Katherine Thornton, Otemon Gakuin University

Thornton, K. (2020). The effects of an incentive programme on SALC service engagement and long-term intrinsic motivation. Relay Journal 3(2), 150-172. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/030202

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

Self-access language centres (SALCs) provide vital support for learner autonomy and language learning, but can struggle to attract students whose attention is divided between classes, assignments, clubs and societies, and paid work. While interested in using the facilities to improve their language skills, students may feel intimidated by an unfamiliar environment populated by people they perceive to be more confident or proficient in foreign languages than themselves, and confused about the services on offer and how to access them. To encourage these students, many self-access learning centres (SALCs) offer incentive programmes or reward schemes such as stamp cards for using the self-access facilities. These incentives can even be tied to class grades, effectively being a required element of the curriculum. This study investigates the effect of one such self-access incentive scheme through the lens of cognitive evaluation theory, a mini-theory from within self-determination theory, which addresses the role of rewards on intrinsic motivation to learn (Deci & Ryan, 2017). At one institution in Japan with a small SALC, an incentive scheme called the passport was introduced for first year students studying English as their major. Over three years, a differing level of incentive was offered, linked to student grades for a compulsory class. Data on service uptake in both the years students were offered the incentive and the following year are used to investigate the effect of introducing the incentives, and survey data from students provide some insights into their attitudes to using the passport.

Keywords: intrinsic motivation, incentives, self-access, cognitive evaluation theory

Self-access language centres (SALCs) provide vital support for learner autonomy and language learning, but can struggle to attract students whose attention is divided between classes, assignments, clubs and societies, and paid work. While some SALCs may be linked to academic programmes which require students to spend a certain amount of time using the facilities, or complete specific activities, others offer their services on a purely voluntary basis. In this case, they must rely on advertising their services across the institution in different ways to encourage student use, such as orientations, teacher recommendations, posters around campus and social media activities. One approach which may be used to attract students is the introduction of an incentive programme, whereby students receive some kind of reward for using SALC services or facilities, such as tangible gifts like stationary or even vouchers with monetary value, or credit for their academic classes. It is hoped that these reward schemes encourage students who may otherwise not to visit the self-access facilities and engage in some activities there. Once through the door, students may overcome their hesitation, understand the benefits of using the facilities and even become regular users, having made an informed choice to engage with self-access learning.

There is a danger, however, that by providing a reward for SALC use, initial intrinsic interest and motivation is displaced by an external pressure, resulting in activities being fulfilled mainly or purely to get the reward. Deci et al. (1999) warn that “although rewards can control people’s behavior—indeed, that is presumably why they are so widely advocated—the primary negative effect of rewards is that they tend to forestall self-regulation. In other words, reward contingencies undermine people’s taking responsibility for motivating or regulating themselves” (p. 659). This is a particular worry for self-access learning practitioners, whose aim is to foster autonomy in learners. This paper aims to determine the effect of a stamp card incentive programme, named the passport, introduced to first year university students studying English as their major on service take up and student attitudes to using the services at a medium-sized SALC in Japan. Stamps for the passport were earned by participating in group or individual conversation sessions, advising sessions and workshops. For each SALC activity and post-activity reflection completed, students were awarded one passport point which contributed to their class grade, for a maximum of 10 points per semester

This paper first discusses the research on rewards and motivation, drawing on cognitive evaluation theory (CET) (Deci, 1972), a mini-theory within the larger field of self-determination theory (SDT) (Deci & Ryan, 2017), and studies in behavioural economics. It then describes the context of the SALC at the institution where the research took place and the details of the incentive scheme. Data from service usage records both during and after the period students are enrolled in the incentive programmes are examined to address the following research questions: 1) the effect of the passport on SALC service update for the cohort of students who receive the passport, and 2) the impact on engagement with SALC services of different levels of incentive after the incentive is removed, in other words the effect of the incentive programme on students’ long-term willingness to engage in self-access activities. Qualitative data from student questionnaires are also used to shed further light on these findings. The paper concludes with suggestions for designing effective incentive schemes in SALCs, and possible directions for future research.

The Role of Incentives and Rewards in Motivation and Behaviour Change

Cognitive evaluation theory and rewards

The passport is essentially a way of rewarding certain desired behaviour, in this case, using the SALC. Edward Deci was the first person to look in detail at the effect of rewards on motivation (Deci, 1971, 1972). He developed Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET), which later got subsumed into the bigger motivational theory of Self Determination Theory (SDT) developed with Richard Ryan (Deci & Ryan, 1985; 2017). This theory posits that human beings need to feel autonomy, competence and, to a certain degree, relatedness, in order to sustain intrinsic motivation to complete a task or action. CET examines the effect that environmental factors, such as rewards and incentives can have on the locus of causality, the reason why an individual completes a task.

Building on the designations from Ryan et al. (1983), Deci et al. (1999) identified different categories of rewards, both tangible (monetary rewards, trophies, gifts, points etc.) and intangible rewards (positive feedback and praise) and their effects on intrinsic motivation. Extensive research into CET has shown that while positive feedback, as long as it is experienced as informational rather than controlling, can enhance intrinsic motivation, tangible rewards tend to undermine it, as the main reason to complete the task becomes the desire to get the reward, thus externalising the locus of causality (Deci & Ryan, 2017). In behavioural economics, this is known as crowding-out (Gneezy et al., 2011).

Deci et al. (1999) examined different kinds of tangible rewards. For the purposes of this study, the most relevant type they identified are task-contingent rewards, whereby a reward is given for completing a specific task (completion-contingent) for merely engaging in, but not necessarily completing a task (engagement-contingent) or for not only completing, but fulfilling certain criteria in a task (performance-contingent). Results of a comprehensive meta-analysis they carried out suggest that while all task-contingent rewards undermine intrinsic motivation, this is true to a lesser degree for performance-contingent rewards, as the feedback gained for achieving a certain level of performance works as an affirmation of competence, which offsets to a degree the controlling aspect of the reward. They concluded that, to be effective, rewards should be constructed to convey value on the activity (such as rewarding reading with free books) and enhance the learner’s sense of competence, rather than be experienced as controlling, which may undermine a learner’s autonomy (Deci et al., 1999).

Incentives in behavioural economics

Kim (2013) points out that the vast majority of studies in CET have been carried out in laboratory conditions, which are difficult to replicate in real world situations. Behavioural economics researchers have, however, conducted experiments on incentives in a variety of situations. Gneezy et al. (2011) offer an overview of research conducted into incentives for education, increasing contributions to public goods, and lifestyle changes, and conclude that incentives do have a role to play in promoting certain behaviour, but that careful attention must be paid into the way they are constructed and communicated.

