Gamze Guven-Yalcin, Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University

Rukiye Buse Kayaalp, Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University

Selin Doğan, Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University

Betül Öztürk, Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University

Emir Şamil Doğan, Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University

Ayşenur Neşeli, Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University

Ömer Faruk Acar, Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University

Guven-Yalcin, G., Kayaalp, R. B., Doğan, S., Öztürk, B., Doğan, E. Ş., Neşeli, A. & Acar, Ö. F., (2022). A Message to the Advisor-Self: Fostering Autonomy Through Exploring the Identity Within Agentic Engagement. Relay Journal, 5(2), 68-86. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/050202

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

Learners are likely to grow autonomous through understanding causal relations and recognizing self-agentic responsibilities (Bandura, 2006). Once they are provided with an autonomy-supportive learning environment, they engage with one another in a purposive and proactive way, which may be referred to as agentic engagement. To this end, the focus of this paper is on the reflections of six peer advisors (PAs) at a medium-sized public Turkish university as they explored prominent characteristics of their advisor identity, with reference to the end-of-training appreciation cards that were presented by their advisor educators. Based on Benson’s contribution (2007) to the field illustrating the “interwoven” relationship of identity formation and autonomy development (p. 30), PAs’ reflections on their identity are observed to lead to the exercising of agency, which fulfills the basic psychological need of increased autonomy. This paper explores the interrelatedness of the key constructs of autonomy, agency, and identity in language education and is intended to meet the need for empirical knowledge relating to these three major concepts (Benson, 2007; Huang & Benson, 2013) by providing some evidence examining their relationship within the peer advisor education setting.

Keywords: autonomy, agentic engagement, identity, peer advisor education

There exists a need to explore the conceptualisation of and interaction between autonomy and other “learner-focused constructs,” (Benson, 2007, p. 34), i.e., agency and identity, within specific contexts. Accordingly, the aim of this paper is to examine perspectives on peer advisor (PA) development with a focus on their improved level of autonomy through the advisors’ co-constructive reflections on their individual identities within an agentically engaging activity.

The first part of the paper gives theoretical perspectives of the three key constructs of engagement, agency, and identity, followed by an overview of the Peer Advisor Education (PAE) program at Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University School of Foreign Languages (AYBU-SFL), as well as its methodology and educational implications. The subsequent part displays the PAs’ reflections on end-of-course appreciation cards, and the final part focuses on the impacts of this reflective practice on the PAs’ identity development.

Background

Engagement influences motivation and behaviour, and it can be categorized into four varieties: behavioural, emotional, cognitive, and agentic engagement (Reeve & Tseng, 2011). Agentic engagement refers to learners’ enriching the learning activity rather than passively receiving it as given. It is critical to understand these areas of engagement, how learners engage in these areas, and how they integrate themselves into learning environments in order to create the conditions for agentic learning (Reeve & Tseng, 2011).

Along with engagement, the basic psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness, and competence are cited in self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985) as contributing to the development of student agency. Meeting those needs of the learners is possible not only by developing positive educator-learner (educator relatedness) and learner-learner relationships (peer relatedness), but also by giving learners perceived choice over their own actions (autonomy). In addition, matching the level of difficulty to the skill level of learners meets the need of competence by increasing learner confidence.

Agency was defined by Bandura as “the power to originate action” (2001, p. 3). The recognition of this power leads to the agency from action causality to personal causality through “the differentiation of [the self] from others” in Bandura’s terms (2006, p. 169). This differentiation is possible when learners are provided with an autonomy-supportive learning environment to let them initiate a purposive, proactive, and reciprocal type of engagement, i.e., agentic engagement. Agentic learning, in this sense, involves assessing, energizing, and supporting the motivational satisfaction of learners, which all relate to the outcomes of the pilot training in the PAE program.

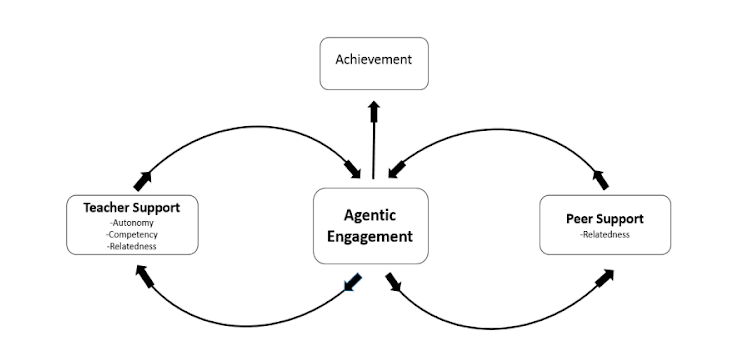

Agentic engagement is a learner-initiated path that makes learning activities (and more broadly, the learning environment) more motivationally helpful while also enhancing one’s learning, growth, and performance. Learners who are reciprocally and agentically engaged look for educator-learner interaction patterns that include reciprocal causality. In the framework of agentic engagement by Wakefield (2016), illustrated below in Figure 1, learners try to collaborate with educators and their peers to establish a more motivationally supportive learning environment as well as educator-learner and learner-learner relationships. This helps them create needs-satisfying, interest-relevant, and personally valued learning experiences.

