are presented in Figure 9 based on the number of times each feeling was mentioned.

Among those who made comments, students predominantly indicated positive feelings after taking risks. While several participants did experience anxiety, some were able to overcome their feelings at the time of taking the risk, or expressed their determination to continue risk-taking to practice English. Some of the main feelings with quotations from students are presented below the chart.

Figure 9. Feelings expressed after completing risks.

Enjoyment

A sense of enjoyment when taking risks was mentioned 25 times, which was the most frequent feeling expressed overall, and also for risks taken on campus and off campus. In class, students indicated their enjoyment in talking with their classmates or friends.

S25: “Speaking English with friends was really fun.”

Several students commented on enjoying communicating with learning advisors, teachers, language practice partners (LPPs) and other students on campus while utilising SALC resources and participating in events and workshops.

S6: “I made a friend who is LPP. I have talked with her three times and I really enjoyed.”

S15: “SALC events are very fun! Wafuku day and afternoon tea time is good!”

S11: “I went to the yellow sofa with my friend so I really enjoyed talking. In addition, I didn’t know the teacher, but I enjoyed communicating with her.”

Off campus, some students mentioned their enjoyment in using English to talk with foreign friends and on social media, in addition to using movies as a tool for learning English.

S8: “I have chatted with my friend who is from America. Fun!”

S5: “Watching a movie in English …is a fun way of studying English I think.”

Confidence

An increase in confidence was mentioned eight times, and was the most common feeling expressed for risks taken in class. Getting used to speaking in front of others and positively overcoming a fear of making mistakes were described.

S5: “Asking a classmate a question was hard at first, but I’m getting used to doing it little by little.”

S6: “Don’t be shy! It’s my feeling. If it is not correct my grammar, most everyone understand my English.”

Gratitude

Gratitude towards the kindness of their teachers and peers in class and on campus was mentioned ten times, in particular for assisting them with their English and helping them feel relaxed.

S20: “My teacher and classmates always help me when I don’t know how I can say in English. I want to say ‘thank you’ to them.”

S14: “When I talked with native speaker, I didn’t feel any stress even though I’m not perfect English speaker. I want to appreciate teachers to help me a lot.”

Nervousness

Nervousness was expressed by students twelve times. This was often when taking risks on campus that involved talking with new people, while others felt nervous speaking in front of their peers in class.

S11: “I felt a little nervous when I talk to teacher or people whom I don’t know, so I couldn’t go to yellow sofa alone, but with friends.”

S25: “I was nervous when I said opinion in front of the whole class.”

At the same time, several students were able to overcome their nerves when they felt comfortable with the interlocutor or the environment.

S11: “I feel a little nervous, but I was not afraid to say answer because atmosphere and environment were very familiar to me.”

S20: “I was very nervous before talking with teachers, but I had a good time thanks to them.”

S5: “I was so nervous at first, but I enjoyed talking with LPP.”

Worry, Fear and Shame

Feelings of worry, fear or shame were noted nine times, typically when students tried a new risk for the first time or due to students’ anxiety about their English proficiency.

S14: “I felt not good cause all other students who have joined TED are good at speaking English. I could not tell them my opinion clearly.”

S11: “I was afraid to encourage my friends to speak English on the second floor.”

S11: “When I talk to classmate who is very good at English, I was very nervous. I was worried about fluency of my speaking.”

Some of these students were able to succeed in dealing with their initial negative feelings when they experienced success in their risk-taking situation.

S13: “I was super upset when foreigners came to my part-time job, and they could only speak English. My hands literally shook. However, I could explain using English and body language. I’m proud of myself.”

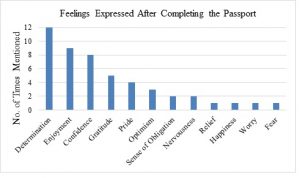

21 participants gave final remarks on the back page on the passport in relation to the effect that the linguistic risk-taking passport experience had on their English speaking. It can be seen in Figure 10 that determination, enjoyment and confidence were the most commonly described feelings. Student comments in relation to some of the feelings that emerged are discussed below the chart.

Figure 10. Feelings expressed after completing the passport.

Determination

A sense of determination was mentioned by 12 students, which was the most frequent feeling described upon completing the passport. Students generally expressed a desire to continue taking risks in the future through engaging in opportunities to communicate in English in daily life and by utilising resources available in the SALC. The risk-taking passport also assisted some students in recognising learning opportunities they could take.

