Kevin Clark, Anaheim University

Hayo Reinders, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi

Clark, K., & Reinders, H. (2023). Learning Far Beyond the Classroom: An Exploratory Study of Self-Directed Learning Activities and Strategies of Adult L2 Learners in Japan. Relay Journal, 6(1), 32-57. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/060103

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

There exists a language learning industry in Japan that caters to adult learners. However, a significant number of adults do not engage in such services but rather study on their own. By better understanding this segment of the population, more effective resources can be developed and made available to L2 learners who struggle after they have left formal education. In this study, eight adult learners who engaged in self-directed learning (SDL) were asked to track their learning activities over the course of three weeks by maintaining a language diary. This was followed by interviews to gather information about the reasons behind their choices and the strategies they employed during the activities within the context of the SDL process (Reinders, 2020). The initial results showed that few learners used strategies to enhance their L2 learning, as the resources and activities were often chosen based on reasons unrelated to language learning, such as entertainment. This suggests that they may benefit from some form of guidance to enhance their self-directed learning.

Keywords: self-directed learning, adult learners, learning beyond the classroom, learning strategies

The role of English in Japan is not easily defined due to the historical, political, economic and social perspectives that have affected government policies regarding its implementation in formal education. The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), has launched a number of programs to integrate English into the national education curriculum, including the Japanese Exchange and Teaching Program (JET) in 1987, the Action Plan in 2003 and most recently in 2020 as part of the New National Curriculum Standards development (MEXT, 2018). As a result, every person who has gone through compulsory education in Japan has had experience learning English. This has resulted in a large population of adult learners in Japan who have left formal education but continue to engage in self-directed learning (SDL) to a certain degree. According to the Statistics Bureau of Japan (2021), 12.2% of adults over the age of 25 engaged in English language learning with the majority citing “self-improvement” as the reason.

Despite its enormous size, the population of continuing English learners has often been treated as a single, homogenous group. It is also largely under-researched. Most studies have focused on easily accessible, intact samples of students in classroom settings. Likewise, limited resources and time often force researchers to use controlled experiments that can produce data, which is easier to analyze compared to long-term observational studies. As the majority of academics studying English language learners are themselves engaged in teaching, it is natural for them to choose subjects such as their students or learners attending some type of language learning institution. Much of the research in publications such as TESOL Quarterly and Modern Language Journal is in the form of controlled experiments. Observational studies that focus on adult language learners engaged solely in SDL are exceedingly rare. It is therefore unsurprising that the amount of ethnographic research focusing on Japanese adult learners engaging in SDL is limited. As a result, most advice to learners engaging in SDL is based on the findings of research where the population is still involved in formal learning such as public schools or informal learning such as self-access learning centers. In Beyond the Language Classroom, Benson and Reinders (2011) highlight the complexities of SDL, yet many of the studies described in the book focus on subjects who still access learning institutions. Thus, SDL is often presented based on how it works in parallel with some type of teacher guidance or formal instruction. Many adult language learners lack such guidance or have inadequate knowledge and training that can be applied to their specific situations and often turn to one-point lessons that do not follow a structured learning program encapsulated in popular YouTube channels such as Bilingirl Chika (n.d.) and Hapa Eikawa (n.d.). This highlights the problems adult learners face when they engage in SDL activities once they have left formal education. Many classrooms and textbooks have prepared them to demonstrate their knowledge on exams but have failed to prepare them for further L2 learning through SDL activities (Reinders, 2010; Reinders & Balcikanli, 2011).

The purpose of this study is to explore the aforementioned group of adult learners to gain a better understanding of this heterogeneous population. It aims to identify the types of learning activities they engage in, how they engage in these activities, the reasons and motivations for their choices, and the strategies they utilized within the context of the SDL process (Reinders, 2010).

A Definition of Learning Beyond the Classroom and Its Common Target

This paper adopts the definition of learning beyond the classroom (LBC) as all “types of learning that fall outside of, or extend teacher-led classroom instruction” (Reinders, 2020, p. 2). Specifically, it focuses on learning activities independent of teacher-led classroom instruction in formal learning institutions. Benson and Reinders (2011) identify four dimensions of LBC that are integral to the concept: location, formality, pedagogy, and locus of control. Location encompasses any area where learning takes place outside the main instructed classes including the seemingly ubiquitous extracurricular activities held at schools or attendance to juku (cram schools) in Japan. However, virtual classrooms have added another layer of complexity regarding the delineation of the classroom. They are considered formal learning environments but affect communication in aspects such as body language and flow of conversation compared to physical classrooms. Formality refers to how far independent learning moves away from formal instruction. Casual conversation with friends would be considered less formal than using an application designed to improve one’s vocabulary. Pedagogy in LBC can refer to anything from self-instruction to naturalistic learning. Locus of control refers to who, or what, is deciding the relevant aspects of learning and teaching. This may include a variety of situations for LBC such as learners using self-instructional manuals, which demonstrates locus of control shifting away from the learner but not towards another person, as there is no teacher involved.

The benefits and drawbacks of LBC are detailed in 28 case studies by Nunan and Richards (2015). Authenticity of input and output, authentic interactions, and the development of autonomy are listed as key benefits. However, they add that the time required to produce significant results and high levels of anxiety during face-to-face interactions are barriers that discourage many L2 learners. These results show that even in situations where L2 learners are engaged in LBC activities, they require more guidance to maximize the effectiveness of their efforts. This was also stated in Choi and Nunan’s (2018) studies. Many studies involving LBC investigate the effectiveness of specific activities or new study programs which incorporate formal and instructor-led external assessment. They also tend to look at younger learners who are still involved in formal education and have access to social and academic resources (Bailly, 2011; Sundqvist, 2009).

Self-Directed Learning

The development of SDL

A widely accepted definition of SDL comes from Knowles (1975):

a process in which individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying resources for learning, choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies, and evaluating learning outcomes. (p. 18)

Knowles’ definition and framework of SDL was built upon the work of his predecessor Cyril Houle, a leading researcher in the field of adult education, who published The Inquiring Mind in 1961. At the same time, Allen Tough (1967, 1968, 1971) also built upon Houle’s work to propose several characteristics of adults engaged in self-learning. As subsequent researchers developed this field, new aspects of SDL were taken into account, in particular by Brookfield (1985), who focused on the societal context of learners engaging in SDL. This would eventually lead to diverging models based on the perspectives researchers adopted. Mocker and Spear’s (1982) environmentally determined model, Candy’s (1991) focus on learner autonomy and self-direction, Brockett and Hiemstra’s (1991) Personal Responsibility Orientation Model (PRO), and Garrison’s (1997) model of self-management, self-monitoring and motivation, all offered slightly different perspectives on understanding SDL.

