Haruka Ubukata, Kanda University of International Studies

Ubukata, H. (2024). Exploring a Novice Advisor’s Beliefs on Advising. Relay Journal, 7(1), 4-29. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/070102

[Download paginated PDF version]

Abstract

This self-study investigated advisor beliefs in Advising in Language Learning (ALL). The research aimed to examine what beliefs are observed in a novice advisor’s reflection entries. From the data analyzed, four types of beliefs were observed: beliefs about advising, beliefs about learners, beliefs about learning, and beliefs about advising as a profession. Beliefs about advising accounted for the majority, and several themes emerged within the category, including advisor role, advising strategies, purpose of advising, tools, and language use. The results are discussed in relation to advisor characteristics identified in the learning trajectory for advisors (Kato & Mynard, 2016) as well as other relevant aspects of ALL.

Keywords: Advising in Language Learning (ALL), advisors’ beliefs, reflection

Advising in Language Learning (ALL) is an area of practice and research that has recently attracted a high level of interest in the field of self-access learning (Mynard, 2022). It has been studied from a range of aspects, including its dynamic and complex nature (e.g., Castro, 2019), how it supports learners’ development (e.g., Shelton-Strong, 2022a, 2022b) as well as advisors’ professional development (e.g., Kato, 2022; Sampson, 2020). As an evolving field, however, continued research is essential to better understand and utilize its practice.

The purpose of this study is to contribute to the understanding of ALL by exploring what types of beliefs a novice advisor may hold, shaping their advising practice. Although existing literature documents advisors’ experiences and development to some extent, few studies systematically analyzed advisors’ beliefs in ALL to my knowledge. I attempt to start filling this gap by analyzing the beliefs that emerged from my own advising reflection from the first year of being an advisor in this study. In this article, I will first provide some background by covering literature on teachers’ beliefs, ALL, and beliefs of advisors documented in previous research. I will then describe the research methodology and present findings with discussion. Finally, I will conclude the article by addressing the limitations of the study as well as prospective research directions on advisors’ beliefs in the future.

Literature Review

Teachers’ beliefs

The concept of beliefs can be summarized as “a proposition which may be consciously or unconsciously held, is evaluative in that it is accepted as true by the individual, and is therefore imbued with emotive commitment; further, it serves as a guide to thought and behaviour” (Borg, 2001, p. 186). Teachers’ beliefs are suppositions held by teachers, of relevance to their profession, including teaching, learning and students (Ferguson & Lunn, 2021). They have been studied extensively, and the areas of inquiry include the conceptualization, the relation between teachers’ beliefs and teaching practice, and development of teachers’ beliefs (Fives et al. 2019). Past studies have indicated that teachers’ beliefs are a significant factor that affects teachers’ decision-making and actions in their classrooms (Barcelos, 2016) and play a central role in their professional development (Richards et al., 2001).

A number of characteristics have been identified to understand the complex nature of beliefs. One characteristic is that they are dynamic and socially constructed. It is suggested that, while beliefs may affect teachers’ practice, classroom experiences can also influence and modify their beliefs (Sakui & Gaies, 2003). At the same time, the process of teachers’ implementing their beliefs is complicated, facilitated or hindered by a range of internal (i.e., within a teacher; e.g., knowledge, other beliefs) and external (i.e., of their surrounding environment; e.g., school policies, class size) factors (Buehl & Beck, 2014). Teachers’ beliefs are also context-driven and “can vary or remain stable across time and space, and even be mutually conflicting” (Kalaja et al., 2016, p. 10). In addition, research seems to suggest that some beliefs are more changeable than others (Hampton, 1994). Core beliefs, which are central in one’s belief system, as opposed to peripheral beliefs, tend to be more stable and more resistant to change (Gabillon, 2012). Furthermore, teachers’ beliefs may be derived from different sources, including teachers’ own experience of language learning and teaching, established practice at their institution, their personality and their preferences, their understanding of education- or research-based principles (Richards & Lockhart, 1994).

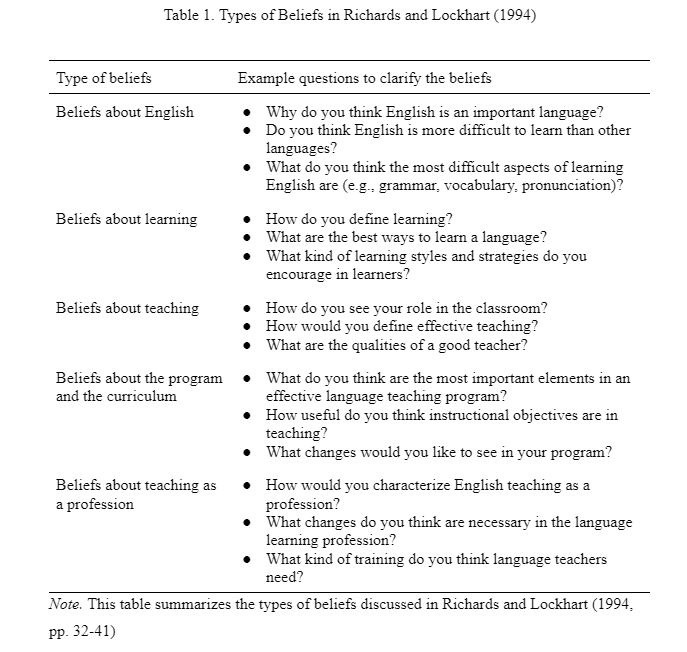

There are different types of beliefs that are at play in teaching. Table 1 summarizes Richards and Lockhart’s (1994) classification and example questions they provided to illustrate what specifically teachers can ask themselves to explore those beliefs. First, beliefs about English are concerned with teachers’ views on different aspects of the language they teach, ranging from its role in society to what makes it difficult to learn the language. English may be replaced with any other languages, depending on the target language. Second, beliefs about learning address teachers’ expectations as to the learning process. Teachers may have different views on what should be learned as well as how it will be learned. Third, beliefs about teaching are about “what constitutes effective teaching” (Richards & Lockhart, 1994, p. 36). For example, the role they play as teachers, the qualities they seek in good teaching, and the kind of resources they find effective. Fourth, beliefs about the program and the curriculum address teachers’ beliefs on different aspects of their teaching setting, including course objectives, assessment, and teaching materials. Teachers may also have specific beliefs regarding the programs in which they teach at their institutions. Finally, beliefs about teaching as a profession are about teachers’ sense of professionalism. This essentially concerns a bigger societal context as it can be greatly affected by such elements as the working conditions and career opportunities available in their society.

Advising in Language Learning (ALL)

ALL is “an intentional dialogue whose aim is for the learners to be able to reflect deeply, make connections, and take responsibility for his or her language learning” (Kato & Mynard, 2016, p. 2). It typically takes place in a one-on-one session outside the classroom, where an advisor and a learner co-construct a dialogue centered around the individual learners’ needs rather than following a set curriculum (Mynard, 2019). The central nature of ALL is Intentional Reflective Dialogue (IRD), defined as the dialogue “structured intentionally to promote deeper reflection” (Kato & Mynard, 2016, p. 6; emphasis in original). It is through the IRD that an advisor approaches learners with individual needs and interests, addressing issues related to language and learning skills (e.g., how to improve test scores, how to practice listening skills) and/or those related to affective factors (e.g., anxiety, motivation; Kato & Mynard, 2016). In this section, I will introduce how advisors support learners by engaging in a dialogue and using a variety of strategies and tools.

