Jo Mynard1, 2, 3, Bethan Kushida1, 2, 3, Chris Arnott2, 3, Kodiak Atwood3, Phillip Bennett3, Eduardo Castro2, 3, Adam Garnica3, Michelle Jerrems3, Hao Jingxin3, Ella Lee3, Ewen MacDonald2, 3, Peter Macdonald3, Emily Marzin2, 3, Scott Shelton-Strong3, Robin Sneath3, Jamison Taube-Shibata2, 3, Haruka Ubukata3, Isra Wongsarnpigoon2,3, Allen Ying3

Mynard, J., Kushida, B., Amott, C., Atwood, K., Bennett, P., Castro, E., Garnica, A., Jerrems,

M., Jingxin, H., Lee, E., MacDonald, E., Macdonald, P., Marzin, E., Shelton-Strong, S., Sneath,

R., Taube-Shibata, J., Ubukata, H., Wongsampigoon, I., & Ying, A. (2025). Barriers and

motivations for using (or not using) English in a self-access learning center. Relay Journal,

8(1), 3-26. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/080102

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Notes on the authors

1. Project coordinator

2. Involved in writing this paper

3. Involved in project design, data collection and analysis

Abstract

This study investigates the factors influencing students’ language practices and attitudes toward using English in the Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) in a post-pandemic era. Drawing on self-determination theory (SDT) and one of its mini-theories, basic psychological needs (BPN) theory, the research explores how autonomy, relatedness, and competence shape students’ engagement with English in this social learning environment. A qualitative analysis of data collected through interviews with 141 SALC users revealed that while the environment is largely autonomy-supportive and many students value the opportunities to use English, many users lack agency or are satisfied with their relatively limited use of English in the SALC. The results highlight significant barriers that impede the use of English, including the perceived lack of competence, compounded by affective challenges such as feelings of anxiety. In addition, although participants felt a sense of relatedness and regularly interacted with a community of other students in the SALC, the established practice of using Japanese with this group hindered their use of English. The researchers also sought users’ views on the English-only policy on the second floor of the SALC. While the majority of students support the policy in principle, opinions varied on its enforcement, with most advocating for a supportive rather than strict approach. Based on these insights, the researchers recommend maintaining the current policy while enhancing interventions to promote English use, including targeted support systems, linguistic tools, and community-building strategies. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of how SALCs can better serve diverse learner needs and foster meaningful engagement with the target language.

Keywords: social learning spaces, English support, language practice, basic psychological needs, language policy

The purpose of this paper is to explore students’ language practices and views on using English in a designated area of a Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) in Japan. The findings provide insights into students’ motivations for English and how they engage with the SALC, helping the researchers understand their needs and refine the language policy to better support the KUIS community. Specifically, this study examines how various factors influence students’ use (or non-use) of English in the SALC and highlights key areas for intervention to enhance language learning opportunities.

Although similar research has previously been conducted in the same institution relatively recently (Asta & Mynard, 2018; Mynard et al., 2020; Mynard & Shelton-Strong, 2020; Yarwood, Lorentzen, et al., 2019), several significant changes have occurred in the intervening years. These changes include a generational shift in the student body, the increasing availability and familiarity with AI-assisted tools for language learning, and the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, where the SALC restricted some of its services and social activities for more than two years, altering the established norms, for example, the regular users who were role models and mentors moved on. Students noticeably spend more time on digital media consumption on individual devices than before. Although one of the goals of the SALC is to provide language practice opportunities for students, the present research shows that SALC users are using less English in the SALC than before 2020, yet seem mostly satisfied with this. Analyzing the reasons will help university staff consider what support is needed to meet the needs and expectations of students belonging to Generation Z (i.e., people born between 1995 and 2010 in Japan, according to Sakashita, 2020). According to Chen (2024) and Francis (2019), world events, AI, and financial and career insecurities have affected the priorities and actions of Generation Z people. Through this exploration, the authors hope to contribute to a deeper understanding of how institutional policies and practices can effectively promote language learner autonomy and support autonomous target language use in self-access environments for new generations of users.

Background information

Context

The setting for this study is the SALC at KUIS. The university is situated 40 minutes by train from Tokyo in Eastern Honshu. It is a relatively small university with just under 4,000 undergraduate students majoring in languages, international cultures, and global liberal arts. All of the students study English. First- and second-year students take foundational courses in English. Third- and fourth-year students can choose from a variety of content and language integrated learning (CLIL) courses that focus on many different subjects and academic disciplines taught in English. The majority of the students are Japanese nationals, but there are approximately 100 international students taking semester-long Japanese language and culture courses or full degree programs alongside the Japanese students.

The Self-Access Learning Center (SALC)

The SALC, originally established in 2001, is a supportive and inclusive social learning community dedicated to promoting language learner autonomy and language use (Mynard et al., 2022). The large, centrally located two-floor facility (the SALC’s third iteration) is located in the university’s eighth building (KUIS 8) alongside classrooms and staff offices. SALC use is optional, and it is a lively multipurpose space, receiving around 1,000 student visitors each day. On a typical day, a visitor might observe many of the following: students sitting in groups to study or socialize; students sitting alone doing homework or independent study; one-to-one advising sessions; student staff members assisting SALC users in English; lunchtime workshops focusing on language, autonomous learning, or culture; student-led events and learning community meetings; poster exhibitions based on class projects; group conversations in English at the English Lounge; students consulting various text and media materials; student-to-teacher language consultations with teachers on the second floor; one-to-one language exchanges (in more than 10 languages) with international students; and many other activities. (See https://kuis8.com for more examples of activities and Kushida and Mynard (2024) for a breakdown of the activities the participants of this study engaged in.) The SALC employs 12 full-time learning advisors (at the time of writing) who facilitate reflective dialogue (Kato & Mynard, 2016) and support learner autonomy through advising sessions, classroom visits, self-directed learning courses, workshops, and other SALC activities.

