Gordon Myskow, Kanda University of International Studies, MA TESOL Program

Sina Takada, Kanda University of International Studies, Graduate Student

Kazune Aida, Tsuda University, Graduate Student

Myskow, G., Takada, S., & Aida, K. (2020). Blooming autonomy: Reflections on the use of bloom’s taxonomy in a TESOL graduate course. Relay Journal, 3(1), 5-24. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/030102

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a highly influential framework for classifying cognitive processes and developing course objectives. It has been used by curriculum planners and teachers of subject-matter courses such as history and mathematics to ensure that courses address a variety of cognitive abilities. With the growing emphasis on subject-matter instruction in English language education, as evidenced in approaches such as Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) and English-Medium Instruction (EMI), Bloom’s Taxonomy has also become increasingly relevant to language teachers. In this paper, participants in a TESOL graduate course for in-service teachers share their experiences using Bloom’s Taxonomy as a reflective tool for examining educational practices in their contexts. Summaries of reflective diaries are presented and analyzed by course participants for themes among them. Key themes are 1) increased awareness of the over/under emphasis of some cognitive processes in courses, 2) the challenges of incorporating higher-order thinking skills into classes, and 3) the importance of scaffolding higher-order thinking skills. Each of the Taxonomy’s cognitive processes and subprocesses are illustrated in the paper using pedagogical materials developed for a Japanese junior high school EFL textbook reading passage. The authors conclude that Bloom’s Taxonomy can be a valuable resource not just for raising awareness of the extent to which higher or lower-order thinking skills are addressed in courses but for empowering teachers to make informed choices about their course content, thus contributing to greater teacher autonomy.

Keywords: Bloom’s Taxonomy, Higher-order-thinking skills, critical thinking, autonomy, Japanese EFL secondary school context

Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational objectives, developed by Benjamin Bloom (1956) and revised by Anderson and Krathwohl (2001), has been called in some respects “one of the most influential documents in the history of education” (Dalton-Puffer, 2013, p. 221). Yet its impact in the field of second-language learning has been limited. This is perhaps unsurprising as the Taxonomy was designed to classify subject-matter objectives for courses such as math and history rather than ESL/EFL language objectives. Its comprehensive inventory of the various knowledge types (e.g., conceptual, meta-cognitive) and underlying cognitive processes (e.g., Analyze, Create) would be of limited use in traditional language classrooms where the focus is often on memorizing vocabulary and grammar patterns.

However, with the growing influence of such approaches as Content-based Instruction (CBI), Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), and English-Medium Instruction (EMI) that situate subject-matter at the forefront of instruction, Bloom’s Taxonomy has become increasingly relevant to language programs in need of a systematic approach to incorporating a variety of lower and higher-order thinking tasks (e.g., Ball, Kelly & Clegg, 2015). Japan’s Ministry of Education (MEXT) has also recognized the importance of higher-order cognitive skills in English education with its emphasis in the recent Course of Study on deep learning and critical thinking. But of course actually implementing such learning outcomes in Japanese schools is no easy task. As many have observed, the development of higher-order thinking skills is not typically an instructional priority in most English classrooms (e.g., Okada, 2015), and English textbooks tend to focus on lower-level thinking skills such as memorization and comprehension (Minemisha, 2014).

Even if future Ministry-Approved textbooks feature tasks incorporating a range of higher and lower-order cognitive processes, there is no guarantee that they will be implemented in the classroom. As with all curriculum innovation, the critical juncture or ‘point of sale’ is in particular classrooms between individual teachers and their students. Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) acknowledge as much in their introduction to the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy, observing that the Taxonomy’s audience is not just curriculum planners and textbook writers but teachers—as it is they who “determine what takes place in their classrooms through the curriculum they actually deliver to their students and the way in which they deliver it” (p. xxii).

For teachers, Bloom’s Taxonomy also has the potential as a tool for ongoing professional development. As a classification system of knowledge types and cognitive processes, the Taxonomy can be used as a lens for critical analysis of course content and materials, promoting reflective practices and empowering teachers to make informed decisions about the treatment of content in language classes. In other words, Bloom’s Taxonomy has the potential to foster greater teacher autonomy—an essential aspect of teacher expertise, defined by Aoki (2002) as “the capacity, freedom, and/or responsibility to make choices concerning one’s own teaching” (p. 111) (see Smith, 2003 for a useful overview of teacher autonomy).

In this paper, we share our reflections from a TESOL graduate course where we used Bloom’s Taxonomy as a resource for reflection and exploration of our teaching. The paper begins with an overview of the various categories of the Taxonomy in the context of a Japanese secondary school English textbook. Summaries of the reflective diaries kept by each course member are then introduced followed by a discussion of the key themes that emerged among them. The paper begins with an overview of Bloom’s Taxonomy by the course instructor (Gordon).

Overview of Bloom’s Taxonomy

Bloom’s Taxonomy, as outlined in Anderson and Krathwohl (2001), is an elaborate description of the various types of knowledge and cognitive processes that underlie the study of school subject-matter. This paper is concerned with the cognitive process dimension of the taxonomy. The first three cognitive processes (Remember, Understand, Apply) are often referred to by the acronym LOTS (Lower-Order Thinking Skills), and the latter (Analyze, Evaluate and Create) by HOTS, or Higher-Order Thinking Skills. For a variety of reasons, LOTS tends to receive the most focus in schools (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001, p. 30). This is almost certainly the case in traditional language learning classrooms where the focus is often on memorization of vocabulary and grammar–a tendency that is perhaps especially prevalent in Japanese secondary schools where the grammar-translation method (yakudoku) and discrete-point language tests are commonplace.

In this section, a reading passage from a Japanese ministry-approved textbook is used to illustrate activities for each of the Taxonomy’s main cognitive processes and their various sub-processes. The passage (not shown here) is from the textbook Sunshine 2 for second-year junior high school students (2011, pp. 65-69). It is about an impassioned speech to save the environment at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio by a then twelve-year old Canadian female named Severn Cullis-Suzuki. The various activities outlined here do not appear in the textbook. They have been developed by the course instructor to illustrate how a simple reading passage can be used to develop a range of cognitive process objectives, even with younger learners of limited language proficiency. Cognitive processes are color-coded for ease of reference.

Remember

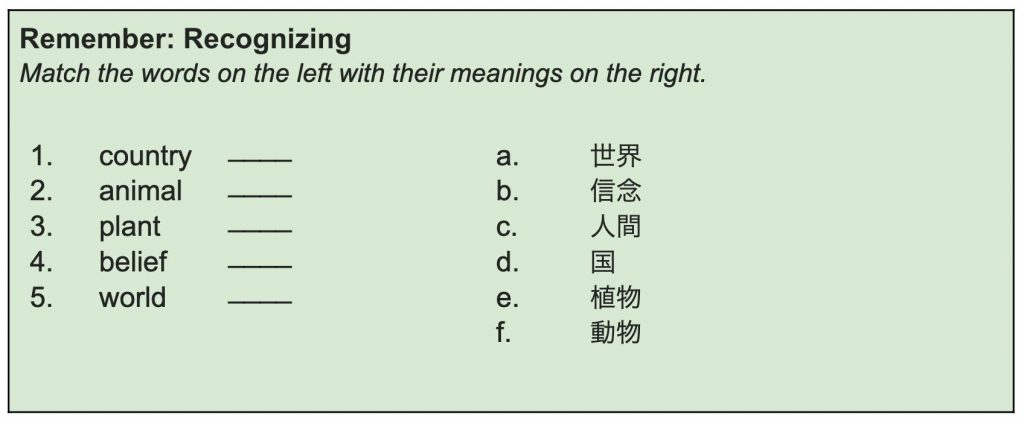

According to Anderson and Krathwohl (2001), Remember is the instructional focus “[w]hen the objective.. is to promote retention of the presented material in much the same way as it was taught…” (p. 66). Two subtypes of Remember are Recognizing and Recalling. Recognizing simply “involves retrieving information from long-term memory in order to compare it with presented information” (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001, p. 69). Figure 1 shows a Recognizing task for assessing recollection of vocabulary items from the target reading passage. As this exercise shows, students are to simply identify the meanings of words they have previously encountered. The definitions of these words listed on the right would be the same as, or very similar to, those presented in class, thus requiring students to simply Recognize previously learned information.