Financial Incentives in fitness programmes. Some studies from behavioural economics focus on fitness programmes. Possibly the closest parallel to SALC use would be fitness gym use, where people engage in specific activity in a designated physical space with the aim of self-improvement. Both SALCs and gyms can be intimidating to newcomers. Falkner et al.’s (2019) report on a fitness programme in Canada which offered Air Miles Reward Miles for gym use, but targeted existing gym users. Their study showed no significant differences between incentivised and control groups, and did not investigate behaviour change when the incentive was removed. Pope and Harvey (2014) investigated the impact of offering monetary incentives to first-year US college students for attending the fitness centre in their first semester, and found that while paying students to attend did increase attendance at the gym, discontinuing the incentive dramatically reduced attendance in the following semester, to the same levels of the control group. Charness and Gneezy’s (2009) study which also offered payment for gym attendance did, however, find an improvement in overall attendance level, even after the incentive was removed, which was driven by students who had not previously been gym users developing a new habit. An unpublished paper replicating this study (Acland & Levy, 2010, cited in Gneezy et al., 2011, p. 205) had similar results and also found a significant social factor: participants in the study were much more likely to attend the gym if those in their friendship group were doing so. This points to the importance of social networks in influencing behaviour. These studies, however, all used financial incentives, which are likely to be experienced as a more powerful reward than a few points contributing to credit for one class among many, as in the case of the passport.

Extra credit reward schemes. Few motivation studies have looked directly at awarding credit as an incentive. On such study was conducted by Cooper and Jayatilaka (2006), who investigated how offering extra credit points influenced creativity in a group task in an experimental setting, and had findings consistent with CET. However, these participants were recruited especially for the one-off for the experiment, rather than being a certain cohort enrolled in a long-term programme, so only limited parallels can be drawn with the current study.

Stamp card incentives in self-access learning

Incentive systems at self-access centres have been documented in several previous studies. In several papers, researchers at Toyo Gakuen University (Talandis Jr et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2012) report on a long-term action research project which investigated different kinds of stamp card models, both voluntary, with bonus points, and as a 20 – 25% mandatory part of a course grade, all designed to boost engagement with learning outside the classroom, including engaging with the SALC at their institution, English Lounge. They reported higher levels of engagement in English Lounge activities when the stamp card was a mandatory part of the course grade, although some students failed to engage even when the project was mandatory. However, the effect on English Lounge participation once the incentive was removed was not researched.

Mayeda et al. (2016) describe a similar stamp card project designed to orient students to different aspects of their SALC, including advising sessions, the English Café conversation service, and activities and events, and to encourage them to undertake language learning activities outside class. 20% of the grade for a first-year speaking class was allotted for 10 activities, and completion rates for submitted cards (50% of cards were either not submitted to teachers, or not passed on from teachers to the researchers) showed a completion rate of over 90% in the three semesters examined by the study. Student reactions were largely positive. Records for English Café conversation attendance showed that the stamp card marginally increased the overall attendance at these sessions, and that this attendance rate was sustained even when the stamp card was no longer in use in the following semester. This suggests that the incentive had only a small effect on attendance.

This current study aims to examine participation both during and after the incentivised period in a more systematic way.

Record-keeping and reflection

One possible advantage of a stamp card style incentive system could be in its promotion of record-keeping and reflection. Record-keeping, through tools such as learning logs, is recognised as an important tool to facilitate reflection (Murphy, 2008), which is a key skill in becoming a successful self-directed learner. By making and keeping a physical record of SALC use in their passport, including a reflection, students could be encouraged to become not only regular, but also reflective users of the SALC facilities.

The Context

The incentive programme examined in this paper was introduced at a small SALC at a social sciences university in Japan. The institution has around 7000 students and its self-access learning centre was established in 2013. The SALC mission is to promote language learning and intercultural exchange, and foster learner autonomy. It is available for all students and staff across the university to use, and engagement with the SALC was entirely voluntary for all. Its programmes do not carry credit. It has only three full-time bilingual staff: a director/learning advisor, one teacher and one administrator. Students are also employed as interns, counter staff, and English conversation facilitators, and there is an active volunteer group who organise events and support users. It is an active social learning space with an established group of students who know each other well, and others who use its services more individually but also regularly. In the SALC students can take part in individual or group English conversation sessions, access materials for language learning, make friends with like-minded students and exchange students, and join language learning workshops and other events. Until 2019 when the opening of a new campus required the SALC to split its activities between two facilities, it usually attracted around 80 to 120 student users per day, and was regularly full to capacity at peak times, but this number of users is still a small minority of the student body. The results of a 2019 survey administered to first year students about their experiences with and attitudes to learning foreign languages, which had a response rate of around 25%, indicated that 77% at least knew of the centre on the new campus where all first years are based, and 60% expressed a desire to use it, but daily usage data show that very few are doing so actively.

As the SALC has no direct links to the formal curriculum, it finds itself somewhat isolated, and must rely on PR activities and informal connections between SALC staff and faculty to encourage students to use the facilities. It attempts to inform students of its services through orientations which take place in class (which have been taken up by some but not all faculties), information sessions run at the beginning of each semester that any student can join, and regular PR through posters and social media posts. However, the effects of these efforts have been limited, and other methods were sought to familiarise students with the SALC spaces and services.

In 2017, the university administration began to encourage more collaboration between the SALC and the International Liberal Arts (ILA) department whose students major in English. Given the small size of the SALC, it was considered impossible, and from the SALC management’s view undesirable, to introduce any formal requirement for all students to use the SALC services, but some kind of incentive programme for first year students, linked to one of their compulsory classes, was considered feasible. While the SALC management was cognizant of the drawbacks of incentives, as detailed in the previous section, it was decided that the potential benefits of encouraging students to become more familiar with the SALC would make these risks worth taking.

The following section describes the incentive introduced at this institution.

The Passport

The incentive decided upon was named the passport. It has run for three years since 2017. (Efforts to continue the passport in 2020 have so far been disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic). At the beginning of each semester, freshmen students are given a physical “passport”, an A5-sized card, like a stamp card, with spaces where they receive stamps every time they take part in certain SALC sessions run by teachers or student staff. Stamps are not given purely for using the facilities. Each stamp is worth one point. After each session they receive a paper Reflection Sheet which they must complete and submit to the SALC for the points to be registered. From a CET perspective, this can be regarded as a completion-contingent reward, as points were awarded for completing various activities in the SALC, but no evaluation was made of those activities (Deci et al., 1999).

Over the years, the incentives have been designed slightly differently. In 2017 and 2018 10 points were offered, but due to a lower number of exchange students who facilitate the group conversation sessions, only 6 points were offered in Spring 2019. This was increased to 10 in Fall 2019. In 2017 the points were counted as extra credit for students’ conversation class. In 2018 this was changed to being 10% of the basic grade, to determine if this made a difference to students’ motivation to use the SALC. In 2019, a return was made to the extra credit model.

Students were introduced to the passport by their classroom teachers, who received information about it from the SALC. In 2018 teachers were asked to play an orientation video in class, to guarantee that all students got the same information.

Methodology

It should be noted that the passport was not designed based on findings from CET research. Rather, this study retroactively examines the role of the passport through a CET lens, to determine whether the effects hypothesised by CET can indeed be observed in this context.

This study decided to investigate the following research questions.

Research questions

- What effect does the passport incentive have on SALC service uptake for first year ILA students?

- Once the incentive is removed, what are the differences in participation in SALC services between groups offered extra credit and those whose points were included in the final grade?

Data collection

A number of sources were used for data collection, providing both quantitative and qualitative data to address the research questions. In order to measure in impact of the incentive on engagement with SALC services, passport completion rate data are given, and session attendance data for the two most popular sessions are examined: group conversation sessions and individual English Practice sessions. Results of a questionnaires administered after Spring semester in 2019 was also used to investigate student attitudes to the passport, and provide a richer picture of student experiences.