Through agentic engagement, learners self-generate deliberate action to proactively engage in environmental interactions in ways that increase the likelihood of need-satisfying experiences. As suggested by Reeve and Shin (2020), facilitation of learners’ inner motivational needs helps them to get involved in the learning process by interacting with their educators and their peers. In other words, the perceived support from social partners and educators reflects learner engagement in the learning environment, as suggested by Reeve (2012). The reciprocity in agentic engagement is seen in the concept model of the reciprocal process by Wakefield (2016, p. 9; see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The concept model of the reciprocal process. From “Agentic Engagement, Teacher Support, and Classmate Relatedness—A Reciprocal Path to Student Achievement” by C. R. Wakefield, 2016, UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones, 2757, p. 9. Copyright 2016 by Curt Ryan Wakefield.

Identity, the concept of the self in Taylor’s terms (1989), is formed and developed through learning, as identity development is based on the recognition of learners’ own committed beliefs, goals, and values. It is about recognizing one’s own consistency over time and allowing others to recognize that consistency (Erikson, 1980). Erikson’s suggestion corresponds with Hawkins’ (2005) definition of identity formation as the co-construction of the views of the self and the world. The nature of identity, which is described as “multiple, changing, contradictory, elusive, and fragmentary” by Huang and Benson (2013, p. 18), can be seen as transformative and transformational, as it can be co-constructed and negotiated through language and discourse within a specific context. Within the context of PAE, it is within transformational advising (Kato & Mynard, 2016) that the learner’s preexisting ideas are challenged in order to increase learning awareness, turn that knowledge into action, and ultimately transform learning fundamentally.

Developing the capacity for sustained and self-regulated autonomy is central to advising in language learning (ALL), which integrates several theories, including Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory (1978), Mezirow’s transformation theory (2009), and constructivism. In this regard, advisor education is based on helping learners (including advisors themselves) learn to reframe problematic sets of assumptions that they have in their learning (e.g., the belief that learning advisors give direct advice or that qualities such as perfectionism are fixed, unchangeable traits). Such assumptions are problematic as learners may miss out on the individual differences in learning. Accordingly, advisor education helps learners to become “more inclusive, reflective, open, and emotionally able to change,” as asserted by Cranton (2006, p. 268). This transformative learning develops the cognition of learners (advisors in this context) in relation to the interaction between their experiences and ideas. Similarly, based on Kato’s (2012) intentional reflective dialogue as the core methodology, the PAE program at AYBU-SFL is aimed at helping learners gain the skills and perspective to be able to manage their own learning and the agency to help other learners manage their learning in an autonomy-supportive and collaborative learning community.

The Context: Peer Advisor Education

The Peer Advisor Education training was piloted as an extracurricular training course for volunteering PA candidates during the 2021–2022 academic year. With the intention of sustaining its positive outcomes, it was developed into an elective course titled Advising in Language Learning in the following year. Since the 2022–2023 academic year, it has been offered as an elective course for first- to fourth-year students in all departments of the institution.

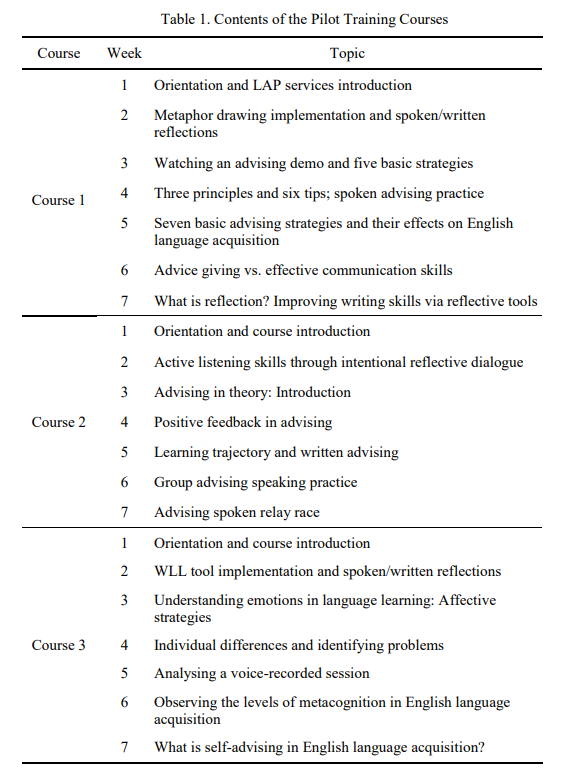

The pilot training was comprised of three 7-week modules covering the core topics of advising skills, approaches, and tools for conducting reflective dialogues. Table 1 contains a summary of the schedule.

The overarching objectives of the course were to equip trainees with the necessary skills and perspective to conduct face-to-face peer advising services and to launch a brand new digital advising service together. Mock-advising sessions were held to ensure that trainees had plenty of chances to put the skills and strategies they had learnt to use. Within the process assessment of each module, the practice-oriented assignments were interwoven with the theoretical underpinnings learned in the lessons and the readings. The assessment framework was based on the exchange of synchronous and asynchronous critical reflection on practice, on the reading assignments, and on peer feedback.

