Jessica Zoni Upton, Nagoya University of Foreign Studies, Japan

Naoya Shibata, Nagoya University of Foreign Studies, Japan

Richard Hill, Nagoya University of Foreign Studies, Japan

Zoni Upton, J., Shibata, N., & Hill, R. (2023). Conversation Space: Trialling Self-Access Services. Relay Journal, 6(1), 5-31. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/060102

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

This report summarises findings and observations from trialling self-access services in a social space named Conversation Space (CS) at a Japanese university. This trial targeted first- and second-year students, and data was collected through observation notes. The notes were coded and categorised into three main themes: motivation, use of CS, and management and design. Findings show that students utilised CS mainly to practise speaking the target language with their friends and learning advisors, receive learning advice from learning advisors, and to socialise. Furthermore, the trial also highlighted the necessity of active promotion for CS by stakeholders and the importance of learning advising training in order to further develop the autonomous learning space. Although much was learned through this trial, the authors believe that support from the institution is pivotal in order to create a space that can fully support learners’ autonomous development.

Keywords: EFL, Japanese university, self-access learning centre, management

There is a wide variety of differently orientated physical self-access learning centres (SALCs) around the world, each having a range of differing underpinning philosophies (Hobbs & Dofs, 2017). SALCs are generally considered out-of-class learning spaces which make a vital contribution to foreign language proficiency (Benson, 2017). Considering this, should a university that predominantly promotes language learning invest in a SALC? The trial in this particular study was conducted at a university of foreign studies in Japan that currently does not have a dedicated SALC space. The authors of this paper wanted to pilot SALC services to witness the effects on the students participating and assess whether any observations or conclusions could be made as to whether the university should invest in a SALC or not. Although instructors at numerous institutions realise the potential SALCs have to facilitate learner autonomy, some administrators might seek to judge whether SALCs can work successfully in their contexts and might be reluctant to make a financial commitment before officially establishing them. Therefore, the piloting of SALCs might need to be conducted with limited financial support and resources in some institutions. In this paper, based on observation notes gathered by learning advisors, findings from an ongoing SALC project conducted in a private university in central Japan are reported. Starting with the theoretical background of SALCs in the Japanese university context, the following sections will present the background of the institution and of the people involved in this trial, its implementation throughout the academic year, the data collection and analysis, the resulting observations, and finally the authors’ suggestions for going forward with the study.

Literature Review

Among the various factors necessary for successful second or foreign language learning, learner autonomy is one of the most important elements for language learners to sustain their learning engagement. Language teachers and institutions also should facilitate their learner autonomy whilst applying many approaches, including the introduction of extensive reading and listening activities and conversation spaces (Berger et al., 2022; Kobayashi, 2020; Yang, 1998). Self-access learning centres, where learners with any target-language proficiency levels can seek to develop their independent and autonomous learning whilst utilising materials and receiving advice from language teachers and learning advisors, are also an effective means to accomplish the ultimate objective of fostering learner autonomy. Furthermore, stakeholders, especially teachers and students, can explore new teaching and learning approaches and strategies in the flexible atmosphere (Lázaro & Reinders, 2009). Thus, as Rose and Elliott (2010) suggest that more educational institutions should contemplate organising such facilities so as to facilitate language learners’ engagement, SALCs can be considered beneficial spaces for teacher and learner autonomy development as well as institutional innovation (Gardner & Miller, 2014).

Gromik (2015) mentions that SALCs might not necessarily be places for learners to improve their learning abilities, yet the importance of SALCs is recognised in many educational contexts and is evidenced by the introduction of SALCs and writing centres in many countries, including Japan. Kongchan and Darasawang (2015), for example, mention that Japan is one of the Asian countries where SALCs have been most successfully introduced. In fact, compared to 45 Japanese universities in 2019 (Chambers, 2020), the latest information released by the Japan Association for Self-Access Learning (JASAL, 2022) reports that 59 Japanese universities (e.g., Gifu Shotoku Gakuen University, Hokkaido University of Education, Kanda University of International Studies, and Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University) have introduced SALCs in their institutions. A total of 78 Japanese universities can be perceived as having SALCs and similar spaces; for instance, 19 universities (e.g., Aichi University, Kansai University, and Waseda University) host writing centres and have been registered with the Writing Centers Association of Japan (2022). Furthermore, as Reinders and Benson (2017) highlight the importance of investigating language learning and teaching beyond the classroom, an increase in journals (e.g., Studies in Self-Access Learning [SiSAL] Journal, JASAL Journal, and Relay Journal), as well as in publications on SALCs (e.g., Bowyer, 2021; Croker & Ashurova, 2012; Heigham, 2011; Mynard & Carson, 2012; Mynard & Shelton-Strong, 2022a; Telfer et al., 2022; Tweed, 2019) can be seen. They illuminate the necessity and prevalence of SALCs in many language learning institutions in Japan. Accordingly, assuming the aforementioned current situation, more universities and possibly other educational institutions may start to establish such flexible learning places where learners can engage in language learning and receive assistance from others when necessary.

SALC users have various needs, and practitioners need to offer various kinds of support for these needs. Even if learners have positive impressions of the potential of SALCs and the importance of individual language learning, they sometimes feel insufficiently competent to convey their messages and interact in the target language or have other psychological obstacles to engaging in SALC communities and autonomous learning (Asta & Mynard, 2018; Dişlen, 2011; Mynard & Shelton-Strong, 2020a, 2020b; Yarwood et al., 2019). In self-access learning, learners need to be responsible for their successful individual learning whilst exploring their own learning strategies and establishing their comfortable learning spaces through trial and error. That is, as Yu (2020) highlights, “learners need to have basic conditions to foster their autonomy in English learning, i.e., attitudes, motivations and strategies” (p. 1417). Therefore, it is vital for SALC teachers and assistants to offer sufficient language, and possibly psychological, support for (future) users to raise their confidence in their target language abilities and sense of belonging in the community (Carson & Mynard, 2012; Mynard & Shelton-Strong, 2022b).