Findings & Discussion

Passport Use

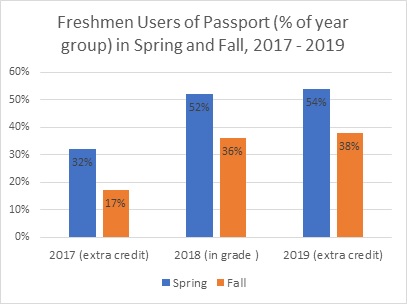

Figure 1 shows the rate of uptake of the passport over the last three years, as a proportion of the year group. Students who completed at least one activity were classified as having participated in the passport programme. Fall participation is consistently lower than Spring. This is in line with general usage of the SALC, which consistently records lower user numbers in Fall than Spring, especially among freshmen who tend to take more classes in Fall, and may be less eager to try new experiences such as visiting the SALC now they have settled into their university routines. Some studies into fitness programmes also show a significant attrition rate when a long break between semesters is present (Pope & Harvey, 2014).

While the chart shows that there was an increase in uptake when the incentive was strengthened from extra credit to being 10% of the grade, this increase was not lost the following year when it returned to being an extra credit system. It is noteworthy that even with the in-grade incentive in 2018, engagement with the passport programme never rose much above 50%, so around half of the students did not participate in SALC sessions, regardless of the incentive system.

Figure 1. Passport uptake, 2017 – 2019

Impact of passport incentive on SALC use (research question 1)

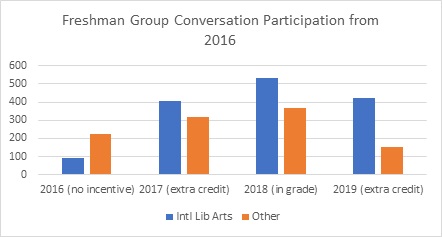

A number of data sources can help to illuminate the role the passport may have had on encouraging freshmen students from the ILA department to use the SALC. Figures 2 & 3 show the number of first year ILA students taking part in group conversation sessions and individual English Practice sessions from 2016 to 2019, and the total number of participating freshmen from other departments. Being English majors, ILA students made up a disproportionate amount of the total number of SALC users even before the passport was introduced, but both graphs show that the passport incentive has definitely had a positive impact on the participation of these English majors.

It should be noted that several changes took place in 2019, which may have affected the data in that year. Firstly, the university opened a new campus, on which the ILA department was now based. The SALC was given permission to run its activities in a new space on that campus, but there was no increase in staff, and rules forbidding paper posters made it more difficult to advertise SALC services. Secondly, there were fewer internationals students on campus that year to offer group conversation sessions. These changes resulted in fewer sessions being scheduled, so the decision was taken to limit the passport to 6 points in Spring, rather than the previous 10. In Fall, given that participation is usually lower that semester, 10 points were offered, as in previous years. This may have had an impact on the number of times students chose to join sessions, at least in Spring.

Figure 2. Freshmen group conversation participation, 2016 – 2019

In the case of group conversation sessions, while participation from ILA and non-ILA students both rose between 2016 and 2018 (and fell in 2019, possibly for the reasons stated above), ILA participation rose over 500% (from 95 to 534) in this time period. In contrast, while participation also increased significantly in the other departments, the rate of increase was less than 200% (from 222 to 370). ILA participation went from being 30% of total sessions in 2016 to over 50% in 2017 and 2018, and up to a huge 73% in 2019.

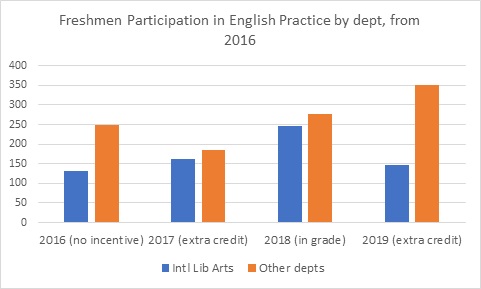

Figure 3. Participation in individual sessions (English Practice), 2016 – 2019

Participation in individual sessions, named English Practice, shows a similar trend. ILA participation rose from 131 sessions in 2016 before the incentive, to 161 and 245 in 2017 and 2018 respectively, when the passport was introduced. It is unclear why this number dropped again in 2019, to 146, but again this may be due in part to the changes in SALC services and the passport requirement described above. However, a similar fall is not seen in other departments.

From this data, it does seem that offering a stronger incentive (passport points being 10% of the course grade rather than just extra credit) may have had an impact on participation. The participation rate grew for both individual and group services between 2017 and 2018 when the stronger incentive was introduced, and fell again the next year when it was reduced to extra credit. However, looking at 2017 and 2018 data, overall participation of first years from other departments also grew for both services, albeit not at the same rate in the case of group conversation. More data are needed to be able to make this claim with any confidence.

Another factor in the rise in participation could be the support of teachers. Taylor et al. (2012) note the importance of collaboration between teachers and teacher encouragement and support of their stamp card being a key factor in student uptake, and Mayeda et al. (2016) identify a lack of teacher support for some classes as being a hindrance to the success of their incentive project. As the passport became more familiar to the teachers running the ILA courses, they may have been better able to encourage students to use it, resulting in the higher engagement rates seen in later years.

Effect of the passport incentive on long-term intrinsic motivation (research question 2)

While the passport may have achieved its initial aim of encouraging more first-year students to engage with SALC services than previously, for self-access researchers, it is also important to examine what the more long-term impact of the incentive may have been on students’ intrinsic motivation to engage in self-directed learning at the SALC. In order to investigate this, data from the same cohort of students in both their first year (when an incentive was offered) and their second year, when it was not, can be compared. For comparison, data for the other departments, for whom no incentive was offered in either year, are also given. (Data from one department, Global Japanese Studies, were removed from the data set due to the fact that a separate study abroad programme requiring SALC group conversation session participation was introduced in several years.) In these years, several small incentive programmes were offered to short-term study abroad students as part of their pre-departure programmes, but as these were small in number, attended by students in all departments, and impossible to remove from the overall data set, they have not been removed.

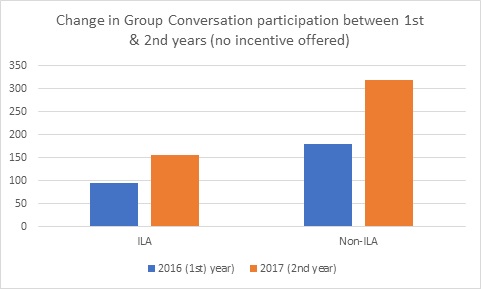

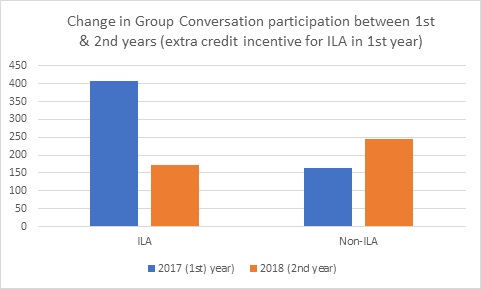

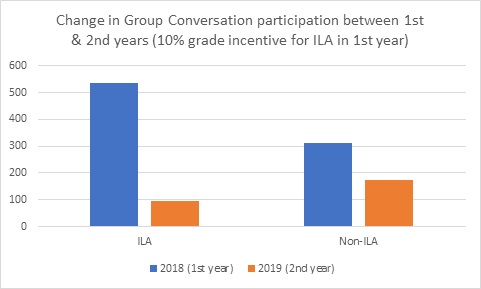

Group conversation participation. Figures 4, 5 and 6 show group conversation participation data from the same cohorts of students in both their first and second years. In Figure 4 there was no incentive offered to any student in either year, in Figure 5 an extra credit passport incentive had been offered to ILA students only in their first year, and in the following year, Figure 6, this incentive was raised to be 10% of the final grade for one compulsory course.