The English Language Institute (ELI)

The English Language Institute (ELI) is dedicated to promoting the English language through teaching courses in all university departments. ELI lecturers work with learning advisors as partners in facilitating in-class activities focused on reflective practice and related learning skills. Lecturers also provide outside-class language support for students in the SALC in the writing center, English conversation center, conversation lounge, and in conjunction with ‘maker’ conversation activities (cf. Taube-Shibata & Lorentzen, 2023). In this paper, the term ‘the SALC’ includes the spaces dedicated to outside-class support, including areas and language support services run by ELI lecturers and SALC learning advisors.

Supporting English With an Intentional Language Policy

SALCs are often places dedicated to target language practice (Thornton, 2018). Depending on the context, there are benefits to having a clear language policy in line with a SALC’s mission, leaving room for interpretation by users as they negotiate their identities within a space (Thornton, 2020). The policies themselves are likely to be determined by a combination of stakeholder beliefs, understanding of theories relevant to language education, and user preferences (Thornton, 2018). However, sometimes the policies are driven by social norms rather than strict policies (Thornton, 2020). Many SALCs worldwide have an explicit policy of encouraging target language use to provide language practice opportunities where they do not otherwise exist (Thornton, 2018).

The current SALC opened in 2017 and is the third iteration. The language policy was established in the two-story space as follows: English only on the second floor, and multiple languages and translanguaging encouraged on the first floor. This policy acknowledges the role of multilingualism in language education (Wongsarnpigoon & Imamura, 2020) and the importance of understanding learners’ affective and psychological factors (Mynard, 2023). In the previous and smaller second iteration of the SALC (2003 to 2017), there was a strictly enforced English-only policy, which was largely adhered to. However, this policy was off-putting for many potential users who lacked the confidence or willingness to use English outside of class, so they avoided the SALC as its use was optional.

The policy in the new SALC was established based on research that was conducted prior to moving into KUIS 8, gathering input from all stakeholders (students, faculty, and staff). However, despite the desire to use English ‘in theory,’ the actual use of English dropped when moving into the new building in 2017 (Imamura, 2018). The extensive space of the new SALC made it more difficult to support English language use everywhere, which was something that had been manageable in the previous version of the SALC. Since Imamura’s (2018) study, the SALC team has noticed that the number of students speaking English on the second floor has dropped further in recent years. The SALC team felt that it was time to revisit this policy, starting with input from current users. The SALC team takes a supportive rather than prescriptive approach to learning in line with the mission statement (see Mynard et al., 2022). Any change in language policy should still allow students to exercise their autonomy and make choices about the languages they use. The published SALC mission (Mynard et al., 2022, p. 33) is:

… to facilitate prosocial and lifelong autonomous language learning within a diverse and multilingual learning environment. We aim to provide supportive and inclusive spaces, resources and facilities for developing ownership of the learning process. We believe effective language learning is achieved through ongoing reflection and takes variables such as previous experiences, interests, personality, motivations, needs and goals into account and promotes confidence and competence when studying and using an additional language.

Theoretical Framework

Self-Determination Theory

Self-determination theory (SDT), developed by Deci and Ryan (1985), serves as the theoretical framework for this study. SDT provides a robust model for exploring human motivation and wellness, particularly through one of its mini-theories, basic psychological needs (BPNs) theory, which emphasizes the essential components of autonomy, relatedness, and competence for growth and engagement. Autonomy is self-endorsed decision-making and taking actions that align with one’s inner philosophy. Competence is a feeling of effectiveness. Relatedness is a sense of belonging and being valued by others. These three BPNs are intentionally supported in the SALC through advising sessions, language consultations, self-directed learning support, and community events (Mynard, 2022; Mynard & Shelton-Strong, 2020, 2022). SDT stresses the importance of autonomy-supportive interactions, quality relationships, and optimal structure (Reeve, 2021), all of which are embedded in the SALC design.

Motivations for Using (and Not Using) SALCs

There are a number of reasons why students choose to use a SALC, for example, for pragmatic reasons related to exam preparation or job hunting (Mayeda et al., 2008), but the main reason that students continue to engage in self-access is to develop friendships (Hobbs & Dofs, 2017; Hughes et al., 2011; Murray et al., 2014; Murray & Fujishima, 2013, 2016). Some studies have also investigated reasons for students not to use a SALC or a designated social learning space (e.g., McCrohan et al., 2024; Mynard et al., 2020), which might be due to genuine time constraints, inaccessibility, space constraints, or psychological barriers (see the next section).

Barriers to Using SALCs

Psychological barriers affecting target language use are a widely researched area of applied linguistics, and a full literature review cannot be included in this paper due to space limitations. Several studies in SALCs in Japan (e.g., Gillies, 2010; Kushida, 2018; McCrohan et al., 2024; Mynard et al., 2020; Suzuki & Hooper, 2024; Yamamoto & Imamura, 2020) have identified students’ feelings of anxiety when contemplating SALC use. According to those studies, this anxiety is often related to social factors (e.g., not feeling like part of the community), communication anxiety (e.g., perceived lack of English communication skills), negative comparison with others, and fear of negative evaluation by others. Non-use of a SALC due to social and psychological reasons highlights how important the BPNs of relatedness and competence are. When relatedness and competence are not being satisfied, this may lead to individuals feeling a lack of autonomy to engage in opportunities for—particularly social—activities in a SALC (Mynard & Shelton-Strong, 2020).

Understanding barriers and motivations is important, and this should ideally lead to attempts to help students capitalize on their interests and motivations and overcome barriers through further support and interventions. This is an ongoing endeavor; for example, helping students to reflect deeply and understand themselves through reflective dialogue (e.g., advising; Kato & Mynard, 2016; Shelton-Strong, 2020), prompting learners to set challenges for themselves (e.g., MacDonald & Thompson, 2019), using tools to help students identify a root cause and take action (e.g., Curry, 2014), creating opportunities for student leadership (e.g., Mynard et al., 2020; Watkins, 2022), supporting student-led learning communities (e.g., Hooper, 2025; Marzin & Raluy, 2024; Watkins, 2022; Yamamoto & Imamura, 2020), engaging learners in classroom-based discussions about outside-class learning (e.g., Yarwood et al., 2019), and providing scaffolding for participation through linguistic support (Mynard & Shelton Strong, 2020).

