Eduardo Castro, Kanda University of International Studies

Ella Lee, Kanda University of International Studies

Castro, E. & Lee, E. (2024). Promoting Learner Well-Being in a Self-Access Learning Center. Relay Journal, 7(2), 98-108. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/070204

[Download paginated PDF version]

Abstract

This article describes our institutional effort to explicitly raise learner awareness of well-being through a week-long program of activities and resources in the Self-Access Learning Centre (SALC) at Kanda University International Studies (KUIS), Japan. The initiatives encompassed interactive posters and resource recommendations, along with engaging conversations, nature-oriented activities, utilization of the Maker Conversation, and interactive workshops focused on managing language anxiety, cultivating mindfulness, nurturing positive emotions, and regulating mood through music. Our report centers on our experiences, considering the challenges and the opportunities of how self-access centers can contribute to the promotion of learner well-being.

Keywords: learner well-being, self-access learning centers, learner awareness.

Well-being has received increased attention in language education over the last decade. It has been recognized as a significant goal for language education in the 21st century, relevant to both individuals (e.g., teachers and learners) and institutions (e.g., schools and universities) (Mercer et al., 2018). Despite this growing attention, well-being remains a complex construct defined in different ways according to the field. Sulis et al. (2023) describe two viewpoints to consider well-being: hedonic and eudaimonic. The former views well-being as overall life satisfaction and happiness which relies on individuals’ perceptions of the balance between positive and negative emotions. In contrast, the latter focuses on positive functioning, authenticity, and self-actualization, emphasizing individuals’ ability to lead meaningful lives. According to the Sulis et al., Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model integrates both hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives, regarding well-being as emerging from the combination of the following dimensions: positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and achievement.

Taking an ecological perspective on language learning, Mercer (2021) defines well-being as “the dynamic sense of meaning and life satisfaction emerging from a person’s subjective personal relationships with the affordances within their social ecologies” (p. 16). Mercer not only considers well-being as an individual experience but also as an institutional responsibility, stating that “well-being is not only subjective and individual, but it is also objective and social” (p. 16). This suggests that well-being is best promoted systemically by various agents in educational institutions, including learners, teachers, and staff. Currently, there is a growing body of research focusing on teacher well-being (MacIntyre et al., 2019; Mercer, 2023). However, the discussion of how to promote well-being in relation to language learning and linguistic development in a self-access learning context is still underexplored. In this regard, this article outlines our institutional efforts to explicitly raise learners’ awareness of well-being through a week-long program of activities and resources at the Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) in Japan. This article focuses on our experiences, addressing the challenges and opportunities we encountered, and explores different ways self-access centers can contribute to the promotion of learner well-being.

The Self-Access Learning Center at KUIS

A SALC is a facility dedicated to fostering language development, encouraging learner autonomy, and cultivating self-directed learning skills (Mynard, 2022). As a dynamic learning environment, a SALC provides diverse affordances for language learning, including advising support, interest-based learning communities, events, workshops, and linguistic assistance from both teachers and peers (Magno e Silva, 2017, 2018). Recent insights into SALCs emphasize that they are not just spaces to support learners’ development of linguistic skills. They also play a crucial role in raising awareness of the emotional aspects of learning as well as in considering learners’ basic psychological needs and well-being (Mynard & Shelton-Strong, 2022). As learner-defined spaces, SALCs can be conceptualized as a place “to thrive and grow as human beings” (Mynard, 2022, p. 225). This suggests that a SALC can explicitly address and fully incorporate the PERMA model in relation to language learning into its daily practices.