Figure 4. Group Conversation participation with no incentive (2016 & 2017)

For students who entered the university in 2016, when no incentive was offered to any students, group conversation participation rates grew in the second year for all students. The growth rate was 64% for ILA, but 79% for students from other departments. One reason for the likely increase is the overall increase in the number of sessions offered per week, as more exchange students were given facilitator duties in 2017 than in 2016, so students had more opportunities to join these sessions in 2017.

Figure 5. Group Conversation participation with extra credit incentive for ILA first years (2017 & 2018)

In contrast, in the following year, while participation from second years in the other departments continued to show an increase , albeit a smaller one (48%), participation from ILA students, who had been offered the passport incentive as extra credit in their first year, fell by 58% in their second year. It should be noted however, that a greater total of second year students joined the sessions in 2018 than in 2017 (172 in 2018, compared to 156 in 2017).

Figure 6. Group Conversation participation included in grade for ILA first years (2018 & 2019)

For the next year’s cohort, who entered the university in 2018, the difference between those receiving an incentive and those who did not is even more pronounced. Second year attendance fell in both groups, but the drop was more pronounced among ILA students, who had had the passport as 10% of a class grade in their first year. While non-ILA second year participation shows a drop of 45%, the drop for ILA students is a huge 82%, and the total number of sessions joined is also lower than the previous two years, at 97 (compared to 172 and 156 in the two previous years).

While it is true that these students’ second year, 2019, was a year of change, when the university opened the new campus, it is unlikely that these changes alone can account for the full extent of the drop in participation by second year ILA students.

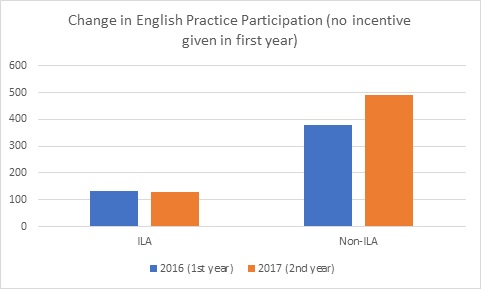

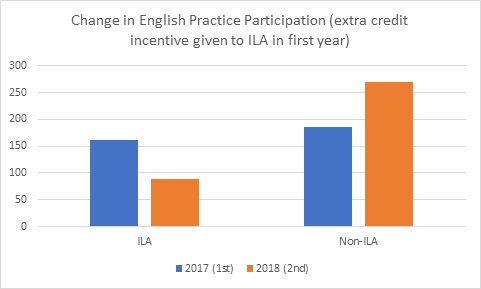

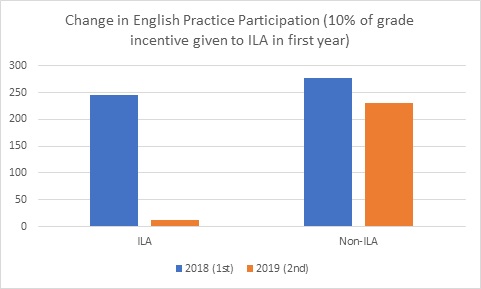

English Practice participation. A similar pattern is seen in the participation data for English Practice individual sessions (see Figures 7, 8 and 9 below).

Figure 7. Change in English Practice participation when no incentive was offered in the first year (2016 & 2017)

When no incentive was offered to any student in their first year, there was no noticeable change in participation rates between 2016 and 2017 for ILA students, whereas the number of participants from other departments showed a 29% increase in the second year.

Figure 8. Change in English Practice participation when an extra credit incentive was offered in the first year (2017 & 2018)

Figure 8 shows that in the following year, while the participation rate for other departments grew by 45% in their second year, the participation rate for ILA students who had received an extra credit incentive in their first year fell considerably (by the same 45% in fact) in the second year, when that incentive was no longer available.

Figure 9. Change in English Practice participation a 10% of grade incentive was offered in the first year (2017 & 2018)

Most strikingly, the next year, when English Practice session participation had been rewarded by up to 10 points of the final grade for one course in the first year, second year participation plunged by a huge 95% in the second year, to just 13 sessions from 245 the previous year. In contrast, while there was still a drop in participation from other departments with no incentive to participate, it was much lower (17%). This mirrors a similar trend in the group conversation data, reported above.

While more years of participation data are needed to confirm the trend, this seems to support previous CET research that task-contingent incentives have a negative impact on intrinsic motivation, and that once SALC participation had been framed as an activity which students engaged in to earn class points, this impression was sustained in the following year, resulting in fewer students accessing both the group conversation and the English Practice service. This effect seems to be more pronounced when the incentive was stronger (part of the grade) than when it was only offered as extra credit, suggesting that the offer of points did indeed crowd-out the intrinsic motivation for taking part in sessions, i.e. communicating in English or improving English communication skills.

ILA student attitudes to the passport

In Summer 2019, after one semester at the university, ILA first years were surveyed about their attitudes to the SALC in general and the passport in particular. In 2019 the passport operated under the extra credit system. 129 responses were received, of which 127 gave consent for their data to be used. This figure represents 81% of the freshman year in 2019.

Over half of students said they went to the SALC once a month or more, with a third visiting about once a week. This suggests that a significant minority of ILA students were starting to spend regular time in the space. However, nearly 20% stated that they’ve only ever been there during a class visit.

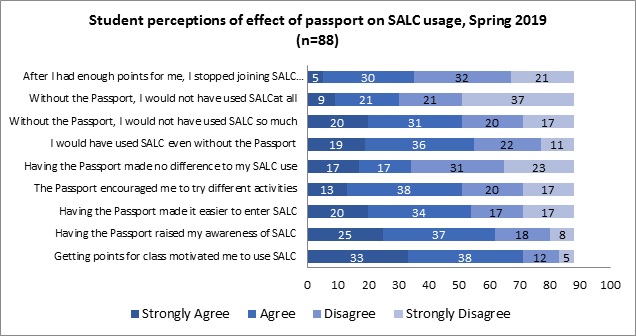

The study was interested in finding out what role the passport has played in students’ usage of the SALC. Respondents who used the passport (n=88) were asked the extent to which they agreed to a number of statements about the SALC and the passport (Figure 10). Over three-quarters of these agreed or strongly agreed that having the passport encouraged them to use E-CO and over 60% said it raised their awareness of the SALC and made it easier to enter the SALC, suggesting a positive effect of the incentive on habit formation. However, 40% agreed that they stopped joining SALC sessions after they had “enough” stamps (the survey didn’t specify how many was “enough”, so each respondent could interpret it in their own way). Over 50% said they would not have used the SALC so much without the passport, and 30% that they would not have used the SALC at all (although the number of students strongly agreeing with this statement is low – only 9).This suggests that over a third of students had low intrinsic motivation to use the SALC, and these students may have been helped by the passport. A higher percentage of students seem to have more intrinsic motivation to use the SALC, and deny that the passport had much effect on their behaviour. Nearly 40% of student agreed or strongly agreed that the passport made no difference to their SALC usage, and 60% claim they would have used the space even without it. Although this questionnaire data only provides student opinions, and therefore cannot be viewed as reliable, it does seem to suggest that for less intrinsically motivated students, the passport was effective in helping students become more familiar with the SALC and join sessions. Unfortunately, there is no usage data from 2020 to determine to what extent these students used the SALC after the incentive was no longer available.