SDL in the classroom has a unique resource that outside-class learning does not, the presence of a teacher. Camilleri (1999) defined the teacher’s role as a manager, resource person and a counselor who can foster the autonomy that is necessary for SDL. Another important point for in-class settings is Benson’s (1997) distinction of learner autonomy (LA) and SDL. Benson states that students may be able to study alone in class demonstrating LA, but gaining skills and knowledge to be able to study on their own is a separate matter, and may lead towards the ability to self-direct one’s learning.

SDL outside of class is often still connected to guidance from instructors or resources provided by a learning institution. Language resource centers (LRCs) or self-access centers (SACs) are available to learners with the aim of fostering autonomous learning (Gardner & Miller 1997, 1999; Morrison, 2008). There are numerous studies of what SDL activities students engage in within such spaces (Benson & Reinders, 2011; Hyland, 2004; Nunan & Richards, 2015; Pearson, 2004) but the majority of them are closely tied to formal education.

The process of SDL

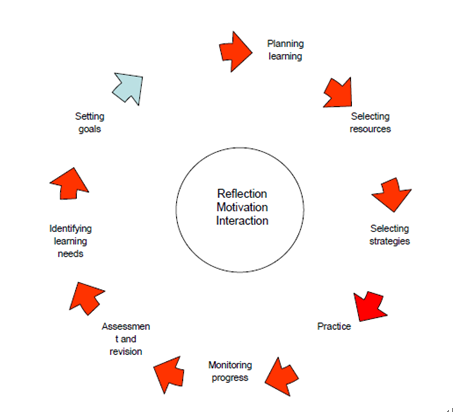

This paper adopts Reinders’ (2010, p. 51) eight-stage SDL process framework as the basis for the theoretical approach and analysis of how the participants engaged in their learning activities. The framework is built upon the cognitive, affective and societal aspects of SDL in the form of reflection, motivation, and interaction as seen below.

Figure 1. Cyclical Nature of the Autonomous Learning Process (Reinders, 2010, p. 51)

This framework involves a cyclical progression starting with identifying learner needs. Learners must identify what they need to improve specific areas of language. This may be done regularly through self-assessment or finding weaknesses after tracking their progress. Then, they must set their language goals to clarify their objectives and identify which materials and activities are most relevant in achieving them. By doing so, planning can commence by choosing the activities and processes that will lead to their goals. This could be challenging for learners who usually depend on teachers, but choosing independently allows for a high degree of customizability. Next is the selection of the appropriate resources that fit within their study plan while taking into account factors including time, finances, and accessibility. These may include authentic materials or even people with whom they can converse.

The next step is for learners to identify and select strategies that are most suitable to their situation and learning style. As Reinders (2010) states, these fall into cognitive, metacognitive, and social-affective strategies. Cognitive strategies are used for direct learning and may include the use of flashcards to memorize vocabulary or summarizing a newspaper article. Metacognitive strategies help optimize the learning process such as keeping a language diary or writing out a study schedule. Social-affective strategies utilize the human resources around learners such as when a learner asks a friend to clarify an idiom or to help with pronunciation. This is followed by the actual practice where learners engage in activities with the target language. Compared to teacher-led activities, SDL activities may have a high degree of freedom in structure and learning process.

During or after the activities, learners monitor their progress. The language diary mentioned above can be used as a simple record or to reflect on any difficulties that arose during the activity. The final step is assessment and revision of the learner’s activities and study program. For example, a learner may take the TOEIC test and then revise the focus of their study program based on the score. This step is crucial as it can affect learners’ motivation and future plans.

Ideally, this cycle is done by learners that have acquired the knowledge and ability to carry out each step without assistance. While not every learner or activity follows this framework perfectly, it can be utilized by students still attending formal learning institutions or as a guide for L2 learners who are no longer involved in formal education.

Methodology

This study used a mixed-methods approach. Language diaries and interviews were used to gather data. The data were analyzed through qualitative and statistical analysis in an effort to triangulate the data and decrease researcher bias when answering the research questions listed below.

- What kinds of self-directed language learning activities do Japanese adult learners of English do and how do they engage in them?

- Which elements of the self-directed learning process do they engage in?

Participants

The participants were chosen based on three criteria: 1) they had left formal education, 2) they were adults over the age of 18 years old, and 3) they engaged in some form of SDL. All known associates of the first author that fit the criteria of the study were asked to participate. To maximize the number of participants, this group was then asked to introduce other people who could participate in the study. Eight participants completed the study: seven females and one male, aged between 26 and 60. All participants graduated from a 4-year university and were working full-time during the study. Their continued English language study in formal learning institutions ranged from another 6 to 10 years after completing the compulsory English language study of junior high school.

Data Collection

The data collected consisted of the participants’ language diaries (via an application) for 3 weeks and interviews conducted with them afterwards. The participants did not keep traditional language diaries. Instead, they were asked to use the Line application to describe and reflect on the learning activities they did right after they finished the activities. They were asked to give four pieces of information after each learning activity: the type of activity, the length of time spent, a short description of the activity, and the reason why they chose it. Daily reminders were sent via Line to remind the participants to record their SDL activities. Additionally, they were given a 5-Likert scale short survey with 1 meaning strongly disagree and 5 meaning strongly agree.

Q1. The activity was helpful for learning English.

1 2 3 4 5

Q2. I would like to learn how to do this activity better so I can improve my English more.

1 2 3 4 5

Each interview was carried out online using Zoom after the 3 weeks of keeping their diaries. A semi-structured format, with a mixture of closed and open-ended questions (see Appendix A for questionnaire) was used. A number of informal starting questions were used as a warm-up for participants to become comfortable speaking English and communicating through video conference. The participants were given a choice of being interviewed in English or Japanese, and all participants chose English. The reason they chose to be interviewed in English despite the difficulty was that they considered the interview an opportunity to practice their English speaking while answering the questions.