Figure 1. Remember (Recognizing) cognitive process sample activity

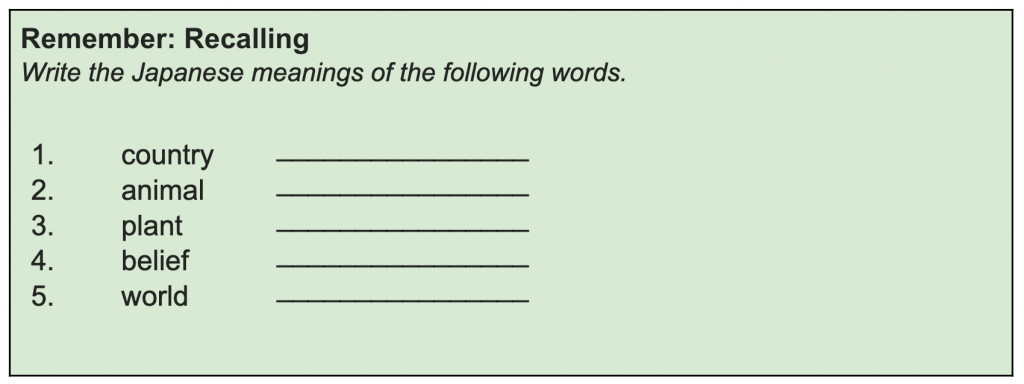

The second subtype, Recalling, requires learners not simply to recognize but “retriev[e] information from long-term memory” (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001, p. 69). Figure 2 shows the same target vocabulary items from Figure 1, but the definitions have been removed, so students will have to Recall rather than just Recognize their meanings.

Figure 2. Remember (Recalling) cognitive process sample activity

Figure 2. Remember (Recalling) cognitive process sample activity

Understand

The second cognitive process in Bloom’s Taxonomy, Understand, involves “construct[ing] meaning from educational messages” (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001, p. 70). In other words, students do not simply memorize new information; they must integrate the new concepts with their existing knowledge. Anderson and Krathwohl (2001, pp.70-76) list seven Understand sub-processes. Each of these are detailed in turn below.

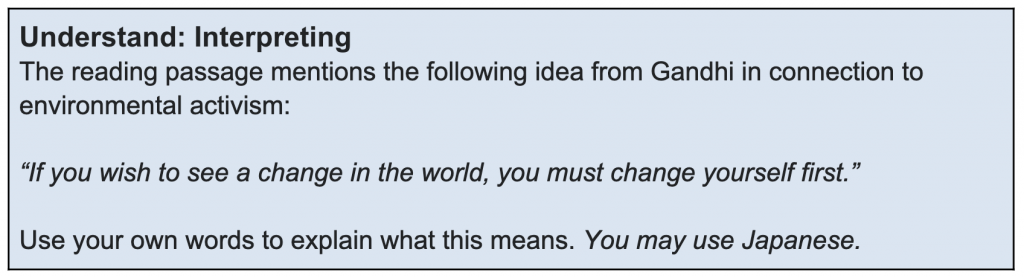

The first subprocess of Understand is Interpret, which requires students to “convert information from one representational form to another” (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001, p. 70). For example, learners could represent the meanings of a reading passage by drawing pictures of events depicted in it. They could also convert words to other words by paraphrasing or translating them into another language. Figure 3 shows a sample Understand (Interpreting) exercise for the passage about Severn Cullis-Suzuki. Students have the option of paraphrasing in their L2 (Use your own words…) or translating into their L1 (You may use Japanese…).

Figure 3. Understand (Interpreting) cognitive process sample activity

Figure 3. Understand (Interpreting) cognitive process sample activity

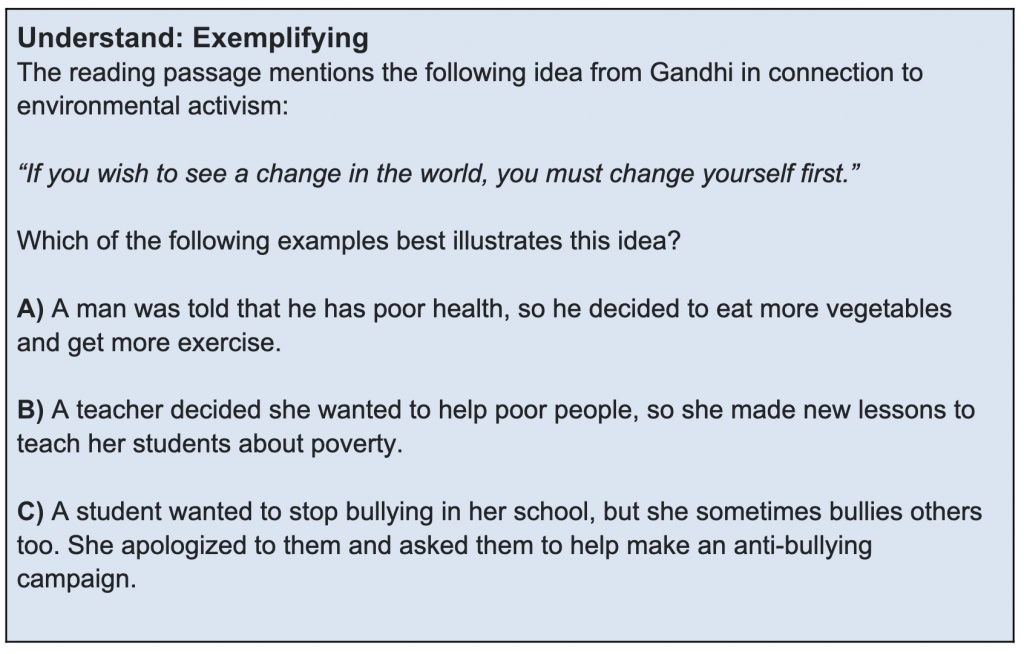

The second subprocess of Understand outlined in Anderson and Krathwohl (2001, pp.71-72) is Exemplifying. This requires students to “select or construct” a specific instance of a general concept. Figure 4 shows a sample Exemplifying task using the same quotation from the previous exercise attributed to Gandhi. Rather than having students construct their own original examples to illustrate the meaning of this quote, they simply select the most appropriate of three options (a-c). For secondary school students of English in Japan, constructing their own examples would likely consume a great deal of class time and place serious demands on their existing language resources. Having learners select from a list of prepared options reduces the learning burden and provides a useful scaffold toward constructing their own examples.