ALL in practice. An advisor is usually qualified as a language teacher, working as a full-time advisor or juggling teaching and advising in many cases. In ALL, an advisor supports a learner to “define their needs, formulate learning goals, reflect on strategies for achieving these goals, monitor and evaluate learning outcomes and the learning process, and make decisions for further learning” (Tassinari, 2016, p. 77) through IRD. As an advisor needs to pay attention to cognitive, metacognitive, and affective aspects of language learning in this process, they need to be equipped with a wide range of knowledge and skills (Kato & Mynard, 2016). They need to be familiar with language learning strategies as well as resources available in the learners’ learning environment, and advisors also need to possess skills to hold learner-centered, empowering advising sessions (Stickler, 2001). At the same time, an advisor needs to be ready to deal with a learner’s positive and negative emotions (e.g., satisfaction, interest, frustration, fear) that accompany their learning, which may be present throughout the dialogue (Tassinari & Ciekanski, 2013).

One challenge an advisor often faces is to discern how direct they should be with their learner (Carson & Mynard, 2012). Providing a learner with opportunities to experiment and reflect can increase the likelihood that they learn to take more control over their learning process (Mynard & Thornton, 2012). For this reason, while an advisor has expertise in language learning, they typically avoid giving direct suggestions. An advisor encourages a learner to explore their thoughts by asking reflective questions and to seek their own answers. However, at the same time, they also need to be ready to offer suggestions drawing on their expertise where necessary (Carson & Mynard, 2012). For learners who are not aware of their learning process and are not benefiting from subtle, indirect interventions, an advisor may instinctively employ a more directive approach (Mynard & Thornton, 2012).

Another issue that concerns ALL is the language used in the dialogue. Advising sessions may be conducted in a learner’s first language (L1) or target language (TL) for different reasons, including the institutional policy and a learner’s preferences. In an attempt to understand this aspect of advising sessions, Thornton (2012) conducted a study to interview advisors from different institutions, investigating their experience with L1 and TL advising sessions. Findings showed that in TL sessions, the advisors often needed to be patient with the slow pace, especially with lower proficiency students as they might not be able to process information or organize ideas as quickly or precisely as in their L1. Thornton’s participants commented that having a structure (e.g., integrating advising as part of a course; advisor taking control of the agenda during a session) would lead to successful TL sessions. Furthermore, motivation was found to be a major advantage that the participant advisors acknowledged in TL sessions. They believed that a learner would feel a sense of achievement when they succeed in discussing such a complex matter as language learning in their TL. At the same time, however, all the advisors had experienced frustration or witnessed their learners experiencing it due to communication hurdles in using TL. Regarding the use of a learner’s L1 in advising sessions, the advisors highlighted its usefulness. Ease of communication was the most commented advantage. Although using a learner’s L1 can pose challenges to advisors who do not share the same language, L1 advising sessions were generally considered “smoother” (Thornton, 2012, p. 76). In addition, some of the participant advisors noted the positive impact of using L1 on building rapport with a learner. They felt learners could relax when they used their L1. One of the advisors also mentioned that using L1 made them feel like they were more approachable.

ALL strategies and tools. In order to promote reflection, an advisor actively listens to a learner utilizing a range of strategies. Some strategies are frequently used for the purpose of showing understanding, such as repeating (i.e., picking up the key words in a learner’s utterances), restating (i.e., bouncing back a learner’s ideas by reformulating their phrases), summarizing (i.e., abstracting main points), and empathizing (i.e., responding to a learner by identifying with their emotions). Other strategies focus more on helping a learner to expand their perspectives, such as linking (i.e., connecting details to bigger pictures) and asking powerful questions (i.e., asking questions that stimulate a learner’s reflective process; see Kato & Mynard, 2016, and Mozzon-McPherson & Tassinari, 2020, for a detail of advisor’s skills).

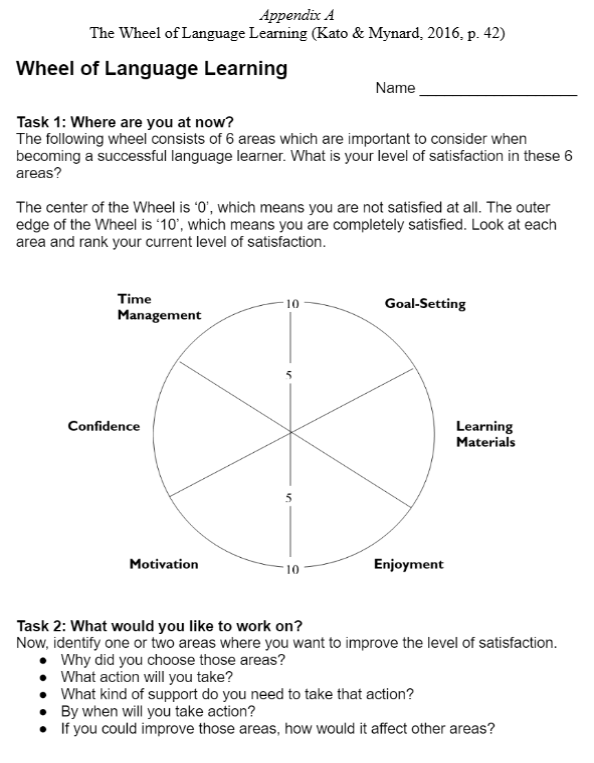

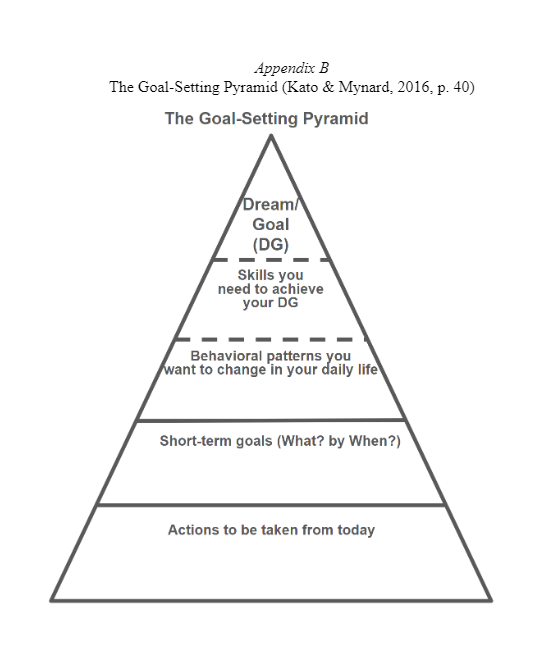

ALL may be further facilitated by the use of advising tools. They are defined as “ways to facilitate reflect processes” (Kato & Mynard, 2016, p. 29), which consequently foster learning. According to Mynard (2012), three types of advising tools are distinguished: cognitive, theoretical, and practical tools. Cognitive tools are designed to support a learner’s reflective process by gathering information about themselves as well as to plan future learning. These tools include self-evaluation or diagnostic sheets, the Wheel of Language Learning (Appendix A), and the Goal-Setting Pyramid (Appendix B). Some of these tools provide a learner with a means to express their thoughts with graphical representations instead of words, which reduces the cognitive burden for learners to engage in the reflective process. Theoretical tools refer to theories and knowledge, rather than physical artifacts, that an advisor makes use of in order to facilitate a learner’s learning. For example, an advisor may draw on their knowledge of language teaching or learning strategies to raise a learner’s awareness. Finally, practical tools involve practices and items that help to organize learning processes or advising sessions. A learner may keep records of their daily language learning tasks or use a journal to remember what they did each day. Such practices later help them evaluate their progress or identify possible issues.

