Adrianne Verla Uchida, Nihon University

Uchida, A. V. (2020). Integrating the four-dimensional education framework into an EFL course curriculum. Relay Journal, 3(1), 25-47. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/030103

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

A part of being in academia is moving from institution to institution. This paper will showcase the work of one educator as they adjusted to a new teaching context in 2018. With a desire to conduct practitioner research (Mann & Walsh, 2017), the instructor designed a course for their university EFL classes using the required grammar textbook and the Center for Curriculum Redesign’s Four-Dimensional Education Framework (Fadel, Bialik, & Trilling, 2015). Tasks and projects were designed to connect each grammar unit with activities designed to utilize the elements of the framework to motivate the students to take an active role in their learning. This paper will introduce the context, the Four-Dimensional Education framework, the course activities, and the results of a semester-long research project in hopes that other educators may be inspired to integrate the framework and similar learning initiatives in their own classrooms and teaching contexts.

Keywords: Curriculum design, Four-Dimensional Education Framework, project-based learning, task-based learning

This practitioner research project (Mann & Walsh, 2017) started as I, the teacher-researcher of this study, began working in a new full-time position at a private university in central Japan in the spring of 2018. Moving to a new working environment is always a challenge; however, this position required making use of my Japanese language ability and emphasized an expectation to research and publish more than any part- or full-time positions I had held previously. These changes compelled me to look at my new position and institution with a fresh outlook. Wadden and Hale (2019) recommend that educators “approach [their] particular school the way an anthropologist investigates a foreign culture: put aside [their] personal assumptions and cultural predilections and observe as clearly as possible the actual environment in which [they] work” (p. 7). Similarly, I believed that my new working environment, where I had limited preconceived notions of the curriculum, the students, and the institution, would provide me with opportunities to carry out practitioner-based research objectively while acclimating myself to the new teaching and researching context.

The university is comprised of non-English majors; however, the curriculum has a strong focus on English language study in the first year. Completing English I through English IV is required for graduation. While all categorized as four-skill courses, English I and III place an emphasis on speaking and listening, while English II and IV emphasize reading, writing, and grammar. In addition, various elective courses teaching presentation, academic writing, and test preparation are available for students to take throughout their university careers. Moreover, many students choose to study a second foreign language in addition to English. Therefore, it can be said that foreign language study plays a pivotal role in the students’ university studies. This paper will focus on the design, implementation, and results of the teacher-researcher’s spring semester English II course. While this paper focuses on one teacher-researcher’s English-as-a-foreign-language course, the framework used to design the course was not specifically designed for a language course and can be utilized for a variety of subjects or across a curriculum. Therefore, it is hoped that this paper will appeal to not only EFL-related educators, but also any educator who is interested in curriculum design, learner autonomy, and preparing learners to thrive in the 21st century.

The Four-Dimensional Education Framework

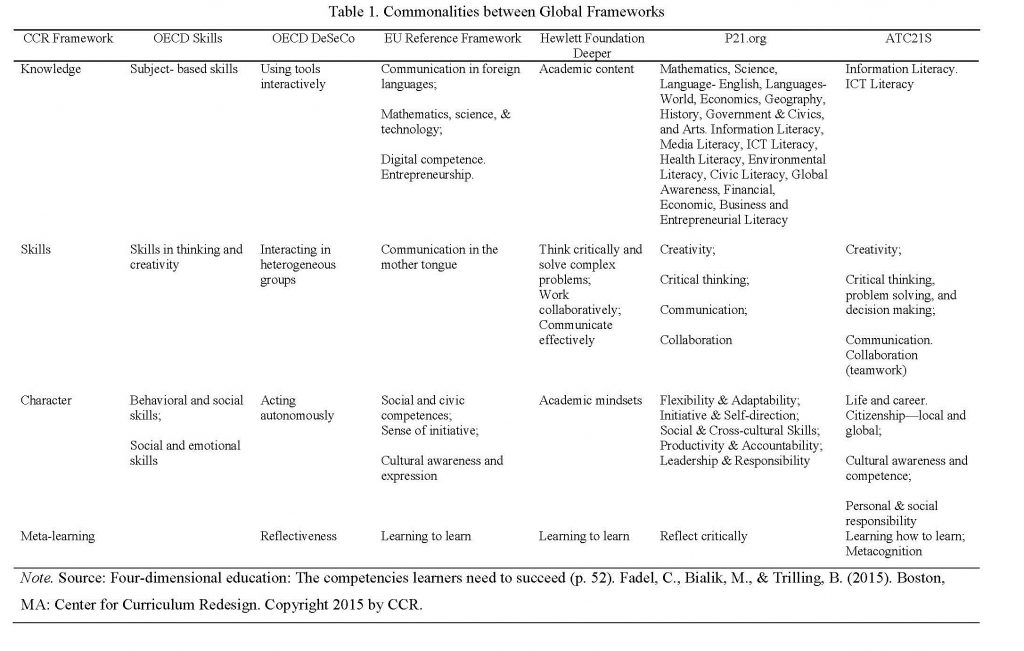

With the advancement of society in the 21st century, there have been various milestones and episodes of change across the globe. Some examples include the increase in human lifespan, the dissemination of smart devices, the spread of the Internet, and the development of virtual education. With these developments, a need has arisen to develop and usher in new competencies in education to integrate essential 21st century skills into present-day educational systems. Some examples of frameworks used around the world include the Center for Curriculum Redesign’s (CCR) Four-Dimensional Education Framework, P21 Framework for 21st Century Learning, OECD Skills for Innovation, OECD DeSeCo, EU Reference Framework for Key Competencies, and the ATC21S Framework (Fadel, Bialik, & Trilling, 2015). Each of the frameworks incorporates similar elements of skills, knowledge, and character development into the frameworks using various language to represent each category, while there is limited integration of elements of reflective practice (Table 1). After looking at the various frameworks, the CCR Four-Dimensional Education Framework was chosen for this project as it was perceived to meet the needs of the learners most clearly.