S15: “I have never done many things in SALC so I want to try them. I want to improve my English skill! Therefore, I will try to use English more than now. If I have free time, I will go to yellow sofa. I have never been to learning help desk, SALC workshop and so on. I want to go there so I will go with friends. To talk in English is important, so I will keep trying that.”

S12: “There were many chances to use English in daily life I could find. I think it was the best thing in this project. So, I will use English more than before that.

Several students also realised the importance to persevere and take linguistic risks even when faced with difficulties or concern about their language ability.

S8: “Even if I can’t remember words or phrases, it is important to try saying, I thought.”

S13: “My English is of course not perfect, but the most important thing is whether I try to practice speaking English or not. This passport experience made me realise that. I will keep practicing hard to speak English from now on.”

Some students’ motivation was also positively affected by the passport which further strengthened their resolve to challenge themselves.

S20: “Thanks to this activity, I was able to see what I could achieve and was motivated to try my challenges. I will keep doing challenges after this activity is over.”

S11: “I think this experience affect my motivation to learn speaking because I thought ‘Why am I afraid to speak English when I do such tasks?’ …Therefore, I’d like to try things that I like doing because I want to improve my speaking while having fun.”

Confidence

Eight students commented that the passport helped grow their confidence in using English.

S22: “During this challenge, I could get a little bit confident. I was glad to do this challenge.”

S10: “I can speak and talk English more easily than I used to. I have come to feel it is not difficult to use English.”

Learning new ways to use English outside of class through the passport also contributed to some students’ confidence gain.

S21: “I thought I become confident in using English. I had no idea how to use English outside of class, but I was helped by this passport.”

Pride

Four students expressed a sense of pride for challenging themselves to use English more through using the passport.

S2: “In this time, I tried to use English more times than usually. Eventually, I can get proud of my English a little bit.”

S5: “If I didn’t try doing this passport, I wouldn’t feel such a sense of achievement.”

Optimism

Three students also expressed optimism that their speaking ability would continue to improve if they kept challenging themselves and taking opportunities available to them.

S11: “If I can overcome risks, my speaking will improve.”

S24: “I think I can make good opportunity at yellow sofa. It can be good conversation at there.”

RQ5. What effect did the risk-taking passport experience have on students overall?

15 of the 29 students who submitted their passports completed a multi-choice questionnaire contained inside the back cover of the passport. Table 3 shows that the majority of these students had positive perceptions regarding the experience on their comfort level and confidence in using English, communicating with others outside the classroom and taking risks. Additionally, all students agreed that the experience inspired them to use English more often. Just over two thirds of participants also agreed that the passport helped them discover new opportunities for using English.

Table 3. The overall effect of the risk-taking passport experience on students.

| Strongly

Agree |

Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly

Disagree |

|

| 1. I am more comfortable speaking English with strangers | 2 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| 2. I am more comfortable speaking English with people I know | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 3. I am more comfortable taking risks in English | 2 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| 4. I am more likely to communicate in English outside the classroom | 3 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 5. I am inspired to use English more often | 7 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6. My confidence in English has improved | 4 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 7. This passport has helped me discover new opportunities for practicing English | 7 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

Discussion

Although only a small number of students have completed the risk-taking passport so far, there are a few notable findings. In particular, among those participants who indicated their feelings about risk-taking and their overall experience, responses were strongly positive in terms of enjoyment, determination and a growth in confidence, indicating a promising influence on student affect with regard to autonomous participation in linguistic risk taking. This relates to concepts discussed in the literature review: willingness to communicate in an L2 is positively influenced by a reduction in foreign language anxiety, greater motivation, and an increase in confidence regarding perceived L2 ability (MacIntyre, 2007). In this way, the passport can be seen as a success for those students who used and completed them. While some students described feelings of nervousness when taking risks, they were able to overcome their anxiety in most cases, and expressed determination and enjoyment upon completion of the passport. Additionally, comments from several students indicated that the passport helped them become more aware of the variety of language learning opportunities and resources available to them in their university life, particularly in the SALC.

With regard to the frequency and types of risks taken, students took twice as many risks on average than they were required to complete, and a large number of these were repeated several times, suggesting many were highly engaged in the risk-taking initiative. Students were more likely to take risks in class, and generally found them to be lower risk than tasks outside the classroom. Little could be found in the data to provide an understanding of why this might be, though some common sense hypotheses can be made. The reason could be attributed to greater opportunity to participate in class activities and familiarity with the setting. Many of the in class risks are likely to be tasks that students are compelled to undertake even without the passports, as English classes at KUIS generally take a communicative approach. This shows how convenience, opportunity and contextual factors strongly shape the choices that students make around which tasks to try.