The Present Study

The research questions covered a wide range of factors that would help the researchers understand why students feel satisfied or dissatisfied with their use of English (Section 1), the barriers and motivations for using (or not using) English in the SALC (Section 2), and the recommendations regarding the policy (Section 3). The following research questions were developed:

Section 1: Reasons for satisfaction/dissatisfaction with using English

1. What are some reasons that students feel satisfied with their use of English in the SALC?

2. What are some reasons that students feel dissatisfied with their use of English in the SALC?

Section 2: Barriers and motivations

3. What are students’ motivations for learning English?

4. What do students report to be the main barriers to using English in the SALC?

5. What are students’ recommendations for improving support for English language use in the SALC?

Section 3: Language policy

6. How strictly do students think the language policy should be enforced?

Methods

Participants

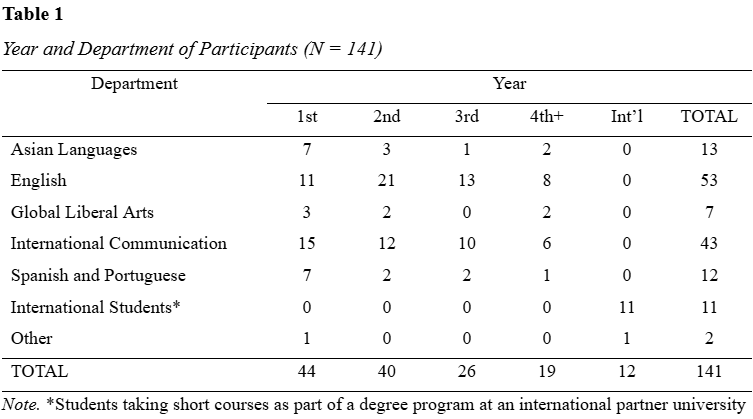

The participants were all KUIS students (both Japanese and international) using the SALC at some point during the two-week research period in July 2024. All but three of the participants used the SALC at least once a week, and 71 students (50.4% of participants) used the SALC every day. Table 1 shows a breakdown of students by department and year. Participants used the SALC to work on class-related tasks, study independently, communicate with other students in Japanese, English, or other languages, eat, relax, and play games (see Kushida and Mynard (2024) for more details). The university approved data collection, all students read the plain language statement and consent form and agreed to participate in the study, allowing the researchers to use their data for research purposes.

Interviews

The research team contained 19 researchers (the authors) from four different university departments who conducted 141 short, structured interviews (see Appendix) to investigate students’ attitudes toward language use and policy in the SALC. Interviews were chosen over surveys to target a more representative sample and to capture students’ voices better. The interviews, conducted in English, provided an authentic, enjoyable, and reflective language-learning opportunity for students while minimizing burden and bias. Semi-replicating a previous study (Asta & Mynard, 2018), the interview questions were adapted and refined to focus on language attitudes and policy, incorporating demographic and usage-related queries to enhance data interpretation. As in the previous study, the structured nature of the instrument meant that a large number of researchers could reach a large number of participants while ensuring a relatively consistent interview experience. Piloted with six students, the questions were further adjusted before a two-week interview period, with responses typed by the interviewers verbatim via a Google Form. (See Kushida and Mynard, 2024, for more details about the interview process.)

Data Analysis

Small teams of researchers (the authors) conducted a qualitative analysis of the data, tabulated some of the data, or presented it visually to highlight trends, and discussed the findings with the group. The process was inductive and interpretative in nature. The researchers also shared the results as a public poster in the SALC for several weeks and gathered written responses from students. Two of the researchers gathered written responses from 30 SALC student staff members and also conducted a one-hour focus group interview with four student staff members to discuss the results of the interviews in depth. All of these processes led to a deeper understanding of the findings. For the purposes of this paper, the authors mainly focus on English use in the designated English-only area, i.e., the second floor of the SALC.

Results

This section provides only the main findings. Ideally, each section needs its own detailed dissemination. However, for the purposes of this paper, a brief account of the main findings serves the purpose of sharing the main themes, supporting the language policy decision, and explaining interventions that are necessary.

Section 1: Reasons for Satisfaction/Dissatisfaction with Using English

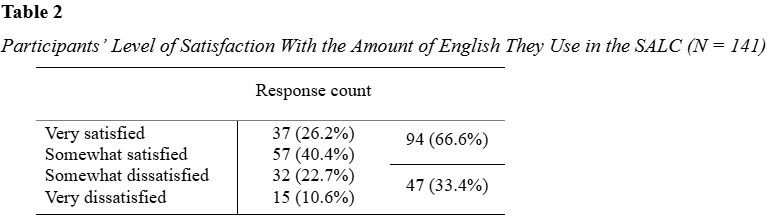

The data showed that generally, students use less English than students in previous years, with 61 students (43.3%) reporting using Japanese for most of their conversations on the second floor. However, satisfaction with their use of English has increased (see Kushida & Mynard, 2024; Kushida et al., 2024). Table 2 summarizes the breakdown.

What Are Some Reasons That Students Feel Satisfied With Their Use of English in the SALC?