Figure 4. Understand (Exemplifying) cognitive process sample activity

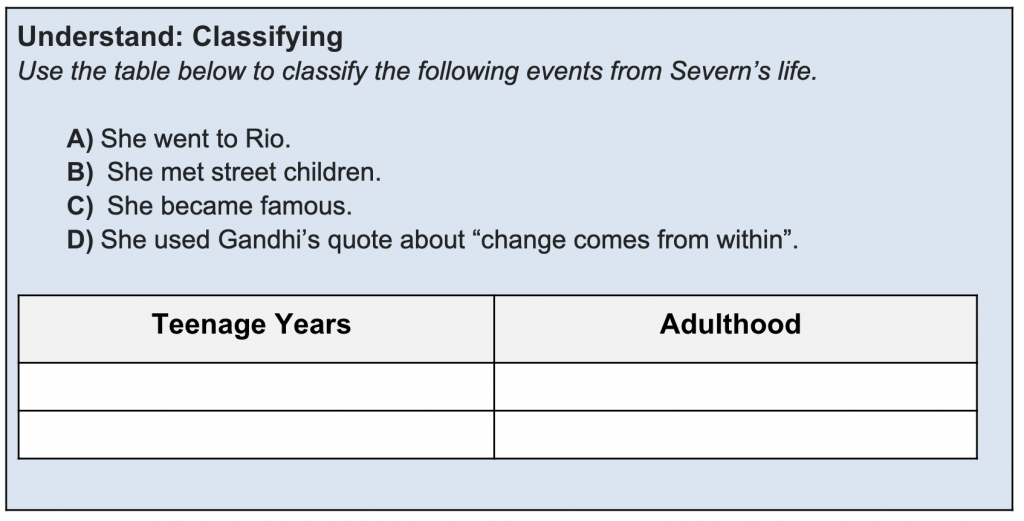

The next subprocess of Understand, Classifying, is the opposite of Exemplifying. While Exemplifying requires students to select particular instances of a general concept, Classifying “occurs when a student recognizes that something (e.g., a particular instance or example) belongs to a certain category (e.g., concept or principle)” (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001, p. 72). In Figure 5, the two categories (Teenage years and Adulthood) are used to classify events in Cullis-Suzuki’s life. As the passage does not present this information along a simple linear timeline, this activity calls for a deeper understanding of the relationship among events.

Figure 5. Understand (Classifying) cognitive process sample activity

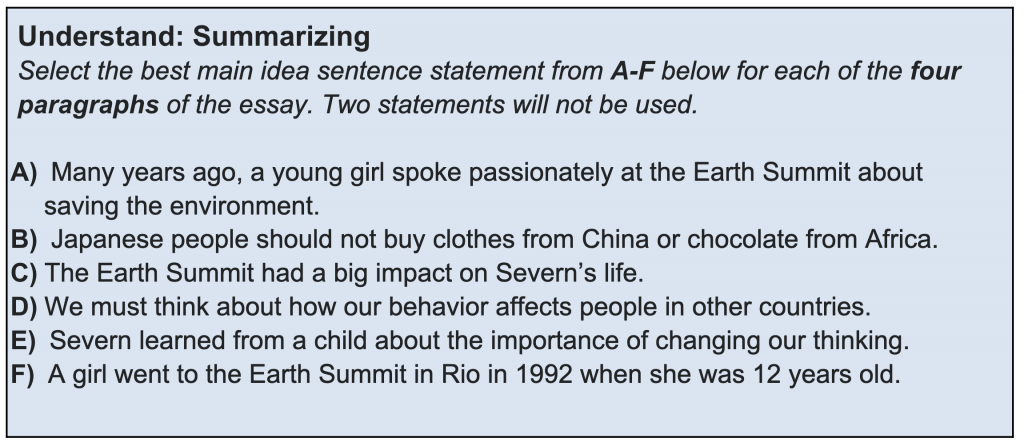

Another Understand subprocess identified in Anderson and Krathwohl (2001, p. 73) is Summarizing. This process involves “a student suggest[ing] a single statement that represents presented information or abstracts a general theme” (p. 73). Figure 6 shows a Summarizing activity that requires learners to select the appropriate statements that best summarize each paragraph of the reading passage (see Myskow et al. 2018, pp. 370-372 for a cooperative variation of this activity called “Scrambled Para-tence”). Like the previous activity, learners are to select from ready-made options–a process that is less demanding than having them construct their own responses.

Figure 6. Understand (Summarizing) cognitive process sample activity

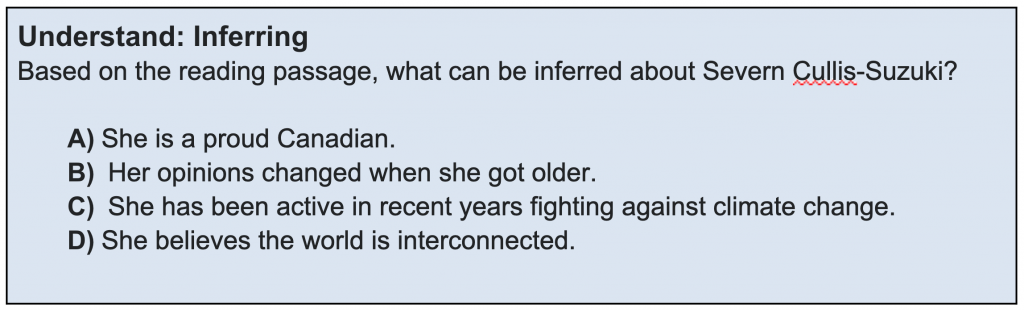

Another way that learners can show that they Understand is by Inferring–a question type that involves “finding a pattern within a series of examples or instances” (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001, p. 73). Figure 7 shows an Inferring task for the passage about Severn Cullis-Suzuki. While all of the options in Figure 7 (A-D) may in fact be true, only Option D is a conclusion that can be drawn based on the information presented in the passage.