One uncertainty, however, is the students who did not complete or turn in the passports. Over 500 passports were distributed, yet only 29 were handed in. This potentially raises questions about barriers to entry for the use of risk-taking passports before effective use of them can be made, such as whether more specific goal-setting to alleviate anxiety needs to be made, and what level of autonomy needs to have already been obtained.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations in this pilot study of the risk-taking initiative. Firstly, a small number of students submitted their passports at the deadline. This low take-up rate may have been due to a variety of reasons such as students’ language motivation and pre-existing level of autonomy, or a result of the initiative beginning midway through the semester and ending during a period where students were busy preparing for examinations. Additionally, while the initiative was advertised in the SALC, promotion of the passport by teachers may have varied. Faculty were informed of the project through email and flyers, but it is unknown how many teachers promoted the passport to their classes or how they encouraged students to participate in the initiative.

Additionally, as previously mentioned, not all participants rated the level of risks they took or mentioned their feelings in the passport, completed the multi-choice questionnaire, or gave closing remarks regarding their experience. As a result, the findings that we present in this paper, especially in regard to participants’ feelings, are limited to those who made written comments before submitting their passports.

A possible limitation of the passport itself is that it may be most effective for learners who already have a certain degree of learner autonomy. While one intention of the risk-taking passport is to provide students with opportunities to direct their own learning, particularly through using the SALC as a language-learning resource, Benson (2011) notes that successful resource-based learning is strongly dependent on learner’s autonomy, and may work best for those who already have a high degree of autonomy plus the capacity to engage in self-directed learning. Although questionnaire results show an increase in participants’ comfort and confidence in taking risks, their degree of autonomy and methods of self-directed learning before using the passport is not known.

A second limitation of the passport that was noticed during the analysis is that participants’ interpretation of the term ‘risk’, in particular regarding ‘risk level’, may have varied and influenced how they noted ‘level of risk’. The English description in the passport referred to high, medium and low ‘level of risk’. However, the word ‘difficulty’ was used in the Japanese description due to the word ‘risk’ having a different nuance in Japanese with a more negative connotation. As a result, it is difficult to say whether students based their ‘level of risk’ on the difficulty or riskiness of some tasks. An example that may have been influenced by this is “I read something in English (news story, website, comic, book)”. This was a popular activity and was mostly considered by students as ‘high risk’. However, it would be assumed that reading by oneself generally involves minimal risk, so some students may have indicated the difficulty of the task depending on their individual interpretation.

Future Directions

This paper is based on an initial pilot study of the linguistic risk-taking initiative at KUIS and uses a small sample of data from a low number of respondents. The initiative will be repeated in the following semester and its effects will continue to be investigated into 2020. The research team will examine effective means of promoting the passport with student participation and by potentially using results from the pilot study to show the benefits of involvement to students. Additionally, to solve the problem of students not supplying their final thoughts upon completing the passport, it is intended that SALC staff will check that students have completed the back page of the passport at the time of submission.

Analysis of participant interviews in relation to learners’ anxiety in different situations, their strategies for managing emotions during risk-taking, and how the initiative affected their perceived language self-confidence and willingness to communicate is currently ongoing. In addition, the change in students’ perception of risk level after repeated attempts of the same risk will be investigated.

Notes on the contributors

Ewen MacDonald is a lecturer in the English Language Institute at Kanda University of International Studies where he also completed his MA TESOL degree. His research interests include learner autonomy, teacher cognition, pragmatics and corrective feedback.

Nicholas Thompson is a lecturer in the English Language Institute at Kanda University of International Studies. He completed his MA Applied Linguistics degree at The University of Essex. His research interests include global issues research and individual differences such as motivation, confidence and learner anxiety.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Jacob Mahaffey from Illinois Wesleyan University who inputted the passport data, as well as the research team members who assisted in the completion of the data analysis: Claire Bower, Neil Curry, Bethan Kushida, Phoebe Lyon, PJ Standlee, Anna Twitchell and Heather Yoder. Many thanks also go to the students who participated in the initial trial of the linguistic risk-taking initiative and shared their valuable experiences that will help to inform the research team’s approach going forward.

References

Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching autonomy (2nd ed.). Oxon, UK: Routledge.