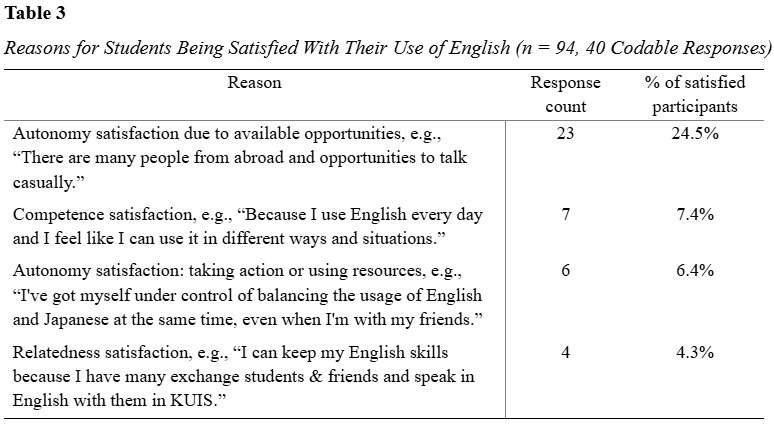

The reasons that some participants felt satisfied with their use of English are summarized, with example responses in Table 3. The data showed that around a quarter of the 94 participants who felt satisfied with their use of English in the SALC said that this was due to the available opportunities. A small number of students felt they could take self-endorsed and self-initiated action to use the available opportunities (n = 6), felt a sense of competence (n = 7), or a sense of relatedness (n = 4). Many students did not know why they felt satisfied, with 19 responses being too vague or irrelevant for the researchers to code, like in this example: “There are many spots we can study.”

What Are Some Reasons That Students Feel Dissatisfied With Their Use of English in the SALC?

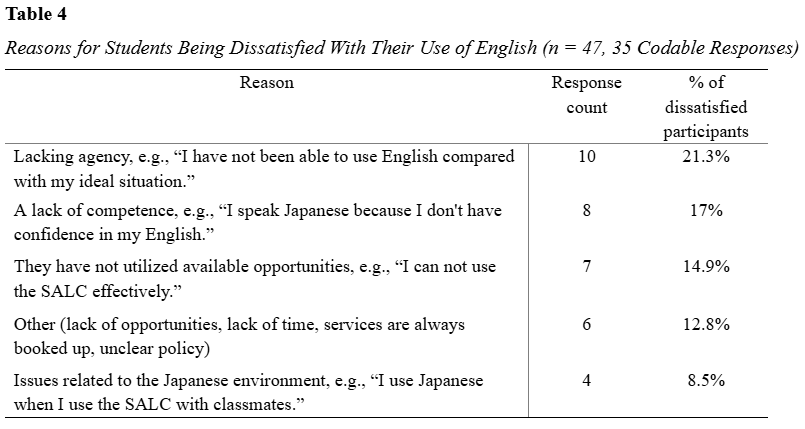

The analysis of interview data for the 47 students who were dissatisfied with their use of English indicated that their BPNs were not always satisfied. Table 4 shows that more than 20 percent of these students lacked agency. Others lacked a sense of competence (n = 8), were aware that they did not use the available SALC opportunities (n = 7), felt they lacked time or opportunities (n = 6), or had other issues (n = 4).

The results in this section indicate that students who were satisfied with their use of English felt that their BPNs were being satisfied in the SALC, and, in particular, had opportunities to exercise their autonomy. The opposite appeared to be true for students who were dissatisfied with their use of English.

Section 2: Motivations and Barriers

What Are Students’ Motivations for Learning English?

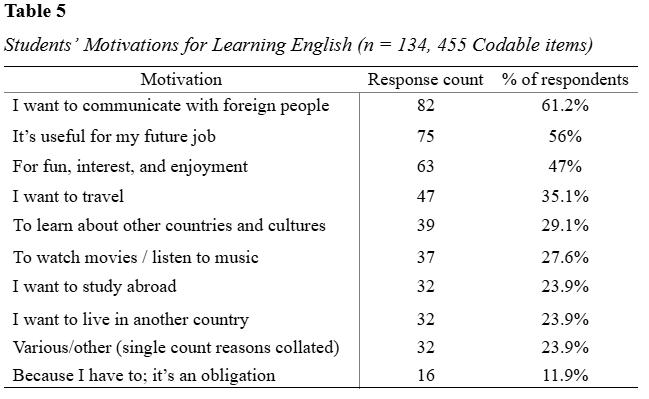

Students were asked about their reasons for learning English and usually listed several during the interview, totaling 455 items (see Table 5). The top responses were related to communication with others (61.2%), future employment opportunities (56%), and ‘for fun’ (47%). Only 11% cited English as an ‘obligation.’

Results in this section reveal that students’ motivation for using English was high, and most students had a mixture of intrinsic and extrinsic motives. Nevertheless, there are still significant barriers to actually using English in the SALC, which will be explored in the next section (research question 4).

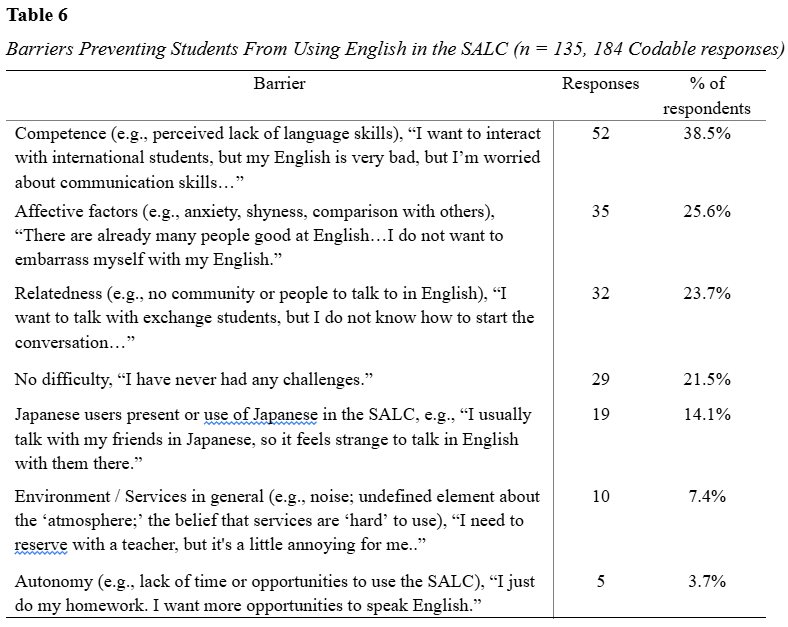

What Do Students Report to Be the Main Barriers to Using English in the SALC?