During the PAE pilot training, the advisor educators of the course, Gamze Guven-Yalcin and Stephanie Lea Howard, informed by SDT (Deci & Ryan, 1985), preferred to communicate with the PAs through specific autonomy-supportive instructional behaviours. For example, they initially conducted guided discussions with the PAs in order to exchange perspectives about the objectives of the lessons. In addition, they involved the trainees in the learning activities by letting them choose the type of activity during the lessons, and they provided explanatory rationales behind the activities. They also created opportunities for learner input and encouraged PAs’ initiative in designing a digital platform to share their reflections and engage with each other. During the training, the educators relied on invitational language and acknowledged and accepted expressions of negative affect when needed. They also offered learning activities in need-satisfying ways and set the lesson hours at trainees’ preferred times. Behaviours such as these have demonstrated positive outcomes promoting agency in studies such as Matos et al. (2018) and Reeve et al. (2020). Transparently teaching the expectations and guiding principles of agentic learning helps learners collaborate with their educators, using their agency to make things happen through their own actions. In the following sections, we present examples of those developments in the agency of the PAs.

PA Cards and Reflections

Giving thank-you and appreciation cards to course participants was initiated by Satoko Kato and Jo Mynard during the advisor training they conducted at Kanda University of International Studies, Japan, in 2017 and made into a tradition by Gamze Guven-Yalcin and Stephanie Lea Howard in the following advisor education trainings at AYBU-SFL (Karaaslan et al., 2019). The choice of the representative keywords is based on the educators’ observations of the trainees during their training programs. One goal of these cards is to highlight the strengths of the advisor candidates. If the process is considered in terms of BPN theory, the program participants were expected to more deeply reflect on their advisor selves and discover their strengths as advisors, which in turn promotes their sense of competence. In addition, as the reflection cycle is initiated by their faculty mentors (i.e., the trainers), it refers to a type of support fulfilling the need for relatedness. Also, this fulfillment of the feeling of relatedness triggers a reflective process, and PAs then wish to reflect on those cards. Therefore, the whole process provides an improvement in their choice of actions, which may promote autonomy. The exchange of reflections by the PAs, along with the appreciation cards, sets a nice example of fulfilling their inner motivational needs within a collaborative and agentically engaging process as one way of strengthening their advisor identities. Therefore, the dialogical engagement between the PAs and their educators shows us that the most prominent characteristics of their advisor identity which are appreciated by their mentors in appreciation cards turn into a personal motivational aspect for their future applications of advising.

The process of fulfilling an achievement in learning was triggered by the teachers, who created and delivered appreciation cards during the graduation ceremony of the training program. The PAs then decided to reflect on their cards together by meeting online during the summer and exchanging feedback on the organisation and language of each other’s reflections. While exchanging feedback and enjoying the peer support, they decided to write this reflective paper together. In the end, collaborating to write this article is proof of the PAs’ gains in agency through agentic engagement.

This means of reciprocal teacher and peer support through agentic engagement leads to meeting the PAs’ basic psychological needs as learners. When they took the initiative to participate in a potentially engaging activity (i.e., writing a reflection about the cards during the summer vacation, which was not a part of their training but a choice that they made), their decision fostered their autonomy. When they took the initiative to open up and express their feelings with their peers within collaborative online meetings, they fulfilled their own need for relatedness. Finally, when they sought out and attempted to master a challenging task (i.e., turning their reflections into an article to be published by reading some sample papers and taking on the literature review and proofreading stages), this fostered their competence.

It is a privilege to introduce the end-of-training appreciation cards and the reflections of the trained PAs, each of whose journeys has been a joy to witness and accompany.

PA Selin: “Determined”

I felt so thankful to receive such a great card (seen in Figure 2) from my mentor on our graduation day, and I was so happy to see that my determination was helping others as well. Later, I increased my consciousness about the reality that my determination was helping me achieve whatever I wanted in my life. It led me to have self-confidence, and I was able to have sessions with my advisees in a secure way. After each session, my confidence increased more and more, and I realized that [over-confidence] is neither good for me nor for my advisees, so I decided to be determined enough to have helpful sessions with my advisees as much as I can rather than being determined to have perfect ones all the time. I was a perfectionist and can now see that my determination resulted from being a perfectionist, and I was expecting each session to be perfect. I have realized that being obsessive about anything is not good, “perfect” doesn’t exist, and it doesn’t have to exist in order to be satisfied with my sessions. I want to use my determination to continue to have helpful sessions with my advisees in which they do not feel overwhelmed.

Figure 2. PA Selin’s Card

PA Rukiye Buse: “Persistent”

Persistent means, by definition, to continue to strive and progress without giving up despite all the difficulties…I was so surprised when my mentor defined me as “persistent,” as nobody had ever referred to me like that before (see Figure 3). When I thought about it, I realized how well my mentor/advisor-educator was observing me, and thanks to this, I discovered a feature of myself that even I was not aware of. Peer Advising was a program that I was impressed with when I first heard about it, and I did not stop waiting for 2 years to attend it. When I finally started, it turned into a journey that I have loved since the first day, connected by invisible but so strong ties. Therefore, even though I was so tired and [found it] difficult, I didn’t give up and I won’t give up. In my sessions, I persistently will be there for my advisees to [help them] realize themselves, their potential, and their light in all the steps they will take in the process. Even when it seems impossible to touch an advisee’s heart, connect with them, and help to change them, I will not stop reaching out and saying, “I am here for you.”