The SALC is an important affordance for students at KUIS and stands as an inclusive hub for language development, providing opportunities for social interaction and connection among students. Embedded within our mission statement is a commitment to fostering an environment conducive to holistic language learning and cultural appreciation (Mynard et al., 2022), as described in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1

The SALC mission statement (Mynard et al., 2022, p. 33)

The Well-Being Awareness Week

The Well-Being Awareness Week emerged as a response to the increasing number of students seeking out support for mental health issues in one-to-one meetings with learning advisors at the SALC. As this goes beyond advisors’ competencies, we wondered how we could raise learners’ awareness of mental health while promoting learner well-being. We thought that a whole-SALC event would be an appropriate answer to this question, as this would be an opportunity to collaborate with different agents of the ecology of the SALC (e.g., advisors, teachers, and SALC staff) as well as reach out to a greater number of students in the center. This event represents our first attempt to explicitly address these matters. The program included interactive posters and resource recommendations, conversations with advisors and teachers, nature-oriented activities, utilization of the Maker Conversation and English Lounge, as well as interactive workshops focused on managing language anxiety, cultivating mindfulness, nurturing positive emotions, and regulating mood through music. In the following subsections, we present the activities and initiatives and describe how they addressed learner well-being.

Opportunities for Reflection on Well-Being

Advising in language learning is “an intentional dialogue whose aim is for the learner to be able to reflect deeply, make connections, and take responsibility for his or her language learning” (Kato & Mynard, 2016, p. 2). At the SALC in KUIS, students can either schedule appointments in advance with learning advisors or meet with them at their convenience at the Drop-in Desk, without the need for an appointment. To facilitate these impromptu conversations during the Well-Being Awareness Week, the team of advisors collaboratively prepared a set of reflective questions focused on confidence, self-care strategies to prevent learning burnout, reflection on achievements, and personal growth. In line with our aim to foster learner autonomy, students could choose which questions they felt more comfortable to address. Example questions include:

-

- When do you feel the most confident?

- What’s a time in university when you felt you were at your best?

- What went well this week for you?

- What do you do that makes you feel proud of yourself?

- What do you usually say to yourself when you need some extra strength to do something well? How does it help?

- How are you taking care of yourself this week?

- How have you helped others this week?

Students at the SALC have the opportunity to improve their conversational skills by joining the English Lounge (Mynard et al., 2020), an informal setting, where students can participate in conversations. They are welcomed by teachers who bring games and conversation topics to facilitate discussions. During the Well-being Awareness Week, a different set of questions was provided for teachers and students to use at their convenience, covering topics such as confidence, self-understanding, gratitude, and personal growth. Examples of questions include:

-

- How confident are you?

- What do you usually say to yourself when you need some extra strength to do something well? How does it help?

- What is your favorite spot on campus, and why do you like it?

Moreover, the event included a series of workshops offering practical ideas on understanding and managing language anxiety, practicing mindfulness, fostering positive emotions in language learning, and regulating mood through music. These 40-minute lunchtime workshops were led voluntarily by learning advisors and teachers. It is important to mention that some workshops had fewer participants than expected. However, as the event organizers, we believe the effort was worthwhile, even if only one student benefited. The teachers and learning advisors volunteered their time to share well-being insights with attendees, creating valuable experiences that may resonate beyond the workshop. In the future, it may be worth exploring other workshop formats, such as casual, open-space sessions like poster presentations, to potentially attract a larger number of students. This approach could provide a more engaging, informal environment, encouraging students to ask questions and share experiences more freely.

Creative Self-Expression Activities & Resource Recommendations

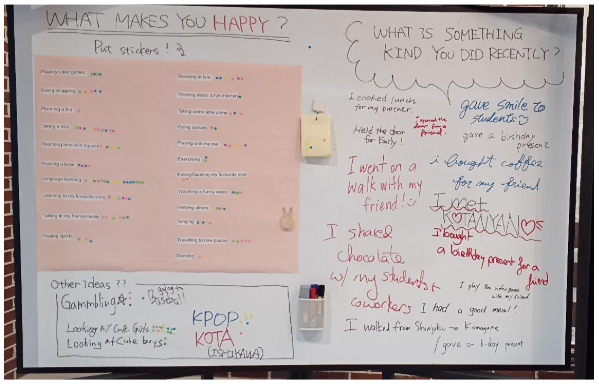

At the SALC, interactive whiteboards and posters are frequently used to promote engagement, providing students with a public yet informal platform to share their thoughts, ideas, and feelings anonymously. The whiteboards are placed throughout the center and invite students to contribute through writing or drawing, creating a collaborative space for self-expression. During the Well-Being Awareness Week, students were encouraged to share their joyful experiences and acts of kindness (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Interactive whiteboard on happiness and kindness