Although motivation was high and many learners felt they had opportunities to use English in the SALC, almost 80 percent of the participants reported that a range of barriers prevented them from actually using English in the SALC. Whereas ideally, a SALC supports learners’ BPNs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, the data indicated that although students did feel a sense of autonomy, elements of the second floor did not satisfy the BPNs of competence (53 respondents) and relatedness (32 respondents). In addition, 35 participants cited affective factors as barriers, and 10 respondents cited environmental factors (see Table 6). Nineteen respondents mentioned that being in an environment where most people are already speaking Japanese or going with friends with whom they usually use Japanese is not conducive to using English. Just over one-fifth of the 135 respondents to this question (29 participants) stated that they did not experience any particular challenge in using English in the SALC.

What Are Students’ Recommendations for Improving Support for English Language Use in the SALC?

The recommendations for improved support tended to fall into the domain of relatedness (the most frequent response, mentioned in 76 of 163 codable responses), i.e., the need to experience a sense of belonging and connection with others. The most popular recommendation for both floors of the SALC was a request for more events, as this interview excerpt demonstrates: “More events, we don’t have any chances to speak English with teachers or international students. We only have chances to speak in the classroom. Something like karaoke with English songs or fireworks with teachers and international students.”

Overall, participants requested few to no changes for the first floor, keeping it a multilingual space where they could talk freely in whichever language they chose. There was also a keen interest from students in having others (teachers, SALC student staff, peers) approach them rather than having them take the initiative to start English conversations.

Section 3: Language Policy

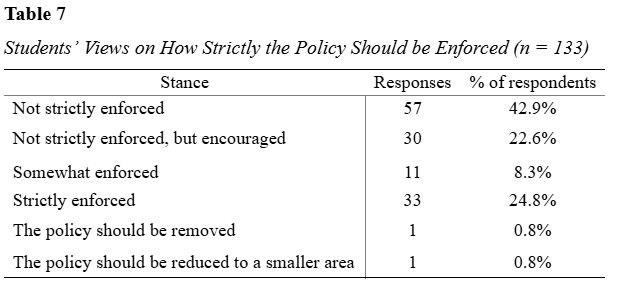

As noted previously (Kushida & Mynard, 2024), 126 participants (89.4%) approved of a language policy, at least in theory. The final research question explored students’ views on how strictly it should be followed.

How Strictly Do Students Think the Policy Should Be Enforced?

The most common response regarding the language policy was that it should not be strictly enforced (see Table 7). Although 44 students suggested a need for stricter enforcement of the existing policy, 89 participants said the SALC should opt for a more flexible approach (English as much as possible or English only in some areas of the second floor, for instance) to be more inclusive for all students, such as lower-proficiency students or international students learning Japanese.

Limitations

There are two limitations to this study. The first is the participants’ interpretation of the term ‘using English.’ This did not become apparent until the data analysis stage, but would need to be rectified for any future studies. Whereas the researchers usually interpreted ‘use of English’ to mean spoken English, some of the participants appeared to interpret ‘use of English’ as anything they did in English, which might include completing English homework by themselves, watching a video in English, or hearing other people speaking English. Secondly, the data presented in this study only relates to SALC users’ responses. SALC researchers administer an online survey with similar items to the general student population each year, and the 2024 survey revealed similar results to the interview study reported here (SALC, 2024). However, the general population survey is anonymous and is completed by less than 10% of the student body. In addition, respondents tend to be mainly frequent SALC users. There are plans to conduct systematic research with SALC non-users in the near future.

Discussion

The research shed light on SALC users’ views on their use (or non-use) of English and led to some findings that were useful for reviewing the SALC language policy. Firstly, the analysis of the interview data indicates that SALC users are motivated to learn English. Comparing past survey results accurately to the current survey was not fully possible due to the question format and answer choices changing over time. However, the results reported by Asta and Mynard (2019) and Yarwood, Lorentzen, et al. (2019) show that, in general, motivations have maintained similar trends over time. It appears that the COVID-19 pandemic, technological trends, and generational shifts have had little or no effect on KUIS students’ motivations for learning English. Their motives indicate a genuine interest in learning English as an enjoyable and meaningful endeavor, and they make autonomous decisions to come to the SALC.

However, a large number of people stated that they do not take the opportunity to actually use English while in the SALC, and many participants were satisfied with this and used the SALC for different purposes, e.g., to socialize with friends in Japanese (Kushida & Mynard, 2024). The reasons stated for not using English in the SALC, particularly on the second floor, related to lack of competence, negative affective factors, and lack of personal agency, which affected their sense of autonomy and willingness to use English. A perceived lack of competence was reported in previous studies in our context (e.g., Curry, 2014; Mynard et al., 2020) and has been cited by researchers elsewhere (e.g., McCrohan et al., 2024; Suzuki & Hooper, 2024) and is still a challenge that SALC practitioners need to investigate further.

Another factor that has surfaced in previous studies in our context (e.g., Asta & Mynard, 2019) is that some students claim that they lack opportunities to interact with teachers. Because of this view, such students have requested more events and activities. However, the SALC already offers daily events and regular activities that promote speaking, including opportunities to speak to teachers, but seemingly, students, even regular users, are not always aware of these. Despite these challenges, many students felt their BPNs were being satisfied, and they appreciated the freedom they had to take autonomous action and participate in SALC events and services as they wish.

After discussing the findings as a group and gathering additional insights and ideas from colleagues, students, and focus group participants, the researchers suggest that there should be no change to the current policy, i.e., to keep English only on the 2nd floor and do not enforce or monitor it (but continue to encourage and support it). However, more efforts are needed on the part of staff and students to encourage and support the use of English on the second floor. The multilingual policy on the first floor requires no further action as users are satisfied with the current policy.

Conclusions and Implications

The data showed that many participants perceived the SALC as an autonomy-supportive space with ample opportunities for English language use. However, by analyzing the interview responses, the researchers identified several interventions that could greatly enhance the learners’ experience with using the target language, particularly by supporting them in accessing communities and developing a feeling of language competence.