The framework also aligned clearly with Little’s (2003) definition of learner autonomy. He states that “learner autonomy requires insight, a positive attitude, a capacity for reflection, and a readiness to be proactive in self-management and in interaction with others,” (p. 2). The framework’s categories of knowledge and meta-learning appeared to compliment Little’s opinion that autonomy requires insight. Furthermore, there was a clear connection between the concepts of reflection and meta-learning. Little’s definition also placed value on the importance of character when he stated that autonomy needs “a positive attitude” and the ability to take control of one’s actions through “self-management,” (2003, p. 2). Finally, the concept of being forward-thinking when working with others has clear links to the framework’s skill category. These two resources appeared to provide a solid foundation for the design and implementation of the course.

Table 1. Commonalities between Global Frameworks

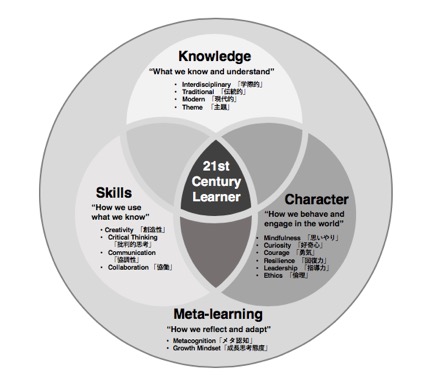

The Four-Dimensional Education Framework (Figure 1) was designed to address the shift in education needed to prepare students for excelling in the current century as “21st century learners” (Fadel et al., 2015). They emphasize that the framework combines into the curriculum the integration of “knowledge (what students know and understand);” “skills (how they use that knowledge);” “character (how they behave and engage in the world);” and “meta-learning (how they reflect on themselves and adapt by continuing to learn and grow towards their goals)” (p. 6). Each of the four categories are further divided into subcategories that will be explained in more detail below.

Figure 1. Four-Dimensional Educational Framework by CCR.

This figure illustrates qualities that a 21st century learner needs to succeed.

Adapted from Four-dimensional education: The competencies learners need to succeed (p. 67). Fadel, C., Bialik, M., & Trilling, B. (2015). Boston, MA: Center for Curriculum Redesign. Copyright 2015 by CCR. Bilingual adaptation used with permission. Template design copyright 2018 by PresentationGO.com

Knowledge

Fadel et al. (2015) explain that the dissemination of knowledge has been the foundation of education for centuries. Since the sixth century, Western knowledge has been focused on the Trivium (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) and the Quadrivium (astronomy, geometry, music, and arithmetic), which today are considered to be the foundations for a liberal arts education. With the passage of time those themes developed into the familiar subjects of math, science, language arts, foreign languages, social studies, arts, and physical education. However, Fadel et al. (2015) argue that knowledge needs to be developed further to make each construct more interdisciplinary in order to address the development of society in the 21st century. Examples include making connections between people and organizations as well as using big data and new media to deepen student knowledge. Moreover, global literacy, information literacy, and digital literacy are emphasized as essential themes for learners to master.

Skills

The framework divides skills into four subcategories: creativity, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration. These skills were chosen based on data collected from psychology research, academic articles, news sources discussing gaps between education and employer needs, and various educational stakeholders including ministries and departments of education around the world.

Creativity is traditionally associated with the arts; however, presently the definition has been expanded to include broader fields such as design thinking and entrepreneurship (Fadel et al., 2015). Moreover, creative thinkers have the ability to engage in “divergent-thinking abilities, including idea production, fluency, flexibility, and originality” (Guilford, 1968 as cited in Fadel et al., 2015, p. 112).

Critical thinking as defined in the framework follows the National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking’s definition, which states that it is the “intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action” (National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking, 1987, Defining Critical Thinking).

Communication skills are a vital 21st century skill and can be crucial in our globalized world where interactions between people are essential, both within one’s own culture and cross-culturally. Developing learners’ abilities to give instructions, negotiate, discuss, debate, and problem-solve are just a few of the ways that they can practice authentic communication through learning. Developing communication skills also hones two more abilities that are essential in today’s workforce—those of self-expression and teamwork (Fadel et al., 2015).

Collaboration, similar to communication, can take place in homogeneous environments but is also essential among multicultural environments and situations in today’s globalized world. The framework describes collaboration as “the joining together of multiple individuals in service of working toward a common goal” (Fadel et al., 2015, p. 120). Moreover, Fadel et al. (2015) state that collaboration can have a positive effect on learning outcomes, student enjoyment of subject matter, and learner self-esteem.