Using Reinders’s (2010) SDL process as the framework, questions about the SDL activities aimed to gather data with three main areas of focus using the “Main interview” questions as listed in Appendix A. The first area was the context of their activity choices including reasons and factors that affected their decisions. The second was how participants engaged in the activities. The third was the results of their SDL activities. “General questions” aimed to gather data about how participants reflected on their behavior, their future goals and possible changes they might make. The “Wind up questions” were for feedback about the language diary process and any thoughts participants wanted to share.

The interviews were transcribed and coded through thematic analysis to identify any meaningful text that fell under one of the eight steps of the SDL framework. The data collected from the language diaries were categorized into various themes including activity types, media used, and lengths of activities. Both groups of data were then analyzed statistically and thematically and the final results were tabulated and explained.

Findings

This section aims to answer both research questions. Aspects of the SDL activities including the types, resources, strategies, and the reasons for why the participants chose them are presented. Finally, the participants’ engagement in each step of the SDL process is explained as well as how often each step was utilized. These findings shed light on the participants’ learning environment and give insight into how this affects their SDL process.

RQ1: Japanese adult learners’ self-directed language learning activities.

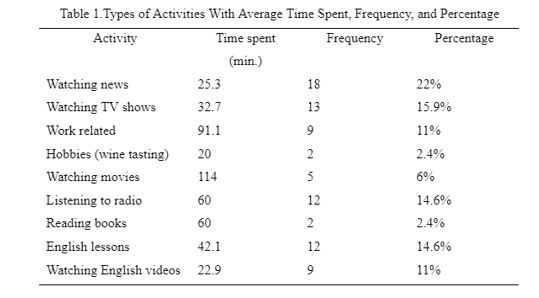

Types of activities. Over the 3 weeks, the number of times participants engaged in activities varied with the lowest being five and the highest being 19. The eight participants recorded a total of 82 activities with an average of 10.25 activities per participant in total, or 3.42 activities per week. The average amount of time spent on each activity was 48.2 minutes, but varied greatly depending on the type of activity. Table 1 shows the types of activities participants engaged in, the average lengths of activities, the frequency, and the percentage among the total activities reported.

The most frequent type of activity was news-related, which included news programs and newspapers, with 18 (22% of all) activities. This had the highest frequency as the participants watched the news as part of their daily routine. Similarly, other routine activities with high frequencies included listening to the radio and watching TV shows. Participants often made little to no effort to actively learn English from these activities.

Activities that focused on language learning included watching videos giving instruction on language, using videos as language learning materials rather than for entertainment, and taking English lessons. As the participants engaged in English lessons based on their mood and circumstances, they were considered similar in nature to the LRCs or SACs available to adults in Japan. That is, the English lessons were a service that participants could utilize rather than being part of their formal education system. These lessons varied in format ranging from informal conversation practice to discussing newspaper articles. Online lessons accounted for 11% while face-to-face lessons were rare making up 3.6%. In addition, the online lessons were chosen for their convenience and price rather than for their quality, as shown in the excerpt below. They used these lessons as a chance to practice their language skills but did not consider a specific goal nor take their language needs into account.

Interviewer: Do you feel like they’re (DMM online classes) pretty useful?

Participant 1: Uh, not pretty useful, but, uh, yeah, I, when I think about the place or a place or what should I say, the place or you know, it’s convenient and cheap. It’s convenient. It’s convenient and cheap. And then, uh, just your, um, yeah. Think about those elements I think it’s, it’s not bad for me.

When activities involving English lessons and English lessons on videos are combined, they account for 21 (25.6% of all) activities. However, only two out of the eight participants engaged in these activities.

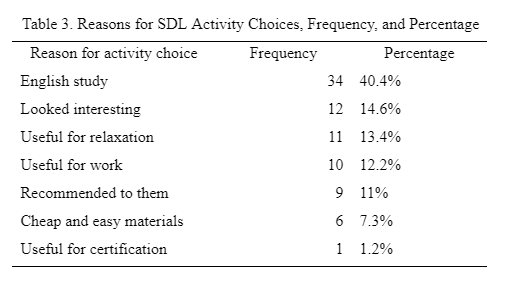

Participants also rated each activity in regard to two points: the helpfulness of the activity and their desire to learn how to engage in the activity more effectively. The overall perceived helpfulness of all SDL activities recorded by participants had an average rating of 3.3. Their desire to learn how to utilize the activities better had an average rating of 2.9. However, these ratings varied depending on the reason the activities were chosen. For instance, activities chosen for English study rated significantly higher than activities chosen for relaxation. See Table 3 for the complete list of reasons for activity choice.

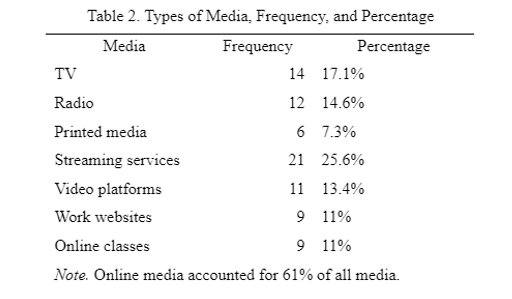

Types of resources. Technology had a large influence on how participants physically engaged in the SDL activities. Participants used the internet to access some form of media for over half of all activities. These included streaming services such as Amazon Prime and Netflix, video platforms such as YouTube, work-related websites and services offering online classes. When online video media including streaming services and video platforms are combined, they account for 32, or 39% of the total SDL activities. Table 2 lists the types of media, the frequency and percentage of their total use.

Participants used the media platform YouTube to watch videos related to English learning (average length of 22.9 minutes) and hobbies (average length of 20 minutes). When they choose videos that focused on language learning, they were shorter in length compared to other SDL activities such as watching TV shows. This is similar to the findings of Umino (1999) who found that L2 learners in Japan used short (average of 20 minutes) self-instructional broadcast (SIB) materials for language learning, as they were easier to incorporate into their schedules. Video materials (39%) accounted for almost half of internet use. Streaming services (accessed through the internet) provided most of these videos. However, one participant did not use any internet-related resources, and if their activities are removed from the tally, 79.4% of all learning activities were conducted through the internet.