Some interventions are already underway. These include 1) communicating with colleagues and students throughout the university about the results of the study, 2) enlisting their help in maintaining an English-only space as much as possible on the second floor, 3) encouraging teachers to use class time to help learners prepare to use the second floor, 4) reintroducing an adapted form of the linguistic-risk-taking passport (MacDonald & Thompson, 2019) to help students set achievable challenges for themselves through micro-actions and habit building, 5) supporting students’ language competence with linguistic tools available in the conversation areas of the SALC, 6) creating short videos demonstrating strategies for using the conversation lounge, 7) recruiting and training student discussion-group facilitators (e.g., Garnica & Mislang, 2022), 8) supporting students in using the conversation lounge, e.g., as optional homework (Kiyota, 2021), 9) expanding the activities offered by teachers, and 10) having teachers available at lunchtimes for casual drop-in conversations in English. Many of the interventions will operate as action research projects, continuing to gather input from users. Ideally, this project should be replicated at a later date to research whether the interventions have been successful. An important point to bear in mind is that any interventions will be more successful if students themselves are involved.

As the interventions take shape, the researchers need to be mindful of the generation shift evident in Japan and take cues from other fields to meet students’ needs or tap into their motivations or preferences. For example, impactful marketing to young people in Japan is reported to use social platforms that make heavy use of visuals and involve user participation (Francis, 2019). Interactive and immersive experiences are popular among this generation, as are virtual concerts, interactive online events, and augmented reality experiences (Ulpa, 2024). Young people in Japan are also reported to be technologically savvy (Chen, 2024) and time-efficient consumers of content by, for example, only viewing highlights, skipping the main text, or checking spoilers (Lou, 2023) due to a phenomenon known as タイパ (taipa or time performance). Traditional promotional methods such as posters, signage, print-based worksheets, and brochures may not be as effective as in the past and might need to be updated, augmented, or replaced.

This project highlights the ongoing nature of self-access research and its multifaceted nature. Generational shifts and the impacts of technology and world events should continue to be monitored, and SALC practices should be adapted accordingly. Still, over time, findings at KUIS and elsewhere have consistently pointed to the necessity of supporting the three BPNs, particularly in helping learners manage negative affect and making it easier for them to access communities of language users.

Notes on the Contributors

At the time of writing, all 19 authors were employed as language educators at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) in Chiba, Japan. They have an interest in self-access, social learning spaces, and facilitating autonomous language learning outside the classroom. They are all members of a specially formed and autonomous research group concerned with supporting language proficiency and confidence in the large social learning space at KUIS. For more details of the social learning space, see https://www.kuis8.com and for details of ongoing research, see https://kuis.kandagaigo.ac.jp/rilae/

References

Asta, E., & Mynard, J. (2018). Exploring basic psychological needs in a language learning center. Part 1: Conducting student interviews. Relay Journal, 1(2), 382–404. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010213

Chen, Z. (2024, July 16). The satori generation: Minimalism and economic caution in modern Japan. Woke Waves. https://www.wokewaves.com/posts/satori-generation-japan-minimalism-economic-caution

Curry, N. (2014). Using CBT with anxious language learners: The potential role of the learning advisor. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.37237/050103

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

Francis, M. (2019, September 5). Japan’s Gen Z: 5 points about the enlightened ‘Satori generation’. Tokyoesque. https://tokyoesque.com/japan-gen-z-the-satori-generation/

Garnica, A., & Mislang, R. (2022). Student perceptions of interactions with non-native English student interns at a Japanese university’s multipurpose English center. JASAL Journal, 3(1), 96–120. https://jasalorg.com/student-perceptions-of-interactions-with-non-native-english-student-interns-at-a-japanese-universitys-multipurpose-english-center/

Gillies, H. (2010). Listening to the learner: A qualitative investigation of motivation for embracing or avoiding the use of self-access centers. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(3), 189–211. https://doi.org/10.37237/010304

Hobbs, M., & Dofs, K. (2017). Spaced out or zoned in? An exploratory study of spaces enabling autonomous learning in two New Zealand tertiary learning institutions. In G. Murray & T. Lamb (Eds.), Space, place and autonomy in language learning (pp. 201–218). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781317220909-13

Hooper, D. (2025). Students’ narrative journeys in learning communities: Mapping landscapes of practice. Candlin & Mynard. https://doi.org/10.47908/36

Hughes, L. S., Krug, N. P., & Vye, S. (2011). The growth of an out-of-class learning community through autonomous socialization at a self-access center. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 2(4), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.37237/020405

Imamura, Y. (2018). Adopting and adapting to new language policies in a self-access centre in Japan. Relay Journal, 1(1), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010120

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

Kiyota, A. (2021). Group dynamics and resilience in the process of L2 socialization: A longitudinal case study of Japanese university students visiting an English lounge. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 12(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.37237/120103

Kushida, B. (2018). Motivational factors in students’ non-use of a conversation practice center. Gengo Kyouiku Kenkyuu [Language Education Research], 29, 49–70. https://kuis.repo.nii.ac.jp/record/1595/files/SLLT_29_49_70.pdf

Kushida, B., Jingxin, H., MacDonald, E., & Mynard, J. (2024, October 26). Collaborative research on English usage in a self-access center [Conference session]. Japan Association for Self-Access Learning 2024 National Conference, Tokyo, Japan.