Character

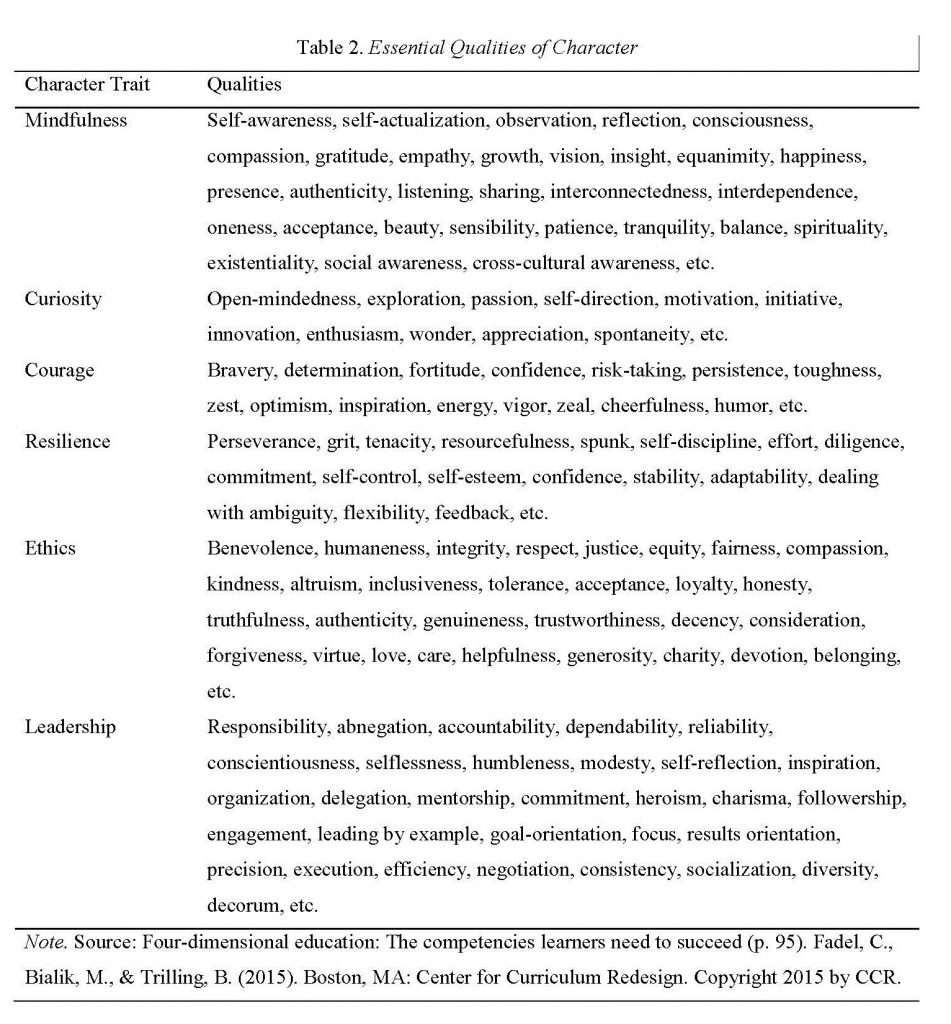

The character dimension of the framework focuses on the following categories of character traits: mindfulness, curiosity, courage, resilience, leadership, and ethics with each category expanded to include a wider range of associated qualities and concepts (Table 2). Fadel et al. (2015) state that “since ancient times, the goal of education has been to cultivate confident and compassionate students who become successful learners, contribute to their communities, and serve society as ethical citizens” (p. 123). This continues to be true today as educational bodies focus on fostering learners with a global perspective.

Meta-learning

Where the CCR’s framework stands out compared to other frameworks is its emphasis on meta-learning. Fadel et al. (2015) feel that this dimension places emphasis on the reflection of one’s own learning and developing a growth mindset (Dweck, 2017) that fosters learners’ abilities to adapt to various contexts and situations in addition to developing their ability to pursue their goals and not give up when facing challenges. This dimension allows learners to be “versatile, reflective, self-directed, and self-reliant” (Fadel et al., 2015, p. 145). The framework encourages learners to develop their metacognition skills by reflecting on their learning goals, learning strategies, and learning outcomes to understand their current feelings and beliefs in relation to their goals and desired outcomes (Fadel et al., 2015).

Connecting the Framework to the Japanese Context

From 2008 to 2017, the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, and Science (MEXT) set out to improve education in Japan with the implementation of the First Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education, followed by the Second Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education (MEXT, n.d.). The focus of the second plan begins by stating, “What is truly needed in Japan is independent-minded learning by individuals in order to realize independence, collaboration, and creativity” (MEXT, n.d., Pamphlet heading). This fundamental goal connects most obviously to the skills and character dimensions of the Four-Dimensional Education Framework. One example of efforts to draw attention to the areas of skills and character development can be seen in the research of Sekiguchi (2017). He administered a questionnaire to junior high school students to analyze perceptions of their skills and character development (Sekiguchi, 2017). The study found connections between the four skills in the framework and various subcategories of the character dimension. While MEXT has been making efforts to prepare learners in Japan for the 21st century and trying to implement broad policy changes to improve education (Kimura & Tatsuno, 2017), the practical implementation of said policies generally fall on the individual institutions or individual instructors. Therefore, the decision to use the CCR’s framework as the base for my course seemed aligned with the goals of MEXT.

Methodology

The university requires students in my section of English II to cover all of the material in the Oxford English Grammar Course Intermediate textbook (Swan & Walter, 2011). The textbook is divided into 22 sections based on different grammar structures; for example, Section 4 provides explanations and drills reviewing past tense; Section 6 places its focus on explanations and drills using modals verbs. Each section is divided into two parts; the first, “Revise,” begins with a review of basic grammar rules and a variety of grammar drills to practice. This is followed by the second part, “Level 2,” which introduces more difficult grammar patterns and drills for student practice. Simon Borg (2016) observes that while in recent years various communicative styles of language teaching have emerged, in many classrooms, “grammar remains the driving force and the way it is taught has changed very little over the years.”