Reasons for activity choice. In the language diaries, participants gave brief reasons for why they chose each activity as seen below. Among the eight participants, only two chose their activities for the purpose of language study. They acknowledged that activities chosen for English study were viewed as more relevant for improving their language skills. However, most participants still chose more activities that did not focus on English study and instead focused on enjoyment, relaxation, or content that participants felt was meaningful to them such as environmental documentaries. Table 3 lists the reasons participants chose their SDL activities and the frequency with which these reasons were given.

The interviews gave more detailed explanations about their reasons behind their activity choices. Participants were usually clear about why the activities that “looked interesting” or were “useful for relaxation” were chosen.

Participant 2: Uh, I often watch the dramas in English with Japanese subtitles…Because I, um, the reason why I watch, I’m watching the drama in English is not for my study. Just for my fun.

Another point that highlighted the societal aspects of language learning was the high number of times materials were “recommended” to them by family and friends. Even though the participants did not further talk about the TV shows they had watched, watching TV shows still acted as a springboard for new SDL materials. The participants could receive new recommendations for TV shows from their social group based on the same activity.

Interviewer: Do you ever talk about these TV shows with your friends or anyone?

Participant 2: Uh, no, because I 24 Legacy (TV drama), well, uh, I haven’t talked to about it with my friends, but uh, myfriends, I asked my friends what movie or what drama is good for watching. And then my friend recommended that Chicago Med…And then Amazon, Amazon recommended it, too.

The one participant that chose their activity because it was “useful for certification” (Eiken) did not have any plans to use the certification for work or in the future. This created a situation where the participant had a clear goal for their English while having no motivation to use the certification. It is possible that this situation affected how she engaged in SDL activities.

Participant 3: Uh, uh, CNN News. I just want to improve my English. And, uh, one of my goal is to study English is to pass Eiken grade one…Yeah. I tried twice, but I failed and it’s so difficult and I want, I think I have to, you know, understand the native speakers’ English and it’s so fast, but I have to catch up the speed. So I think the CNN is a good material.

This was in contrast to another participant who chose activities for “English study” as they planned to use their English during their travels to other countries.

As the participants were adults, choosing materials and SDL activities because they were “useful for work” is understandable. Although one participant could access Japanese language journals about their industry, she chose papers written in English. By doing so, she could utilize her English skills while increasing her work-related knowledge.

Interviewer: Do you often read those [research] papers?

Participant 8: Uh, not often, but sometimes I have to, I have to read the reports, related related to the insurance industry…Because I’m working for life insurance company.

Participants mentioned the importance of “cheap and easy materials” when talking about the factors that affected their choice of materials. The free content, variety of choices and the short length of the videos were especially important to one participant that regularly studied English.

Participant 7: Right. So YouTube is about ten minutes, one program, average. Yeah. Well, I can concentrate to certain English, so that’s so it’s, it’s easy to continue every day…So easy. When we watch YouTube it takes about 10 minutes or about 15 minutes. So I can continue studying English almost every day…So I can concentrate.

Interviewer: Usually when you’re learning English, for example, do you have a particular activity you like best?

Participant 7: I think YouTube is the best because, uh, the so many channel for free. Or there are a lot of, uh, the levels for program. So I we can choose, uh, the level of mine. Yeah. I’m not sure, uh, what time what short time every day. But movie takes a lot, a lot. A long time…to watch. It’s fun to study English, uh, well, YouTube, again, again, every day they’re getting better, and then after that once a week, um, a little bit better, my English level is better now.

Many of the SDL activities were chosen to help improve language skills, but 52.3% of the activities were chosen for other reasons such as relaxation and enjoyment, with English study being a secondary consideration. This is similar to Bailly’s (2011) study where the subjects chose “fun” activities like anime and manga when given the option to learn a secondary language with less restriction compared to their school’s foreign language education policy. Our participants seemed to have the same problems as Bailly’s students regarding SDL activities where they had difficulty in choosing suitable learning resources and assessing their L2 progress (Bailly, 2011). Oftentimes, activities and materials were chosen by our participants based on factors unrelated to learning needs as shown in Table 3.

Strategies. In regard to the engagement of learning strategies, the strategies mentioned by the participants fall under cognitive, metacognitive, and social-affective. Only two of the participants utilized social-affective strategies. The other six participants engaged in SDL activities alone or did not approach others for help.

Cognitive strategies such as the use of L2 subtitles were mentioned by every participant, which is understandable considering their ease of use and ability to clarify. However, L1 subtitles were used by half of the participants for further clarification or to enjoy the activity rather than to study. Other cognitive strategies mentioned included repeatedly watching the same video for better listening comprehension, using online dictionaries as support tools for unknown phrases and slang, and reading materials aloud to check pronunciation. Seven of the participants spoke about taking notes. However, being aware of what they should do did not indicate that they actually did so.

Participant 1: Uh, so I used to take notes, but I don’t do it now. Yeah. It’s been too many things. Yeah, right. So, uh, I gave up…Um, maybe I need to, um, I need to learn more vocabulary, expand more vocab my vocabulary, like the vocabulary or the book or textbook or something and, and broad, my vocabulary, and then read the newspaper. I think I should do so, but, hmm.

Several metacognitive strategies were mentioned in the interviews indicating that the participants were generally aware of how to improve the effectiveness of their SDL activities. One participant indicated they went to bed early to be in better condition for learning. Another participant chose a movie she had seen before that would allow her to enjoy both the entertainment aspect as well as the language to boost her motivation. In addition, materials were sometimes chosen based on a particular study style such as the short YouTube videos that did not require a lengthy investment of time as mentioned previously by Participant 7.

The social-affective engagement of the participants came in two forms. One was the simple interaction when they were recommended or asked their friends for materials such as videos or movies. The second was when they interacted with people outside of friends and family to create learning opportunities or to enhance their understanding. The first type of social-affective engagement ended once the information was acquired. However, the second type was an integral part of the learning experience. One participant even went to bars to engage in conversation with native speakers in order to practice what they had learned.

Interviewer: How did you decide these [study] techniques?

Participant 7: Uh, so, and then, you know, I often go to the bar. Yeah. So when I knew, when I talk to international friends, I try to use the word when I learn from the listening. And ask if it’s correct…Try to use it in real conversation.