Figure 3. PA Rukiye Buse’s Card

PA Betül: “Shining”

“Shining” is the best and most special word in my heart. It describes my struggle in this life. I may also define myself as shining like the moon because the moon shines in the dark. I think that shining in complete darkness is so hard. The word “shining” on this card (see Figure 4) describes my shining like the moon. When most advisees speak to me, they want to come out of the darkness in which they are lost. Every session has been meaningful for me because I witness the [lives] and long “journey[s]” of my advisees. Each of them has a special and unique way of learning. However, I sometimes feel bad in some sessions because I cannot communicate effectively with the advisee. There were some sessions in which I felt insufficient, but I remind myself that it is not about me and that I am not perfect. Nevertheless, listening to all of them and accompanying them on their unique path enable me to shine. I can shine with their lights, and we can [brighten] our environment together. This journey of Peer Advisor Education was amazing for me, and I believe the same thing is valid for my other advisor friends. I promise myself that I will never quit shining with my advisees.

Figure 4. PA Betül’s Card

PA Ömer Faruk: “Explorer”

When I grabbed the card and read the term “Explorer” (see Figure 5), I started to question why my mentor chose this word to describe me. I could understand the reason when I started to question because I’m not one who wants to find an answer. I’m one who loves to question and think on and on. And this feature makes me “me.” For me, there’s not just an answer. Because the journey is not that simple to describe with a single reason-result connection. Neither am I. Both my advising journey and I grow like a tree by exploring. There are so many reasons like roots, and there are so many results which relate to those reasons like branches. There are so many different truths among those results. And don’t forget about the uncountable reasons, too. So complicated, isn’t it? Now do you think we can help advisees by just giving advice, or should we ask questions?

Will my ideas stay the same forever? I don’t think so. As I said, there is no such thing called one truth. Maybe the answer will be the same, but the reason, who knows? What am I doing now? Still thinking and questioning. What do we learn by just thinking? I don’t know. Maybe we can’t learn anything, but should we? Is there anything which we should learn? If there is, is this process permanent? Does ideal education mean just giving answers? I don’t think so. Because I think we learn not through the answers, but we just explore with questions. Then we realize different things, and we choose among them according to our viewpoint. Sometimes we can feel alone because of the differences we have, but everything has its own price, right? And as advisors we’re helping someone to question; that’s what we do right?

Figure 5. PA Ömer Faruk’s Card

PA Ayşenur: “Caring”

Being caring is simply showing concern and kindness towards others. If people can feel the attention and kindness I’ve shown to them, being caring means something more special to me. When I first saw the card (see Figure 6) at the graduation ceremony, I felt that the word really belonged to me. It was a sweet surprise that this word was chosen for me. I do care about being a person who cares not only about this education but also about daily life, and it made me very happy that people notice this. I sincerely believe that caring is a good start for mutual trust. It makes people feel more comfortable talking to someone who listens and cares about them. I disapprove of underestimating people’s problems, and it motivates me to take a step together with my advisee to solve them. Sometimes, to feel good about yourself, it is enough to know that you are valuable, and to be cared for by the people around you. And I will continue to be someone who values, listens carefully, and tries to help as much as I can. This precious card will always encourage me on my journey to become a good advisor.

Figure 6. PA Ayşenur’s Card

PA Emir Şamil: “Serenity”

There are some people in our lives who can’t show what’s inside in a short time. They can’t shine. They don’t say, “I’m here.” They just quietly wait to be understood in their own corner. They calmly watch people from their corners without any rush to understand the world, like an oyster in the depths of the ocean. I was one of these oysters until my mentor went deep into my ocean and opened my shell and named the pearl inside me “serenity” (see Figure 7). That day, I felt that I could express myself and be understood. What my mentor discovered inside my shell was that I could reach out to other people the same way and explore what’s inside them. We all have a way to the depths of the oceans in our lives, and pearls [which] are to be named. I set out on my advising journey with the gains I learned from our sharing this year to find pearls that would illuminate the darkness in the depths.

Figure 7. PA Emir Şamil’s Card

Indications of agentic engagement

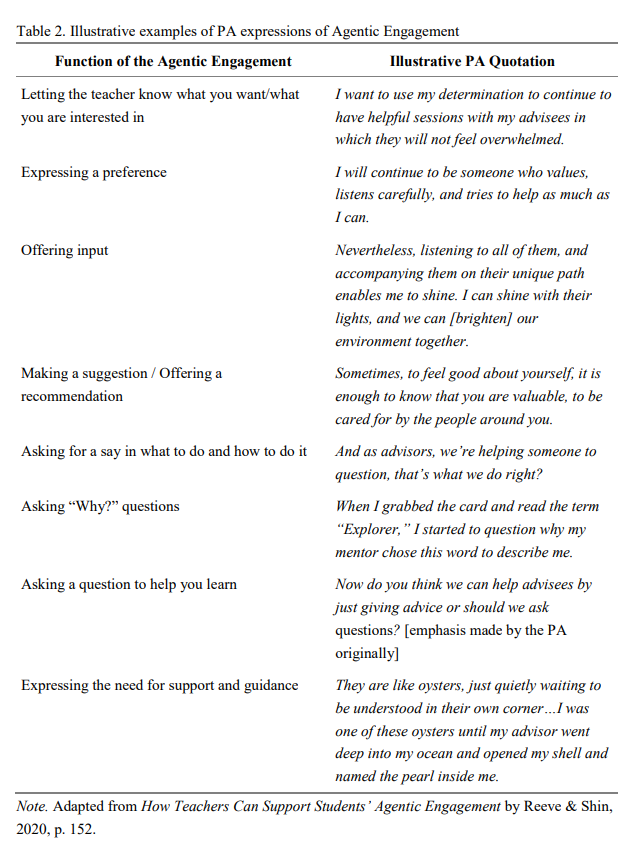

Eight illustrative examples of expressions from the PAs’ reflections which display agentic engagement are included in Table 2. They were chosen considering the example learner expressions in Reeve and Shin (2020), who focused on teacher support for learner engagement.