As Gardner and Miller (2021) highlight, “[t]he key to a continued success for self-access learning lies in the people involved in it” (p. 61). These people are not necessarily only learners, teachers, and learning advisors, but also faculty members and other stakeholders who can contribute to a SALC’s development. The practitioners need to receive financial and material resource support from their own institutions in order to manage the SALCs efficiently and provide users with sufficient materials of various types (e.g., books, newspapers, DVDs, games, and other technological devices) and workshops to learn effective learning strategies and monitor their own autonomous learning. In addition to such materials, sufficient human staffing, continuous training, and research assistance are also essential to maintain efficient and effective self-access learning spaces for stakeholders (Mynard, 2019). Moreover, Priyatmojo and Rohani (2017) mention that constructive promotion from faculties and institutions is vital to establish beneficial self-access learning settings. Benson (2017) also argues that ongoing change in perspectives regarding second language learning and teaching unavoidably affects practitioners’ ideas about the roles of SALCs. That is, under the circumstance where various external and internal factors (e.g., new technology, online teaching, and the advising spaces) might influence the importance of autonomous learning, SALC teachers, advisors, and managers need to foresee the future changes in SALCs (Hobbs & Dofs, 2017).

Moreover, financial and material resource assistance from institutions and faculties is crucial to innovate and develop SALCs. Although the positive results of SALCs have been reported in many settings, depending on institutional cultures, managers and practitioners might encounter challenges in negotiating with administrators regarding financial and material support (Shibata, 2022). In the current economic climate, many institutions might not willingly approve new projects, risk spending much money, or offer resources for them unless the needs of and the expected benefits for stakeholders (e.g., learners, parents, teachers, and faculties) are ensured in the community. Thus, practitioners who plan to have SALCs or similar learning spaces may need to explore ways to conduct trial projects with limited or no investment from their institutions until SALC management becomes successful in those contexts.

Background

In the following section, the authors will explore the context where the trial was held, as well as explain their own background in reference to their role as learning advisors.

Institutional background

The university where the SALC trial was conducted was established in 1988 as a school of foreign studies. As of 2022, the university offers 11 foreign language courses and exchange programs for all majors. Nonetheless, the university does not currently have a SALC. There is academic support available in different locations for different departments, and opportunities for conversations with international students are available in yet another location on campus. Books, such as graded readers, and foreign movies are only available at the library and media centre. While these facilities contain factors of a SALC, there is no single space where all common SALC features are offered. As a result, it might be inconvenient for students to go to different locations each time depending on their needs. In contrast, Mynard and Stevenson (2017) explain that the SALC at Kanda University of International Studies is a space that provides materials, speaking practice, workshops, events, group study rooms, access to learning advisors, and the chance to socialise in the target language in a relaxed environment. All of these opportunities are contained in one large physical space that is clearly signposted and designated so that students are fully aware of how things work and how they can use them.

Other universities’ SALCs, such as that of Meijo University in Nagoya, Japan, have the facilities to hold presentations for all students, and tours designed to increase understanding of how a SALC works are provided at the start of each academic year at such facilities. On the other hand, at this university, there are no tours that cover all facilities on campus, nor one single location designated for students to receive language advising, engage in conversation practice, or socialise whilst developing a second language or reading and studying quietly. In making this comparison, we recognise what aspects already available at other SALCs are missing at the university in this trial, despite the common goal we share with them in wanting to help students develop learner autonomy: a capacity to take control of one’s own learning and make informed choices with a level of awareness and control of learning processes achieved through reflection.

Learning advisors’ backgrounds

The three authors conducted this trial as learning advisors, and all three share an interest in learner autonomy. The first author had no previous experience as a learning advisor (LA). However, they had previously researched different aspects of learner autonomy (Hirano & Zoni Upton, 2022; Zoni Upton & Hirano, 2022). Furthermore, they had worked at this university for the longest of the three authors and had overseen various conversation programs in and outside of a typical classroom setting. The other two authors, on the other hand, had received advising training and worked as learning advisors in another institution. The second author had mainly offered consultations to undergraduate and postgraduate students on academic writing, conversation advice, and English proficiency test preparation. Similar to the first author, the second author had also published and presented on learner autonomy and teacher development (Shibata, 2019, 2020a). The third author had offered consultations on time management, conversation advice, and English proficiency test preparation. The third author had presented on the affordances of SALCs and on being a “good” conversation partner at a conference on self-access learning (Hill & Primeau, 2017). As a result, we could offer experience to the project and all saw value in conducting a SALC trial in an institution without a SALC.

Implementation

In the following section, we will introduce how the trial was conducted over the course of the 2022 academic year, as well as the differences in implementation between the spring and fall semesters.

Spring semester SALC services trial

At the start of the academic year in April 2022, the authors agreed that it was important to first gauge student interest before deciding whether to proceed with the trial. A survey (see Appendix A) was designed using Google Forms and distributed to the authors’ students (English and English Education majors) through Google Classroom in April 2022. The survey inquired about students’ opportunities to use their target language in conversation outside of their language courses at university and about their interest in joining a possible conversation practice on campus or online. The anonymous survey was completed by a total of 106 first- and second-year students. The survey results indicated that 66.0% of students who completed the survey spent less than 1 hour every week speaking in their target language. Additionally, 58.5% stated that they had difficulties finding a conversation partner. Finally, when asked whether they would be interested in participating in conversation practice, 66.0% expressed interest in joining if it were held on campus and 42.5% if it were online. Survey results confirmed what the authors believed, that many students might not have enough opportunities to practise using the target language outside of class and that a dedicated space inside the university would be welcomed.