While grammar comprehension is essential for language acquisition and the belief that students need to be taught grammar structures to produce accurate English still persists (Little, Dam, & Legenhausen, 2017), the textbook’s intense focus on grammar had the potential to negatively impact student motivation and their sense of autonomy, which seemed at odds with my desire, as the instructor, to foster a communicative learning environment. Furthermore, Borg (2017) states that focusing on the completion of discrete-item exercises similar to the exercises found in the required course textbook had the potential to reduce English learning to the ability to answer and complete such styled questions, which is far removed from communicative language learning.

Thankfully, the university does not specify how classes must be designed and implemented, allowing the instructor the autonomy to implement the required textbook in the course as they see fit. This allowed me to integrate the textbook into the course while staying true to my teaching style and beliefs, something which is essential to being a TESOL professional (Farrell, 2015). To provide students with in-class time to actively engage in using English, the 22 textbook units were assigned as homework. By flipping the classroom (Bergmann & Sams, 2012; 2014) the grammar tasks could be assigned outside of class allowing students to learn and/or review the grammar points at their own pace before arriving in class prepared to apply what they had studied and drilled at home in the various classroom tasks and projects. The activities were designed using the principles of task-based learning (Nunan, 2004) and project-based learning (Beckett & Miller, 2006). The course included five one-lesson tasks (Appendix A) and six multi-lesson projects (Appendix B) (For a detailed description of two activities, see Verla Uchida, 2019).

Each in-class activity was designed with the hope of motivating the learners to develop their English language skills while also developing their sense of learner agency and learner autonomy. These tasks and projects were designed to allow students to “engage in activities that they find personally meaningful” (Noels, 2013, p. 27) from the first day they entered the classroom, through use of the target language. Each activity required the students to make a plan, implement it, and then evaluate their performance through self-reflection, similar to what Little et al. (2017) refer to as the teaching-learning cycle in the autonomy classroom. Additionally, the activities were designed to be interactive and require collaboration, in order to foster their L2 identities and deepen their motivation. In order to do this, I aligned myself to not be perceived as the instructor imparting knowledge onto my students but rather the facilitator and coordinator of the activities, as well as an adviser, helper, and resource to help the students in the completion of the activities (Benson, 2013). Moving myself into that position required the students to “take charge of [their] learning” (Holec, 1981, p. 3).

The data used for this study were collected and analyzed using mixed methods. The educator kept a teaching journal during the course (Farrell, 2015) to document class observations, reflect on the various tasks and projects, and note any additional concerns or ideas gathered during the course. Additionally, students completed an open-ended reflection sheet (Appendix C) at the conclusion of every class, briefly noting their thoughts about the activities or overall impressions. The data was then coded by taking notes on key words, patterns, and repetitive phrases, which were then matched to the CCR’s Four-Dimensional Education Framework. Finally, a bilingual online survey using Google Forms was administered at the conclusion of the semester to gather students’ impressions regarding the course, the activities, and their perceptions of their English abilities (Appendix D). Students had the option to choose to answer in English or Japanese. All answers given in Japanese were translated into English by the author.

It must be noted that the foundations of this qualitative research project are based on practitioner research (Mann & Walsh, 2017) and action research (Burns, 2009), and therefore, the research and instructor are the same person. To limit potential bias, the data collected from students were not connected to their grades, and the teacher journal entries were based on observations collected during the class, with the intention of limiting subjectivity as much as possible during data collection.

Results

The results of this study were compiled using the qualitative data collected from all of the students’ reflection sheets and both qualitative and quantitative data collected from the student surveys. Of the 78 students who were enrolled in the course, 39 students voluntarily participated in the survey. The teaching journal provided critical reflection on the class tasks and projects as well as classroom dynamics but was not utilized enough throughout the semester, due to limited time constraints and other research and administrative responsibilities. The journal provided examples of the students utilizing the framework in various tasks in addition to the midterm and final group projects.

The overall findings of this study clearly show that the majority of students reported being nervous and/or worried about English classes but also excited to study English at university at the beginning of the semester. Many students wrote that having “a native teacher” was the reason for both of those feelings. Upon completion of the course students were asked, “Do you think your confidence level in your English ability has changed since taking this course?” Eighty percent of respondents said “yes,” while 20% said “no.” Some reasons given for feelings of confidence in their abilities include, “because I spoke and wrote English many times,” and “my test score improved over the semester,” while those who felt they did not gain confidence said, “I didn’t have confidence to speak in English, so I didn’t use much English in class so I can’t say I gained confidence,” and “I need more opportunities to practice before I can say I am confident.”

Furthermore, 90% of the students said they felt their motivation level had improved over the course of the semester, whereas 8% said that they did not feel that way, and 2% said that they were “unsure.” In the optional follow-up question “Please explain the reasons for your answer to the above question,” those who said that they were motivated commented on the activities done in class and the opportunities to work with their fellow motivated classmates as reasons for their increased motivation. One student who said that they were unsure attributed it to the fact that they felt that their motivation level stayed the same throughout the course. Those who answered no cited feeling that the level of the course was too high for their abilities.

Moreover, while the students did not explicitly learn about the framework being used in the course, at the conclusion of the semester, when asked, “What knowledge did you gain or learn in this class?” 60% of respondents identified areas they had gained knowledge in or learned about by stating that they had learned about digital literacy, 23% reported that their grammar or writing skills had improved, and 12.5% believed that they had gained the ability of English expression. Students listed examples of gaining this knowledge through having opportunities to write paragraphs and give presentations in English, using the Internet to find information (media literacy), and utilizing Google Classroom to prepare class assignments (digital literacy).