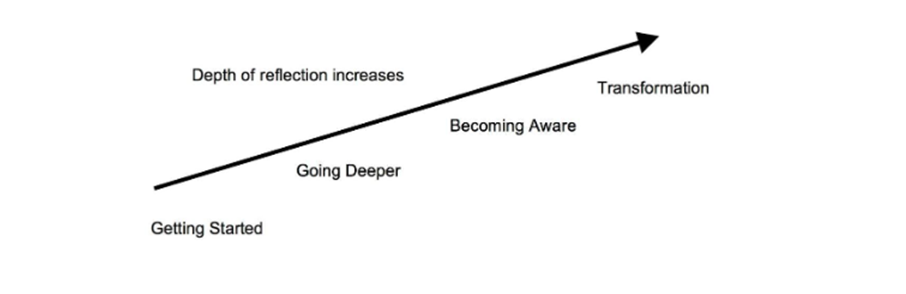

Development of a learner and an advisor in ALL. Learners who come to advising differ in terms of their readiness, requiring an advisor to carefully tailor scaffolding throughout the dialogue (Kato & Mynard, 2016). To effectively promote a learner’s reflection, an advisor needs to attend to the learner’s level of awareness of their learning. Kato and Mynard (2016) describe four stages based on literature and their experience with language learners. An advisor may take different approaches depending on where a learner is. Figure 1 illustrates the learning trajectory. As written in the figure, a deeper level of reflection is observed as a learner progresses through later stages.

Figure 1. The Learning Trajectory (Kato & Mynard, 2016, p. 13)

According to Kato and Mynard (2016), at the first stage of getting started, a learner has limited awareness of their learning process and tends to expect an advisor to provide solutions for them. For example, a learner may ask an advisor which resource to use or how much time to spend on a particular activity to achieve their goal. For such learners, an advisor would first ask questions to help clarify their situations, instead of telling what to do. The advisor then gradually leads the learner to possible ideas, from which they can choose to take action.

The second stage is going deeper, where a learner starts developing awareness and begins to describe more thoughts and feelings with some metalanguage (e.g., “I think…,” “I feel…,” “I realized…,” Kato & Mynard, 2016, p. 106). An advisor may hear utterances such as “[T]he action plan I made last week was good. But I find myself trying to escape from studying” (Kato & Mynard, 2016, p. 130) or “the to-do list scares me. Every time I see it, I feel overwhelmed…” (p. 130, emphasis in original). Different advising skills are utilized to deepen a learner’s reflection here (e.g., powerful questions, use of metaphors). With an advisor’s support, a learner starts noticing the reasons for their successes and struggles in language learning.

The third stage, becoming aware, involves a learner becoming able to describe their learning more clearly and start analyzing their situations critically. An advisor focuses on assisting a learner to see their situations from different points of view for grasping a better understanding of themselves. They may also find the next question to explore themselves. For instance, “I think the content is okay. But there is no audio file attached to this book and I find it difficult to use. Maybe I learn better by listening to it?” (Kato & Mynard, 2016, p. 156). An advisor then supports a learner to take action based on their realizations.

Finally, at the stage of transformation, a learner becomes largely aware of their learning process. They reflect not only analytically but also holistically, and they fully take control of their learning. With a learner at this stage, helping them realize their progress or achievements bears a greater importance. In some cases, a learner may attribute their success to their advisor. An advisor needs to help them take credit for what they have accomplished and get ready to eventually continue their language learning without an advisor.

Development does not happen only with learners. Advisors also develop as they gain experience and become more aware of their advising practice. Kato and Mynard (2016) describe an advisor’s development using the same trajectory, as illustrated in Figure 1. For an advisor, getting started means to start learning the basics of ALL and practicing advising. They may be occupied with thinking about what skills to employ in the session, and thus their focus may not be completely on the learner. Additionally, an advisor may face a gap between what they read or hear about ALL and actual practice. At going deeper, an advisor starts gaining experience of an entire advising process by having multiple sessions with each learner. Although an advisor at this stage becomes able to focus more on a learner while having a dialogue, they tend to use familiar skills repeatedly. When an advisor moves onto the next stage, becoming aware, they hold a certain amount of experience and become able to use a wider variety of advising skills. They are able to respond to a learner more flexibly. Finally, transformation is the stage where an advisor possesses a considerable amount of experience, being not only capable of adjusting how to approach a learner effectively but also of mentoring a new advisor.

Advisors’ Beliefs

Although beliefs are not necessarily a topic extensively studied in the field of ALL yet, they are inseparable from practice and may shape how we guide and support our students. As Yamamoto (2018) noted, “becoming a learning advisor does not merely entail skill acquisition; rather, the process of ‘becoming’ constantly challenges our beliefs, including our values, our educational philosophies and our own language learning experiences” (p. 112).

In fact, the field of ALL has documented some vignettes worth noting related to advisors’ beliefs. Howard et al. (2019), for example, reported on four advisors’ personal stories of their advising experiences. One of the advisors described a moment of powerful realization with regard to his belief as he learned about advising:

Advising has also changed my written dialogue with my students. E-mails I wrote before meeting advising were highly directive. […] I think I simply assumed that once we are there with a super solid action plan, the student could magically sort out the rest, and this “super solid” action plan would magically yield productive results. (pp. 340-341)

Yamamoto (2018) wrote an autobiographical reflection reflecting on her first year of becoming an advisor. Emphasizing the necessity of constant reflection on advising practice and beliefs, she shared a story that snapshots a critical transformation of her belief about advising:

Although I had substantial advising experience prior to my current career, the concept of advising seemed fairly different from what I believed as advising; my belief about advising was leading students to “successful” academic pathways. Thus, I had a strong belief that knowledge building was the most crucial aspect of professional development for advisors. On the other hand, what I often heard from experienced advisors was about taking an indirective approach to encourage learner reflection in advising session. I was stuck in a dilemma between two opposing ideas (p. 110)

As is the case in teaching, beliefs are not separable from advising practices, and research on this matter may help reveal more about the complex and dynamic nature of advising practices. With this background, I decided to conduct an exploratory case study of a novice advisor, myself, exploring advisors’ beliefs. The research question was: What types of beliefs are observed in advising reflection?