Figure 10. Effect of passport on SALC usage

Both CET and behavioural economic theories emphasise that the way in which the recipient of the reward experiences it is key to understanding its impact. If the reward aspect is highly salient, it may replace or crowd-out any original intrinsic motivation to complete the task, thus externalising the locus of causality. Additionally, if the incentive is experienced as controlling, it may undermine the student’s autonomy (Deci & Ryan, 2017). In order to mitigate this, a reward must enhance competence, for instance by having a mechanism to provide positive feedback. Currently, although students complete a reflection after each activity, the volume of reflection sheets submitted has meant that it has not been possible to offer personal feedback to each student. Given the importance that the research places on such feedback, ways in which this could be done should be investigated. Encouraging reflection as part of the incentive programme, especially if this can be part of a reflective dialogue (Kato, 2012) with teachers or advisors, may also promote self-directed learning and result in a deeper engagement with SALC activities. In addition, the narrative around the Passport is important to help students maintain their intrinsic motivation. When the incentive is introduced, care must be taken to emphasise the benefits of participation in SALC services, rather than the reward itself. If the reward is less salient, research shows it is less likely to be experienced as controlling (Deci & Ryan, 2017).

One problematic aspect of the kind of reward programme detailed in this paper is its one-size-fits-all nature. To be fair to all, every student must be offered the same possible rewards, but each will start at the university with a different level of intrinsic motivation towards learning English in general and using the SALC in particular. While students with lower initial intrinsic motivation may benefit from the extra push that an incentive such as the Passport offers, and find they enjoy taking part in SALC sessions more than they expected, many others may already have been intending to become regular SALC users before the Passport was introduced to them. It is this group of students to whom the incentive is likely to be most detrimental. In a curriculum-wide project such as this, it is not possible to offer differential rewards to different groups. To counteract this effect, it is therefore necessary to create as positive an experience as possible for all users, in the hope that the SALC becomes a comfortable place where they wish to spend their time and engage in language learning activities, beyond the extrinsic rewards offered. This is where the third aspect of self-determination theory, relatedness, plays an important role. By interacting and even making friends with other users, or engaging with learning advisors and other staff, students who find themselves in the SALC initially to get a point for their class grade, may either develop or regain the intrinsic motivation to communicate in a foreign language and engage in self-directed learning. Findings from behavioural economics about the power of peer action in incentive programmes (Gneezy et al., 2011) also suggests that asking teachers to make time for class discussion on SALC activities could help less motivated students to realise that their peers are engaging in the SALC, and create a new norm that they are more motivated to achieve.

Conclusion

The findings from this study support the results from cognitive evaluation theory and behavioural economic studies that incentives can have a significant undermining effect on intrinsic motivation in the long-term, even if initial uptake is high. While the Passport did have a positive effect on engagement with SALC sessions, removal of the incentive resulted in a drastic reduction in the number of participants the following year, compared to students from the same department in previous years (assumed to have a roughly similar motivation levels) and students in other departments in the same year. This effect was stronger when the incentive was stronger (points included in the grade as opposed to extra credit). More research is needed to determine whether this finding is consistent over several years, as changes in the SALC environment (namely the opening of the new facility and a reduction in points offered in Spring 2019) may have played a role in student participation, which is a limitation of this study.

Further research could also investigate students’ initial attitudes to using the SALC prior to the introduction of the incentive, and try to determine whether the incentive has different effects on those with differing levels of initial intrinsic motivation. When introducing any kind of incentive programme, SALC practitioners should pay careful attention to the way it is structured and communicated to learners. Ideally, some form of reflection and an opportunity to get positive feedback should be incorporated to reduce the undermining effect of any reward offered.

Notes on the contributor

Katherine Thornton has an MA in TESOL from the University of Leeds, UK, and is associate professor at Otemon Gakuin University, Osaka, Japan where she works a learning advisor. She is the director of E-CO (English Café at Otemon), the university’s self-access centre, and a former president of the Japan Association of Self-Access Learning. Her research focuses on policy and practice in self-access language learning.

References

Charness, G. B., & Gneezy, U. (2009). Incentives to exercise. Econometrics, 77(3), 909–931. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA7416

Cooper, R. B., & Jayatilaka, B. (2006). Group creativity: The effects of extrinsic, intrinsic, and obligation motivations. Creativity Research Journal, 18(2), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj1802_3

Deci, E. L. (1972). The effects of contingent and noncontingent rewards and controls on intrinsic motivation. Organizational Behaviour and Human Performance, 8, 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(72)90047-5

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), 627–668. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.125.6.627

Faulkner, G., Dale, L. P., & Lau, E. (2019). Examining the use of loyalty point incentives to encourage health and fitness centre participation. Preventive Medicine Reports, 14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100831

Gneezy, U., Meier, S., & Rey-Biel, P. (2011). When and why incentives (don’t) work to modify behavior. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(4), 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.25.4.191

Kato, S. (2012). Professional development for learning advisors: Facilitating the intentional reflective dialogue. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3, 74–92. https://doi.org/10.37237/030106

Mayeda, A., MacKenzie, D., & Nuspliger, B. (2016). Integrating self-access centre components into core English classes. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(2), 220-233. https://doi.org/10.37237/070210

Murphy, L. (2008). Learning logs and strategy development for distance and other independent language learners. In S. Hurd & L. Murphy (Eds.) Language learning strategies in independent settings. pp 199-217. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847690999-013

Pope, L, & Harvey, J. (2014). The efficacy of incentives to motivate continued fitness-cener attendance in college first-year students: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American College Health, 62(2), 81-90. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2013.847840

Ryan, R., Mims, V., & Koestner, R. (1983). Relation of reward contingency and interpersonal context to intrinsic motivation: A review and test using cognitive evaluation theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 736-750. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.4.736

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2017). Self-determination theory. Basic psychological needs in motivation, development and wellness. The Guilford Press https://doi.org/10.1521/978.14625/28806

Talandis Jr., G., Taylor, C., Beck, D., Hardy, D., Murray, C., Omura, K., & Stout, M. (2011). The stamp of approval: Motivating students towards independent learning. The Toyo Gakuen Daigaku Kiyo [Bulletin of Toyo Gakuen University] 19, 165-182

Taylor, C., Beck, D., Hardy, D., Omura, K., Stout, M., & Talandis, G. (2012). Encouraging students to engage in learning outside the classroom. In K. Irie & A. Stewart (Eds.), Proceedings of the JALT Learner Development SIG Realizing Autonomy Conference, [Special issue] Learning Learning, 19(2), 31-45. http://ld-sig.org/LL/19two/taylor.pdf