Figure 7. Understand (Inferring) cognitive process sample activity

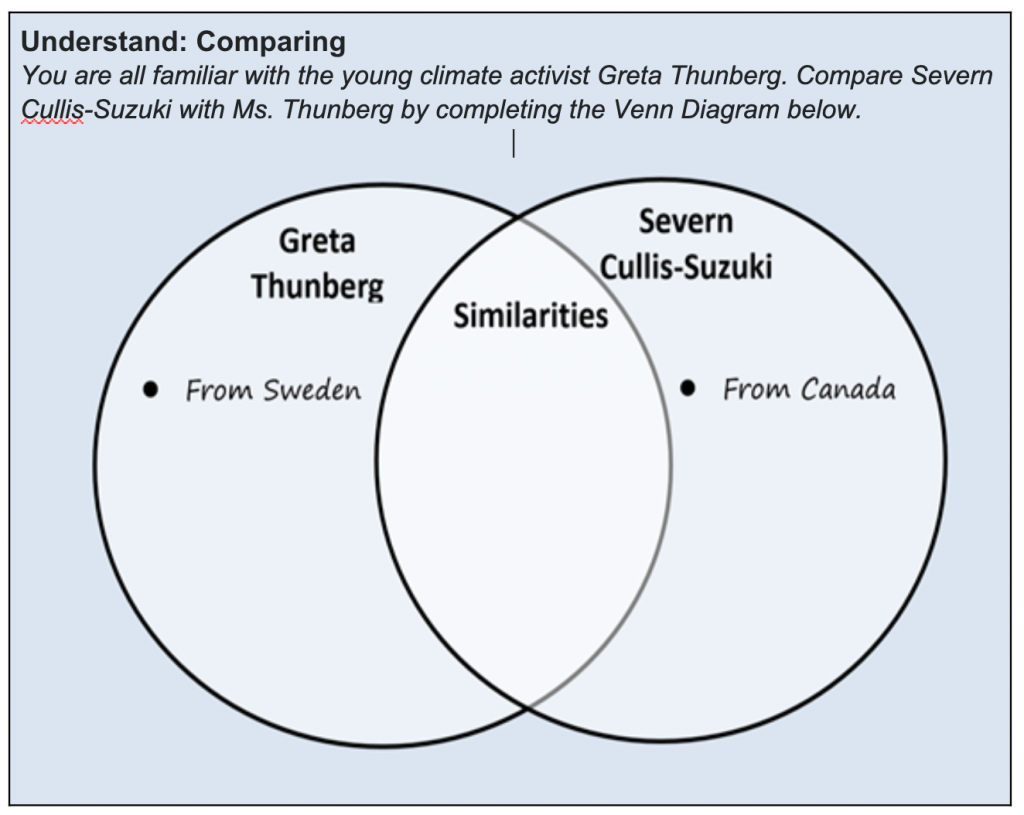

The fifth subprocess of Understand is Comparing, which is described in Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) as “detecting similarities and differences between two or more objects, events, ideas, problems, or situations, such as determining how a well-known event (e.g., a recent political scandal) is like a less familiar event (e.g., a historical scandal)” (p. 75). Figure 8 contains a Venn diagram for comparing and contrasting information about Severn Cullis-Suzuki, the subject of the reading passage, and Greta Thunberg, the young environmental activist who has attracted much attention in recent news. Thus, Cullis-Suzuki, the less familiar ‘historical’ figure that students are learning about, is compared with the more recent and familiar Greta Thunberg. Of course, such comparisons only work if students are actually familiar with the recent figure!

Figure 8. Understand (Comparing) cognitive process sample activity

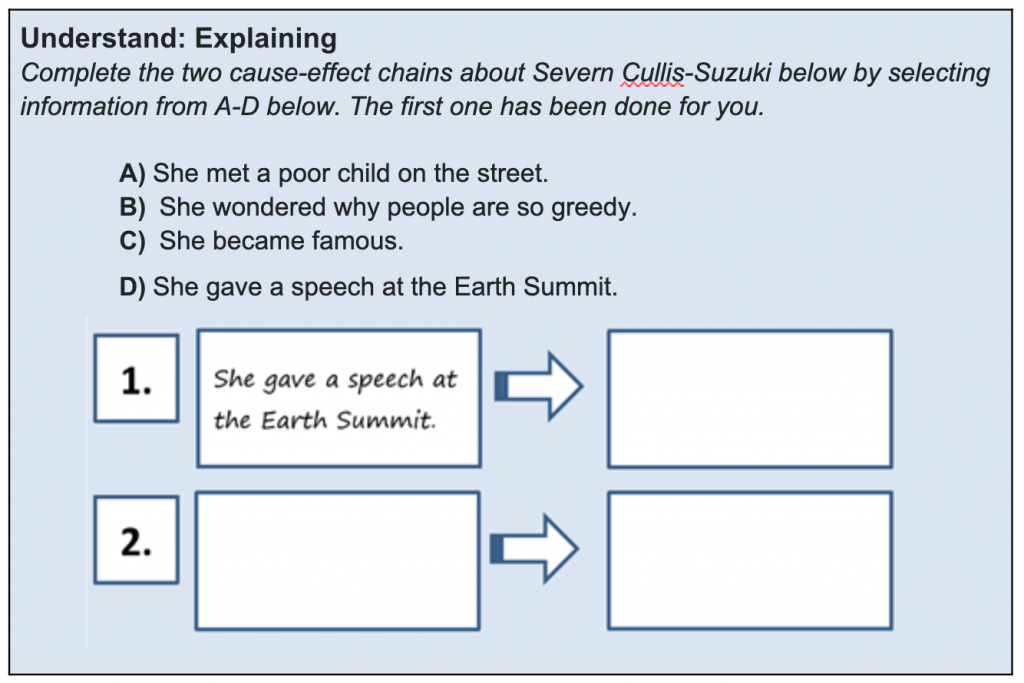

The final cognitive subprocess of Understand, Explaining, “occurs when a student is able to construct and use a cause-and-effect model of a system” (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001, p. 75). Figure 9 shows two cause-effect chains of major events in Severn’s life.

Figure 9. Understand (Explaining) cognitive process sample activity

Figure 9. Understand (Explaining) cognitive process sample activity

Apply

The third cognitive process domain, Apply, is defined by Anderson and Krathwohl (2001, p. 75) as “using procedures to perform exercises or solve problems” (p. 77). The authors distinguish between two types of Apply: Executing, and Implementing.

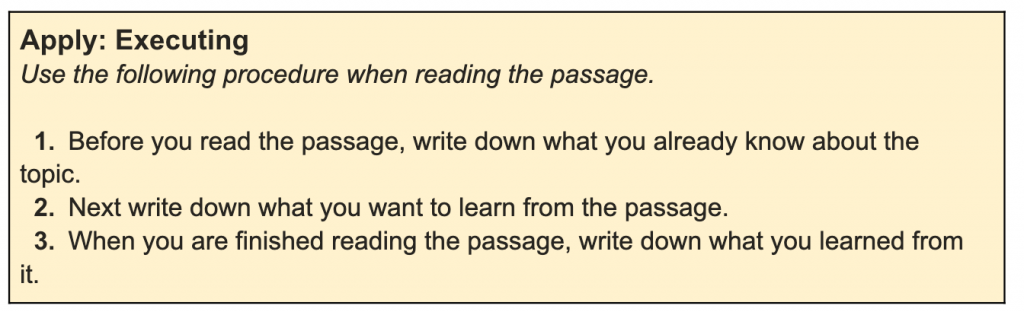

Executing involves “a student routinely carry[ing] out a procedure when confronted with a familiar task (i.e., exercise)” (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001, p. 77). In other words, students do not need to consider what procedure to use to complete the exercise; they simply carry out or ‘execute’ a familiar procedure. For example, students who are practiced in the well-known KWL (Know, Want to Learn, Learned) technique (Ogle, 1986) may automatically use it when faced with a new reading passage[i]. They will, in accordance with the procedural steps, write down what they already know about the topic, followed by some things that they want to learn from the passage and when finished reading it, they will reflect on what they learned from it (see Figure 10 for a summary of the KWL procedural steps).

Figure 10. Apply (Executing) cognitive process sample activity

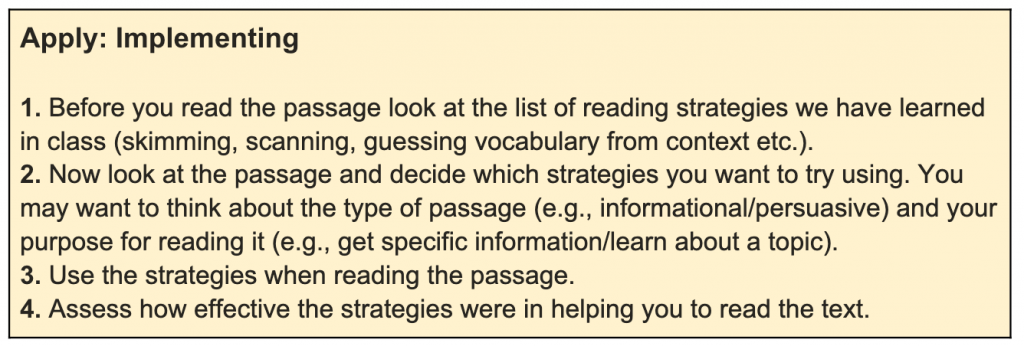

Unlike Executing, Implementing requires that a student “selects and uses a procedure to perform an unfamiliar task” (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001, p. 78). A key feature of Implementing, therefore, is selecting the appropriate procedure to fit the task. Figure 11 shows a simple instructional sequence designed to encourage learners to implement appropriate strategies when reading a passage. In the first step, students review the various reading strategies such as skimming and scanning as well as the purposes for using them. In the second step, they look at the passage and decide which reading strategies they want to use. They then use the strategies they chose to aid them in reading the passage. When finished, students evaluate the effectiveness of the strategies they used. This simple sequence has been called the CUE Technique (Choose Use Evaluate) by the lead author of the paper (Gordon) because it requires students to choose a strategy, use it, and evaluate its effectiveness. As it is introduced prior to reading the passage, it also functions to signal the start, or to ‘cue’ the reading process. When students employ such techniques to decide which strategies are best suited to a particular task, they are using Apply: Implementing.