In addition, resource recommendations are a key part of the SALC culture. There is a designated area in the center where learning advisors regularly display resources tailored to different themes. For the event, we curated resources such as movies and books, related to mental health, emotions, resilience, positive relationships, and friendship, and displayed them in that area.

The Maker Conversation is designed as a space where students can enjoy English conversation while engaging in hands-on creative activities such as design, technology, and arts and crafts (Taube-Shibata & Lorentzen, 2023). For the Well-being Awareness Week, the teachers in charge adapted the space to focus on self-exploration projects that promoted emotional reflection. Activities like coloring mandalas or creating artwork related to gratitude provided students with opportunities to raise their self-awareness. The outcomes of these conversations sparked further discussions within the SALC. For example, the collaboratively created mandala was displayed in the center (Figure 3), allowing students who did not participate in the activity to join the ongoing discussion on happiness.

Figure 3

Mandala created in the Maker Conversation displayed in the SALC

Community Building and Social Engagement Activities

In addition to self-reflection and self-expression initiatives, the Well-Being Awareness Week also considered opportunities for community engagement. For example, “Walk and Talk” sessions were organized a couple of times throughout the week. In this activity, learning advisors took walks around campus with students, discussing their favorite spots on campus. It provided students with a refreshing break from their assignments by taking the learning experience outside of the walls of the SALC.

Another activity promoting engagement was the yoga session combined with mindfulness. Initially planned as one of the workshops described in the previous section, it took on a life of its own because it happened in a different location outside of the SALC. Led by two teachers, the session brought together students, teachers, and staff at a tatami-floor room to experience mindfulness and relaxation through movement.

Learning Communities (LCs) are a core component of the SALC, as students can participate in groups based on their shared interests or goals. These communities are designed to foster a sense of belonging while supporting language learning through collaborative activities (Watkins, 2022). They are student-led and meet once a week at times that suit members’ schedules. Different LCs incorporated well-being into their activities during the event week. For example, the Journaling LC reflected on how they could promote a positive change in their surrounding community, the Portuguese LC practiced expressing positive emotions and keeping gratitude journals in Portuguese, and the Korean LC exchanged motivational messages using song lyrics.

On the last day of the event, we organized a movie session on the importance of embracing diverse emotions. In the SALC, movie sessions are occasionally offered as a way for students to relax and engage with learning languages and cultures in a fun, informal setting. For this event, we provided a comfortable space with snacks, and students were able to relax and enjoy the movie in a friendly atmosphere. Although we did not allocate time for a discussion afterward, we believe it would be valuable to consider adding it to future events to encourage reflection on emotional well-being. Using the movie as a starting point for reflecting on well-being could be highly beneficial. Despite this, the movie session attracted a significant number of students and served as a positive way to conclude the Well-Being Awareness Week activities.

Final Considerations and Implications for Practice

The Well-Being Awareness Week marked our first attempt to explicitly promote learner well-being in the SALC, and we successfully engaged over 80 attendees in just one week, including both students and staff. While the occasion primarily focused on learner well-being, the activities also resonated with teachers, advisors, and administrative staff, who actively participated in various events, particularly the workshops and the yoga session. Notably, the yoga session had attendance from employees across different departments who expressed enthusiasm for additional sessions specifically for university staff. This positive feedback prompted collaboration with the university’s sports center to explore and promote similar physical well-being initiatives. Another collaboration opportunity included the university’s medical center, whose staff volunteered to lead informational sessions on mental health in a future iteration of the event. Finally, as a direct result of the event, pamphlets and posters promoting the university’s counseling services have become permanent in the SALC.