Methodology

Context

I work as an advisor at a private university near Tokyo in Japan. There are approximately 4,200 students majoring in foreign languages and global liberal arts. The university has a Self-Directed Learning Center (SALC), a facility designed to promote learner autonomy. ALL at my university takes place in the SALC, and this support is available for students of any major and year. There were 13 advisors in the year I wrote the reflection analyzed in this study.

It should be noted that how ALL is provided may differ from institution to institution. At my university, ALL is offered mainly in two different formats: reserved and non-reserved advising. Reserved advising sessions last 30 minutes. On the other hand, the duration of non-reserved advising sessions may vary. For these sessions, students come to a drop-in advising desk located in the SALC where an advisor is available for students to drop by without reservations. Students may have a rather short conversation for 10 minutes, or they may discuss deeper topics for 90 minutes at the longest. Advising sessions are typically one-on-one, one advisor and one student, but advisors may also occasionally have two students come together in one session.

Data collection and analysis

Self-study was applied as the research method. According to Sakui and Gaies (2003), similar to action research, self-study involves practitioners themselves as researchers, leading to a rich insight into their experience. While action research aims at problem solving, the purpose of self-study is for practitioners to reflect on their situation. It could incorporate problem solving, but it has a wider usage. Barcelos (2003) suggests “if one wants to investigate beliefs, one has to choose instruments that give access to participants’ own voices and interpretations” (p. 76). Self-study is one such research instrument that allows researchers to access participants’ own experiences.

The purpose of the study was to identify what types of beliefs can be observed in advising reflection. To answer the research question, data was collected from my own advising log written and saved digitally in a spreadsheet file for two academic semesters in my first year as an advisor. In this log, I recorded the dates of advising, session types (e.g., face-to-face or online, booked or casual advising), students’ names, their years and departments, purposes of advising, topics discussed during the sessions, and reflection on the sessions. The reflection was written following three guiding questions:

-

-

- What was positive about this session?

- If I could do the session over again, what would I do differently?

- What did I learn from the process?

-

These questions were used when I received an advising training provided by the university in the first month of working as an advisor, and I continued to use them for my own reflection for the first year of advising. There were 299 sessions recorded in the log. Two-hundred twenty-four sessions had a reflection entry. The remaining 75 did not have an entry because they were for a course-related purpose (e.g., a workshop for a credit-bearing self-directed learning course) or because I did not have time to compose an entry due to other tasks at work. The 224 reflection entries were examined in this study. They were numbered chronologically for the purpose of presenting the quotes from those entries in the following section (e.g., Log entry 1). Data analysis took place in my third year of being an advisor at the university.

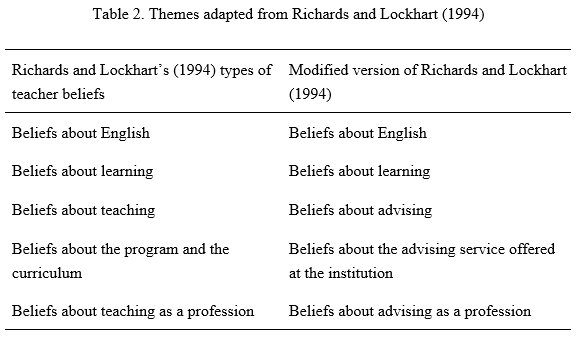

To analyze the data, I adapted Richards and Lockhart’s (1994) types of beliefs as a framework. I first modified some names of the types to fit the advising context (Table 2 contains a list of themes). The categories I started with in coding my logs are beliefs about English, beliefs about learning, beliefs about advising (adapted and reworded from beliefs about teaching), beliefs about the institutional advising program (adapted and reworded from beliefs about the program and the curriculum), and beliefs about advising as a profession (adapted and reworded from beliefs about teaching as a profession). I then analyzed each entry of my advising log according to the modified version of Richards and Lockhart. When an entry did not fit any of the types, I created a new category.

As for beliefs about advising, because there were a large number of entries classified under this category, I further conducted a thematic analysis on the entries, following the steps suggested by Braun and Clarke (2006). This process involved familiarizing myself with data, creating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining them, and finally reporting the findings.

Results and Discussions

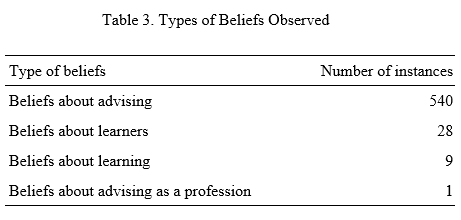

In this section, I present and discuss the results of analyzing the reflection entries. Table 3 shows the number of instances coded for each type of beliefs. Among the five types of beliefs I adapted from Richards and Lockhart (1994), three (beliefs about advising, learning, and advising as a profession) were observed. There were also entries about learners, which were coded and added as beliefs about learners to the list.

Beliefs about advising

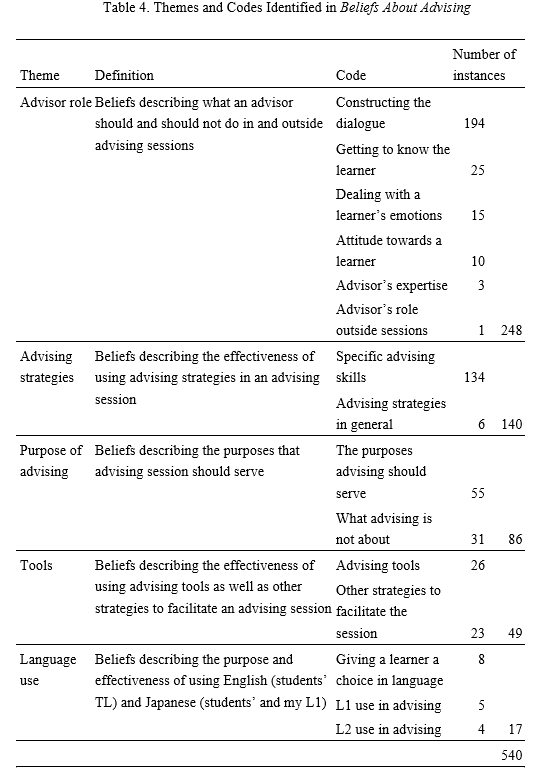

Among the types identified, beliefs about advising was the most frequent type of beliefs observed in my advising log (540 instances). I further analyzed them and identified the following themes: advisor role, advising strategies, purpose of advising, tools, and language use. Table 4 summarizes these themes and the number of instances for each.

The most frequent theme in this type of beliefs was advisor role. There were 248 log entries, accounting for 45.9% of beliefs about advising. These instances reflected my beliefs about what an advisor should do and not do. The log entries concerned such aspect of ALL as the way they should construct the dialogue (194 instances), the importance of getting to know the learner (25 instances), the way they should deal with a learner’s emotions (15 instances), the attitude they should have towards a learner in ALL (10 instances), the expertise they need to have (three instances), and the role they can play outside advising sessions (one instance).