Figure 11. Apply (Implementing) cognitive process sample activity

Analyze

For Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) Analyze means “breaking material into its constituent parts and determining how the parts are related to one another and to an overall structure” (p. 79). They distinguish between three types of Analyze: Differentiating, Organizing, and Attributing. While Analyze is considered one of the Higher-Order-Thinking Skills, considerable overlap exists between Analyze and other cognitive processes, especially Understand.

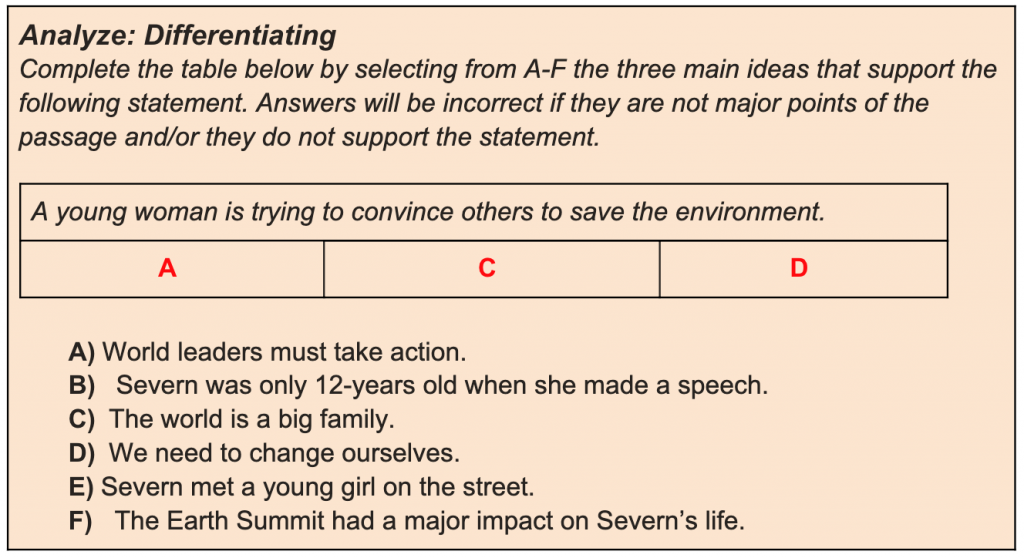

The first Analyze subcategory, Differentiating, for example, is similar to the Comparing subprocess of Understand in their focus on contrasting the features of two or more entities. As Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) argue, however, Differentiating goes beyond comparing surface features of two entities to examining “how the parts fit into the overall structure or whole” (p. 80). Unlike Comparing, which involves simply “detecting similarities and differences between two or more” entities (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001, p. 75), Differentiating requires learners to distinguish parts of a whole structure in terms of their relative significance to the whole (p. 80).

Figure 12 shows a sample Differentiating question type modeled after the TOEFL iBT question-type called “prose summary” (ETS.org, 2016 ). This question-type requires students to not just distinguish between main points and minor details of the passage but to select points that support an overarching statement about the essay (A young woman is trying to convince others to save the environment). Thus, although Option F (The Earth Summit had a major impact on Severn’s life) may be an important point in the essay, it is not a correct choice because it is unrelated to the overarching idea. This question-type, therefore, necessitates Differentiating between the comparative relevance of parts of the essay in terms of the extent to which they relate to the whole.

Figure 12. Analyze (Differentiating) cognitive process sample activity

The second subprocess of Analyze is Organizing, which, according to Anderson and Krathwohl (2001), “involves identifying the elements of a communication or situation and recognizing how they fit together into a coherent structure” (p. 81). As the authors point out, Organizing often occurs together with Differentiating. Students first identify the elements of a passage by differentiating between important and unimportant information. They then determine how these elements fit together in a coherent structure.

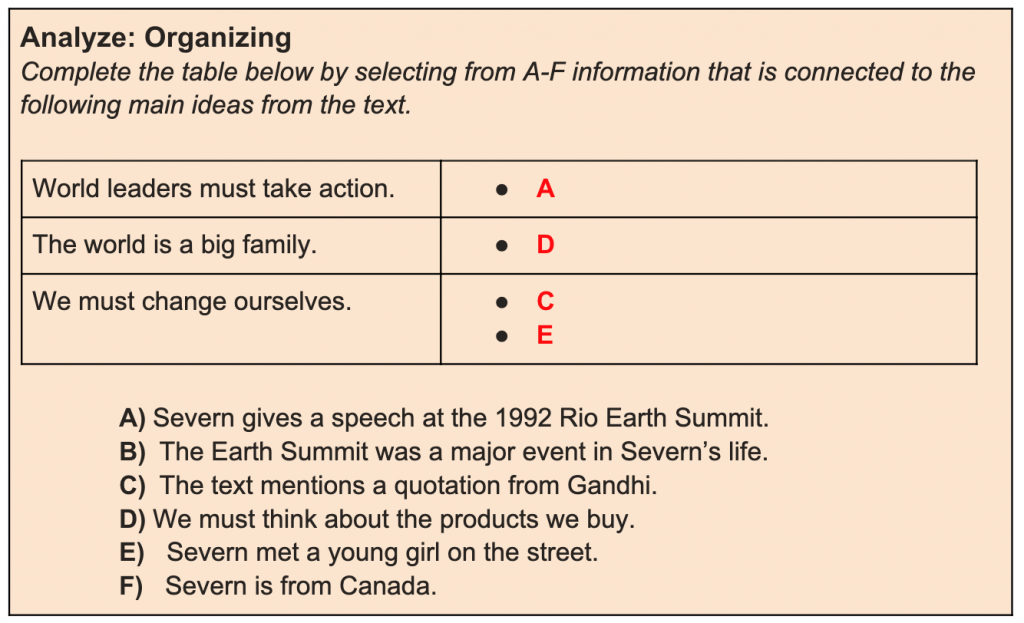

Figure 13 shows a sample Organizing activity modeled after the TOEFL iBT question-type called “fill in a table” (ETS.org, 2016 ). On the left are the three main ideas selected in the previous Differentiating activity (see Figure 12). In the Organizing stage of this analytical process (Figure 13), they have to sort or ‘organize’ the relevant facts and information from the passage next to the appropriate headings.