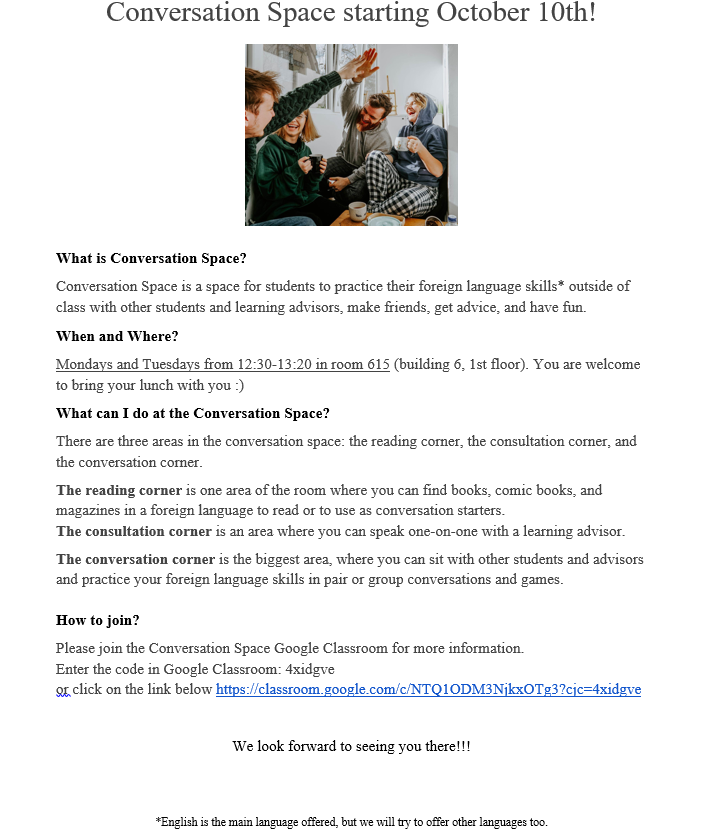

An initial trial of the SALC services began in the spring semester of the 2022 academic year, from May to July, for a total duration of 3 months. The services were promoted under the name “Conversation Space” (CS) to first- and second-year students of the three authors as a space for them to practise speaking in their target language outside of class with other students and teachers, and it was held for 50 minutes during lunchtime on Mondays and fifth period (4:30 p.m. to 6:00 p.m.) on Fridays. The choice of promoting CS only to this specific group of students was influenced by two reasons: The authors did not have to involve other teachers or administrative staff, but just promote it to their own students; additionally, only first- and second-year students were physically present on campus while third- and fourth-year students were taking classes online or at another campus. The choice of the name “Conversation Space” stemmed mainly from two reasons: It would be easier for students to understand the goal of the space just from the name, and it felt inaccurate to call it a SALC when it in fact lacked many of the exemplary aspects, most evidently its own space. CS was indeed located in one of the authors’ classrooms, a choice made based on its size (capacity: 48) and students’ familiarity with the room. Furthermore, the room only had old heavy desks and chairs, which were set up in three neat rows of two facing the teacher’s desk and were hard to move. The choice of days and times for CS were prompted by an attempt to reach both first- and second-year students who attended the authors’ classes on Mondays and Fridays respectively. Moreover, considering the increased use of technology in the classroom forced by the Covid-19 pandemic, the Friday session was offered in an online format, using Zoom. Another implementation of technology to facilitate the management of the trial CS was through the use of Google Classroom and Google Docs. The authors created two Google documents, one for signing up in advance and one to sign when joining a session. The first file (see Appendix B) was uploaded to each author’s Google Classroom, so all students could access it freely and the authors would be notified of how many students were planning on attending that week. The second file (see Appendix C) was printed each week and brought to CS for participants to sign so that authors had a record of attendees.

Fall semester SALC services trial

Based on the observations of the first semester trial, CS was updated in the second semester to include more elements of a SALC and extend its reach to additional students. The fall semester iteration of CS was conducted from October to the end of December and was promoted to all first- and second-year students in six departments (British and American Studies, English Education, French Studies, Japanese Studies, Chinese Studies, and World Liberal Arts). In order to broaden the target group, fellow full-time EFL teachers in the department were asked to spread the word and share the information on their Google Classrooms. Following the example of more established SALCs in Japan (e.g., Nagoya City University, Kanda University of International Studies), a site was created especially for CS on Google Classroom for all information to be readily available in one place for students and teachers. On the page, people could learn what CS was, when and where to join it, what services were available, who the LAs were, and what type of advice they could offer; the page also contained a sign-up sheet for consultations with one of the LAs. Moreover, with the addition in the second semester of a reading corner in the physical space of CS, every week the authors uploaded a book recommendation from the selection provided. The creation of a specific information page for CS sessions was not the only innovation in the fall semester. In fact, the fall semester trial implemented the following changes:

-

-

- Students were no longer asked to sign up in advance of joining CS sessions;

- the days and times were changed to lunchtime on Mondays and Tuesdays;

- the online option was removed;

- a reading corner was created;

- card games and board games were made available to use during the sessions;

- consultations with LAs were introduced.

-

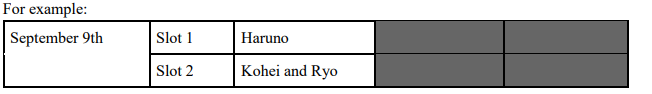

Whilst the pre-sign-up sheet was removed, the on-site sign-in sheet was kept to collect data on actual participant numbers. The Friday online sessions were replaced with Tuesday lunchtime sessions partly because of the unpopularity of the online format in the previous semester and also because, similarly to Friday, second-year students would be on campus and able to participate on Tuesdays. Finally, based on two of the authors’ previous experiences as LAs at a SALC, the room hosting CS sessions was reorganised into three spaces: a conversation corner, a reading corner, and a consultation corner. As a result of the financial and spatial limitations of CS, books for the reading corner were bought on authors’ individual research budgets and stored in a cabinet preinstalled in the classroom so that books could be easily stored away when the space was being used for teaching. One-on-one consultations, commonly found in SALCs (Hobbs & Dofs, 2017), were made available for each session. Students could consult with any of the three LAs depending on the day. Whilst all three LAs were present in CS for each session, consultations were provided by a different LA each day based on a rotation system, as shown in Appendix D.

Data Collection and Analysis

In the following section, the authors will describe which data was collected during the trial and why, followed by an explanation of how the data analysis was conducted and analysed.