In future editions of the event, it would be helpful to clarify the definition of well-being and provide a rationale for organizing it for students, teachers, and staff. Individuals have different beliefs about well-being and may feel uncertain about how to promote it in an educational context, such as a SALC. In addition, some people may not fully understand the relevance or necessity of a well-being event from an institutional perspective, especially if the attendance is low. Therefore, clarifying the scope of a well-being event for all stakeholders could encourage greater engagement and participation. Furthermore, while the goal is to reach as broad an audience as possible, it is important to recognize that the event can still be successful even with a small number of attendees. To foster a well-being culture within an institution, it is acceptable to start with a small group of participants who, after benefiting from the event, are likely to inspire others to engage in well-being-related activities, as exemplified by the mandala in Figure 3.

Although this article focuses on our experiences in a learning environment outside the classroom, the practical ideas described in this initiative can be implemented by language teachers and practitioners interested in fostering a culture of well-being within their institutions, even in the absence of a SALC. For instance, interactive boards, pamphlets with counseling information, and posters encouraging individuals to seek professional help, if needed, could be easily displayed in contexts such as classrooms, schools, and universities. In addition, positive resonance moments can be created in the classroom through the inclusion of mindful meditation at the beginning of the class (Barcelos, 2013). Finally, teaching students to understand and articulate their emotions, and helping them reflect on how these emotions influence their language learning experiences, can be introduced through warm-up questions. Alternatively, this could be designed as a standalone course integrating activities such as diary writing and sharing, creation of portfolio showcasing their personal growth, or projects displaying their creativity (Castro & Shelton-Strong, 2024).

The Well-Being Awareness Week has been added to the SALC calendar. In our capacity as learning advisors and event organizers, it was highly rewarding to see many participants engage in the activities in various ways. As described throughout this paper, all the activities and initiatives during the event were led by different members of the SALC community. These included students leading the learning communities, staff handling event advertising and logistics (e.g., reserving rooms, providing snacks), teachers facilitating conversations, and learning advisors offering resource recommendations, supporting reflective dialogue, and suggesting questions on well-being, among other contributions. The engagement of all parties involved, along with the diverse positive feedback received, highlights the ripple effect both within and beyond the SALC, suggesting that it takes a village to promote learner well-being in language education.

Notes on the contributors

Eduardo Castro is a learning advisor and lecturer in the Self-Access Learning Center at Kanda University of International Studies, Japan. He holds an MSc in Applied Linguistics from the Federal University of Viçosa, Brazil. His research interests include learner autonomy, advising in language learning, the psychology of language learning and teaching, with an emphasis on the motivational and emotional dimensions of language education.

Ella Lee is a learning advisor and lecturer in the Self-Access Learning Center at Kanda University of International Studies, Japan. She holds a master’s degree in Language Education from the International Christian University, Japan. Her research interests include learner autonomy, advising in language learning, and interest-based learning communities.

References

Barcelos, A. M. F. (2013). We teach who we are (becoming). PeerSpectives, 10, 2–6.

Castro, E., & Shelton-Strong, S. J. (2024). Exploring emotions in language learning: Learners’ self-awareness, personal growth, and transformation on a CLIL course. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688241267366

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

MacIntyre, P., Gregersen, T., & Mercer, S. (2019). Setting an agenda for positive psychology in SLA: Theory, practice, and research. The Modern Language Journal, 103(1), 262–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12544

Magno e Silva, W. (2017). The role of self-access centers in foreign language learners autonomization. In C. Nicolaides & W. Magno e Silva (Eds.), Innovations and challenges in applied linguistics and learner autonomy (pp. 183–207). Pontes.

Magno e Silva, W. (2018). Autonomous learning support base: Enhancing autonomy in a TEFL undergraduate program. In G. Murray & T. Lamb (Eds.), Space, place and autonomy in language learning (pp. 219–232). Routledge.