When asked, “Which of the following skills did you develop?” 80% of respondents said that they had developed their communication ability, 43.6% said creativity, 28% said collaboration, and 0% said critical thinking ability. Students provided specific examples from the course, citing examples including doing group work, participating in field work, making presentations, and developing discussion skills.

Regarding the development of character during the class, 64% of respondents said that they had developed curiosity and courage during the course, followed by 49% saying that they had developed mindfulness. Less than 5% of respondents chose resilience, and less than 3% chose ethics and leadership. Most respondents said that they developed these character traits through making and giving presentations and doing group work. Students noted developing these traits through group work on projects and tasks and through writing their class reflections.

While the concept of meta-learning seemed too difficult for students to grasp immediately in the survey, they were very familiar with reflective writing. Therefore, regarding metacognition and a growth mindset, students were asked, “How useful was the reflection writing to you throughout the semester?” Using a five-point Likert scale, 5% of students found that reflection writing was not useful because it was hard; 31% said that it was neither useful nor not useful but gave positive reasons for doing it, including “it improved my writing skills,” “It was usual,” and “I did it many times.” 54% said that it was useful, and 10% said that it was very useful. Some of the reasons given for the usefulness of reflective writing include, “I could look back on what was done in class and then reflect on it,” “I could reflect on myself and then think about what to do next,” and “This work is done by only me. I can check how to write and think alone.”

The student reflection sheets were analyzed by looking for terms related to the framework and the mention of specific tasks and projects. Students most commonly included comments focusing on their emotional reactions to specific class activities and tasks. From the survey results, students reported that the midterm restaurant review project (20%) and the final local sightseeing project (18%) were their favorite activities during the semester despite both involving out-of-class field work and the possibility of costing a small amount of money to complete the projects. Regarding the framework, the students reported the development of the following character traits: courage (64%), curiosity (64%), and mindfulness (49%). The majority of students said that these developments were due to a desire to learn new things and visit new places, the chance to work with classmates in randomly assigned groups or pairs, and because of the teamwork required to design presentations for the high-stakes midterm and final exams. Student reflections also showed the development of their individual characters through the use of emotive words in reflection entries, for example: “I enjoyed speaking English,” “Class is interesting and fun,” “I’m annoyed about today’s presentation because I can’t say what I want to say,” and “I’m looking forward to the next class every day.”

Discussion

The overall findings of this study clearly show that students reported developing various forms of knowledge, skills, character traits, and metacognitive abilities by participating in this course and completing the tasks and projects assigned to them. Therefore, it can be said that using the framework as a base for the course design was successful.

Students recognized that they developed their communication skills by forming relationships with many of their classmates through pair and group work, enabling them to discuss and reflect on the various classroom assignments. They learned the skills necessary to manage their time to make interesting final products and presentations together, in addition to being able to speak positively about a variety of topics in English. Fink (2013) argues that communication can take place through skill development—data gathering, foreign language use, and managing projects—which mirrors the student impressions above. The students displayed their communication skills exceptionally while completing their midterm restaurant reviews. The students spent time in class discussing the restaurant they wanted to visit while taking into consideration various issues, including the ease of transportation to and from the restaurant as well as the budget each student would need to eat at their chosen restaurant. After visiting the restaurant, the students then had to communicate about how to design their group presentations and facilitate roles for each participant. Furthermore, regarding communication, Fadel et al. (2015) explain that group work allows participants to “learn, measure, and get feedback on the growth of true communication skills,” (p. 77). The students mentioned similar comments in their reflections.

The results also show that students demonstrated acts of collaboration, or what Fadel et al. (2015) refer to as “working toward a common goal,” (p. 78) by making slides together, helping each other, cooperating with their partners and group members during tasks and projects, participating in field work together, and working together to improve their English skills. This could be seen most clearly in their final projects. Students began by brainstorming about the local area to choose the places their group wanted to introduce and visit for their local area tour final presentations. They then worked together to find time in their schedule to visit each place and take photographs and/or video. Next, they designed a slideshow presentation and webpage as a group and presented it to the class. This is a clear example of the students demonstrating their autonomy in planning, implementing, and evaluating (Little et al., 2017). Additionally, the act of collaboration in completing the group project shows that “autonomy does not happen in isolation but through interactions involving peers and teachers (O’Leary, 2018, p. 62). Moreover, the act of collaboration matches what Snyder (2019) calls “the ultimate goal: a collaborative classroom community” (p. 142). By the end of the semester, through collaboration with different classmates for each task and project, the class atmosphere developed into a cohesive and collaborative environment with the students able to comfortably work together in English with a variety of people they had only known for a few months.

However, it must be noted that none of the students in the course believed that they had developed their critical thinking skills throughout the semester. Critical thinking, as mentioned earlier, is the ability to apply, analyze, and/or evaluate through observation, experience, and reflection (The National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking, 1987). From this perspective, there are multiple examples of students actively demonstrating critical thinking both in their survey results and reflections sheets. One explanation for the students’ inability to recognize their critical thinking abilities could be explained by the definitions and interpretations of critical thinking in their native Japanese language. The traditional Japanese definition of critical thinking is hihantekishikō (批判的思考). The Japanese definition of hihan means to look at the good and bad points of something but also can mean to evaluate the points one needs to apologize for or the points of that need improvement (Hihan, n.d.). Additionally, the translation of hihan is usually listed as “criticism” or “judgement” (Hihan 2, n.d.).