It should be noted that this participant did not go to a bar during the timeframe of the study and was thus not included in the SDL activities. However, we felt it was worth including this information as it was mentioned during the interview as one part of his learning strategy. This participant was also one of the three participants who utilized a multi-layered approach when dealing with a difficult part of an activity. These included actions such as checking the subtitles, making notes, asking acquaintances for information about the subject, and mentally preparing for future encounters with it.

Interviewer: If you’re watching the movie and there’s some parts you don’t understand what words you can’t catch, what do you do?

Participant 7: I tried to, uh, check the subtitle. And, uh, what write down write down on paper…So I ask my friend the pronunciation or word and, uh, the reason why, yeah. Then I try to catch next time.

Motivation, or lack thereof, was a key factor in how participants engaged in SDL activities. Six of the participants expressed a dislike of activities that caused stress or avoided activities they considered too time-consuming. In addition, the participants that reported a lack of motivation to check unknown vocabulary or phrases were among these six. Yet, motivation has been shown to greatly influence L2 learners in many ways including their attitudes toward learning, level of L2 mastery, and learning styles (Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2009, 2013; Ushioda, 2010, 2014).

RQ2: Elements of the self-directed learning process participants engaged in.

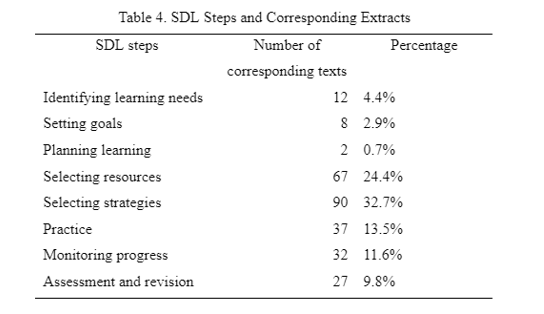

There were 267 extracts identified from the interviews pertaining to the steps in Reinders’s (2010) SDL framework. They are listed in Table 4 with the number of corresponding extracts.

Twelve extracts (4.4%) fell under “Identifying learning needs,” which usually related to the participants’ work or a specific issue they were aware of. For example, Participant 4 expressed a learning need in regard to pronunciation. In addition, she understood that it would require external help unlike her vocabulary practice, which could be done alone.

Interviewer: If you had more time, would you change the way you study?

Participant 4: Um, yeah. If I had enough time, to learn the pronunciation. Yeah.

Interviewer: Add pronunciation practice?

Participant 4: Only pronunciation.

Interviewer: Okay. Okay. Why is that?

Participant 4: Uh, so it’s the listening practice speaking practice vocabulary practice I can do by myself. Pronunciation to, pronunciation needs check by the someone.

Only three participants set goals, and these goals were often vaguely defined. As seen in the excerpt below, the participant could visualize herself using the language, in line with Dörnyei’s concept of ideal self (2009), but clearly specified goals were rare. They did not set their goal until after they had visualized themselves using English to communicate in a specific situation. Just eight extracts (2.9%) fell under “Setting goals.”

Interviewer: Do you have any goals for your English?

Participant 5: Goals? No goals actually. I just want to learn, to communicate with people overseas when I, yeah, especially, I like traveling abroad…Yeah. So I want to communicate the local people. Yes, that’s why English? Yeah. The English is yeah, common language…That’s why I’m learning I have been learning English. That’s maybe that’s my goal.

Only two extracts (0.7%) fell under “Planning learning” when the participants mentioned focusing on English study. Participant 4 attempted to set time aside regularly, two to three times a month, to practice speaking when taking a private lesson. Participant 5 read the book, both in English and Japanese, before watching the movie it was based on as seen below. However, as activities were most often chosen based on convenience, low cost, recommendations, interests, or for relaxation, prior preparation and planning were rare and did not seem to be the priorities.

Interviewer: Do you do any sort of preparation before you watch these movies?

Participant 5: Hmm, yes, actually I had the book about…

Interviewer: Go ahead. So you read the book already?

Participant 5: Yes.

Interviewer: Okay. Okay. In English?

Participant 5: Um, in English and Japanese.

The 67 extracts (24.4%) in “Selecting resources” and the 90 extracts (32.7%) in “Selecting strategies”accounted for more than half of the texts from the interviews that were identified through thematic analysis. The participants did not demonstrate much planning, but were fairly conscious of how to utilize learning strategies once they had chosen the materials. As seen below, the participant chose to re-listen to a specific part because she found it interesting and believed it could be useful.

Interviewer: Why did you choose [The Holiday]?

Participant 7: Uh, I know the movie, uh, British English and American English, so it’s, uh, at the same time I can learn, uh, British English and American English.

Interviewer: If you’re listening to it and there’s some English you don’t understand, for example, do you try to listen to it again? Or is there any special technique you use?

Participant 7: Sure. If it’s it was drama or something like that, or comedian that at the time, like, I not usually, but I sometimes go back to listen English because it’s quite funny saying or it’s, uh, useful maybe.

The final three parts of the SDL framework accounted for roughly one-third of the interview extracts. Thirty-seven extracts (13.5%) fell under “Practice.” The participants were asked to give more information about SDL activities recorded in their language diaries. For instance, one participant chose to read reports related to her industry in English rather than in Japanese and explained how she incorporated this activity into her work.

Interviewer: So what is that for? Do you often read those papers?

Participant 8: Because I’m working for an insurance company. A global company headquartered in Hong Kong. So…I have to make a report…Comparing to the global trend. So at that time I have, I have to take the report, the report materials about the global trends and then I, I will make a report…By myself.

The 32 extracts (11.6%) under “Monitoring progress” and 27 extracts (9.8%) under “Assessment and revision” indicate that either the participants made less effort for these steps or were unsure about how to complete them. They seemed to struggle to define how they measured or assessed their progress. The participants would give vague descriptions about their L2 progress with little evidence because they did not have a self-assessment system or tool. Their judgments were based on feelings and impressions with the hope that they were making progress. Participant 1, for example, is not sure whether the online class was effective or not.

Participant 1: I think speaking, speaking, what should I say, I have speaking ability, probably speaking ability. I hope the speaking ability is is getting better after that class. Yeah…Each class. That’s my hope. I’m not sure, yeah, it works or not, but, uh, that’s my hope.