As a long-time SALC co-ordinator in different universities around the world, I found this research paper highly interesting. I had never attempted to make the learning centre mandatory or for marks until Covid 19 struck and our centre here in Canada went fully online for the first time. We found very few students attended our Conversation Club now that it was online, whereas the club had been the highlight of student activity when the physical centre was open. In response, teachers now made attendance once a week at the club mandatory for grades (I believe no more than 10%). This has brought in students to some degree but, surprisingly, nowhere near the numbers expected. This indicates that students are willing to forgo 10% of their grade to avoid participating in the club. This may be attributed to the online environment and its effect on student engagement. This confirms the findings mentioned in your paper of Talandis Jr. et al. (2011) and Taylor et al. (2012) where even with a mandatory stamp card program, students failed to engage. I had thought, however, that those attending a mandatory program would want to continue attending on their own – without further incentive – in the years to come. Your findings surprised me in that way. This view is based on my time at my learning centres in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Here, classes would be brought to the centre by most teachers once a week to work on something language related. They could choose from a variety of activities including language learning games, movies, lectures, worksheets, books, magazines, and curriculum-related worksheets (changed every week to match the curriculum). It was mandatory in the sense that teachers decided to spend their class time in the centre and students had no choice but to participate. However, I observed that many students would come on their own time during the day to study or partake in an activity of their choice from these classes. It seems the act of bringing the students for class visits made them comfortable enough to come on their own. So, in my experience I would have expected different results from your study. In all three learning centres that I have run, the set up of the centre has played a critical role in student attendance as well. What draws them to the centre, or so they say, is how warm and welcoming it is. It would be interesting if you could describe the layout of the centre a little bit where this research took place – the colours, the furniture, the decoration, the different nooks and crannies for students to hide in and so on. For example, to make our learning centre in the UAE more culturally appropriate we had areas where we had majlis – these are sitting areas with large cushions on the floor. Here students could relax and read or even rest during the day. At my current centre in Canada, the décor is warm and welcoming and there are sofas and bean bag areas for students to lounge in. The centre has colourful indigenous art on the wall to welcome the students. I think the social aspect you mentioned in your research is also important. Recent research (currently awaiting publication) on our centre here in Canada confirms the importance of making new friends and spending time with old ones at the centre is high on the student list of motivators as well. Overall, your research has filled an important gap in the literature and will definitely guide my future activities at the centre. I thank you for your contribution.

Dear Dr. Hilda Freimuth,

Thank you for your comment on my paper, and your own insights from your experience both in Canada during the pandemic and in the UAE. That your experience echoes that of several previous incentive projects, and my own, in that a significant minority of students still do not engage with the SALC even with a percentage of their grade at stake, is both disappointing and reassuring to me, if that doesn’t sound too paradoxical. Disappointing, as it is always disappointing to realise that some students have no interest in engaging in activities and a space that we have taken great care to curate and design in a way to appeal to them and hopefully address their needs. Reassuring, in that this is further evidence that even offering a grade-related incentive does not seem to result in a large number of reluctant or resentful users who negatively affect the atmosphere of the space, and could put off more intrinsically motivated users. This has always been one worry of introducing an incentive that I have had, but I have not seen any evidence of it in my own observations. Those who really do not want to use the space will continue to ignore it, and while that saddens me, I accept that I cannot reach all learners, and am willing to focus my energies on those who do show at least some interest.

Thank you for your question about the space itself. I have similar evidence from user surveys here that students who do use the space find it welcoming and very comfortable. It has bright colours and different spaces designed for different activities – a sofa space for group conversation, watching DVDs and eating lunch, soft chairs in a quiet reading space, and individual study areas for more focused learning. It is often commented on as the most comfortable space on campus and different from other non-classroom areas such as the library. So I don’t think the space itself is off-putting to users, but there is some evidence that the feeling of not being part of a perceived “in-group” may affect whether someone feels truly comfortable there. I’m sure you’re familiar with the concept of legitimate peripheral participation from Lave and Wenger’s (1991) work on communities of practice. I think we need to work on helping these initially occasional users to see their participation in the space as more legitimate. Our student staff and regular users have an important role to play in this.

It is also nice to read that your experiences in the UAE show that when students do become familiar with a space due to initially being required to use it, they often continue to use it. I have seen this anecdotally over the years I have run my SALC, even if this data shows that it does not happen in the majority of the cases. I have also noticed that while many students no longer take part in the same services that the passport incentivized them to join, quite a number do still become regular users of the space itself, but use it more independently – to meet friends, talk to exchange students or learn autonomously with the materials available. Maybe it is the case that their usage of the space is maturing over time – something that cannot be measured by this limited quantitative study, but would definitely be worthy of investigation.

Thank you again for your thoughtful comments on my research. I am glad to start a discussion about the role incentives may have to play in orienting and socializing learners into using self-access spaces.

I think this study is a good example of how self-determination theory can be used as a critical lens through which we can gain a deeper understanding of language learners’ motivation for learning. By looking closely at the context you explore, and the ways you examine it with SDT’s cognitive evaluation theory can help others in similar self-access centres to identify what some of the factors might be, which either act as deterrents or attractors, to propel voluntary and sustainable use of the facilities and opportunities for language learning, be it though quiet study, or active participation with others there.

I enjoyed reading the paper very much as it’s a situation that most educators who have had experience in being involved in trying to promote the use of self-access facilities in language centres anywhere in the world can easily relate to. And, I appreciate the dedication and determination you have shown in taking a longitudinal approach to explore the effects of reward schemes on the attitudes and sustained initiative of the students who participated in this study. There is clearly a need for further research, but your initial findings are not only important because they would seem to corroborate previous research findings from CET applied studies, but also because they strengthen what has been discovered in previous explorations of self-access, which is that using reward systems to draw students to the centers may have a superficial and immediate effect on their motivation to go, but that this type of external control/incentive ultimately has a corrosive effect on autonomous, sustainable motivation.

The paper on the whole is engaging, informative, and draws attention to an essentially wide-ranging problem/conundrum that also needs to be addressed, namely the importance of students’ autonomous motivation and engagement, and how to facilitate the conditions/environment to enhance this, through autonomy-supportive behaviours, and affordances consciously and systematically conveyed through not only design support, but also through supportive communication between all those involved (students, teachers, advisors, administration, etc.).

There are however, a few areas in the paper which I would like to point out that you may want to look into further, with the aim of strengthening the paper even further. The first of these concerns the way you rely on intrinsic motivation as your main focus, referring to this as the type of motivation students have to come to the SALC, which is at risk when external awards/pressures/incentives are linked to encouraging use of the SALC. Intrinsically motivated behaviour in SDT is defined as volitional action, activities done for their own sake, because they are inherently interesting, fun, or for the joy which they produce (Ryan & Deci, 2020). But why then the need for an incentive programme in the first place, if students were intrinsically interested to use the SALC from the beginning? When you explain in your introduction that the aim of the incentive programme is because – “Once through the door, students may overcome their hesitation, understand the benefits of using the facilities and even become regular users, having made an informed choice to engage with self-access learning” – this seems to refer to the internalisation of extrinsic motivation (identified/ integrated regulation) rather than the intrinsic motivation that you make reference to in the following paragraph and elsewhere in the text.