Mercer, S. (2021). An agenda for wellbeing in ELT: An ecological perspective. ELT Journal, 75(1), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccaa062

Mercer, S. (2023). The wellbeing of language teachers in the private sector: An ecological perspective. Language Teaching Research, 27(5), 1054–1077. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820973510

Mercer, S., MacIntyre, P., Gregersen, T., & Talbot, K. (2018). Positive language education: Combining positive education and language education. Theory and Practice of Second Language Acquisition, 4, 11–31.

Mynard, J. (2022). Reimagining the self-Access center as a place to thrive. In J. Mynard & S. Shelton-Strong (Eds.), Autonomy support beyond the language learning classroom: A self-determination theory perspective (pp. 224-241). Multilingual Matters.

Mynard, J., Ambinintsoa, D. V., Bennett, P. A., Castro, E., Curry, N., Davies, H., Imamura, Y., Kato, S., Shelton-Strong, S. J., Stevenson, R., Ubukata, H., Watkins, S., Wongsarnpigoon, I., & Yarwood, A. (2022). Reframing self-access: Reviewing the literature and updating a mission statement for a new era. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 13(1), 31–59. https://doi.org/10.37237/130103

Mynard, J., Burke, M., Hooper, D., Bethan, K., Lyon, P., Sampson, R., & Taw, P. (2020). Dynamics of a social language learning community: Beliefs, membership and identity. Multilingual Matters.

Mynard, J., & Shelton-Strong, S. J. (2022). Self-Determination Theory: A proposed framework for self-access language learning. Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning, 4(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.52598/jpll/4/1/5

Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Atria Books.

Sulis, G., Mairitsch, A., Babic, S., Mercer, S., & Resnik, P. (2023). ELT teachers’ agency for wellbeing. ELT Journal, 78(2), 198–206 https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccad050

Taube-Shibata, J., & Lorentzen, A. (2023). Maker conversation: Successes and challenges in a university SALC. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(2), 232–239. https://doi.org/10.37237/140207

Watkins, S. (2022). Creating social learning opportunities outside the classroom: how interest-based learning communities support learners’ basic psychological needs. In J. Mynard & S. Shelton-Strong (Eds.). Autonomy support beyond the language learning classroom (pp. 109–129). Multilingual Matters.

This article offers an important contribution to language education by highlighting learner well-being in self-access centers, an underexplored yet crucial area in the field. The authors’ initiative at Kanda University of International Studies demonstrates how thoughtfully designed activities—such as reflective dialogue, mindfulness workshops, and creative expression—can support students’ emotional, social, and academic growth. By fostering spaces for self-reflection, connection, and personal development, the Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) provides a meaningful example of how learner well-being can be integrated into language learning environments.

The authors’ ecological approach, which emphasizes collaboration among students, learning advisors, and staff, aligns very closely with social-emotional learning (SEL) principles that focus on self-awareness, emotional regulation, and positive social interaction. In fact, this article can easily be considered part of the SEL literature in our field – well done. The authors’ efforts underscore the potential for SALCs to be spaces where students improve their language skills, build resilience, and strengthen their sense of belonging. Future iterations of this initiative could perhaps benefit from student reflections or follow-up data to capture the lasting impacts on participants. Similarly, I recommend approaching future studies like this one through an SEL lens. Regardless, this article offers valuable insights and practical recommendations for promoting well-being, both in SALCs and more traditional learning environments. Congratulations to the authors for this very interesting work.

Dear Luis,

Thank you very much for taking the time to read the paper. We truly appreciate your feedback and suggestions regarding the inclusion of the SEL framework to promote students’ well-being in the SALC. Indeed, the framework aligns well with our aims and philosophy, and we will keep it in mind the next time we organise the event.

In addition, we agree that incorporating students’ reflections would enrich the paper, so this could be a valuable next step in future events.

Thank you again!

Eduardo and Ella