When our participants talked about improvements in their language, they usually referred to vocabulary. However, their assessment of their vocabulary improvement was vague and sporadic. Also, they were under little pressure to produce results because they were not required to show proof of their progress. This lack of pressure seemed to be one factor in how little they monitored and assessed their language improvement. Revision usually consisted of re-watching materials rather than revising their study program.

Interviewer: When you watch [Friends], after you watched the show, do you feel like your English got better in some way or like you changed?

Participant 8: Uh, I, I don’t feel any progress…But the, no, but yeah, I just try to listen and I hope it works, but, um, uh, I don’t feel any changes. Yeah. Just, uh, just for 20 minutes or 30 minutes. Yeah. I hope it accumulate little by little.

Interviewer: Do you still feel like it was useful or do you still feel like you learned something?

Participant 8: Uh, it’s depends on the story…I want to watch it again. Try to catch up…Yeah. Try to study every day. If I have time I try to again. That’s why I study English every day.

The participants focused more on choosing materials and using strategies compared to other steps. However, they did not make much effort in checking unknown vocabulary from using their chosen materials for example, which seemed to hinder their progress. Participant 3, for instance, admitted that she just used Japanese subtitles when watching English movies and did not try to improve her listening skills and vocabulary at all, as shown in the extract below.

Interviewer: When you were watching the movie, were there any parts that were difficult to understand?

Participant 3: A lot of, uh, parts. Uh, I, there, there are lots of parts I couldn’t understand, but I watched it with some Japanese subtitles so I didn’t care. I didn’t care.

The high number of texts found through thematic analysis that corresponded to the stages of “Selecting resources” and “Selecting strategies” suggests that participants were engaged primarily in the choices and activities themselves rather than the guiding aspects or specific, long-term goals of L2 learning. This can be seen from the three stages least mentioned by the participants: “Identifying learning needs,” “Setting goals,” and “Planning learning.”

It is likely that not all of the points mentioned above are characteristics shared by the entire adult L2 learner population in Japan. However, this study did show that none of the participants could demonstrate the complete SDL process, thus, indicating a need for better education for adults wishing to continue their L2 learning outside of formal learning institutions.

Suggestions and Conclusion

This study aimed to give insight into the circumstances of adult L2 learners in Japan. First, their choice of materials is often based on factors other than their perceived learning value, such as time limitations and the level of enjoyment they can expect. This freedom means that adult L2 learners often choose materials that are authentic in nature due to their practicality or entertainment value. However, freedom implies lack of guidance, which can lead to such learners not developing a comprehensive and structured study program, such as one that follows Reinders’s SDL process model. This is further exacerbated by a lack of clear self-assessment not enabling them to see their progress in their L2 learning which can affect learners’ motivation when engaging in SDL activities.

Unlike the participants in studies that investigated students’ activities outside the classroom (Bailly, 2011; Sundqvist, 2009), the participants of this study did not have guidance about learning strategies, advice about materials choices, or a study plan designed by instructors. Our participants made choices about materials and activities that reflected these differences, such as prioritizing materials useful in their work or choosing activities based on enjoyment first and learning value second. It appears from our study that adult L2 learners in Japan can be truly alone when engaging in SDL activities. It is therefore incumbent upon us researchers and teachers to give more attention to preparing learners for their future learning.

It can be said, therefore, that adult L2 learners require knowledge and training to effectively engage in SDL. They need self-assessment abilities and the ability to identify their learning needs among other skills. Based on our study, many adult L2 learners have not had the opportunity to gain this knowledge when they were still involved in formal education, or they may have forgotten it. Therefore, we recommend that pedagogical and practical skills of SDL should start in the classroom. With training in the SDL process including learning strategies and useful resources, teachers could help students develop autonomy and increase their confidence when they engage in SDL. For example, teachers could show students different approaches of studying when using the same in-class materials. One approach could focus on vocabulary learning while another could focus on summarization skills. In addition, they could give suggestions for alternative materials that could be utilized with the same approach such as movies or songs. If teachers introduce Reinders’s SDL model in class, students could use the template to understand the fundamentals of how to design a study program that could be used after leaving formal education.

Many of the participants used technology in their SDL activities. Technology plays an important role as both a support tool for language learning and as a resource for choosing materials. Yet, the nearly endless choices of materials online may be overwhelming for learners when they engage in SDL activities, causing them to stay within a comfort zone. In addition, they may lack the knowledge of how to utilize such materials effectively without guidance highlighting the importance of technology literacy for L2 learners. Again, teachers could give students a list of useful online resources such as news sites, educational YouTube channels, and free books (see Appendix B for a list of suggestions).

Social resources can help L2 learners create more networks and communities to support each other. Both teachers and students should work together to facilitate these support groups with teachers setting up the structure and students contributing to their development. For example, setting up a foreign language club can provide a place where students can come together to share ideas about how they learn and to practice the language in a more casual setting. The members could elect a leader to maintain the structure and the teacher could give guidance and advice when needed. Such a club would allow the members to work together in exploring and developing their own SDL style while having access to a teacher.

Limitations

This study aimed to understand a particular group of L2 learners in Japan. However, the sample size was small and imbalanced as there were seven females and only one male. This may have affected the external validity of the findings. In addition, the participants were chosen based on the simple criteria of being adults who were engaged in some form of SDL and no longer engaging in formal learning. Thus, there is a wide range of circumstances among the participants. The length of the observation period was only three weeks, and the data gathered during that time was limited. This was inevitable as the language diary was designed to influence the participants’ activities as little as possible. Also, there was a possibility that some of the participants did not record all their SDL activities. This was because they believed that certain activities were only for fun and thus did not count as SDL activities. The daily reminders about the language diaries also affected certain participants and made them feel pressured to study even though they were told to act naturally.

The interviews were conducted only once and in English. Although the participants were offered to have the interview conducted in their L1, they chose English because they wished to practice their speaking skills, which may have limited their ability to express their thoughts. Finally, the interviews were kept to less than 90 minutes in consideration of the participants’ schedules. However, this also limited the amount of data that could be collected about the SDL activities.