Among the aspects of advisor role described above, my beliefs regarding what role an advisor should play in co-constructing a dialogue with a learner were prominent. In particular, my views on sharing experiences and providing input were being tested and confirmed through practice. While I was aware from my advisor training that learners could use some input from an advisor, I was initially hesitant to share my own experience as a learner:

[As something positive about the session,] [i]t was not me talking about myself, which was something I wanted to avoid … I am struggling with figuring out how I can structure a dialogue with a student who comes to listen to my experience. I tried to ask questions but it did not feel like I was doing my part as an advisor. (Log entry 56)

I would still share my experience when the learner asked, but there was uncertainty as to whether that was appropriate as an advisor. This confusion may indicate that I was at the getting-started stage, where an advisor starts experiencing gaps between theory and practice and begins building their understanding of what advising is, while the attention is often on the advisor themselves rather than their learner (Kato & Mynard, 2016). While experience sharing can be a useful technique, it is suggested that advisors keep it to a minimum and carefully choose where to utilize it in order to keep the focus of advising on learners (Kato & Mynard, 2016). At that time of the log entry, I was afraid that talking about myself might take away the focus of the session from the learner themselves. In fact, I had built a negative connotation to the act of providing input from my side. However, this view shifted when another advisor asked me to share my experience with his student. That student was going through a difficult time after failing a test to study abroad at an institution that she really wanted to go to. As I had a study abroad experience in another country, the advisor was hoping that hearing about it would broaden her perspective and encourage her to consider other options. I was asked to have an advising session with her, and she came to talk to me shortly after. After the session, I wrote:

[Another advisor] asked me to share my experience so that [student] can look for other opportunities. The process of advising is long-term and I feel like I did my job as part of her trajectory, at least along her long journey of language learning. I hope my sharing stories helps her broaden her perspective. (Log entry 138)

In the end, the session led me to acknowledging the positive role which sharing ideas and experiences can play in the long-term process of a learner’s learning. This change in perspective may show that I was getting to the going-deeper stage, the second stage of the advisor trajectory, where an advisor starts to recognize the whole process of advising beyond each session (Kato & Mynard, 2016).

Similarly, the necessity of providing input as a language learning expert, or of sometimes taking a more direct approach, was another aspect of ALL I confirmed through advising practice. In one entry, I wrote:

[The learner in the advising session] keeps sharing her thoughts but it didn’t seem to be feeding into something positive, so I decided to be a bit direct at times. […]

(To answer the guiding question “What did I learn from the process?”)

Sometimes I need to be a bit direct. […] I felt providing ideas as a language “expert” is part of the job. (Log entry 43)

As Mynard and Thornton (2012) suggested, an advisor faces a challenging task of deciding when is appropriate to provide input and when they should wait for their learner to explore and make a realization themselves. The particular log entry does not specify what input I had to provide the learner with, but it shows that I draw the conclusion that some situations require me to be direct and provide input as a qualified teacher who professionally studied language learning, rather than keep encouraging the learner to think by themselves.

The themes advising strategies and tools in the category of beliefs about advising reflected my perspectives on the effectiveness of those strategies and tools. Advising strategies refer to the specific active listening skills an advisor utilizes in a session with a learner such as repeating, restating, summarizing, and providing positive feedback (Kato & Mynard, 2016). There were 140 log entries coded as advising strategies (25.9% of the entries in beliefs about advising). Among them were comments regarding the effectiveness of specific advising strategies (134 instances) and the effectiveness of the strategies in general (6 instances). The entries in both showed that I generally had a positive view regarding the effectiveness of those strategies. For example, “I feel I can restate well when talking to her. … Restating is a powerful way to show that I’m listening and understanding her” (Log entry 184). Another entry reads, “[G]iving genuine positive feedback makes students happy and helps them gain confidence. It also brings about a positive flow of energy into the dialogue” (Log entry 49).

There were 49 instances coded for tools (9.1% of the entries in beliefs about advising). The theme tools includes both advising tools (26 instances; e.g., the Goal-Setting Pyramid; Appendix B) and other strategies that could facilitate an advising session (23 instances; e.g., note-taking during the session). In general, the log entries indicated my belief that using some visual material is effective to scaffold a reflective dialogue that can be challenging for learners, especially when conducted in their TL. I wrote in one entry: “Visual aids help a lot to give a structure to the dialogue for students who are at the getting-started stage” (Log entry 110). In that advising session, I used the Goal-Setting Pyramid with my student. His metalanguage was rather limited but he wanted to hold the session in English, his TL. From my point of view, it was helpful to use the advising tool because it visually presented a clear idea of what steps to follow in making an action plan with its triangular figure. I felt the session went smoothly, and the experience made me confirm the idea that I should make use of advising tools to guide a learner with limited linguistic resources.

With 86 instances, the theme purpose of advising accounted for 15.9% of beliefs about advising. These log entries reflected my idea regarding the purposes that I believed advising sessions should serve (55 instances) and what advising is not about (31 instances). For example, I strongly believed that one way advising sessions can be beneficial to a learner is by creating an action plan. Based on this view, by the end of each session, I would encourage a learner “to think about how she wants to study (make a plan) and invite her to another session at the end” (Log entry 23). I was also reminding myself of the idea that advising is not all about solving a learner’s issues, which guided my behavior in an advising session: “I didn’t go look for troubles/struggles from my end because now I’m consciously aware that advising is not all about ‘fixing problems'” (Log entry 21).

However, not every learner comes to an advising session seeking advising from the beginning (Davies et al., 2019). Some may not be aware of what advising is, while others may need more time before being ready to engage in a dialogue with an advisor about their learning. In my case, I often had students who came to an advising session to have a casual chat or do their speaking practice assigned by their teacher. From my experience of being an advisor and hearing and reading other advisors’ stories, this seems to be a common experience among advisors. Being a novice advisor, I was initially not certain of how to interpret the situation. I expected that a learner would usually come to advising sessions to talk about their learning and that the purpose of advising sessions would be, and should be, to support a learner with their learning. Thus, when a student came to my session to talk about casual topics, it triggered anxiety and frustration: “I was worried how the conversation would turn out this time because what we talk about had been often something not really related to language learning” (Log entry 69). This was another gap that I experienced between theory and practice, at the getting-started stage. A new perspective evolved as I encountered such a situation multiple times and discussed it with other advisors to hear their understanding of students. I started seeing that such casual conversations may not involve deep reflection per se but could actually be an important part of the advising process, “paving the ground for future advising” (Log entry 84), where I build rapport with a learner. In reality, students go to advising sessions voluntarily at my institution and there is no telling whether or not the casual conversation actually leads to advising in the future with such learners. Nevertheless, by holding this belief, I could somewhat relieve myself from the anxiety or frustration that I would otherwise feel when a dialogue did not go beyond a casual conversation. A log entry from a later session with another student shows I had a rather positive perspective: “She didn’t bring up any specific issues or problems this time. This session was a groundwork for future advising, if she needs it at some point” (Log entry 109). This change in my attitude may be another indication of transitioning from the getting-started stage to the going-deeper stage. It seems that I was learning to view the advising process more holistically rather than focusing only on each single session.