Kushida, B., & Mynard, J. (2024). Investigating language use and attitudes towards language policy in a self-access language center: A collaborative interview project. JASAL Journal, 5(2), 4–28. https://jasalorg.com/investigating-language-use-and-attitudes-towards-language-policy-in-a-self-access-language-center-a-collaborative-interview-project/

Lou, J. (2023, December 14). Spoiler alerts and double speed: The Japan gen Z’s unique approach to content consumption. Medium. https://medium.com/@jamie_aix/spoiler-alerts-and-double-speed-the-japan-gen-zs-unique-approach-to-content-consumption-885170684e34

MacDonald, E., & Thompson, N. (2019). The adaptation of a linguistic risk-taking passport initiative: A summary of a research project in progress. Relay Journal, 2(2), 415–436. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020216

Marzin, E., & Raluy, D. (2024). Communauté étudiante: Apprendre des autres et avec d’autres [Student community: Learning from and with others]. Mélange CRAPEL, 45(2), 71–96. https://www.atilf.fr/wp-content/uploads/publications/MelangesCrapel/Melanges_45_2_5_Pratique_2_Marzin_Raluy_pages_71-96_VF.pdf

Mayeda, A., Komori, M., & Fujisawa, Y. (2008). Discovering our self-access center: From in-country research to a working model. Ōsakashōinjoshidaigaku ronshū dai, 45, 53– 62. https://osaka-shoin.repo.nii.ac.jp/record/2095/files/KJ00004877026.pdf

McCrohan, G., Perkins, G. E., & Billa, D. G. (2024). Investigating a negative: Student non-use of a self-access centre. JASAL Journal, 5(1), 45–63. https://jasalorg.com/investigating-a-negative-student-non-use-of-a-self-access-centre/

Murray, G., & Fujishima, N. (2013). Social language learning spaces: Affordances in a community of learners. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 36(1), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1515/cjal-2013-0009

Murray, G., & Fujishima, N. (2016). Understanding a social space for language learning. In G. Murray & N. Fujishima (Eds.), Social spaces for language learning: Stories from the L-café (pp. 124–146). Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-53010-3_18

Murray, G., Fujishima, N., & Uzuka. M. (2014). Semiotics of place: Autonomy and space. In G. Murray (Ed.), Social dimensions of autonomy in language learning (pp. 81–99). Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137290243_5

Mynard, J. (2022). Reimagining the self-access centre as a place to thrive. In J. Mynard & S. J. Shelton-Strong (Eds.), Autonomy support beyond the language learning classroom: A self-determination theory perspective (pp. 224–241). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788929059-015

Mynard, J. (2023). Autonomy-supportive self-access learning: Meeting the needs of our students. In K. Schwienhorst & J. Ramos-Gonzalez (Eds.), Making space for autonomy in language learning (pp. 20–36). Candlin & Mynard. https://www.candlinandmynard.com/nordic14.html

Mynard, J., Ambinintsoa, D. V., Bennett, P. A., Castro, E., Curry, N., Davies, H., Imamura, Y., Kato, S., Shelton-Strong, S. J., Stevenson, R., Ubukata, H., Watkins, S., Wongsarnpigoon, I., & Yarwood, A. (2022). Reframing self-access: Reviewing the literature and updating a mission statement for a new era. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 13(1), 31–59. https://doi.org/10.37237/130103

Mynard, J., Burke, M., Hooper, D., Kushida, B., Lyon, P., Sampson, R., & Taw, P. (Eds.) (2020). Dynamics of a social language learning community: Beliefs, membership and identity. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788928915

Mynard, J., & Shelton-Strong, S. J. (2020). Investigating the autonomy-supportive nature of a self-access environment: A self-determination theory approach. In J. Mynard, M. Tamala, & W. Peeters (Eds.), Supporting learners and educators in developing language learner autonomy (pp. 77–117). Candlin & Mynard. https://doi.org/10.47908/8/4

Mynard, J., & Shelton-Strong, S. J. (2022). Self-determination theory: A proposed framework for self-access language learning. Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning, 4(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.52598/jpll/4/1/5

Reeve, J. (2021, December 3). Encouraging autonomy and agency in a SALC: Three suggestions [Featured presentation]. 7th LAb Session: Agency and Learner Autonomy, Chiba, Japan. https://kuis.kandagaigo.ac.jp/rilae/lab-sessions/lab7/

SALC (2024). Unpublished findings from the KUIS 8 2024 survey. Kanda University of International Studies, Japan.

Shelton-Strong, S. J. (2020). Advising in language learning and the support of learners’ basic psychological needs: A self-determination theory perspective. Language Teaching Research, 26(5), 963–985. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820912355

Sakashita, M. (2020). Generation Z in Japan: Raised in anxiety. In E. Gentina & E. Parry (Eds.), The new generation Z in Asia: Dynamics, differences, digitalisation (The changing context of managing people) (pp. 55–70). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80043-220-820201007

Suzuki, K., & Hooper, D. (2024). Self-access anxiety through the eyes of students. JASAL Journal, 5(1), 4–27. https://jasalorg.com/analyzing-self-access-anxiety-through-the-eyes-of-students/

Taube-Shibata, J., & Lorentzen, A. (2023). Maker conversation: Successes and challenges in a university SALC. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 14(2), 232–239. https://doi.org/10.37237/140207

Thornton, K. (2018). Language policy in non-classroom language learning spaces. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 9(2), 156–178. https://doi.org/10.37237/090208

Thornton, K. (2020). Student attitudes to language policy in language learning spaces. JASAL Journal, 1(2), 3–23. https://jasalorg.com/thornton-student-attitudes/

Ulpa. (2024, November 2). Mastering youth culture: The increasing influence of Gen Z in Japan. https://www.ulpa.jp/post/mastering-youth-culture-the-increasing-influence-of-gen-z-in-japan

Watkins, S. (2022). Creating social language learning opportunities outside the classroom: A narrative analysis of learners’ experiences in interest-based learning communities. In J. Mynard & S. J. Shelton-Strong (Eds.), Autonomy support beyond the language learning classroom: A self-determination theory perspective (pp. 182–214). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788929059-009

Wongsarnpigoon, I., & Imamura, Y. (2020). Nurturing use of an English speaking area in a multilingual self-access space. JASAL Journal, 1(1), 139–147. https://jasalorg.com/journal-june20-wongsarnpigoon-imamura/

Yamamoto, K., & Imamura, Y. (2020). Taiwa no naka de seichou suru gakushuusha ootonomii: Serufu akusesu sentaa ni okeru shakaiteki gakushuu kikai no kousatsu [Developing learner autonomy through dialogue: Considering social learning opportunities in self-access centers.] In C. Ludwig, M. G. Tassinari, & J. Mynard (Eds.), Navigating foreign language learner autonomy (pp. 348–377). Candlin & Mynard.