Notes on the contributors

Kevin Clark completed his MA in TESOL at Anaheim University in 2022. He started tutoring from JHS which led to teaching various levels in Japan after graduating university. His research interests include adult L2 learners and SDL.

Hayo Reinders has a PhD in Applied Language Studies & Linguistics from the University of Auckland and is currently a TESOL professor and Director of Research at Anaheim University, Senior Research Consultant at Kanda University of International Studies, and Professor of Applied Linguistics at KMUTT University. He is a leading figure in the field of TESOL and has published numerous books and articles on SDL.

References

Bailly, S. (2011). Teenagers learning languages out of school: What, why and how do they learn? How can school help them? In: P. Benson & H. Reinders (Eds.), Beyond the language classroom (pp. 119-131). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230306790_10

Benson, P. (1997). The philosophy and politics of learner autonomy. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 18–34). Longman. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315842172-3

Benson, P. & Reinders, H. (Eds.), (2011). Beyond the language classroom. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230306790

Bilingirl Chika. (n.d.). Home [YouTube channel]. YouTube. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/user/cyoshida1231/featured

Brockett, R.G., & Hiemstra, R. (1991). Self-direction in adult learning: Perspectives on theory, research, and practice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429457319

Brookfield, S. (1985). Self-directed learning: a conceptual and methodological exploration. Studies in the Education of Adults, 17(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.1985.11730445

Camilleri, G. (1999). Learner autonomy: The teachers’ views. Council of Europe.

Candy, P. C. (1991). Self-direction for lifelong learning: A comprehensive guide to theory and practice. Jossey-Bass. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.29-4017

Choi, J., & Nunan, D. (2018). Language learning and activation in and beyond the classroom. Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1(2), 49-63. https://doi.org/10.29140/ajal.v1n2.34

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9–41). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847691293-003

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2009). Motivation, language identity and the L2 self. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847691293

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2013). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833750

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1997). A Study of tertiary level self-access facilities in Hong Kong. City University.

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. Cambridge University Press.

Garrison, D. R. (1997). Self-directed learning: Toward a comprehensive model. Adult Education Quarterly, 48(1), 18-33. https://doi.org/10.1177/074171369704800103

Hapa Eikaiwa. (n.d.). Home [YouTube channel]. YouTube. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/c/Hapaeikaiwapage/featured

Houle, C. O. (1961). The inquiring mind. University of Wisconsin Press.

Hyland, F. (2004). Learning autonomously: Contextualizing out-of-class English language learning. Language Awareness, 13(3), 180–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410408667094

Knowles, M. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Follett Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1177/105960117700200220

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT). (2018). Shougakko gakushuushidouyouryou kaisetsu gaikokugo-katsudou/gaikokugo-hen [Explanation of the course of study for primary school: Foreign language activities and foreign language]. https://www.mext.go.jp/component/a_menu/education/micro_detail/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2009/06/16/1234931_012.pdf

Mocker, D.W., & Spear, G.E. (1982). Lifelong learning: Formal, nonformal, informal, and self-directed. ERIC Clearinghouse for Adult, Career, and Vocational Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001848183033004009

Nunan, D., & Richards, J. (Eds.). (2015). Language learning beyond the classroom. Routledge.

Pearson, N. (2004). The idiosyncrasies of out-of-class language learning: A study of mainland Chinese students studying English at tertiary level in New Zealand. In H. Reinders, H. Anderson, M. Hobbs, and J. Jones-Parry (Eds.) Supporting independent learning in the 21st century. Proceedings of the inaugural conference of the Independent Learning Association, Melbourne AUS (pp. 13-14). Auckland: Independent Learning Association Oceania. https://docplayer.net/22480303-The-idiosyncrasies-of-out-of-class-language-learning-a-study-of-mainland-chinese-students-studying-english-at-tertiary-level-in-new-zealand.html.

Reinders, H. (2010). Towards a classroom pedagogy for learner autonomy: A framework of independent language learning skills. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 35(5), 40-55. http://ro.ecu.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1454&context=ajte

Reinders, H. (2020). A framework for learning beyond the classroom. In M. Raya, & F. Vieira (Eds.), Autonomy in language education: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 63-73). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429261336

Statistics Bureau of Japan. (2021). Reiwa 3nen shakaiseikatsu kihon chousa [Reiwa 3rd year: Survey on time use and leisure activities]. https://www.stat.go.jp/data/shakai/2021/pdf/gaiyoua.pdf

Sundqvist, P. (2009). Extramural English matters: Out-of-school English and its impact on Swedish ninth graders’ oral proficiency and vocabulary [Doctoral dissertation, University of Karlstad]. Digitala Vetenskapliga Arkivet. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:275141/fulltext03.pdf

Tough, A. (1967). Learning without a teacher: A study of tasks and assistance during adult self-teaching projects. Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Tough, A. (1968). Why adults learn: A study of the major reasons for beginning and continuing a learning project. Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Tough, A. (1971). The adult’s learning projects: A fresh approach to theory and practice in adult learning. Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/58.7.914

Umino, T. (1999). The use of self-instructional broadcast materials for second language learning: An investigation in the Japanese context. System, 27(3), 309–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(99)00027-5

Appendix A

Interview Questions

Interview started with greetings, a thank you for their cooperation and restating the fact that they would be recorded for transcription and analysis later.

Starting questions:

How was the experience of the language diary?

Was there anything you noticed during the three weeks?

Main interview (use 2-3 entries as main focus for the questions):

Background questions about language diary entries-

Did you watch it alone?

Listen to it while you did something else?

Read it as a way to relax? If not, why not?

Do you prefer doing this kind of activity alone or together with someone?

Do you think you improved in some way? If so, how? If not, how could you?

Do you think you still remember what you learned? If so, how?

Do you try to focus on anything in particular?

How did you prepare before you started?

Why did you choose this activity?

Was there anything difficult about it?

How did you deal with it?

Did that work well for you?

Are there other ways you usual deal with such difficulties?

What else did you try to do?

General questions:

Are there any other activities that you engage in besides these?

What kinds of activities do you prefer? Or dislike?

Does time or level of the English affect your activity choices?

Which type of media do you prefer to use when you study? Internet? Videos? Books?

How useful do you think these ways of learning are for you?

How do you think you could improve those?

Would you change the way you study now?

Where did you learn these techniques?

Where do you go for help?