Finally, one more theme identified in beliefs about advising was language use (17 instances; 3.1% of beliefs about advising). The majority of the students who come to my advising sessions speak Japanese as their first language and learn English as their TL. I share the same background with those students. Because any language is welcomed in advising at my institution, I engage in advising either in Japanese, English, or mixed, depending on the student’s needs and preferences. The log entries coded under this theme reflected my beliefs about giving a learner an option to use either language (eight instances), English and Japanese use in advising (five and four instances, respectively). One aspect that I considered important about holding an advising session in English was that it can allow them to maximize their learning by creating an opportunity not only to reflect on their learning but also to practice the TL at the same time: “[the student] wanted to create opportunities to speak English outside the classroom and build confidence[.] I thought this would be a good chance for her to get a successful experience in talking in English with someone” (Log entry 199). This seems to resonate with Thornton’s (2012) finding that her advisor participants regarded student motivation as an advantage of TL advising sessions. On the other hand, through experiencing advising with the learners at my institution, I came to believe that the use of L1 is useful in certain situations. In one entry, I wrote “Again, using Japanese let me go deeper into the student’s thoughts. I feel L1 use is really helpful to find out what the real struggle is” (Log entry 14). For those whose metalanguage is limited in their L2, using L1 would, in my experience, expand the range of what they can express to their advisor during the session. Even for those who have higher proficiency in their L2 and are capable of using metalanguage to some extent, I believed using L1 could be beneficial because it would remove linguistic burdens posed by TL and allow them to focus on the reflective process, a challenging task for a learner by itself. For either type of learners, my belief was that using L1 is helpful to understand the learner and to promote reflection. Additionally, in another log entry, I wrote “We switched to Japanese in the middle of the session, and that was when she started to open up more…. Following her using Japanese for the rest of the session seemed to help build a rapport” (Log entry 10). I viewed another benefit of using Japanese to be building rapport, echoing some other advisors’ experiences documented in the literature (Thornton, 2012).

In my first year of advising, I was clarifying, confirming, and questioning my beliefs, while trying to understand advising through practice. I had received training at the beginning of the first year, but I was occasionally overwhelmed and confused in actual advising with students. At that time, while there were a few observations where I seemed to be transitioning to going deeper, the second stage of the advisor trajectory, I was mostly learning and filling gaps between theory and practice at the getting-started stage (Kato & Mynard, 2016). In other words, I was experiencing ruptures, or changes that require one to adjust or find a new balance (Zittoun, 2008), between the theory and the practice, or between the previous or parallel role as a teacher and the new role as an advisor (Tassinari, 2017).

The other types of beliefs observed

A total of 28 instances were coded under beliefs about learners, nine under beliefs about learning, and one under beliefs about advising as a profession. Compared to beliefs about advising (540 instances), these types of beliefs were much less prevalent.

The log entries in beliefs about learners showed my perspectives on learners. For example, after one session, I wrote in my log, “Perhaps learners sometimes feel nervous because they unconsciously believe they have to be perfect or they have to be really really good” (Log entry 83). In that session, I had a first-year student who was nervous about a class discussion she was supposed to have in her English class in a few days. As we explored her concerns, she seemed to be placing an unrealistic expectation to be able to carry on the discussion without any issues. In the session, I shifted her focus on not facing any difficulties to coming up with strategies to overcome expected challenges in a class discussion. I had had similar students before, and observing such students led me to the perspective that one of the causes of a learner’s anxiety is their holding unrealistic expectations.

The third type of beliefs identified, beliefs about learning, reflected my beliefs about language learning, concerning such aspects as language learning resources, strategies, exams, grammar, vocabulary, and evaluation. As a learning advisor has expertise in language learning, there occasionally emerges gaps between their and learners’ ideas. The example in the following shows a case where there is a discrepancy between a learner and myself in choosing an appropriate resource for language learning: “When he said he wants to use his word book to practice pronunciation. I was talking to myself saying ‘hmm he would probably benefit from using other resources like youtube videos.’” (Log entry 73). In this session, the student chose to use a word book while I was considering auditory resources and contextualized use of language. My decision as an advisor at that time was to ask how he believed his word book would be useful and not immediately suggest alternative options. However, if a learner struggles with their learning because of the way they engage in learning and remain unaware of the cause of the struggle, then I would need to take a more direct approach, choosing certain language learning resources to suggest. In such situations, similar to how teachers’ beliefs may shape the way they teach (Barcelos, 2016), advisors’ beliefs about what can help a learner to learn successfully (e.g., which resource is effective) would guide their decision-making in advising, which in turn may have an impact on a learner.

Finally, there was one instance coded under beliefs about advising as a profession. Although recent years have seen its growth as a field, ALL, is still considered innovative, rather than mainstream in Japanese educational settings (Mynard, 2019). The entry reflected such a wider context surrounding this profession: “I’m lucky to be able to work as an advisor, but this makes me worried thinking about what I’d do after” (Log entry 155). When I started as an advisor, as much as I believed in the important role advising can play in learners’ growth in language learning, my impression was that only a handful of universities in Japan implemented advising. I was uncertain about how ALL as a field could spread to other institutions in the future, and such a perspective led to a concern within myself.

Engaging in continuing reflective practice for professional development is recommended for learning advisors in order to avoid stagnation, where they repeatedly take similar approaches and do not challenge themselves with other advising styles (Kato, 2012). While the three types of beliefs were not as prevalent as beliefs about advising, they did seem to shape my advising practice and my view on ALL. Along with their beliefs about advising itself, an advisor may benefit from periodically re-visiting and examining their own beliefs or assumptions about learners, language learning, and advising, as well as how such beliefs impact their advising practice.

Conclusion

The purpose of the present study was to examine my own beliefs as a novice advisor in ALL, as observed in my reflective log entries. The findings suggested that an advisor may hold beliefs concerning various aspects of advising practice and language learning. Beliefs about advising accounted for the majority of the beliefs identified in this study, while beliefs about learners, language learning, and advising as a profession were also observed to a lesser degree. It was also suggested that those beliefs that a novice advisor may hold are not necessarily static but rather in process of being confirmed, questioned, or challenged over time.

There are several limitations that I should address concerning the findings of the study. I would like to note that the data was solely obtained from reflection log entries of one advisor, my own. Thus, the findings would not be comprehensive or generalizable to other advisors. Further studies that explore beliefs of other advisors, both novice and experienced, would be necessary to shed more light on advisors’ beliefs. Additionally, I relied on my own interpretation as I analyzed the data. While access to a participant’s own experience is an advantage of self-study (Sakui & Gaies, 2003), it is essentially subjective and limited to their own worldview. Finally, the focus of the study was to identify the types of beliefs observed in my reflection log entries. There remains a scope for future research to systematically investigate how such beliefs may evolve over time. Nevertheless, the study illustrated a snapshot of advisors’ beliefs that may play a role in ALL. The area of advisors’ beliefs offers a range of avenues to explore in the future, including the ones described above, and further research will contribute to accumulating knowledge of this evolving field.