Figure 13. Analyze (Organizing) cognitive process sample activity

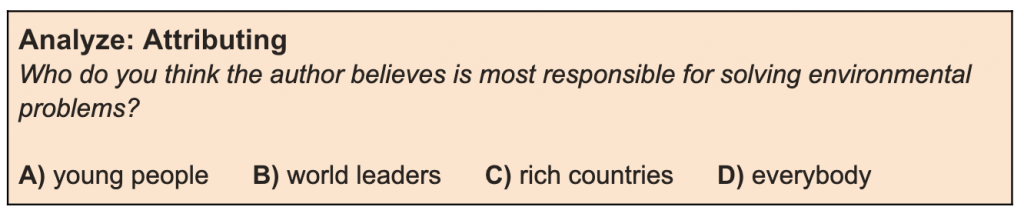

The third and final subprocess of Analyze is Attributing. According to Anderson and Krathwohl (2001), this domain involves a learner “ascertain[ing] the point of view. biases, values, or intention underlying communication” (p. 82). Figure 14 shows a sample Attributing activity in which students must use their understanding of the text to infer who the author believes is most responsible for solving environmental problems (young people, world leaders, rich people, everyone). The answer to this question is not as convergent as others shown here–that is, there may be more than one correct answer. However, after careful consideration, a group and class discussion may reveal that the author devotes a great deal of rhetorical labor to emphasizing the interconnectedness of the world and that it is us (i.e., everyone) who must change our way of thinking about the environment.

Thus, despite the powerful opening of the passage with a quotation from Severn to world leaders (if you can’t fix the environment, please stop breaking it), a class discussion may conclude that the passage is actually quite restrained and uncontentious. It suggests, for example, that it is we who must think about the products we buy from other countries. Nothing is mentioned about any special responsibility corporate leaders or politicians may have to change the way products are made in foreign countries. Obviously, such a discussion would be well beyond the English language abilities of junior high school students, but the initial activity shown in Figure 14 that involves students using evidence from the text to select an appropriate answer may be possible–especially after they have had sufficient time to understand the passage.

Figure 14. Analyze (Attributing) cognitive process sample activity

As this discussion shows, the Attributing subprocess of Analyze begins to take us beyond analyzing a text in order to understand it to critically analyzing the author’s stance and how the reader is positioned to take up particular viewpoints toward the subject-matter. The next cognitive process (Evaluate) takes students further into the domain of opinions to articulate their own viewpoints.

Evaluate

Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) define Evaluate as “making judgments based on criteria and standards” and identify “quality, effectiveness, efficiency, and consistency” as common criteria (p. 83). Thus, if we simply ask students to state their reaction to the reading passage about Cullis-Suzuki in terms of what they thought of it or whether or not it was a good or bad passage, we would not be structuring the task to facilitate evaluation because the opinion is not referenced to some external criteria. Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) identify two subprocesses of evaluation: Checking and Critiquing.

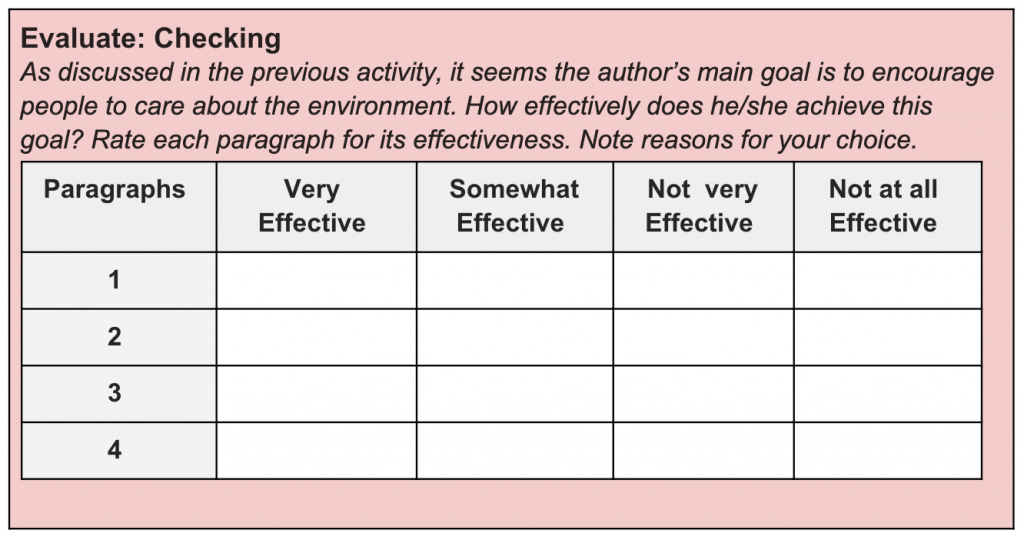

The first of these evaluation subprocesses (Checking) is defined by Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) as “involv[ing] testing for internal inconsistencies or fallacies in an operation or product” (p. 83). Figure 15 shows an Evaluate (Checking) activity. Stated in the instructions for this activity is the authors’ rhetorical goal (encouraging people to care about the environment). The instructions then direct students to determine or ‘check’ how effectively each of the paragraphs in the essay achieved the author’s goal. This goal, therefore, provides the external criteria from which the content of the passage can be compared.

Figure 15. Evaluate (Checking) cognitive process sample activity

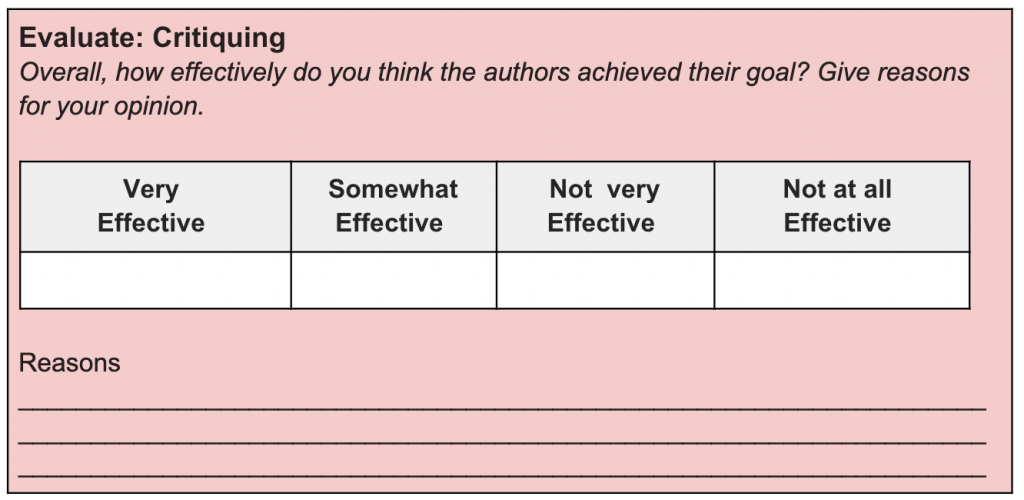

The second Evaluate subprocess, Critiquing, “involves judging a product or operation based on externally imposed criteria and standards” (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001, p. 84). Students, therefore, go beyond simply ‘checking’ the extent to which certain criteria is met to performing an overall judgment based on that criteria.

As the activity in Figure 16 shows, students are to make an overall assessment of the extent to which the authors achieved their goal of encouraging people to care about the environment. They are also asked to give reasons for their choice. This activity could produce a range of responses. What is important is that the evaluation is grounded in evidence from the text. For example, a student might decide that the passage was not very effective because, while Severn’s impassioned speech and the quote about Gandhi were inspiring, the other paragraphs lacked specifics about the seriousness of the climate crisis and the actions that can be taken to address it.

Figure 16. Evaluate (Critiquing) cognitive process sample activity

Create

Of all the cognitive processes in the taxonomy, Create is perhaps the most commonly misunderstood, so it is worthwhile highlighting a few of its key features. First, Create as a cognitive process is different from what is commonly referred to as ‘artistic creativity’. While it involves creative thinking, Create, according to Anderson and Krathwohl (2001), “is not completely free creative expression unconstrained by the demands of the learning task or situation” (p. 85).