Recent research regarding critical thinking used in MEXT educational documents show the use of three distinct terms meaning critical thinking. The most commonly used is the Japanese term explained previously, followed by the foreign loan word kuritikaru shinking (クリティカルシンキング), and lastly, “critical thinking” written in English (Bullsmith, 2019). Bullsmith (2019) explains that hihantekishikō (批判的思考) is most commonly used and “is still clearly understood as the translation of a foreign idea, something brought in from outside, with regular discussion of why it is particularly difficult in the Japanese educational context” (p. 4). Therefore, the fact that students struggled with recognizing that they were performing acts of critical thinking can be understood. It is not that they were not doing it, but rather that they could not recognize that they were doing it.

Interestingly, when the student reflections were analyzed at the conclusion of the course, language and examples exhibiting the development of critical thinking skills were used by the students despite their stated lack of critical thinking skills development from the survey results. Various examples of the students showing their ability to think critically by analyzing and evaluating their own experiences and abilities were documented throughout their reflection sheets (Appendix C). Some examples are as follows: “I need to improve my vocabulary,” “Presentations need a loud, clear voice,” “I speak only in words not sentences,” “I noticed Japanese websites use many words, but English websites use many pictures,” and “It’s challenging to explain one’s own ideas.” Therefore, it can be said that while the students did not recognize the term “critical thinking,” they clearly showed they had the ability to analyze and reflect on their own experiences throughout the course, so it can be said that they did use critical thinking skills from the framework.

One final element worth noting is in regard to students’ character development throughout the semester because, as Williams, Mercer and Ryan (2015) state, “emotions have a facilitatory role to play in language learning” (p. 79). While the character elements of the framework were not directly shared with the students until they were listed as a question on the survey, students often used emotive language that connected to the various character traits in their end-of-class reflections. They were not afraid to share their feelings of excitement, contentment, and anxiety. This is important because, as Fadel et al. (2015) explain, character encompasses a variety of terms including “agency, attitude, behaviors, dispositions, mindsets, personality, temperament, values, beliefs, social and emotional skills, noncognitive skills, and soft skills,” (p. 83) which are all vital for success in speaking a second language.

Finally, the students were able to develop their autonomy by engaging in and completing the various tasks and projects assigned to them throughout the semester. Little (2003) states that insight is a requirement for learner autonomy, and students provided written examples of this through their class reflection sheets and also in their daily interactions when completing the tasks and projects. Verla Uchida (2019) describes a peer-advice column activity that allowed students to share their insights through writing advice columns. Examples throughout this paper attest to the students’ positive attitudes and mindset during the course. Moreover, the majority of students were able to complete the homework assignments, and everyone was able to participate in the tasks and projects, meeting Little’s requirements of “self-management” and “interaction with others,” (p. 2). Overall, it can be said that the course design and implementation provided the students with ample opportunities to become autonomous learners.

Conclusion

Overall, this research shows that the integration of the CCR’s framework when combined with task-based learning and project-based learning can be an effective way to design a course for non-English majors at the university level which promotes the development of autonomous English language learners capable of becoming 21st century learners who can be active members of their local and global communities. In closing, it must be noted that this is based on practitioner research and action research that was carried out for the first time. In order to make more concrete conclusions, this should be considered as a case study, and the research should be implemented again the following academic year to confirm whether the results hold true in multiple cases. Additionally, the research was carried out in an EFL classroom; however, the framework was designed to be used in various settings and across curriculums, so applying the framework to English courses at different institutions, or to other courses, would strengthen the validity of the results. Despite these limitations, the framework has proven to be effective for designing tasks that motivate students to actively use English in a classroom setting while expanding their knowledge of digital and informational literacy, developing the skills, character traits, and meta-learning abilities they need to succeed as learners in the 21st century.

Notes on the contributor

Adrianne Verla Uchida has been teaching English in Japan since 2004. She is currently an assistant professor at Nihon University in the College of International Relations. She received her MA TESOL from Teachers College, Columbia University in 2013. Her current academic interests include reflective practice and language learning psychology.

References

Beckett, G. H., & Miller, P. C. (Eds.). (2006). Project-based second and foreign language education. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Benson, P. (2013). Teaching and researching autonomy. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bergmann, J., & Sams, A. (2012). Flip your classroom: Reach every student in every class every day. Eugene, OR: International Society for Technology in Education.

Bergmann, J., & Sams, A. (2014). Flipped learning: Gateway to student engagement. Eugene, OR: International Society for Technology in Education.

Borg, S. (2016, October 19). Long live grammar teaching (or ‘It ain’t over till the fat lady sings’) [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://simon-borg.co.uk/long-live-grammar-teaching-or-it-aint-over-till-the-fat-lady-sings/

Borg, S. (2017, November 21). Why do teachers assess English the way they do? [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://simon-borg.co.uk/why-do-teachers-assess-english-the-way-they-do/

Bullsmith, C. (2019, March). A brief orientation to critical thinking and active learning in Japan. The CT Scan. Retrieved from https://www.dropbox.com/s/i4pe96ohxytk1t3/CT%20Scan%20-%20March%202019.pdf?dl=0

Burns, A. (2009). Action research in language teaching: A guide for practitioners. New York, NY: Routledge.

Dweck, C. (2017). Mindset—Changing the way you think to fulfil your potential. London, UK: Robinson.

Fadel, C., Bialik, M., & Trilling, B. (2015). Four-dimensional education: The competencies learners need to succeed. Boston, MA: Center for Curriculum Redesign.

Farrell, T. C. S. (2015). Promoting teacher reflection in second language education: A framework for TESOL professionals. New York, NY: Routledge.