Data collection instruments

This trial analysis draws upon two main data sources: observation notes and sign-in sheets. Although obtaining additional data from diverse sources, such as students’ reflections and interviews, would have been preferable, it would have entailed asking a regular group of participants for weekly data, which the authors deemed beyond the scope of the trial of SALC services. Indeed, the authors believed that such data collection could have affected the relaxing and casual atmosphere of CS and that the reflections might be perceived not as autonomous learning tasks, but as homework. After each session, the LAs would write down their observations in a shared Google document so that each could add what another had overlooked or not noticed. A total of 15 log entries were recorded between the start of October and the end of November. Likewise, sign-in sheets were collected at the end of each CS session in order to verify participant numbers. In addition, the authors sent participants a survey at the end of the fall semester to collect students’ perspectives on the usefulness and effectiveness of CS. However, as the authors did not have the survey data collected at the time of this writing, participants’ survey data is not included in the data collection for this trial.

Data analysis procedures

Qualitative data from observation notes were initially analysed using inductive coding (Given, 2008) to find common patterns. In qualitative research, it is vital to report the estimation of coding reliability and the reliability of coding scheme utilised by multiple coders in order to avoid unintentional biases and raise the validity of the findings for stakeholders, including readers, practitioners, and faculty members (Mackey & Gass, 2022). All the observation notes were coded thematically by the first and second authors using MAXQDA 2022 analysis software. Furthermore, with the same software, Cohen’s kappa (κ), defined as “the average rate of agreement for an entire set of scores, accounting for the frequency of both agreements and disagreements by category” (Mackey & Gass, 2022, p. 183), was estimated to ensure the intercoder reliability. As a result, a Cohen’s kappa value of 0.91 was found. According to Plonsky and Derrick (2016), a Cohen’s kappa value of 0.87 can be perceived as sufficient intercoder reliability in applied linguistics. Thus, the intercoder reliability of qualitative data analysis can be considered high in exploring the findings in this trial.

Observations So Far

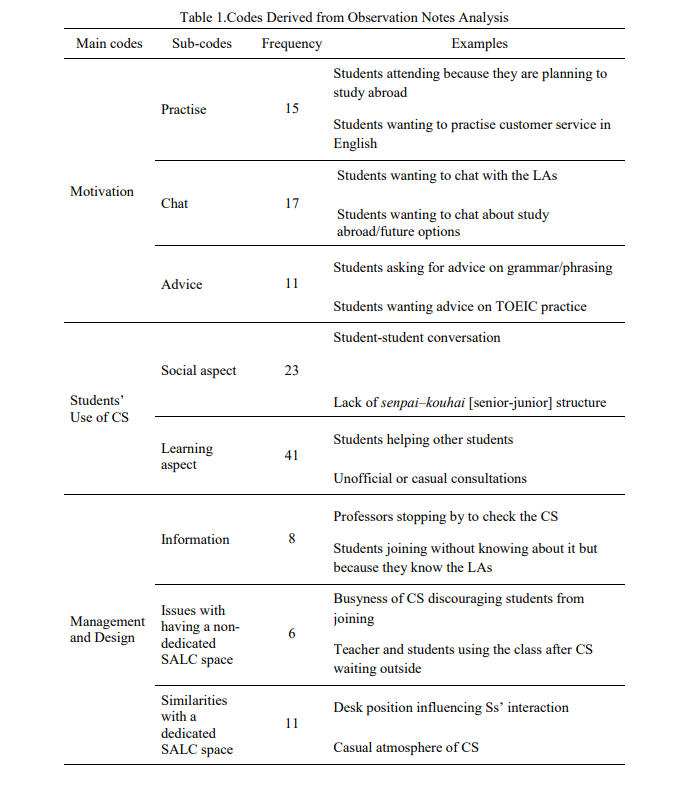

Reported below are the preliminary results of the CS trial in the fall semester. Sign-in sheets collected at the end of each session reveal that all sessions were attended by students, with participation numbers fluctuating between a minimum of two students and a maximum of 21. Whilst the numbers are relatively small when compared to the audience to which it was promoted (which could potentially have been around 500 students), the authors believe that the consistency of repeat student participation every week shows positive interest in what the authors are trying to achieve through CS. For further insights into the management and outcomes of CS, the authors thematically coded observation notes and found three main codes (See Table 1), each with their own subcodes: participant motivation, participant use of CS, and CS management and design.

Participant motivation

The first code to emerge from observation data analysis was that of participant motivation. Data show that students joined CS for three main reasons: to practise, to chat, and to get advice. The main difference between the codes “chat” and “practise” can be found in the underlying reasons for joining. Some students, especially the 10 regular participants who joined almost every week, came to chat about casual topics and use their English conversation skills. At the same time, observations show that other students joined to practise for specific reasons, such as to practise customer service in English to use at their part-time jobs or in preparation for studying abroad. Considering the topic and time restraints of English classes, which are often only 90 minutes long and follow a set curriculum and textbook, a space such as CS offers each student the opportunity to practise specifically the target language skills of their choice. Similarly, conversation topics varied from everyday life and interests to future plans and goals, at the discretion of the students. One thing which was often reported on was that some students joined CS specifically to chat with the LAs. Most of the participants were, in fact, students in the LAs’ classes. This could indicate that having teachers manage the space, rather than specially appointed LAs or exchange students (as is the case with the other English space in the university), provides a familiar environment where students can feel comfortable and build rapport with their teachers, something which is not always possible in the classroom. At the same time, this could indicate a general inclination to engage with someone whom they consider a “native speaker,” rather than with a peer. However, there is no currently no data to verify this speculation. Finally, observations indicate students sought advice on a variety of topics, including TOEIC, grammar, and school projects. Although a space for advising was provided in the Conversation Space, no students utilised it officially. Instead, they asked for informal advice from the LAs whilst having casual conversations. This might indicate that CS users in this specific context found it more accessible to talk to teachers and advisors in a situation where other people were talking around them (Kato & Mynard, 2016).