Second, Create is built upon a foundation of previous learning. For example, creating a new solution to a problem requires, among other things, understanding the problem itself, evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of existing solutions and developing a product that more effectively addresses the problem. As Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) point out, Create “is generally coordinated with the student’s previous learning experiences [and] is likely to require aspects of each of the earlier cognitive process categories to some extent…” (pp. 84-85). Third, Create requires not only originality but synthesis of existing information or ideas–that is, it involves “mentally reorganizing some elements or parts into a pattern or structure not clearly present before” (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001, p. 84).

Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) break down the Create process into three phases: 1) Problem Representation, which includes generating solutions to a problem, 2) Solution Planning, “in which a student examines the possibilities and devises a workable plan”, and 3) Solution Execution, which occurs when the plan is successfully carried out (p. 85). Figure 17 shows a sample Create activity based on the reading passage about Severn Cullis-Suzuki’s environmental activism.

Figure 17. Create cognitive process sample activity

This activity (Figure 17) includes all of the key features of a Create activity. First, it does not just require a free expression of ideas; students have to develop a concrete plan to respond to a real social issue of relevance to students in their school. Second, it is embedded in their previous learning. Students are responding to a specific problem directly arising from the reading passage–that is, how to encourage members of their community to do more to protect the environment. Example solutions students might come up with are an environmental poster campaign, changes to the school’s recycling policies, invitation or dialogue with environmental leaders etc. The key is that the learning from the reading passage is providing stimulus for creative action.

Reflective Diary Summaries by Course Participants

In the first session of the MA TESOL practicum for in-service teachers, course participants were introduced to the various processes and subprocesses of Bloom’s Taxonomy and asked to make at least three entries throughout the semester to their reflective journals on the following topic:

To what extent have our discussions of Bloom’s Taxonomy in this course caused you to examine your teaching? Please be sure to include specific details and examples. Possible areas you might discuss are the teaching materials or textbooks you use, the goals and objectives of your institution/Ministry of Education, the particular activities you use in your classroom or the tests your students take.

Three of the course participants then wrote 200 word summaries of their reflective journal entries, including one by the lead author and course. Participants also worked together to analyze the entries and identify themes among them. The individual entries are shown below, followed by the analysis of their key themes.

Sina Takada

One of the major difficulties I face as a novice teacher is understanding what I am doing in the class. What an activity looks like does not determine what students are actually learning. For instance, memorized dialogues are commonly used for speaking activities, but referring to Bloom’s taxonomy, I found they only require Remember, the lowest of LOTS. Obviously, oral communication involves so much more than that. However, just because such activities do not involve certain thinking skills does not mean they are of no use. Instead of abandoning the task altogether, I could consider ways to adapt it by making some small modifications. For example, I can possibly upgrade it to Understand by making it a Summarizing activity, or Apply with a follow-up roleplay. While I have been able to use LOTS relatively smoothly, integrating HOTS in my conversation class has been somewhat more challenging. However, it seems possible to integrate it into learner development. Developing learner autonomy is one of my goals, and, therefore, HOTS plays an important role. In future classes, such skills as Analyse and Evaluate will be critical, especially for reflecting on the learning process, but Create, which could involve having learners design their own unique learning activities, will be a fascinating component to include as well.

Kazune Aida

Several years ago, one of my students participated in a speech contest for high school students. It was my first time to help a student write a long speech and we both had difficulties developing the argument of the speech. The topic was free choice, and my student tried to emphasize “the importance of making effort” based on her experience in the volleyball club. Although she delivered her speech passionately, it seemed that her speech ended up just telling her story to the audience. When I came across the definition of Create in Bloom’s Taxonomy, I realized that this is a useful viewpoint for developing the argument of the speech. Since high school students are still teenaged school kids, they choose a topic from their personal experience and the argument tends to depend on their feelings. However, if their experience is deeply ‘analyzed’ and critically ‘evaluated’ with other external criteria before they make their final argument, the speech can be more persuasive to the audience. Of course, speeches have different purposes and are written for various audiences to achieve different goals, but I found that Create as outlined in Bloom’s Taxonomy gives teachers a useful perspective when they help their students make speeches.

Gordon Myskow

While I was teaching in the MA TESOL graduate course, I was also teaching university-level CLIL-based world history courses. Although my course design was informed by Bloom’s Taxonomy, the reflective process in the MA course helped me to gain several new insights into them. I was reminded of the importance of providing adequate time for preparation before having students perform tasks involving higher-order cognitive abilities. For example, in one class, the task was to apply a framework for analyzing sociopolitical change to a contemporary event. Although we had covered this framework in class and I did not perceive the concepts to be overly challenging, I noticed that some of the students struggled when applying the framework to a new historical situation. It seemed they did not understand the concepts as well as I had thought. In retrospect, I should have provided more opportunities for them to show they understood it by having them explain it in their own words or answering questions about it. Another point that I reflected on was that I do not provide much opportunity for students to employ the skill Create. This is an area I intend to work on more when I plan this course in the future.

Key themes from our reflective diaries

The following three key themes that we identified in our analysis of our reflective diary entries about Bloom’s Taxonomy are elaborated below.

- Increased awareness of the over/under emphasis of some cognitive processes

All of us mentioned in our reflective diaries that Bloom’s Taxonomy helped us gain deeper insight into the types of cognitive processes that receive more or less emphasis in our teaching contexts. Sina mentioned that some speaking activities in his context are focused on having students Remember language features, while Gordon observed a lack of emphasis on the higher-order process Create in his CLIL-based courses. Similarly, Kazune noted that some highly emotionally-charged speeches do not always meet the definition of Create in Bloom’s Taxonomy. - Challenges of incorporating higher-order thinking skills into classes

We also mentioned some of the challenges of effectively implementing higher-order cognitive processes in our teaching contexts. Gordon wrote about how students in his context had difficulty applying a framework they learned to a new situation. Likewise, Sina wrote that while he has implemented LOTS ‘relatively smoothly’ in his classes, HOTS has been more challenging. Kazune noted the difficulty some students have supporting their views in speeches with a ‘critical evaluation and ‘a deep analysis’ of their own experience with other factual information”.

- Importance of scaffolding higher-order thinking skills

A third theme that emerged in our reflective diaries is the need to provide a more systematic or step-by-step approach to addressing higher-order thinking skills.

While Gordon recognizes that more support was needed to prepare his learners in his CLIL-based world history course to perform higher-order thinking tasks, Kazune concludes that Bloom’s Taxonomy provides “a useful perspective” for supporting the integration of higher-order thinking skills in the speech creation process. Sina suggests a modest, incremental approach in which existing activities are modified to integrate skills such as Summarizing.

Conclusion

In this paper, we shared our reflections from a TESOL graduate course in which we used Bloom’s Taxonomy as a resource for reflection and exploration of our teaching. In our analysis of our reflections we identified the following three themes: 1) increased awareness of the over/under emphasis of some cognitive processes in our teaching contexts, 2) the challenges of incorporating higher-order thinking skills into classes, and 3) the importance of scaffolding higher-order thinking skills.

As this discussion shows, our use of Bloom’s Taxonomy as a reflective tool enabled us not only to examine the extent to which our classes promote the use of higher or lower-order thinking skills, but to identify challenges and consider solutions to them. In other words, the process helped promote greater teacher autonomy–a concept defined previously as “the capacity, freedom, and/or responsibility to make choices concerning one’s own teaching” (Aoki, 2002, p. 111).