For example, you come back to this when you discuss your second research question when pointing out the need to understand what impact the “incentive may have been on students’ intrinsic motivation to engage in self-directed learning at the SALC.” However, intrinsic motivation would suggest that students engaged in self-directed learning at the SALC out of interest, enjoyment and inherent satisfaction. But, by using an incentive to attract and encourage student engagement, would this not suggest instead that this is purposefully done to motivate students extrinsically, with the aim being that once they recognise the value of going to the SALC, they become regular users on their own accord? Identified and Integrated regulation are types of extrinsic motivation that also have an internal locus of causality, and when this type of regulation is internalised, they are part of what is called, autonomous motivation, which is different from controlled motivation.

The point of this lengthy example is that this may suggest that while looking at the effect of rewards to incentivise SALC participation through the lens of CET, what can also bring understanding to why some students who went because of the passport, eventually became regular users, would be better approached, perhaps, through Organismic Integration Theory, which focus on the different types of extrinsic motivation, and how it can be internalised and integrated to become, not intrinsic motivation (which is clearly different), but another form of powerful and sustainable autonomous motivation which is regulated internally.

In your brief review of CET you mention that basic psychological needs in SDT require support to “sustain intrinsic motivation to complete a task or action”. There is more to why the basic psychological needs are considered essential for full functioning. When they are supported they not only enhance autonomous forms of motivation, but also act as nutrients which intensify student engagement, learning, and well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2020). While you are focusing on a specific area of SDT (CET), it might be useful to further expand on what the full consequences of having these needs fulfilled or thwarted are in this paper, as this has a clear role to play in what you refer to in your conclusion as, the necessity “to create as positive an experience as possible for all users, in the hope that the SALC becomes a comfortable place where they wish to spend their time and engage in language learning activities, beyond the extrinsic rewards offered.

To end with, I would like to again reiterate the valuable contribution of this study to the field of self-access. The paper and the study are very well put together and has real potential to bring further clarity and understanding to how we can best bring students into the SALCs of the world while inspiring new insight into how we can sustain their motivation to return for their own sake, interest, and enjoyment by applying SDT and its other mini-theories to the field of self-access learning.

Dear Scott,

Thank you for your detailed response on my paper, and your thoughtful and very useful suggestions. I would like to respond to a few of the points you raise.

Firstly, about the reason for the incentive in the first place. There are several reasons for this, which I hope I have made clearer in my revised paper. The SALC was required to “integrate” with the curriculum of the international liberal arts faculty, and it was both very undesirable from my perspective as a supporter of autonomous and voluntary usage of the SALC, and logistically impossible with such a small SALC, to introduce some kind of programme where all students were required to use the SALC facilities – thank goodness! In this sense, the incentive was a compromise – students would be encouraged but not required to use the facilities through the carrot of a few points for one of their classes. You suggest that introducing an incentive such as this implies that potential learners are not intrinsically motivated to use the SALC. I would say that while this may well be the case for a proportion of the student body, there are many students, especially in this faculty whose major is English, who are intrinsically motivated, but still nervous or hesitant to use the facilities, as these are likely to be unfamiliar and possibly intimidating on first encounter. This reluctance to enter the space, despite a strong desire to use it, is well documented in SALC literature and I have added more reference to some of these studies in the paper. It was therefore hoped that one positive effect of an incentive would be to encourage both these groups of students (those with only extrinsic motivation, but also those who were more intrinsically motivated, if hesitant) to experience and grow familair with the SALC. I wanted to investigate which effect was larger, the danger of the detrimental effects suggested by cognitive evaluation theory on those intrinsically motivated students, or whether the incentive would indeed help more intrinsically motivated students overcome their initial intrepidation.

I’d like to thank you for your suggestion to also consider the role of extrinsic motivation more fully, and include organismic integration theory, another mini-theory of self-determination theory. My further reading into this mini-theory was very fruitful, and has helped me to articulate more fully the kinds of motivation different students may be experiencing, and how the incentive may have affected them. As I point out in the paper, one of the main problems with an incentive such as the one that has been implemented in my context is that it is rather a blunt tool, and cannot be adapted for different students who are motivated in different ways. Therefore, being able to examine the potential impact of the incentive from both these perspectives has been very useful, and I have broadened the research questions to consider both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, and included a review of the four kinds of regulation that Ryan and Connell (1989) identify in terms of extrinsic motivation. Unfortunately, while there is little evidence from my data that students did indeed experience more autonomous motivation as they became more familiar with the SALC, anecdotally I know this to be the case for at least some students. This has led me to consider the design of the study, and to recognise that in only examining participation in two very structured sessions I am interpreting SALC participation in a very narrow way. In future studies, if I am able to gather data on a wider range of SALC activities or more general SALC participation, and include a qualitative element, there may be more data to show that students initially extrinsically motivated by the incentive did indeed internalise their locus of causality as they came to value the SALC, and that this has led to more varied and more autonomous participation in all the things the SALC has to offer. That said, the current study has reinforced my desire to make sure that any future incentive is introduced in such as way as to not be experienced as controlling by the students, and ideally treated as part of an orientation to the space.

Thank you again for your insights. They have been very valuable and I appreciate you taking the time to share them with me.

Hi Katherine,

Thank you so much for doing this research and publishing it here. It is an important part of the story as we are always discussing ways to attract learners to SALCs. We know the benefits of using a SALC (and learners usually do, too!), but overcoming the various barriers that prevent SALC use is an ongoing struggle.

We introduced a ‘Linguistic risk taking passport’ project last year (see McDonald & Thompson, 2019) to help students to build confidence in using English inside and outside the classroom (including in the SALC and off campus), and to document their own learning. It was a research project with partners at the University of Ottawa in Canada (see Slavkov & Séror, 2019). We liked the project because it was optional and there was no credit, stamps, or external incentives; students chose and marked off their own tasks and document how they felt. Although 500 passports were collected by students, only 30 people turned them in at the end. However, from the 29 passports that were analysed, the results are encouraging in terms of the confidence and WTC that the participants felt seemingly as a result of the “push” that the passport gave them.

One thing that made me slightly uncomfortable was that in this pilot study, there was a prize draw at the end for everyone who completed at least 20 risks and handed in their passports (which included a record of activities, reflections, and also a short questionnaire). Mainly we offered this prize to replicate what our research partners were doing in Canada, but we tried to separate the prize (which was for participating in the research) from the passport activities as we were encouraging students to do for internally-controlled reasons rather than an external reward, but it is hard to communicate the distinction. We decided that we’ll probably drop the prize next time (or make it something nominal like a few 500 yen book tokens) as it didn’t actually result in many people dropping off their passports anyway.

Thank you again for doing this research and helping us to understand SALCs from an SDT perspective which I think has huge potential for the future.

Best wishes,

Jo

Just in case you didn’t see it, I am pasting a small section below of a chapter that I published last year where I advocate SALC use being voluntary but heavily encouraged.

References

MacDonald, E., & Thompson, N. (2019). The adaptation of a linguistic risk-taking passport initiative: A summary of a research project in progress. Relay Journal, 2(2), 415-436. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020216

Slavkov, N., & Séror, J. (2019). The development of the linguistic risk-taking initiative at the University of Ottawa. Canadian Modern Language Review, 75(3), 254-272. doi:10.3138/cmlr.2018-0202

Chapter extract.