Notes on the contributor

Haruka Ubukata is a Learning Advisor at the Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS). She has completed the Learning Advisor Education Program at the Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education (RILAE). She holds an MSEd in TESOL from Temple University Japan Campus.

References

Barcelos, A. (2003) Researching beliefs about SLA: A critical review. In P. Kalaja & A. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New research approaches (pp. 7–33). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Barcelos, A. (2016). Student teachers’ beliefs and motivation, and the shaping of their professional identities. In A. Barcelos (Ed.), Beliefs, agency and identity in foreign language learning and teaching (pp. 71–96). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137425959_5

Borg, M. (2001). Teachers’ beliefs. ELT Journal, 55(2), 186–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.2.186

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Buehl, M. M., & Beck, J. S. (2014) The Relationship Between Teachers’ Beliefs and Teachers’ Practices. In H. Fives, & M. G. Gill (Eds.), International Handbook of Research on Teachers’ Beliefs (pp. 66–84).

Carson, L., & Mynard, J. (2012). Introduction. In L. Carson, & J. Mynard (Eds.), Advising in Language Learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 3–25). Routledge.

Castro, E. (2019). Motivational dynamics in language advising sessions: A case study. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 10(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.37237/100102

Clark, C. M., & Peterson, P. L. (1986). Teachers’ Thought Processes. In: M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 255-296). Macmillan.

Davies, H., Stevenson, R., & Wongsarnpigoon, I. (2019). Shifting roles in continuous advising sessions. Relay Journal, 2(1), 69–72. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020110

Ferguson, L. E., & Lunn, J. (2021). Teacher beliefs and epistemologies. In S. C. Faircloth (Ed.), Oxford bibliographies in education. https://doi.org/10.1093/OBO/9780199756810-0276

Fives, H., Barnes, N., Chiavola, C., SaizdeLaMora, K., Oliveros, E., & Mabrouk-Hattab, S. (2019). Reviews of teachers’ beliefs. In S. C. Faircloth (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of education.https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.781

Gabillon, Z. (2012). Revisiting foreign language teacher beliefs. Frontiers of language and teaching, 3, 190-203.

Hampton, S. (1994). Teacher change: Overthrowing the myth of one teacher, one classroom. In T. Shanahan (Ed.), Teachers thinking, teachers knowing. NCRE. (pp. 122–140).

Howard, S. L., Güven-Yalçın, G., Karaaslan, H., Atcan Altan, N., & Esen, M. (2019). Transformative self-discovery: Reflections on the transformative journey of becoming an advisor. Relay Journal, 2(2) 323–332. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020208

Kalaja, P., Barcelos, A. M. F., Aro, M., & Ruohotie-Lyhty, M. (2015). Beliefs, agency and identity in foreign language learning and teaching. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137425959

Kalaja, P., Barcelos, A., Aro, M., & Ruohotie-Lyhty, M. (2016). Key issues relevant to the studies to be reported: Beliefs, agency and identity. In P. Kalaja, A. Barcelos, M. Aro, & M. Ruohotie-Lyhty (Eds.), Beliefs, agency and identity in foreign language learning and teaching (pp. 8–24). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137425959

Kato, S. (2012). Professional development for learning advisors: Facilitating the intentional reflective dialogue. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(1), 74–92. https://doi.org/10.37237/030106

Kato, S. (2022). Establishing high-quality relationships through a mentoring programme: Relationships motivation theory. In J. Mynard & S. J. Shelton-Strong (Eds.), Autonomy support beyond the language learning classroom: A self-determination theory perspective (pp. 164–182). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788929059-012

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

Mozzon-McPherson, M., & Tassinari, M. G. (2020). From language teachers to language learning advisors: A journey map. Philologia Hispalensis, 1(34), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.12795/ph.2020.v34.i01.07

Mynard, J. (2012). A suggested model for advising in language learning. In In L. Carson & J Mynard (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 26–40). Routledge.

Mynard, J. (2019). Self-access learning and advising: promoting language learner autonomy beyond the classroom. In H. Reinders, S. Ryan, & S. Nakamura (Eds.), Innovation in language teaching and learning: The case of Japan (pp. 185–209). Palgrave Macmillan Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12567-7_10

Mynard, J. (2022). Perspectives on self-access in Japan based on a typology and a thematic analysis of the literature. JASAL Journal, 3(2), 4–21.

Mynard, J., & Thornton, K. (2012). The degree of directiveness in written advising: A preliminary investigation. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.37237/030104

Richards, J. C., Gallo, P. G., & Renandya, W. A. (2001). Exploring teachers’ beliefs and the processes of change. PAC Journal, 1(1), 41-58.

Richards, J. C., & Lockhart, C. (1994). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667169

Sakui, K., & Gaies, S. J. (2003). A case study: Beliefs and metaphors of a Japanese teacher of English. In P. Kalaja & A. M. F. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New research approaches (pp. 153–170). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-4751-0_7

Sampson, R. (2020). Trying on a new hat: From teacher to advisor. Relay Journal, 3(2), 250–256. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/030211

Shelton-Strong, S. J. (2022a). Advising in language learning and the support of learners’ basic psychological needs: A self-determination theory perspective. Language Teaching Research, 26(5), 963–985. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820912355

Shelton-Strong, S. J. (2022b). Sustaining language learner well-being and flourishing: A mixed-methods study exploring advising in language learning and basic psychological need support. Psychology of Language and Communication, 26(1), 414–499. https://doi.org/10.2478/plc-2022-0020

Stickler, U. (2001) Using counselling skills for advising. In M. Mozzon-McPherson, & R. Vismans. (Eds.), Beyond language teaching towards language advising. (pp. 40–52). CILT.

Tassinari, M. G. (2016). Emotions and feelings in language advising discourse. In C. Gkonou, D. Tatzl & S. Mercer (Eds.), New directions in language learning psychology (pp. 71–96). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-23491-5

Tassinari, M. G. (2017). How language advisors perceive themselves: Exploring a new role through narratives. In C. Nicolaides & W. Magno e Silva (Eds.), Innovations and challenges in applied linguistics and learner autonomy (pp. 305–336). Pontes.

Tassinari, M. G., & Ciekanski, M. (2013). Accessing the self in self-access learning: Emotions and feelings in language advising. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(4), 262–280.: https://sisaljournal.org/archives/dec13/tassinari ciekanski/

Thornton, K. (2012). Target language or L1: Advisor’s perceptions on the role of language in a learning advisory session. In L. Carson & J Mynard (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 65–86). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833040

Yamamoto, K. (2018). The journey of ‘becoming’ a learning advisor: A reflection on my first-year experience. Relay Journal, 1(1), 108–112. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010110

Zittoun, T. (2008). Learning through transitions: The role of institutions. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 23(2), 165-181.