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hihan. (n.d.) In Weblio. Retrieved from https://www.weblio.jp/content/%E6%89%B9%E5%88%A4

Hihan 2. (2017). In Imiwa? for Apple iOS (Version 4.1.2) [Mobile application software]. App Store. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/imiwa/id288499125

Holec, H. (1981). Autonomy and foreign language learning. Oxford, UK: Pergamon.

Kimura, D., & Tatsuno, M. (2017). Advancing 21st century competencies in Japan. Hong Kong, HK: Asia Society. Retrieved from https://asiasociety.org/files/21st-century-competencies-japan.pdf

Little, D. (2003). Learner autonomy in second/foreign language learning. In CIEL Language Support Network (Ed.). The guide to good practice for learning and teaching in languages, linguistics and area studies. Retrieved from https://www.llas.ac.uk/resources/gpg/1409

Little, D., Dam, L., & Legenhausen, L. (2017). Language learner autonomy: Theory, practice and research. Blue Ridge Summit, PA: Multilingual Matters.

Mann, S., & Walsh, S. (2017). Reflective practice in English language teaching. New York, NY: Routledge.

MEXT. (n.d.). The second basic plan for the promotion of education. [Pamphlet] Tokyo: Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology—Japan. Retrieved February 27, 2020 from https://www.mext.go.jp/en/policy/education/lawandplan/title01/detail01/1373795.htm

National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking. (1987). Defining critical thinking. Retrieved from https://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/766

Noels, K. (2013), Learning Japanese; Learning English: Promoting motivation through autonomy, competence and relatedness. In M. T. Apple, D. Da Silva, & T. Fellner (Eds.), Language learning motivation in Japan (pp. 15–34). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Nunan, D. (2004). Task-based language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

O’Leary, C. (2018). Qualitative research methods in second language learning: Review and evaluation. The Learner Development Journal, 2, 85–99. Retrieved from https://ldjournalsite.wordpress.com/issues/issue-two-qualitative-research-and-learner-development-2018/

Sekiguchi, T. (2017). Nihon no gakko kyoiku ni okeru kaku kyokato no manabi de ikusei kanno na konpitenshi no kankeisei [Relationships between competencies that can be fostered by studying in the Japanese education system]. Tokyo Gakugei University Journal, 69(1), 179–189. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/154817137.pdf

Snyder, B. (2019). Creating engagement and motivation in the Japanese university language classroom. In P. Wadden & C. C. Hale (Eds.), Teaching English at Japanese universities: A new handbook (pp. 137–143). London, UK: Routledge.

Swan, M., & Walter, C. (2011). Oxford English grammar course: Intermediate. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Verla Uchida, A. (2019). Introducing elements of a four-dimensional education into an EFL Classroom. Learning Learning 26(2), 51–56. Retrieved from http://ld-sig.org/autumn-2019-26-2/

Wadden, P., & Hale, C. C. (Eds.). (2019). Teaching English at Japanese universities: A new handbook. New York, NY: Routledge.

Williams, M., Mercer, S., & Ryan, S. (2015). Exploring psychology in language learning and teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Thanks for your paper and introducing (to me anyway) the CCR framework. Basing what may be a dry and uninteresting text based course, flipping it and introducing a communicative element aimed at producing forward and outward-looking autonomous students, making the class more active and communicative, is an admirable approach. Have them thinking about why they are learning a foreign language, and what insights on the world around them it might provide, should produce students who are independent of thought with a sense of responsibility for their own learning.

Perhaps for the next stage of the research, you could think about informing them of your intentions at the start? Be explicit about the skills and knowledge you want them to gain? It might make it easier for them to reflect if they know what standard they have to measure themselves against, and give them something to aspire to. You can ask them what do they want to get from taking the course, and does it match with the framework?

It might be good to think of this project as a pilot for next time. It’s important to consider that approximately half the class did not take part in the study, so it’s difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Also, making the students plan and reflect on each activity is giving them responsibility for their own learning and therefore helps them achieve autonomy, but it might be useful for you to think of a model student for your class – what can an autonomous student who has finished your course do? What skills do they have, and how do they think? Having this will give you and them something to measure against, useful both in terms of data collection but also in terms of student growth.

Reflection and critical thinking are difficult, especially when they involve self-criticism. Some can naturally do it but many need training. Did you notice any kind of progression in their thinking from the start until the end of the course? I think your study and perhaps the class activities themselves would also benefit from more/deeper reflective activities. The examples given of critical thinking look only like surface-level reflection, for example “I need to improve my vocabulary,” “Presentations need a loud, clear voice”. Use reflective activities to think critically about the self. For students, they can use it to critique their personal learning styles and habits, to think about how they are achieving goals etc. In what sense does the student need to improve their vocabulary? What kind of vocabulary do they need? How do they think they could improve it? What resource could they use, and how could they practice what they learned? How will they know that they have improved? These are questions that the learner has to ask themselves, which reflection needs to prompt.

Some means to develop your post-task reflective activity for your study and your class would be useful, enabling students to think more deeply about what they are doing. Just asking them to record their thoughts means that most will probably just record surface-level impressions. Prompt them with questions in a follow-up activity. For example; “I’m annoyed about today’s presentation because I can’t say what I want to say”

The next thing the student needs to be asked for example is ‘why can’t you say what you want to say?’ It could be issues of confidence, a lack of preparation which could be caused by a lack of time management skills, a lack of vocabulary. Once the problem is identified, courses of action can be planned, and the student can learn to start asking the questions directly to themselves. As a result, the student can gain a good idea of their strengths and weaknesses (character), and knowledge of themselves as a learner (knowledge & character).