Source:

Mynard, J. (2019). Self-access learning and advising: Promoting language learner autonomy beyond the classroom. In H. Reinders, S. Ryan, & S. Nakamura (Eds.), Innovation in language teaching and learning: The case of Japan (pp. 185-210). Palgrave Macmillan.

Example 4. Advocating Voluntary SALC Participation (p. 200)

The issue of whether or not self-access participation should be optional or required has not been fully resolved (Thornton, 2016). Many colleagues in Japan maintain that optional use of a SALC is key (Bibby et al., 2016; Cooker, 2010). The exception to this rule tends to be for compulsory orientation activities. In order to encourage rather than enforce SALC usage, some institutions have: (1) introduced activities in class that may ideally be completed in a SALC (e.g., Thompson & Atkinson, 2010), but where students might still make that active choice; (2) enrolled learners in extensive reading programs where the materials are available in the SALC, thus creating a ‘need’ and opportunity for students to engage in self-access learning in other ways (e.g., Shibata, 2016); and (3) provided homework assignments such as interview tasks that require students talk to other people in the target language. As other target language users can often be found in a SALC, it may be the perfect location for completing such assignments (Croker & Ashurova, 2012). Some projects in Japan have incentivized SALC attendance through class grades or stamp cards (e.g. Mayeda et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2012). However, this might not be a suitable approach for all institutions, and caution is advised. As we know from the self-determination theory (e.g., Ryan & Deci, 2000), rewarding something that was previously motivating for its own sake can undermine the original intrinsic motivation once the reward is removed. In the case of Mayeda et al. (2016), there was only a moderate increase in uptake after the introduction of stamp cards. In the study by Taylor et al. (2012), SALC participation increased dramatically when the stamp cards were used but dropped again when the students were no longer required to use the system.

Lessons learned: The degree to which encouragement, requirement or incentives are appropriate will depend upon the context, but for self-access to truly promote autonomy, students should be able to make the choice about whether to use a SALC for themselves (Cooker, 2010).

References

Bibby, S., Jolley, K., & Shiobara, F. (2016). Increasing attendance in a self-access language lounge. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(3), 301-311. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep16/bibby_jolley_shiobara/

Cooker, L. (2010). Some self-access principles. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(1), 5-9. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/jun10/cooker/

Croker, R., & Ashurova, U. (2012). Scaffolding students’ initial self-access language centre experiences. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(3), 237-253. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep12/croker_ashurova/

Mayeda, A., MacKenzie, D., & Nusplinger, B. (2016). Integrating self-access centre components into core English classes. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(2), 220-233. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/jun16/mayeda_mackenzie_nusplinger/

Shibata, S. (2016). Extensive reading as the first step to using the SALC: The acclimation period for developing a community of language learners. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(3), 312-321. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep16/shibata/

Taylor, C., Beck, D., Hardy, D., Omura, K., Stout, M., & Takandis, G. J. (2012). Encouraging students to engage in learning outside the classroom. In K. Irie & A. Steward (Eds.), Learner Development SIG Realizing Autonomy Conference Proceedings. [Special issue] Learning Learning, 19(2), 31-45. Retrieved from http://ld-sig.org/LL/19two/taylor.pdf

Thompson, G., & Atkinson, L. (2010). Integrating self-access into the curriculum: Our experience. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(1), 47-58. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/jun10/thompson_atkinson/

Thornton, K. (2016). Promoting engagement with language learning spaces: how to attract users and create a community of practice. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(3), 297-300. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep16/thornton/

Hi Jo,

Thank you for your comment on my paper, and the information about the risk-taking passport project. I have heard a little about this project before, and have even discussed something similar, but not restricted to language learning, at my own institution. My faculty organises an orientation programme for incoming first years, which is largely peer-led, and I wondered whether a similar project would be a good way to encourage students to explore the various possibilities open to them at the university, not only our SALC but various extra-curricular programmes that can do a great deal to enhance their university experience. I hope I may be in the position to implement something like this in the future, so yours and other studies into this risk-taking passport will be invaluable.

It is interesting that, in your project, the external reward offered does not seem to have had much effect, in terms of encouraging completion of the risk-taking passport project, but I wonder if it factored into whether students picked up a passport in the first place. If the students then enjoyed the activities they engaged in, the promise of a prize may become less important than they initially felt it to be. In this way, the incentive could have some valuable effect on initial engagement, but with few detrimental long-term effects. But this is merely conjecture…without asking students there is no way of knowing!

I didn’t write about it in this paper but we also have a small stamp card that students can complete by taking part in SALC activities, but on completion they only receive a pen. This is such a small reward for the effort of joining so many activities, so I do not think of it as a strong incentive. Anecdotally it does seem to me that just the fact of getting the stamp, maybe as a recognition of their achievement in taking part in an activity (therefore in CET terms a completion-contingent reward), does encourage intrinsically motivated students to feel valued in the SALC, and help them to keep on coming back. While you may say (and Scott does, above!) that if they are truly intrinsically motivated, this would not be necessary, we all know how easily a student’s best intentions to use a SALC can be disrupted by changes to their routine or othr factors, so this stamp may give them that extra positive reinforcement for their actions in the early stages of their SALC journeys. These students often discontinue using the stamp card after completing one, but keep taking part in conversation sessions as they enjoy them and recognise the value to their learning.

I completely concur that SALC use should be “voluntary but heavily encouraged”. While I do worry about the long-term effect of incentives on students, I don’t see having this small incentive programme as contradicting that belief, especially when it is only offered as extra credit, and therefore, an encouragement (my preferred design, and one that luckily the professor in charge of the project in that faculty agrees with). In the current research, it is impossible to know how those students would have used the SALC without the incentive. Those who used it a few times and then never used the SALC again after the incentive was withdrawn may otherwise have been non-users, in which case there has been no big damage to their motivation. As I commented to Dr Friemuth above, the fact that really reluctant users refuse to engage at all goes some way to reassure me that there is little danger of the supportive atmosphere of the SALC being damaged by an overwhelming presence of unmotivated users. My main concern is for those who did have the intrinsic motivation to use the SALC on entering the university, and may have been negatively affected by the passport project, as the results of this and previous research suggest may have happened. However, I currently have no way to identify those students, or know how many of them there are. In this way, I feel the incentive is somewhat of a blunt instrument, and its potential damage comes in that it has to be applied across the board to all students in the year group, regardless of their initial levels of intrinsic motivation.

Currently, the passport is part of the SALC’s requirement to collaborate more with faculty, so while this requirement exists I will do my best to maximise the potential benefits it may have to encourage more students to engage with our facilities, and get over their initial hesitation (or even fear!), while trying to mitigate any negative impact on student motivation through providing a positive experience and downplaying the role of the incentive itself. We do this currently by explicitly describing the passport as a way to try out different SALC services and discover what the space has to offer, and hope that students perceive it in this way.

Once again, thank you for engaging with my research, and I’m glad I could contribute even a small piece of the puzzle to our ongoing attempt to understand how to make SALCs attractive and meaningful spaces for students to engage in language learning.