Agentic engagement varies in functioning. Among the various functions of agentic engagement that are seen in Table 2, the first two functions (letting the teacher know what you want/what you are interested in and expressing a preference) seem similar, with some minor differences. When learners “let the teacher know what they want” or “what they are interested in,” they refer to any ambition that they are determined to fulfill or their tendencies and wishes as learners. “Expressing preferences” refers to their choices regarding how to reach their learning goals. As for the function of offering input, it relates to improved learner functioning as the PAs make some evaluations about their own actions and draw some conclusions. Making a suggestion or offering a recommendation would be impossible if the learner functioning weren’t improved, as PAs refer to the development in their learning journey. By asking “Why?” questions, PAs can have realizations and improve their learning circumstances. In this regard, requesting help leads to improvement in the sense of relatedness.

There seems to be a common pattern in the reflections. In almost all the reflections, the PAs mention a realization of their characteristics as advisors, and this follows a functional expression of agentic engagement, which generally refers to their willingness or choice for future actions. One example of those realizations can be seen in the first reflection in which Selin’s determination seems to be not only the source of her perfectionism (in her own words) but also a way to cope with it. She expresses her determination to help other learners feel understood. Another pattern of realization accompanied by an expression of preference can be seen in the second reflection, by Rukiye Buse, as persistence turns into a promise to listen to and be there for the advisees no matter how challenging it could be. A similar pattern is seen in the third reflection. In this one, Betül offers input as she shines within a mutual enlightenment with advisees, who each have their unique features. In the fourth reflection, Ömer Faruk seems to be the embodiment of an explorer who reflects on his never-ending questions. This sets a nice example for asking “Why?” questions to come to a realization, which functions as agentic engagement with oneself. When it comes to the fifth reflection, by Ayşenur, the justification of being caring as an ideal advisor trait is accompanied by an expression of intention. Finally, in Emir Şamil’s reflection, with the metaphor of a pearl to be discovered, he promises to discover other pearls in the darkness as an advisor. This sets a nice example of how expressing the need for support is essential in developing agency in learning.

The Notion of Identity

A word cloud is an essential visual aid to highlight keywords referring to the focus of any text. It helps a text to be better understood and seen from a different angle. The word cloud below was created at a website called wordclouds.co.uk which allows the creation of word clouds in various shapes. Each reflection by the PAs was copied and pasted on the website as a whole text. The text was turned into a word cloud, with the cluster of words depicted in different sizes. The size of the words is significant, as the most commonly used words in the text are displayed at larger sizes than the others. The butterfly shape was chosen to highlight the transformational and transformative aspect of this reflective practice. Although the reflections contain the words attributed to the PAs, the most repeated word appears to be “advisees,” which is written in the biggest font in the centre. This demonstrates their transformation from their “advisee” to their “advisor” selves. In other words, the prominence of the word “advisee” shows that they are transforming into advisors, because their advisees become such important figures to them. Advisees, as the PAs’ social engagement partners within the advising context, appear to be the most crucial factor in the process of becoming autonomous advisors.

Figure 8. A Word Cloud of the PAs’ Reflections. Made by the author at the website wordclouds.co.uk.

Conclusion

The need for learners to receive more personal support is a major catalyst for the Peer Advisor Education training. During this pilot training, the participants became more effective learners within autonomy-supportive learning while they were involved in agentic engagement, and this process promoted their social relatedness. This reflective paper utilizing self-determination theory explored the dynamics of autonomy support within reciprocal agentic engagement and its impact on advisor identity. As a result, we recommend that advisor educators focus on appreciating, vitalizing, and supporting learners’ motivational satisfaction during the delivery of the course. In addition, seeing “advisees” in the heart of the butterfly-shaped word cloud evokes one principle of advising (Kato & Mynard, 2016): It’s about the advisee, not the advisor. In this sense, the illustration might be interpreted as proof of how well PAs were able to internalize this crucial principle of advising.

Notes on the contributors

Gamze Guven-Yalcin is the co-coordinator of the Learning Advisory Program (LAP), an advisor educator and an EFL instructor at AYBU-SFL. She holds Learning Advisor and Advisor Educator Certificates from Kanda University of International Studies. Her current MA study is on SDT and well-being in Advising in Language Learning. Her interests include advisor education, developing advising tools, gamification in language learning, and integrating Sustainable Development Goals into EFL settings.

Rukiye Buse Kayaalp is a certified peer advisor and a third-year student in the Psychology Department at AYBU. She graduated from AYBU-SFL in 2020. Her interests include peer advising, reading about psychological cases, and psychological improvement.

Selin Doğan is a certified peer advisor at Ankara Yildirim Beyazit University. She is a second-year student in the International Relations Department. She graduated from AYBU-SFL in 2021. She enjoys engaging with different cultures and varied perspectives.