Appendices

Dear Haruka,

Thank you for your self-study on a learning advisor’s beliefs on advising. It was a pleasure to read and brought back memories of our shared office, where you worked late composing your advising logs.

As you noted in your paper, I also believe that advisor beliefs are constantly constructed as learning advisors encounter new students with diverse purposes on a daily basis. This makes each advising session unique. I especially resonated with one of your entries where you hesitated to share your own experiences. I felt the same way during my first year as an LA. I had a strong belief in two key advising principles: “it’s not about you” and “leave your assumptions at the door,” which initially made me hesitant to share my experiences with learners. The many similarities between my learners and myself—such as being someone who learned English as a foreign language and went through the Japanese education system—further amplified my hesitations compared to other foreign LAs.

Later, I began sharing my experiences with my regular advisees after we had built sufficient rapport. Just as rapport building is crucial for learners, it is equally important for an LA when deciding to share own experiences.

I think advisor beliefs are a topic we could endlessly discuss, and your paper will certainly encourage more LAs to share their own perspectives and beliefs about their roles as advisors.

I have two questions for you:

1. It seems that you composed your logs in English. Why did you choose your TL for the entries? In your paper, you mentioned that using the TL helped learners deepen their reflections. How about you?

2. If you could give advice to your first-year self about advising, what would you tell?

I look forward to hearing from you.

All the best,

Yuri

Dear Yuri,

Thank you so much for such encouraging comments!

It brought me an aha-moment when you mentioned that building rapport is crucial not only for learners but also for advisors. It indeed encourages us to believe in ourselves., unlocking more potential to support our learners.

Thank you for those questions, too! They certainly made me reflect further on my advising in these past years.

As for the language I used for keeping record, in retrospect, I believe I was writing in English partially because English was a “default”, shared language at my institution. However, I actually started making a more conscious choice recently regarding the language used to keep record. I now use English for sessions held in English and Japanese for ones done in Japanese. When a learner and I used both languages, I mix languages. I started taking this approach because I wanted to remember which language each student felt more comfortable with in each session and also because I wanted to write down the learners’ words in the way they used in the session. Your question brought me a new perspective on my own use of Japanese and English, and I would like to spend some time to think about this. As I am exposed to the field predominantly in English (e.g., taking advising courses, reading literature, discussing with colleagues about advising practices), I might have more language to express thoughts in English.

If I could give advice to my first-year self, I would first tell her that I am proud of her making an earnest effort as an advisor! While I myself see a long (and yet exciting) way to explore as an advisor, it is her that brough me where I am. I would like to thank her and encourage her to keep going!

Thank you again for sharing your thoughts on my article!

Haruka

Dear Haruka,

I had the pleasure of reading your manuscript. First, I want to say how impressed I am with your dedication to this self-study. Collecting and analyzing 224 reflection log entries is a remarkable achievement that reflects your commitment to professional development! This extensive dataset enriches your findings and provides a solid foundation for your analysis, offering readers a vivid view of a novice advisor’s journey.

Your use of Richards & Lockhart’s (1994) framework, modified to fit the context of Advising in Language Learning (ALL), is a great idea. By adapting their classification of teachers’ beliefs to an advising context, you provide a structured lens to examine beliefs about advising, learners, learning, and the profession. Furthermore, your thematic analysis of the data adds depth to the study, particularly in identifying key themes within the category of beliefs about advising, such as the advisor’s role, advising strategies, and language use.

One of the strengths of your paper is how clearly it shows your growth as an advisor over the course of the year. A particularly compelling example is your shift in belief about sharing personal experiences. Initially, you hesitated and struggled to share your own learning experiences, fearing that doing so might take the focus away from the learner. However, the case where your colleague encouraged you to share your study-abroad experience with a learner navigating a difficult emotional situation provided a turning point. You reflected on the long-term role of advising and wrote:

“The process of advising is long-term, and I feel like I did my job as part of her trajectory, at least along her long journey of language learning. I hope my sharing stories helps her broaden her perspective.” (Log entry 138)

This is a wonderful illustration of how your understanding of the advising process became more holistic and how you began to see the value of sharing personal experiences when appropriate. It is an excellent example of how a novice advisor can adapt theoretical ideas to meet the needs of learners in practice. Including such examples makes your paper not only insightful but also highly practical for future novice advisors who might face similar uncertainties.

I also appreciated how your study highlights the importance of reflection in bridging the gap between theory and practice. It would be fascinating to hear more about how this year-long process of reflection shaped your growth. For instance, how do you imagine your advising practice might look today if you had not engaged in this self-reflective journey?

Another aspect that intrigued me was how this reflective log approach could be adapted for training new advisors. If you were to implement this as part of an advisor education program, how might you structure it? Are there aspects of the data collection process or log format you would modify to make it even more effective for novices?

Finally, while your study focuses on beliefs, I wonder how these beliefs translate into actual advising practices. If you were to delve deeper into the relationship between beliefs and advising outcomes, what methods might you consider? For example, would you explore learner feedback or observe advising sessions to see how beliefs influence practice?

Overall, I found your paper to be a valuable contribution to the field of ALL. It provides both theoretical insights and practical examples that will undoubtedly resonate with advisors at all stages of their careers. Thank you for sharing this work, and please do not hesitate to reach out if you would like to discuss any of these points further.

Warm regards,

Satoko

Dear Satoko,

Thank you for reading my article and sharing such kind, encouraging comments with me. I feel very grateful and I hope this article can provide ideas, insights, and courage for other advisors to go on with their advising journey.

The process of reflecting on my advising was helpful in several ways. First, especially when I had advising sessions one after another, writing a log physically and mentally helped me to “take a deep breathe”. When my mind got full of thoughts and emotions after a session, it was helpful to write it down to take some load off before going to another session. Second, by putting thoughts into words, it clarified what was making me feel in a certain way. While having a dialogue with another advisor is certainly effective in this sense, having a log was another, highly practical and accessible way for me. In addition, now I realize that the process of looking back at my reflection entries through the analysis for this present study itself had a great benefit. When I looked back at my own reflections after two years or so, I realized where I have developed as an advisor, which brings me a sense of achievement and more passion to continue to develop professionally. Without those reflections from my first year, I could not have had that.

To adapt the reflective log approach to implement in advisor training, the first thing that came to my mind was its demand for time. Reflecting on each session requires a certain amount of time. Doing so after every single session may not be realistic for some. It might be necessary to adjust the frequency of writing a log depending on the situation. Also, other reflective questions could be employed to trigger reflection on specific targets. Providing a list of those questions and giving each trainee a choice might generate more meaningful reflection. Finally, I believe it is important that we come back to our own reflection after a while (e.g., one semester, a year) as it could let us see a more holistic view of our own development.

I would be very interested in exploring how beliefs may translate into action as you suggested. Perhaps recording and observing advising sessions from different points of time (e.g., at the beginning, middle, and end of a year) might lead to interesting insights. I am excited to learn more about advising (and myself) in the future!

Thank you again for your insightful comments. I would like to continue to make an effort to develop as an advisor and contribute more in this fascinating field of advising!

Haruka