A useful way to measure and analyse reflections is with a scale such as Fleck & Fitzpatrick (2010), or Kato & Mynard’s ‘Learning Trajectory’ (2016). Again, this will make your conclusions more rigourous and help the students measure their progression and gain a more of a sense of autonomy and control over what they are doing.

Fleck, R., & Fitzpatrick, G. (2010). Reflecting on reflection: Framing a design landscape. OZCHI ’10: Proceedings of the 22nd Conference of the Computer-Human Interaction Special Interest Group of Australia on Computer-Human Interaction. November 2010. doi:10.1145/1952222.1952269

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

Thank you very much for reading through my long paper and offering some really good advice. I have considered explicitly teaching the terms and sharing the framework with them. Indeed I had planned to do that this term however with the move to online courses, that will have to wait until next academic year.

I really like the idea of a model student to use to answer the questions you posed – what can an autonomous student who has finished your course do? What skills do they have, and how do they think?

You mentioned that I should have my students reflect more deeply by teaching various techniques about reflection. A simple one would be follow up questions. I agree that it would be a great idea and I plan to do that the next time around. One major setback was the amount of space the students had to write in their reflection sheets. I think making a Google form and asking them to submit that would produce much deeper reflections. When I had the students write reflections freely after projects last year, I received deeper and richer data.

Finally you mentioned about measuring reflection and offered me two sources. I am not familiar with Fleck & Flitzpatrick but I will look it up. Coincidentally, I purchased the Kato & Mynard book last year and look forward to reading it and learning more about the topic in the future.

Thank you for introducing the CCR in such a way that shows how it’s broad-natured approach can be used to encompass so many of the potentially more restrictive terms of other frameworks, wherein some of the subtleties may be lost otherwise if one tries to limit them to specifics. Furthermore, your decision to flip a required text that could be considered to “negatively impact student motivation” into at-home review rather than in-class review has inspired me to reflect on how I might approach a similar administratively-required text, given the freedom to do so.

I would like to echo Neil’s comment about informing the students at the beginning of the course about the different skills and knowledge you are hoping that they develop throughout the course. It could go a long way to help them understand that the course you are presenting to them as “facilitator and coordinator,” considering that many might step into the classroom expecting to learn grammar in a more traditional way, which may in turn raise their affective filter if they feel their expectations aren’t being met. I would even go a step further and suggest that a sort of needs analysis could be done at the beginning of the course in order to determine how students rate their current understanding of their skills and knowledge levels. This may help them have a more concrete idea of how much they are growing throughout the semester and provide them with a physical record to compare their answers to after they complete the end-of-semester survey. Furthermore, I wonder if the end-of-semester survey would also be able to show not only if students felt that they were able to improve certain skills, but also to what extent? For example, a likert-scale for each skill along with a follow-up question that asks why they rated themselves in a certain manner could be used. This might help measure the effectiveness of the course in each skill, as perceived by students.

I was curious, did you respond to your students’ reflections throughout the course, or were these collected and reviewed only at the end of the course? Short notes or questions from the instructor in an ongoing (but asynchronous) dialogue with learners throughout the semester might help transform this tool into a powerful resource for students to develop their meta-learning skills, and thus lead them toward further autonomy. Thornton and Myard (2012) provide a good case study of how this can be done in writing to engage with students in writing. Their analysis of metacognitive, cognitive, and affective foci in particular could provide insight into how to prompt students to “go deeper” in their reflections. I’ve provided the citation to their paper at the end of this comment.

Your paper was also able to clearly explain a problem with language that has been a challenge for multiple instructors, and I applaud your outlining the issue of students’ understanding of “critical thinking”. I’ve taught several sections of a course that was designed around the concept of developing critical thinking skills at a Japanese university and have run into the same issue of critical thinking being interpreted by students as the idea of finding fault with something rather than analyzing or observing input. I do wonder if students in this context might be better served if we instructors would limit our usage of this term or present another term that may be less difficult to misconstrue. I don’t have the answer, but this might be a great avenue to pursue in the future.

I’m certainly interested in reading about how any follow-up studies may result in noticeable patterns or identify areas of CCR implementation that may need focus for improvement in EFL courses. I genuinely hope that this is just the first of multiple case studies and look forward to deepening my own understanding of this four-dimensional framework. Thank you very much for sharing your inspired work!

Thornton, K. and Mynard, J. (2012). Investigating the Focus of Advisor Comments in a Written Advising Dialogue. in C. Ludwig and J. Mynard (Eds.) Autonomy in language learning: Advising in action. Canterbury, Kent: IATEFL. pp. 137 – 153.

Thank you very much for the feedback regarding my paper. I truly appreciate it.

If I were to run the class again in the future, I too think it would be beneficial to discuss with the students about the framework. I agree that it would strengthen my roles as coordinator and facilitator and give the students some direction.

Regarding the needs analysis, the second time I ran the course, I did indeed do just that. I have yet to analyze the data due to being away on maternity and childcare leave immediately after the semester concluded, but I look forward to seeing how the students answered at the beginning of the term versus the conclusion of it now that I am back to work. Knowing that others are giving me the same advice lets me know I am on the right path.

The feedback the students received on their class reflection sheets and the project reflections, all had followup questions from me, but few students took the initiative to deepen the dialogue and respond to my comments. Though they did write that reading my comments made them happy. Going forward, I think it would be great to further the conversation between the students and I, but I also worry about how practical it would be time wise. I think it would depend on their and my workload and maybe more class time would need to be allotted to the students to do this. It is definitely something to think more about.

Thank you again for your feedback. I greatly appreciate it.