Betül Öztürk is a certified peer advisor at Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University. She belongs to the Psychology Department. She graduated from AYBU-SFL in 2022. Her hobbies are learning new languages and different cultures, reading philosophy books, and theatre.

Ayşenur Neşeli is a certified peer advisor at Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University. She is a first-year student in the Department of Medicine. She graduated from AYBU-SFL in 2021. She enjoys reading books, exploring new places, and learning about different cultures.

Emir Şamil Doğan is a certified peer advisor at Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University. He is a first-year student in the Architecture Department. He graduated from AYBU-SFL in 2021. His hobbies are drawing, reading, and writing.

Ömer Faruk Acar is a certified peer advisor. He is a second-year student in the Department of Economics. He graduated from AYBU-SFL in 2021. Some of his hobbies are writing, music, and movies. He is also an overthinker. His future goal is to become an academician.

References

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(2), 164–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011.x

Benson, P. (2007). Autonomy in language teaching and learning (State-of-the-art article). Language Teaching, 40(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0261444806003958

Cranton, P. (2006). Transformative learning. In P. Mayo (Ed.), Learning with adults: A reader (pp. 267–274). Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6209-335-5_20

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behaviour. Plenum. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the life cycle: Selected papers by Erik H. Erikson. W. W. Norton & Co. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207284.1961.11508152

Hawkins, M. R. (2005). Becoming a student: Identity work and academic literacies in early schooling. TESOL Quarterly, 39(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588452

Huang, J. P., & Benson, P. (2013). Autonomy, agency and identity in foreign and second language education. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 36(1), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1515/cjal-2013-0002

Karaaslan, H., Howard, S. L., Güven-Yalçın, G., Şen, M., Akgedik, M., Sınar-Okutucu, E., Arslan, G., Güllü, A., Güler, A. T., Şen, H., Atcan-Altan, N., Çakır, A., Akıncı-Akkurt, P., Omerovic, E., Rocchi-Whitehead, F., Esen, M., Üstündağ-Algın, P., Kotik, G., Üstün, A., & Kılıç, N. (2019). The visual message board: A closer look at the learning advisors’ identity construction process. Relay Journal, 2(2), 333–358. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020209

Kato, S. (2012). Professional development for learning advisors: Facilitating the intentional reflective dialogue. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(1), 74–92. https://doi.org/10.37237/030106

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

Matos, L., Reeve, J., Herrera, D. & Claux, M. (2018) Students’ agentic engagement predicts longitudinal increases in perceived autonomy-supportive teaching: The squeaky wheel gets the grease, The Journal of Experimental Education, 86(4), 579–596, https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2018.1448746

Mezirow, J. (2009). Transformative learning theory. In J. Mezirow & E. W. Taylor (Eds.), Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community, workplace, and higher education (pp. 18–31). Jossey-Bass.

Reeve, J. (2012). A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 149–172). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_7

Reeve, J., Cheon, S. H., & Yu, T. H. (2020). An autonomy-supportive intervention to develop students’ resilience by boosting agentic engagement. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(4), 325–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025420911103

Reeve, J., & Shin, S. (2020). How teachers can support students’ agentic engagement. Theory Into Practice, 59(2), 150–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2019.1702451

Reeve, J., & Tseng, C. M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(4), 257–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.05.002

Taylor, C. (1989). Sources of the self: The making of the modern identity. Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjf9vz4

Wakefield, C. R. (2016). Agentic engagement, teacher support, and classmate relatedness—A reciprocal path to student achievement (Publication No. 2757) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Nevada, Las Vegas]. UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. https://doi.org/10.34917/9112205

Dear Gamze and the amazing PA team,

Thank you very much for your insightful reflections and inspiring ideas for developing a peer advisor training program. As I started a student assistant (SA) program at my institution last year, this paper truly excited me with a number of practical ideas that I would like to incorporate into our training. Particularly, giving PA appreciation cards with representative keywords sounds like a wonderful idea!

I’ve added it onto my to-do list for the next academic year.

In the Japanese context, student staff (regardless of their given titles) are still recognized as subordinates of teachers, albeit their powerful and postive impact on the school community. Developing a well-structured and research-informed PA program is certainly important to show the prominence of student agency as part of pedagogical practice as well.

I also found the adoption of perspectives on student identity and agency in the advisor training intriguing. In my own experience working with our SAs, their agentic actions also led to their growing confidence and exploration of new identities. As discussed in SDTs, the reciprocity of learners’ psychological needs and their learning environment can really bring positive change in the community of learners, and from your report, your program successfully fostered the positive loop of learning!

There are some questions that came up in my mind:

For PAs:

-From your reflections, I can tell your advising was a great support for your advisees, and I was wondering if you had a chance to ask about their experience with peer advising? If so, what kinds of comments (or keywords) appeared most?

-As a PA, how would you like to further develop the advising training program? How would you like to get involved with the program as an experienced PA in the future?

For Gamze: How would you define the role of advisor trainer in the program? You have substantial experience in advising as well as training advisors, I believe—do you have any suggestions for those who would like to start a training program?

Apologies for the multiple questions! This report certainly has sparked my motivation to establish a better SA program in my institution too—I can’t wait to hear how the PA program will continue to shape as learner agency grows within your community.

Once again, congratulations on the development of such an engaging program for your students. I hope to learn more from your practice and share our story in the near future too.