Also included in this paper is an in-depth overview of the various cognitive processes and sub-processes of Bloom’s Taxonomy. These processes were illustrated using sample activities based on a reading passage from an EFL textbook passage on the topic of environmental activism for second-year junior high school students in Japan. One reason for selecting this particular passage was to illustrate how activities that promote higher-order thinking abilities can be implemented even with young learners of very limited English ability.

An important feature of these activities that makes this possible is their design. Very few of the activities shown here are open-ended tasks that require students to produce their own unique responses; instead they are mostly closed-tasks in which students simply select the most appropriate response and explain the reasons for their choice. This design feature may be one technique for teachers to scaffold the learning burden of higher-order thinking skills. With careful consideration of our learning context we may be able to cultivate the kind of fertile ground where autonomy may ‘bloom’ for both teachers and students.

References

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.) (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Aoki, N. (2002). Aspects of teacher autonomy: Capacity, freedom, and responsibility. In P. Benson & S. Toogood (Eds.), Learner autonomy 7: Challenges to research and practice (pp. 111-124). Dublin: Authentik.

Ball, P., Kelly, K., & Clegg, J. (2015). Putting CLIL into practice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Bloom, B.S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: The cognitive domain. New York: McKay.

Dalton-Puffer, C. (2013). A construct of cognitive discourse functions for conceptualising content-language integration in CLIL and multilingual education. European Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1(2), 216-253.

ETS.org (2016). Inside the TOEFL® Test – Reading Prose Summary & Fill in a Table Questions. Retrieved from https://www.ets.org/s/toefl/flash/34228_toefl2016-r6_transcript.html

Mineshima, M. (2015). How critical thinking is taught in high school English textbooks. In P. Clements, A. Krause, & H. Brown (Eds.), JALT2014 Conference Proceedings. Tokyo: JALT.

Myskow, G., Bennett, P. A., Yoshimura, H., Gruendel, K., Marutani, T., Hano, K., & Li, T. (2018). Fostering collaborative autonomy: The roles of cooperative and collaborative learning. Relay Journal, 1 (2), 360-381. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1VFzYlwTHIKaaeezv43wXcmVPoLo0Q-gl/view

Ogle, D. (1986). K-W-L: A teaching model that develops active reading of expository text. The Reading Teacher, 39, 564-570. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/20199156

Okada, R. (2015). Thinking in the Japanese Classroom. Journal of Modern Education Review, 5(11), 1054–1060.

Smith, R.C. (2003). Teacher education for teacher-learner autonomy. In J. Gollin, G Ferguson, & H. Trapes-Lomax (eds), Symposium for Language Teacher Educators: Papers from Three IALS Symposia. Edinburgh: IALS, University of Edinburgh. http://homepages.warwick.ac.uk/~elsdr/Teacher_autonomy.pdf

Sunshine 2 (2011). Sunshine English Course 2. Tokyo: Kairyudo.

[i] In lectures by the lead author of this paper, Ogle’s (1986) KWL technique is often elaborated as the AWLS Technique (Already Know, Want to Learn, Learned, Still Want to Learn) to emphasize that the learning process is never complete—that all present learning contains the seeds for future learning.

Thank you so much for your wonderful paper. I am familiar with the taxonomy and frequently refer to it in my own lesson and syllabus design, but I felt your paper helped me understand it even better. It clarified the changes made between the original taxonomy and the revised one. The activities you include highlight exactly why the shift from nouns (e.g. synthesis) to verbs (e.g. create) was necessary. Thinking is an active process and the activities that get students thinking should actively engage them.

I’m really glad that this piece emphasizes the classroom teacher as the ‘point of sale’ for legitimizing and implementing Bloom’s Taxonomy. I frequently sense, in conversations with other educators, that they are theoretically on board with integrating it into their classrooms, but they cannot always conceptualize what it might actually look like in materials or “in action” and therefore do not include them. The examples that you include here, connected with the detailed description of the taxonomy, will result in more readers being able to put Bloom into practice. In particular, I liked the examples for summarizing (Figure 6), analyzing (Figure 12), and evaluating (Figure 15). I would like to try and create similar activities for my students.

A strength of this article is the honesty of the teachers in their reflections. They all comfortably express beliefs, acknowledge strengths, and identify areas for improvement. As Tom Farrell said at JALT2014, “self-reflection is not self-flagellation.” These pieces model healthy reflective practice to other educators and hopefully it will motivate more teachers to engage in it themselves. It was my natural instinct as I read the text to reflect on my own work and I can only hope others do too.

Much as some of you did, I noticed that I myself rely on 2 or 3 elements rather than all the processes consistently. This piece has given me serious food for thought as well as motivation to keep integrating Bloom’s taxonomy into my classroom. I think this was a goal of the piece as the abstract referred to the empowerment of teachers to make informed choices. In fact, I will be recommending this to teachers as one potential “lens for critical analysis” through which to view their materials, beliefs, and practices. Thanks again for your thoughtful piece!

Thank you very much for your supportive review. As one of the teachers that put self reflection in it, I am really glad that you mentioned the importance of reflection. It surprised me when I found how much limited many of my classroom activities were, in terms of incorporating thinking skills. While incorporating higher thinking skills is bit of a challenge, I believe this piece helps us bring them in our classroom.

I agree, it can be challenging, but it’s a worthy challenge that is worth doing! I thought I had more variety in what I was doing as well, so this chance to reflect really reminded me to diversify my tasks and approaches.

Thank you so much for your positive and supportive feedback on our paper. I was very happy to hear that you think the paper may be of use to other educators. We are very fortunate to have a reviewer with so much familiarity not only with Bloom’s Taxonomy but with the literature on reflective practices. Your comments also pulled on a lot of interesting threads that I would like to explore further.

Your point that the change in the new taxonomy from nouns (things) to verbs (activities) to describe cognitive processes got me thinking more about the taxonomy’s relevance to MEXT’s focus on active learning, especially the deep learning (fukai-manabi) dimension of it. I know there is quite a bit of talk about that already, but I am becoming more convinced of its usefulness for MEXT teacher education.

And I couldn’t agree more about the taxonomy being potentially very empowering for teachers! I think there is often an assumption that course developers will integrate the various cognitive processes of the taxonomy into textbooks and materials and that if teachers just follow the textbooks, they will be addressing a range of lower- and higher-order instructional objectives. But as I often see in my own casual observations of popular textbooks, they typically address a very narrow set of cognitive processes, almost always at the lower end of the spectrum. And as you also point out, it is often not so straightforward for teachers to incorporate the framework into their lesson planning, even if they are on board with it and recognize its value. It seems to be very much one of those often-talked-about-but-under-utilized frameworks.

Finally, your observation about “healthy reflective practices” is another thread I would like to pull on more in the future. Becoming aware of the gap between what we think we are doing in the classroom and what is actually happening may be a necessary condition for teacher development, but not always a pleasant one. As a teacher educator, it is always worth reminding myself of this.

Thank you again for your very helpful feedback!

I think that many teachers may be already doing tasks that support HOTs, but they don’t have the metalanguage to confidently say they are, so I agree that introducing this as a part of MEXT education can help teachers learn and talk about their craft more effectively (and confidently!).

Healthy reflection is so important. Many people want to focus on what they did wrong or how they could improve without recognizing that part of reflective practice is understanding why you are doing what you are doing. Perhaps something didn’t work smoothly, but you have a clear idea of why you designed a particular activity the way you did. If you know why you’re doing it, you can figure out how to modify it in a way that improves while remaining confident in the initial choices you made as an educator. Being principled is crucial.

Thank you very much for your feedback. I am very glad to have your positive comment on our paper.