Participant use of CS

CS was originally promoted as a space “for students to practise their foreign language skills outside of class with other students and learning advisors, make friends, get advice, and have fun” (see Appendix E). After analysing observations on how students used CS, two main sub-codes emerged: the social aspect and the learning aspect. As promoted in the CS poster, observations showed that students used the CS as a social space to chat with other students, make new friends, and learn together. For instance, the authors observed that there was a complete lack of senpai–kouhai structure, a trait commonly found in Japanese culture that is defined by a change in behaviour and language when interacting with someone of a different level in the hierarchy (e.g., age or job title). In fact, first- and second-year students interacted with each other freely in English. Students were observed exchanging contact information and forming new friendships, even using CS as a regular meeting point. One interesting occurrence was the weekly sharing of homemade sweets by one of the regular participants, whose hobby was baking. This particular situation is perhaps both a result and a contributing factor to the relaxed and social aspect of CS. On the other hand, occasional casual chatting in Japanese unrelated to L2 learning was also reported, a possible result of the social nature of CS.

Nonetheless, CS was mainly used as a learning space, as students were observed using English in conversation despite struggling with vocabulary or grammar, making use of the books in the reading corner both as reading material and as conversation starters, helping each other when they could not come up with the right words, and receiving casual consultations from the LAs with their friends present. These frequent observations confirm that CS was indeed used by students in the way it had been promoted, as a social space.

CS management and design

While the majority of the observation data focus on participants’ motivation and use of CS, there were also numerous reports on the more and less successful aspects of the design and management of the trial. One recurrent positive aspect of CS was the observed comfortable and relaxing atmosphere of the space. This became increasingly evident after LAs started to move desks around to form groups. Some examples recorded in the observations include students discussing private topics, such as relationship concerns, with LAs and other students, as well as regular students bringing baked goods to share with everyone, including participants whom they had never met. Two of the authors, having previous experience with SALCs, believe that a comfortable atmosphere is an essential element of such centres. As a result, these observations would seem to suggest that CS sessions demonstrated an important similarity with more established SALCs. However, not all observations reflected positive outcomes. For instance, the authors observed at three different times in the semester that some students gave up on joining or were worried about their conversation opportunities when CS sessions were busy. On several occasions, regular students expressed concerns about being able to chat with LAs if it was too busy, even enquiring about which day would have fewer people. Moreover, there were observed instances of students checking from outside the door and leaving when there was little seating available. This might indicate an issue with the amount of LAs needed and the chosen space for the CS. The presence of only the three authors as LAs might have been inadequate when estimating how many students would join to chat with them. Furthermore, unlike a SALC, CS did not have a dedicated space, but rather a normal classroom, which might not have been big enough to host all the students who sought to join. The use of a classroom also led to an unavoidable problem: managing the space while accommodating the teacher using the classroom after it was used for CS. On account of the space being a regular classroom, all management tasks such as moving desks, cleaning up, locking books and games back in the cupboard, collecting sign-in sheets, and ending the session had to be rushed so as to not create any problems for the teacher using the classroom in the period immediately after it was used for the CS. On more than one occasion, the teacher and students were reported waiting outside in the corridor. As a result, the authors stopped relocating desks and started ending sessions earlier on days when the classroom would be used immediately after. The authors believe that these observations support the need for a dedicated SALC space in the university to avoid such limitations and inconveniences on both ends. Frequent observations of professors visiting CS might suggest that there is in fact some interest in the project, as some of the same professors praised the trial and its goal and even joined on one occasion. The authors hope CS can be recognised by the host institution as an invaluable social-learning opportunity for students to practise their target language and develop learner autonomy. Officialising CS would therefore allow for the allocation of designated resources and budget which would bring CS one step closer to becoming an established SALC.

Next Steps

There are various directions and scenarios this trial and learned experience could take if it were further implemented by EFL lecturers at the university being discussed. In this section, the authors consider several hypothetical solutions and processes for continuing the trial. During the trial of CS, students had no opportunity to reflect upon their conversations and learning. Since language learners need to take more responsibility for their self-directed learning, the implementation of portfolios can be a useful approach to raise their awareness of (language) learning and potentially foster advising sessions (Valdivia et al., 2012). As reflection can help raise awareness of individual differences as learners and teachers (motivation, learning and teaching strategies, and beliefs; e.g., Hirano & Zoni Upton, 2022; Mercer, 2013; Shibata, 2020b; Zoni Upton & Hirano, 2022), the implementation of learning and teaching logs might be effective for SALC development. Furthermore, Shibata’s (2019) qualitative case study reports the direct relationship between learner beliefs and self-learning engagement. However, Hill (2021) mentions that SALC teachers and advisors may need to provide some guidance for students who lack self-reflection habits in order for them to be able to reflect upon their learning consistently and establish their future learning plans. In order to assist learners in developing their autonomy effectively, following Mynard and Navarro’s (2010) emphasis of the importance of dialogue in autonomous learning, SALC teachers and advisors may need to elicit learners’ experiences from casual conversations and provide them with opportunities to (re)consider together their appropriate learning activities for autonomous learning and scaffold their preparation for individual learning.

Similarly, although the authors observed SALC users’ activities and speaking engagements and wrote observation notes during the trial, they rarely reflected upon their own advising and teaching practice deeply. The benefits of reflective diaries for language teachers and advisors have been reported by previous research studies (e.g., Shibata, 2020a; Ukrop et al., 2019). Their findings would also apply to advising in language learning. Furthermore, the implementation of reflective tools for other purposes, including language education leadership and management development, have been suggested insomuch as practitioners can recollect their experiences and delve into possible factors for (un)successful cases (Shibata, 2022).

Despite the authors’ backgrounds, all three were still novice advisors, and many potential learning advisors lack such training and language learning experience. As Kato and Mynard (2016) highlight, “Without training, advising in a SA[L]C might not promote reflection or encourage learner autonomy” (p. 258). In order to contribute to SALCs more efficiently and effectively, professional development would be vital. Therefore, taking some professional development courses for learning advisors, such as the Learning Advisor Education Course offered by the Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education at Kanda University of International Studies (n.d.), might be an important step to innovate the self-access learning space in this specific context.