As a Peer Advisor, I would definitely like to further develop myself by contacting with my Peers both online and face to face by sessions and I would like to take Teaching Assistant course and become a TA. I think that there are no limits to show what we can do both on online and face to face platform by being Peer Advisors because every peer of mine needs someone to talk to and be understood by somebody. I will be there for them to relieve when they want to do so.

Dear Kie,

Allow me to congratulate you on your initiating a student assistant (SA) program. As a qualified and experienced advisor educator, you will surely establish a better SA program in your institution, which will turn into a playground for learners where they can show the prominence of their agency and enjoy their mutual growth. I know how supportive you are from my personal experience of your truly empowering feedback on my journey of becoming an advisor 5 years ago. Now, I second this exhilarating feeling of receiving much more appreciative words of yours on our advisor training program and our PAs.

In (peer) advisor training, it is crucial to shift from a passive system solely based on the trainer’s performance to an active learning process where the trainee takes an active role and the trainer serves as a mentor guiding and contributing to the advisor’s own development. This involves not only helping peer advisors develop a “learning to learn” approach but also helping trainers develop a “learning to guide” mindset that focuses on creating inspiring and effective learning environments. Rather than relying solely on knowledge transfer, (peer) advisor training should aim to create spaces of experience that prioritize advisor development and growth, which inevitably promote their agency and identity.

In this sense, the role of an advisor trainer in a program is to equip advisors with the necessary knowledge, skills, and tools to effectively support and guide other learners towards achieving their goals. An advisor trainer should provide advisors with a comprehensive understanding of the field, including the theoretical underpinnings, practical applications, and ethical considerations.

In addition, an advisor trainer should help advisors develop effective communication and interpersonal skills, as well as the ability to identify and respond to the unique needs and circumstances of their advisees. This may involve training on active listening, empathy, and problem-solving techniques, as well as providing opportunities for advisors to practice and receive feedback on their skills. This ends up in developing an ongoing, even a life-long relationship with one another.

When starting a training program for advisors, one can consider some suggestions below:

1. Identify the target audience: Consider the background and experience level of the advisors you will be training, as well as the specific needs and goals of the program participants. There need some adaptations of the advisor education program considering the contextual features and cultural background of the target audience. In our case, we had to add some sessions focusing on the difference between giving direct advice and exploration of the issue together with the advisee. This highlighted the indirect role of advising rather than becoming an authority of an advice giver.

2. Develop a curriculum: Create a structured and comprehensive curriculum that covers the necessary content areas, including theoretical knowledge, practical skills, and ethical considerations. In our context, we designed a flexible pilot program for learners that they could benefit from voluntarily. In the following academic year, we were able to get acceptance from the Senate to start up a brand new elective course through which learners could get credits for their departments.

3. Utilize a variety of teaching methods: Incorporate a variety of teaching methods, such as lectures, discussions, case studies, and demo-sessions, relay races and group/one-to-one sessions with real students to engage learners and accommodate different learning styles.

4. Provide opportunities for practice and feedback: Provide chances for advisors to improve their abilities and receive constructive criticism from both peers and instructors in order to optimize their learning process. In our situation, recognizing the importance of interaction between advisors and their advisees, we introduced a digital advising program that involved peer advisors during their training. They collaborated on creating a website where they shared their personal reflections and engaged with other learners through a chat service. This initiative allowed us to not only encourage PA independence but also to establish a new service to aid other students in the institution.

5. Emphasize ongoing professional development: Highlight the importance of continuous professional growth by motivating advisors to pursue learning opportunities such as workshops, conferences, and networking events beyond their initial training. In our specific scenario, we not only presented at an international conference together last year but also allowed volunteer PAs to enhance their mentoring skills and gain experience by serving as TAs in our Advising in Language Learning 101-102 elective course.

6. Evaluate the effectiveness of the program: Regularly assess the effectiveness of the program, including participant satisfaction and learning outcomes, to ensure that it is meeting the needs of the advisors and achieving its goals.

Overall, starting a training program for advisors requires careful planning, preparation, and ongoing evaluation to ensure that it is effective and meets the needs of the participants. Below are some studies that one can get some ideas about advisor training programs:

1. Chen, C., & Gottlieb, M. C. (2016). Advisor training and development: Best practices in leadership education. Journal of Leadership Education, 15(4), 95-104. https://doi.org/10.12806/V15/I4/R6

This study explores best practices in advisor training and development, drawing on the experiences of leadership education programs. It highlights the importance of developing advisors’ leadership skills, providing ongoing support and feedback, and creating opportunities for experiential learning.

2. Boyd, E. M., & Fales, A. W. (1983). Reflective learning: Key to learning from experience. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 23(2), 99-117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167883232011

This study examines the concept of reflective learning and its importance in advisor training and development. It argues that advisors need to engage in critical reflection on their experiences in order to deepen their understanding and enhance their effectiveness.

3. Tull, A., & Foubert, J. (2018). Advising and mentoring for leadership development: A review of the literature. Journal of Leadership Education, 17(2), 118-130. https://doi.org/10.12806/V17/I2/R4

The study explores the relationship between advising and mentoring in promoting leadership development. The authors conducted a comprehensive review of the literature and identified key themes related to the role of advising and mentoring in leadership development, the characteristics of effective advisors and mentors, and the impact of advising and mentoring on leadership outcomes. The authors argue that advising and mentoring can be effective strategies for developing leadership skills and that effective advisors and mentors possess certain qualities, such as empathy, authenticity, and knowledge of leadership theory and practice.