If you want to improve more, where do you go or what do you do?

If you had more time, would you change the way you study?

If you were to give advice to a new learner, what would you say?

Do you have any goals for your English at this time?

Wind up questions:

Is there anything you would recommend about the format of the language diary or the way the data was collected?

Is there anything you want to add?

Appendix B

Helpful Online Websites

News sites

Educational YouTube channels

https://www.youtube.com/@BBCEarthKids

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCsXVk37bltHxD1rDPwtNM8Q

Free books

I was delighted to read your paper, which addresses what is I believe a very important and under researched area. A few years ago, working with teacher and learning advisor colleagues, I established a component within the compulsory English program at our university (the ‘Self-Directed Learning Unit’) which aims to prepare students for lifelong language learning. This unit broadly follows the cyclical process you describe (Reinders 2010) and has proved popular with students who have consistently evaluated it as useful and engaging. I believe SDL should be an integral component of all university (and school) language classes and should not be treated as a niche concern, associated with “motivated” learners and left to self-access centers and/or learning advisors to deal with. In my own research I have been examining learner agency in the context of our self-directed learning unit. However, we cannot follow or predict what will happen after participants leave university so it is very useful to learn about what those engaged in learning beyond the classroom as older adults think, feel, and do in respect of their language learning.

It was particularly interesting to note that the learners in your study seemed not to focus sufficiently on planning and evaluating. Planning, reflecting, and self-assessing are all important aspects of SDL and we include explicit focus on them in our unit. However, reading your paper several questions occurred to me, which echoed our own problems in administering the self-directed learning unit. They are not intended as criticisms, and I don’t have any answers to them but I thought I would share them with you for possible consideration or discussion.

• To what extent do language learning goals need to be explicitly articulated to self or others? Many of our students express a sense that they want to be able to communicate with people from other countries (which seems to correspond to want Yashima (2013) identified as “international posture”). But this seems to be more of a feeling or disposition than a concrete “goal”. I think what learners engaged in SDL require are not so much goals as learning objectives, in which case I guess we are talking more about planning. Language is part of the problem here and the complexities further increase when we are dealing with multiple languages (our students tend to plan and reflect in Japanese).

• Can we assume that adult learners are motivated by / directed towards improving their English proficiency? I feel that the paper may contain that assumption and perhaps all that we do as language teachers depends on it. But maybe they just enjoy the activity and don’t care about proving even to themselves they are getting better at it. This reminds of my own experience of studying French in the UK as a young adult by attending evening classes at a local college. I had complex motivations for engaging with French even though I had no immediate plans to visit France or opportunities to use the language. I thoroughly enjoyed the class for one semester because it was intellectually stimulating and afforded a chance to hang out with people I wouldn’t normally meet. However, in the second semester it was determined that in order to justify the program funding we had to demonstrate our competence in the language. This meant me focusing on building a portfolio of evidence for a qualification which was at a lower level than one I already had from school. The learning stopped, the fun stopped, the teacher was embarrassed, and some of my classmates quit. The only reason I persevered was because I liked the teacher and I realised dropping out may have negative implications for the viability of the program and thereby her ongoing employment. A completely ridiculous situation and an experience that has always stayed with me as a language teacher and learner.

These problems do not, of course, undermine your claim that people should be better supported while in school/university so they understand and can apply approaches to self-directed learning that are most likely to result in effective language learning. This knowledge should provide them with agency to interact with language and language learning however they see fit, including in ways we might not recommend.

Finally, I realise that what I have said so far is of a rather philosophical nature and may be of limited value in helping you revise the paper as a text, so I’ll end with a few more focused comments. Firstly, I felt that the paper covered a lot ground, sometimes a bit too quickly – there are a lot of extracts but perhaps some don’t add much to what you have already mentioned in the text. You might think about cutting down the total number of extracts and exploring the ones you do include in a little more detail. Secondly, I would appreciate a little more demographic detail about the six participants as well as an explanation of the positionality of the researcher(s) and your respective roles in the data collection / analysis. Thirdly, I was a bit confused by the part about goals. You mentioned that students rarely referred to goals but I the extract you included Participant 5 was specifically asked about their goals. Was this the case for all participants? Finally, a related issue is the procedure you used for categorising and quantifying the extracts. It strikes me that this must have been challenging as there must have been some overlap between categories. It might be helpful to include some discussion of this either during the methodology section or in the limitations.

Thanks for a very stimulating paper and all the best with your research.

Thank you for taking the time to read through the paper and for your insightful comments. I also agree that this area of research has much greater potential yet to be explored. By incorporating new findings into the current education system, it could potentially shift students’ perspectives towards lifelong language learning for future generations. Looking at the findings of this paper, it seemed that many people who have left formal education are not fully equipped to purse language learning autonomously.

As you mention, planning and evaluation were two of the weakest aspects of language learning that the participants displayed. The blurring of boundries between goals and learning objectives may be impossible to clearly distinguish as they can overlap while being integral to one another. Much the way one aims to complete a marathon with the intent of becoming healthy, language learners often aim to achieve a particular test score in order to communicate better with others. It is true reaching one’s goal may not fully reflect one’s learning objective. Your experience of learning French for enjoyment and intellectual stimulation rather than for the explicit purpose of communication is particularly pertinent. Learning objectives may be more applicable for adult language learners who have a more nebulous goal. Indeed, one of my students is an 80-year-old woman who enjoys the social interation of communication more than the challenge of learning. It is true that many language learners are forced to do display their improvement in language proficiency while enrolled in formal education systems, but it is my hope that more students will be taught how to effective engage in autonomous language learning should they wish to do so in the future.

I can understand how some parts of the paper were spread a bit thin. As the subject itself is quite broad, I worried about overlooking any relevant parts. Many of the extracts were included for an illustrative purpose leaving less room for in-depth explanations. I will try to parse that down and include more details for the ones left. As for the demographic information of the participants, I am not sure as to what additional information should be included. I will add additional information regarding the positionality of the researcher. Regarding the mention of goals, each participant was asked about their goals, but few explicitly defined them with most mentions being vague in nature. Participant 5 was included as an illustration of this phenomenon so I will clarify this in the rewrite. Finally, your advice about the procedure for categorising and quantifying the extracts is much appreciated and duly noted.