Curry, N. (2014). Using CBT with anxious language learners: The potential role of the learning advisor. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(1), 29-41. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/curry.pdf

Dam, L. (2009). The use of logbooks – a tool for developing learner autonomy. In R. Pemberton, S. Toogood, & A. Barfield (Eds.), Maintaining control: Autonomy and language learning (pp. 125-144). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

KUIS Self-Access Learning Center (2019). KUIS Linguistic Risk-Taking Passport Initiative. Retrieved from http://kuis8.com/passport/

MacIntyre, P. D. (1999). Language anxiety: A review of the research for language teachers. In D. J. Young (Ed.), Affect in foreign language and second language learning (pp. 24-45). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

MacIntyre, P. D. (2014). Willingness to communicate. In P. Robinson (Ed.), The Routledge encyclopedia of second language acquisition (pp. 688-691). New York, NY: Routledge.

MacIntyre, P. D. (2017). An overview of language anxiety research and trends in its development. In C. Gkonou, M. Daubney, & J-M. Dewaele (Eds.), New insights into language anxiety: Theory, research and educational implications (pp. 11-30). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

MacIntyre, P. D., Dörnyei, Z., Clement, R., & Noels, K. A. (1998). Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in an L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. The Modern Language Journal, 82(4), 545-562. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb05543.x

Slavkov, N., & Séror, J. (2019). The development of the linguistic risk-taking initiative at the University of Ottawa. Canadian Modern Language Review, 75(3), 254-272. doi:10.3138/cmlr.2018-0202

Stallard, P. (2002). Think good – feel good: A behaviour therapy workbook for children and young people. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

University of Ottawa. (2018). Linguistic Risk-Taking Initiative. Retrieved from https://ccerbal.uottawa.ca/linguistic-risk/

I found the project summary very insightful. Emotions are a key factor when it comes to practising a foreign language: in particular, anxiety may be detrimental to taking initiative and, for instance, using the foreign language with known or unknown people in everyday situations. So, any valid instrument aiming to lower the affective filter should be welcomed and taken into due consideration.

This seems to be the case with the risk-taking passport. Students are encouraged – and somewhat challenged – to take risks, but in a planned way. They can set themselves goals, choosing beforehand which risks they want to take, and they can keep track of the results. In some ways the passport has a similar function as a logbook: you keep record of your progress and, at the end, you have a written proof of what you have achieved. Beside incentives for completion, I think the best reward for students taking risks is an increased confidence in themselves and their ability to deal with different situations and tasks in the foreign language. This actually emerges in the participants’ comments.

It is not clear to me whether after handing in the passport students are contacted to discuss the marked risks and the self-evaluation page with and advisor or a teacher. A 1:1 feedback session may prove to be useful both for the learners, who can reflect on their achievements, and for the advisor/teacher, who could receive from the learners additional and more detailed feedback on their experience. This, of course, is not possible if the passport has to remain strictly anonymous.

The authors write that “[a] possible limitation of the passport itself is that it may be most effective for learners who already have a certain degree of learner autonomy.” This raises a more general question about learner autonomy: should it be trained before proposing the use of instruments that require a minimum of awareness about one’s own degree of autonomy, as it is the case with a logbook or a risk-taking passport? Training self-directed learning before having the students engaged in tasks requiring autonomy may increase the number of passports completed and handed in.

What further attracted my attention was that the English word “risk” was translated into Japanese as “difficulty”, since the literal translation has a negative connotation. I wonder how this may have influenced the way students evaluated their tasks. Perhaps this translation issue should be born into mind when considering and discussing the present and future results.

Finally, it has to be considered that out of 500 distributed passports only 29 students completed the tasks and handed in the passport: the database would probably need to be extended in order to attain statistically more solid results and draw large-scale conclusions. Anyway, I find this is the first step of a very fascinating project: it would be interesting to follow its development in the years to come.

Dear Adriano,

Thank you for your response to our article.

In regards to your question, after handing in the passports, participants could consent to an optional interview. The primary purpose of this interview was to help the research team understand why learners chose/did not choose certain risks and their feelings before, during and after completing the risk-taking passport. However, the kind of questions that were asked also stimulated reflection for the learners on their experience and achievements.

The initiative is being repeated in the current semester and will continue in the following academic year. The research team is also presently looking into different ways to promote the passport. We intend to report further findings on the initiative in the future and anticipate that growth in the amount of data that we obtain will allow us to come to clearer conclusions on the effects that the passport has.