Thank you so much for the multiple thought-provoking questions that sparked that reply. Apologies for the length of the reply, though!

Looking forward to hearing about the positive changes in the community through your SA Program.

Warmest regards,

Gamze

Dear Kie,

I’m Rukiye Buse Kayaalp. I am a 3rd-year student at Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University, Department of Psychology. I am a Peer Advisor who heard about Peer Advising Training 4 years ago and has been following it for 4 years persistently.

Every time I read our cards and what we wrote, I am proud of my advisor friends. I feel grateful to Ms. Gamze for everything, and also I feel grateful to you for your interest and amazing feedback. This journey has been affecting my life for more than 3 years in a positive way. I want to continue to influence and be influenced, to shine and to be a light to the dark parts of advisers.

The effect of what I said in the sessions I had on advisees made me fly like a butterfly. This effect seemed so incredible and unpredictable that at first, I had a hard time believing it. Advisees didn’t need big words or directions, they just wanted to be able to explain and know that they were understood. While I was asking whether ‘it was useful’ or ‘could I do it,’ the thanks they gave me in the reflections they wrote after the sessions were the most valuable gifts for me. In the feedback they gave, I saw that their awareness increased and they were able to look at them from a perspective they had never looked at. In their verbal and written feedback, I witness sentences such as “I never thought of it from this perspective”, “She was very understanding”, and “Today I will start the x job (which I postponed for a long time)”.

My road has never changed as a peer advisor. Of course, It couldn’t be separated from an area that is so connected to my department and shares the same sensitivity. I am ready to do my best to develop and to ensure that something reaches more people in this field and to do more beneficial to more people.

Thank you very much for your feedback.

Kind regards,

-Rukiye Buse KAYAALP

My apologies for the miscitations in the 2 suggested studies. The DOI links are correct, though. Here are the corrected ones:

1. Bright, D. S., Caza, A., Turesky, E. F., Putzel, R., Nelson, E., & Luechtefeld, R. (2016). Constructivist Meta-practices: When Students Design Activities, Lead Others and Assess Peers. Journal of Leadership Education, 15(4). http://dx.doi.org/10.12806/V15/I4/R6

The study by Bright et al. (2016) focused on constructivist meta-practices, specifically when students design activities, lead others, and assess peers in the context of leadership education. The authors argued that incorporating these practices into leadership education can enhance students’ critical thinking, problem-solving, and leadership skills. The study was conducted in a leadership course where students engaged in these practices and reflected on their experiences. The results showed that the students perceived the activities as valuable and effective in developing their leadership skills. The study suggested that incorporating constructivist meta-practices into leadership education can enhance students’ learning experiences and development as leaders.

3. Jenkins, J. (2018). A Framework for Virtual Leadership Development in the Intelligence Community. The Journal of Leadership Education, 17, 60-82. https://doi.org/10.12806/V17/I2/R4

The study by Jenkins (2018) proposed a framework for virtual leadership development in the Intelligence Community. The author argued that as technology continues to change the way people work, it is essential to develop leaders who can effectively lead virtual teams. The framework consists of four components: (1) Virtual Leadership Competencies, (2) Virtual Learning Environment, (3) Virtual Coaching and Mentoring, and (4) Virtual Assessments. The study suggested that this framework could enhance the development of virtual leaders in the Intelligence Community and improve their ability to lead virtual teams effectively.

Dear Kie,

Initially, I’ve been happy about your pleasant comments and questions regarding the PA program. As a Peer Advisor, I can say that the program was a long and amazing journey for us. It was a productive journey in which we discovered ourselves and learned how to help our peers as well. At the end of the PA education program, each of the PAs had a certificate and these special cards that define each of us. I think these cards with special words were unforgettable for us, so I agree with you about using the card idea in the SA program.

We received pretty feedback from our peers as a result of the interviews we made during the PA training, and the one-to-one meetings we held as peer advisors. Besides, Advisees fill out the consent form at the beginning of the session, and the feedback form at the end of the session. Therefore, our sessions and their feedback are officially recorded. Based on the feedback from the advisees, I can say that they state that peer advising is very productive for them and that talking about some issues with their peers is better for them and they feel relaxed. Also, we can use some tools for time management, life, success, learning problems, etc. I believe that using these tools also makes the advisees more active and this increases their motivation. Additionally, we hold PA-Led Sessions in order to provide students with speech and share their ideas freely on certain topics. Based on my recent PA Led Session on self-acceptance, I can say that we also help advisees accept themselves through our interviews. Self-acceptance helps you feel better about yourself and makes you feel capable of dealing with life’s challenges(Meghan Marcum,2022). At the end of our sessions, most advisees state that they are able to feel better and stronger against life. It shows that peer advising has an huge effect on their self acceptance.

We are first students who had a peer advising training for the first time last year. We wanted to reach lots of students and spread this education to increase the efficiency of our university students.For this reason, nowadays, the Peer Advising Education is in force as RALL 101 elective course,and our university students can choose it if they want to have this training.

Consequently, we continue our peer advising journey by going further than the first step we took.

We try to improve peer advising day by day as you read. I am everywhere on this journey,and I will be there at all times.

Thak you for your valuable questions.

Best regards,

Peer Advisor Betül