Yarwood, A., Lorentzen, A., Wallingford, A., & Wongsarnpigoon, I. (2019). Exploring basic psychological needs in a language learning center. Part 2: The autonomy-supportive nature and limitations of a SALC. Relay Journal, 2(1), 236–250. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020128

Yarwood, A., Rose-Wainstock, C., & Lees, M. (2019). Fostering English-use in a SALC through a discussion-based classroom intervention. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 10(4), 356–378. https://doi.org/10.37237/100404

Appendix

Structured questionnaire

1. Participant background

Which year are you in at KUIS?

Which department are you in?

How often do you currently use the 1st floor of KUIS 8 (excluding classes and working time)?

If you never or hardly ever use the 1st floor, can you tell us why not?

What, if anything, do you do on the 1st floor of KUIS 8? (Multiple answers possible.)

How often do you currently use the 2nd floor of KUIS 8 (excluding classes and working time)?

If you never or hardly ever use the 2nd floor, can you tell us why not?

What, if anything, do you do on the 2nd floor of KUIS 8? (Multiple answers possible.)

2. Language goals

Are you learning English at the moment?

If no, are you a native-level speaker of English?

If yes (to the question “Are you learning English”), why are you studying English? (What are your motivations?) (Multiple answers possible.)

3. English Use

Who, if anyone, do you enjoy speaking English within KUIS 8? (Multiple answers possible.)

On average, what percentage of the time do you use English on the 1st floor of KUIS 8 (excluding classes and working time)? (Likert scale 0 to 100%)

On average, what percentage of the time do you use English on the 2nd floor of KUIS 8 (excluding classes and working time)? (Likert scale 0 to 100%)

Are you satisfied with the amount of English you use in KUIS 8? (Multiple choice: Very satisfied / Somewhat satisfied / Somewhat dissatisfied / Very dissatisfied)

Do you face any challenges or difficulties when using English in KUIS 8? If yes, what are they? (Multiple answers possible.)

4. Language Policy

Did you know that there is a language policy on the 2nd floor?

If yes – What do you understand about the policy?

The policy is that students should use English only on the second floor. What is your opinion about the policy? (prompt if needed: Do you think we should change it? What should the policy be?)

In your opinion, how strictly should the policy be enforced? (Prompt if necessary: Should we force students to use English on the 2nd floor?)

What, if anything, should we do to enforce it? (Prompt if necessary: Should we force people to use English? How should we do that?)

5. Suggestions

What, if anything, could we do to help students use more English on the 2nd floor?

What, if anything, could we do to help students use more English on the 1st floor?

I was delighted to read this paper, as I visited the SALC last year and was impressed by its warm, welcoming atmosphere and the commitment to supporting learner autonomy. The challenges you describe, especially responding to generational changes, are similar to those we face at my university.

The use of Self Determination Theory provides strong theoretical grounding. I wondered though if the coding into autonomy, competence, and relatedness could be explained in a little more detail, as this would help readers understand how the themes were applied. It might also be interesting to relate the high motivation reported more explicitly to these three needs.

The discussion of Generation Z learners seems central to the overall argument, though it feels somewhat disconnected from the study’s main focus and research questions. The ideas for more digital friendly practices in the conclusion are excellent. Linking these to the relatedness dimension of SDT would be a great way to show how these changes meet students’ psychological needs while making the SALC more accessible.

Thank you for your amazing work. In an age of rapid digital development, creating spaces that foster human connection and community through language learning feels more important than ever, and this is something the SALC does exceptionally well.

Dear Antonie,

Thank you very much for reading our paper and for your kind words. We are glad that the themes resonated with you, and we appreciate your questions and comments. We are grateful for the opportunity to respond to some of your points below.

We realise that the paper does not include detailed information about our data analysis and coding process, so we will add the necessary section to the final draft – thanks for highlighting it. We used self-determination theory to inform our analysis and coding. First, we determined which interview questions were suitable for analysis to help us understand students’ basic psychological needs (BPNs). Then, sub-teams conducted an interpretive analysis of the relevant interview data, identifying themes that emerged from the open-response items and coding them accordingly. We re-read the codes and responses and decided which codes were representative of one or more of the three BPNs (autonomy, competence, relatedness) for both satisfaction and thwarting, based on established definitions (e.g., Ryan & Deci, 2002, 2017). We counted the number of instances representative of each BPN being satisfied or thwarted and tabulated them. Responses often showed evidence of more than one BPN, while some responses did not represent any BPN but were still coded due to their relevance to the research question. Some responses were excluded from the coding due to ambiguity or irrelevance.

Regarding your comment, “It might also be interesting to relate the high motivation reported more explicitly to these three needs.” We assume you are referring to Table 5 (Students’ motivations for learning English). This was intended as background information, and we didn’t have enough data to explore from an SDT perspective; however, we were able to see a variety of motives that could broadly be interpreted as both intrinsic and extrinsic. The purpose of including this general data on motivation was to highlight that, in general, our students are motivated to learn English, yet they experience barriers to doing so in the SALC.

We acknowledge your point that the discussion about Generation Z isn’t tightly connected to the central theme; however, this paper resulted from our examination of change in general in our context, and it is really hard to ignore generational shifts. We use this paper as an opportunity to begin exmining what has been written elsewhere about generational shifts among learners in Japan. This helped us to speculate about the kind of support that could be provided and how we might grow to meet the changing needs of our learners. We appreciate your suggestion to link these ideas to the relatedness dimension, and we will revise this section accordingly. Thank you for the suggestion.

Thanks again for taking the time to read and respond to our work. We greatly appreciate it, and we hope you can visit our SALC again sometime.

Kind regards from the team at KUIS!