The authors believe that the university could formalise or create a SALC, but further research may be beneficial for the university to understand the value of it. If a second trial or something more official were to take place, the understanding and support of other teachers could be strengthened. The authors worked with fellow teachers to inform the students of CS. With hindsight, perhaps further explanation of the LAs’ roles and the affordances to future stakeholders was needed. Birdsell (2015) explains that many students may not even have a conceptual frame for what a SALC is, thus making it considerably important for students to be introduced to its services via clear explanation. Birdsell also adds that students tend to ask the staff, “What exactly can I do there?” SALCs “promote a more unconventional style of learning” (Birdsell, 2015, p. 272), thereby making explanation more essential. Going forward, providing orientation tours for potential users could perhaps increase usage. Similarly, having students involved in the management of the space might help with the promotion and explanation of the service: The informal aspect of having trained student staff could make CS more approachable because of the students’ closeness to potential users, and explanations could be in Japanese if necessary (Noguchi, 2013).

Furthermore, the authors did not hold any events. Events could range from casual coffee time to Halloween or Christmas parties. Events can be useful to capture the imagination of potential new users, as well as having cultural benefits, providing learning opportunities and social affordances. However, the lack of an official budget for this trial SALC meant that the teachers involved would have had to use their own time and money to finance and organise such events. Going further, events could occur with some funding.

An allocated place or space that looks different to a classroom would be a logical next step for students to better understand what CS is and how it can be useful to them. Some SALCs have areas and concepts that require students to associate the themes with the furniture. For example, Meijo University had a green carpet which signalled to students that it was a social space, and that within it, someone seeking a conversation partner to practise with may have struck up a conversation. Although foreign at first to students, it became second nature for them to associate the spaces with their meanings, possibilities, and opportunities. A classroom may still make students feel as if the conversation partners are teachers and make their English practice less open and more contrived.

In conclusion, the authors recounted their experience with trialling SALC services at their university in hope that this paper could be of use to anyone who is interested in SALCs yet have none at their institution. In fact, despite not having allocated budget, space, or resources, the authors were able to provide services commonly available at established SALCs, such as conversation, learning advice, and reading opportunities. Throughout the trial, authors noted what motivated participants to join and how they made use of the services provided, as well as ways in which the management could be improved. Survey results that are currently being analysed will provide further information about students’ motivations and experiences that will help shape the direction CS will take in the future. Effectively, by making changes in how the services are introduced and promoted to students (e.g., orientation tours), introducing self-reflection diaries for participants and LAs, and recruiting student staff, authors will seek to improve the services that CS provides and explore what obstacles might still drive potential users away. Authors hope that the continuation of CS will gain more support from potential users and faculty, and that eventually this might encourage the university to formalise it in the same way as other more established SALCs.

Notes on the contributors

Jessica Zoni Upton is a full-time EFL lecturer at the Centre for Language Education and Development, Nagoya University of Foreign Studies. Her main interests lie in intercultural communication, social psychology, and learner autonomy.

Naoya Shibata is an EFL lecturer at the Centre for Language Education and Development, Nagoya University of Foreign Studies and is pursuing an Ed.D in TESOL at Anaheim University. He has been interested in learning advising since he worked as a part-time learning advisor at the Global Plaza, Meijo University in 2017.

Richard Hill is an EFL lecturer at the Centre for Language Education and Development, Nagoya University of Foreign Studies. He has been interested in language learning advising since he worked as a part-time learning advisor at the Global Plaza at Meijo University in 2017, going on to become a full-time learning advisor at the same institution in 2018.

References

Asta, E., & Mynard, J. (2018). Exploring basic psychological needs in a language learning center. Part 1: Conducting student interviews. Relay Journal, 1(2), 382–404. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010213

Benson, P. (2017). Language learning beyond the classroom: Access all areas. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.37237/080206

Berger, M., Eto, T., Itoi, K., Pignolet, L., Rentler, B., & Saunders, M. (2022). Cultivating autonomous learning with a language learning strategy database. In P. Ferguson & R. Derrah (Eds.), Reflections and New Perspectives (pp. 53–62). JALT. https://doi.org/10.37546/JALTPCP2021-07

Birdsell, B. (2015). Self-access learning centres and the importance of being curious. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 6(3), 271–285. http://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep15/birdsell

Bowyer, D. S. (2021). Developing intercultural connections and language competence with board games. In P. Clements, R. Derrah, & P. Ferguson (Eds.), Communities of teachers & learners (pp. 276–282). JALT. https://doi.org/10.37546/JALTPCP2020-34

Carson, L., & Mynard, J. (2012). Introduction. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 3–25). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833040

Chambers, A. J. (2020). Strategies for self-access learning centers. The Language Teacher, 44(3), 40–42. https://jalt-publications.org/articles/26184-strategies-self-access-learning-centers

Croker, R., & Ashurova, U. (2012). Scaffolding students’ initial self-access language centre experiences. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(3), 237–253. https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep12/croker_ashurova

Dişlen, G. (2011). Exploration of how students perceive autonomous learning in an EFL context. In D. Gardner (Ed.), Fostering autonomy in language learning (pp. 126–136). Zirve University. https://www.academia.edu/download/32406039/Fostering_Autonomy.pdf#page=133

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (2014). Managing self-access language learning. City University of Hong Kong Press.

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (2021). After “Establishing…”: Self-Access learning then, now and into the future. Relay Journal, 4(2), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/040202

Given, L. M. (2008). The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Sage.

Gromik, N. (2015). Self-access English learning facility: A report of student use. The JALT CALL Journal, 11(1), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.29140/jaltcall.v11n1.186

Heigham, J. (2011). Self-access evolution: One university’s journey toward learner control. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 2(2), 78–86. https://sisaljournal.org/archives/june11/heigham

Hill, R. (2021). Autonomous learning: A case study of four university ESL learners and their self-study skills alongside an English language for academic purposes course online. 2021 NUFS Teacher Development Proceedings, 26–33. https://www.nufs-pd.org/symposium-schedule

Hill, R., & Primeau, R. (2017, December 16). Utilising conversation partners in self-access centres [Presentation]. JASAL 2017 Annual Conference, Kanda University of International Studies. Chiba, Japan.

Hirano, M., & Zoni Upton, J. (2022). The self-learning log: A tool for aiding learners’ autonomy, confidence, and motivation. Bulletin of Nagoya University of Foreign Studies, 10, 281–304. https://doi.org/10.15073/00001617

Hobbs, M., & Dofs, K. (2017). Self-access centre and autonomous learning management: Where are we now and where are we going? Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 88–101. https://doi.org/10.37237/080203

The Japan Association for Self-Access Learning. (2022). LLS Registry. Retrieved November 29, 2022, from https://jasalorg.com/lls-registry/

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

Kobayashi, A. (2020). Fostering learner autonomy in an EFL classroom through an action research by adapting extensive listening activities. Language Education & Technology, 57, 91–120. https://doi.org/10.24539/let.57.0_91

Kongchan, C., & Darasawang, P. (2015). Roles of self-access centres in the success of language learning. In P. Darasawang & H. Reinders (Eds.), Innovation in language learning and teaching: The case of Thailand (pp. 76–88). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137449757_6

Lázaro, N., & Reinders, H. (2009). Language learning and teaching in the self-access centre: A practical guide for teachers. Innovation Press.

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. M. (2022). Second language research: Methodology and design (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003188414

Mercer, S. (2013). Working with language learner histories from three perspectives: Teachers, learners and researchers. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 3(2), 161–185. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2013.3.2.2

Mynard, J. (2019). Self-access learning and advising: Promoting language learner autonomy beyond the classroom. In H. Reinders., S. Ryan., & S. Nakamura (Eds.), Innovation in language teaching and learning: The case of Japan (pp. 185–209). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12567-7_10

Mynard, J., & Carson, L. (Eds., 2012). Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833040

Mynard, J., & Navarro, D. (2010). Dialogue in self-access learning. In A. M. Stoke (Ed.), JALT 2009 Conference Proceedings (pp. 95–102). JALT. https://jalt-publications.org/archive/proceedings/2009/E008.pdf

Mynard, J., & Shelton-Strong, S. J. (2020a). Evaluating a self-access learning centre: A self-determination theory perspective. In T. Pattison (Ed.), IATEFL 2019 Liverpool conference selections (pp. 41–42). IATEFL.

Mynard, J., & Shelton-Strong, S. J. (2020b). Investigating the autonomy-supportive nature of a self-access environment: A self-determination theory approach. In J. Mynard, M. Tamala, & W. Peeters (Eds.), Supporting learners and educators in developing language learner autonomy (pp. 77–117). Candlin & Mynard.

Mynard, J., & Shelton-Strong, S. J. (Eds., 2022a). Autonomy support beyond the language learning classroom: A self-determination theory perspective. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788929059

Mynard, J., & Shelton-Strong, S. J. (2022b). Self-determination theory: A proposed framework for self-access language learning. Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning, 4(1), e414522. https://doi.org/10.52598/jpll/4/1/5

Mynard, J., & Stevenson, R. (2017). Promoting learner autonomy and self-directed learning: The evolution of a SALC curriculum. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.37237/080209

Noguchi, N. (2013). The importance of student staff in self-access center. In V. L. Ssali (Ed.), Student involvement in self access centers conference reports: Of the students, by the students, for the students (pp. 11–12). JASAL. https://jasalorg.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/sisac-conference-reports.pdf

Plonsky, L., & Derrick, D. J. (2016). A meta-analysis of reliability coefficients in second language research. The Modern Language Journal, 100(2), 538–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12335

Priyatmojo, A. S., & Rohani, R. (2017). Self-access centre (SAC) in English language learning. Journal of Language and Literature 12(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.15294/lc.v12i1.11465

Reinders, H., & Benson, P. (2017). Research agenda: Language learning beyond the classroom. Language Teaching, 50(4), 561–578. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444817000192

Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education. (n.d.). Learning advisor education. https://kuis.kandagaigo.ac.jp/rilae/education/courses/

Rose, H., & Elliott, R. (2010). An investigation of student use of a self-access English-only speaking area. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(1), 32–46. https://sisaljournal.org/archives/jun10/rose_elliott

Shibata, N. (2019). The impact of students’ beliefs about English language learning on out-of-class learning. Relay Journal, 2(1), 122–136. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020117

Shibata, N. (2020a). The effects of teaching reflection diaries on in-service high school teachers in Japan. Relay Journal, 3(1), 80–99. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/030107

Shibata, N. (2020b). Exploring a language learning history: The journey of self-discovery from the perspectives of individual differences. English Language Teaching and Research Journal (ELTAR-J), 2(1), 8–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.33474/eltar-j.v1i2.6415

Shibata, N. (2022). Possible practical language educational leadership and management methods. New Directions, 40, 27–46. http://id.nii.ac.jp/1476/00006841/

Telfer, D., Stewart-McKoy, M., Burris-Melville, T., & Alao, M. (2022). “Our voices matter”: The learner profile of UTech, Jamaica students and implications for a virtual self-access learning centre. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 13(1), 77–107. https://doi.org/10.37237/130105

Tweed, A. D. (2019). What learning advisors bring to speaking practice centers. Relay Journal, 2(1), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020122

Ukrop, M., Švábenský, V., & Nehyba, J. (2019). Reflective diary for professional development of novice teachers. Proceedings of the 50th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, 1088–1094. https://doi.org/10.1145/3287324.3287448

Valdivia, S., McLoughlin, D., & Mynard, J. (2012). The portfolio: A practical tool for advising language learners in a self-access centre in Mexico. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds,). Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 205–210). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833040

The Writing Centers Association of Japan. (2022). Writing center resources. Retrieved November 28, 2022, from https://sites.google.com/site/wcajapan/writing-center-resources?authuser=0

Yang, N.-D. (1998). Exploring a new role for teachers: promoting learner autonomy. System, 26(1), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(97)00069-9

Yarwood, A., Lorentzen, A., Wallingford, A., & Wongsarnpigoon, I. (2019). Exploring basic psychological needs in a language learning center. Part 2: The autonomy-supportive nature and limitations of a SALC. Relay Journal, 2(1), 236–250. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020128

Yu, R. (2020). On fostering learner autonomy in learning English. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 10(11), 1414–1419. http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1011.09

Zoni Upton, J., & Hirano, M. (2022). The benefits of self-reflection tools for foreign language learners. 2022 NUFS Teacher Development Proceedings, 42–77. https://www.nufs-pd.org/2022-symposium-schedule

Appendix A

Anonymous Pre-SALC Trial Survey

Appendix B

Monday Sign-Up Sheet

Time: 12:30-13:20

Place: Classroom 615

MAX 25 PEOPLE

| Last 3 digits of your student number | What language/s are you learning? | Do you want to practice a language other than English? | If YES, what other language/s do you want to practice? | |

| e.g. 357 | e.g. EnglishFrench | e.g. Yes | e.g. SpanishJapanese | |

| 1 | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| 3 | ||||

| 4 | ||||

| 5 | ||||

| 6 | ||||

| 7 | ||||

| 8 | ||||

| 9 | ||||

| 10 | ||||

| 11 | ||||

| 12 | ||||

| 13 | ||||

| 14 | ||||

| 15 | ||||

| 16 | ||||

| 17 | ||||

| 18 | ||||

| 19 | ||||

| 20 | ||||

| 21 | ||||

| 22 | ||||

| 23 | ||||

| 24 | ||||

| 25 |

Appendix C

In-Class Sign-Up Sheet

| Full student number | First Name | |

| Example | e.g. 21011537 | e.g. Yuina |

| 1 | ||

| 2 | ||

| 3 | ||

| 4 | ||

| 5 | ||

| 6 | ||

| 7 | ||

| 8 | ||

| 9 | ||

| 10 | ||

| 11 | ||

| 12 | ||

| 13 | ||

| 14 | ||

| 15 | ||

| 16 | ||

| 17 | ||

| 18 | ||

| 19 | ||

| 20 |

Appendix D

Consultation Sheet (November)

This is the November schedule for consultations with learning advisors at the Conversation Space. If you need to talk to any of the learning advisors, please sign up using this sheet.

Only one advisor is available for consultations each time. The colors will tell you which learning advisor is available on the day.

Each day has a maximum of two slots available. If you want to take the consultation with a friend, please sign both your names in the same slot.

Please write your name in the day and slot on which you would like to receive a consultation.

Please remember that even if there are no slots available, you may still be able to receive a consultation on the day.

Appendix E

Conversation Space Poster

Dear Jessica, Naoya and Richard,

Thank you for sharing your passion and aspirations for creating a SAC throughout this paper! As someone who has also committed to establishing a SAC in her own institution from scratch, I naturally delved into your work. Initiating a new project of this nature requires an immense amount of work in terms of planning, implementation, and evaluating outcomes. In your paper, each process was explained in detail, which I believe will be beneficial for educators and administrators who are considering a similar initiative. I found your data analysis intriguing, as it reveals the different motivational origins of students’ usage of the space. The challenges you have faced, such as using a classroom as the CS and a lack of human resources, can be serious issues based on my own experience (if you are interested, please check out my work (山本 2022; Yamamoto, 2023).

Gaining institutional support is also a significant challenge. Through my experience in developing a SAC, I’ve learned that the project needs to be known by a broader range of stakeholders in order to thrive. This means you might want to promote it not only to students but also to professors as well as school administrators. It would be a great idea to contact your school’s PR department so they can feature your work on the school website. Additionally, as you suggested in your paper, organizing an event that is open to these stakeholders would be a good idea. When people see how engaged and motivated your students are towards the activities in the CS, they would be convinced that it’s worth investing in. In my case, I also explored institutional funding programs that support extracurricular activities within the institution. I wonder if you could also consider this option (and of course, I’d be more than happy to provide advice on how to convince the school!).

It sounds like the CS has a lot of potential. I’m truly excited to see what happens next. Here are some questions for you:

1. How do you see your role in the CS right now, and what roles would you like to take on in the future, either as a group or as an individual LA?

2. What roles would you expect your students, particularly those who keep coming back to the CS, to take on from now on? Do you have any plans to develop a student-initiated project?

Once again, I look forward to seeing its progress in the near future! Thank you for the opportunity to review your work, and please feel free to reach out if you have any questions or require further clarification on any of my comments.

References:

Yamamoto, K. (2023). Taking academic leadership:Reflecting on leading multiple projects as a newbie. In Invited Panel:Finding Grounding through Teacher Communities and Reflection. September 17, 2023. JALT CUE 30th Anniversary Conference. Toyama University.

山本貴恵、川島悠花 (2022) 課外外国語学習に対する意識調査:主体的な学びの促進に向けて [A preliminary report on student’s interest in language learning outside the classroom:

Toward the development of autonomous learners] 和洋女子大学紀要/The Journal of Wayo Women’s University, 63, 103-113.

Hello, Prof. Yamamoto. Thank you very much for your constructive feedback and questions on our paper. We learnt a lot from regular students who came to our Conversation Space (CS) and considered how to develop the CS further. Currently, only I remain in the CS project because Prof. Zoni Upton and Prof. Hill work at different universities.

1. How do you see your role in the CS right now, and what roles would you like to take on in the future, either as a group or as an individual LA?

I invited other teachers, and seven teachers have joined the CS. I’m a facilitator in conversations using board/card games and seek to be an advisor when necessary. I would like to negotiate with the administrators regarding the CS project and set up better circumstances. As we wrote, I really hope to conduct more advisor training sessions for educators and other practitioners who are interested in the project.

2. What roles would you expect your students, particularly those who keep coming back to the CS, to take on from now on? Do you have any plans to develop a student-initiated project?

The CS project is still developing, and in order to design/develop a student-initiated project, more regular students/users would be required. However, as I and Prof. Hill experienced at Meijo University, it would be great if assistant students were invited and let to conduct some social events, including Christmas parties and events to share their learning strategies. In the future, I would like to make the CS open to international students who hope to develop their Japanease abilities and provide regular students with opportunities to socialise with them.