(Previously titled: Reflection Through Dialogue: Conducting a Mentoring Session with a Colleague Using the ‘Wheel of Reflection’ Tool)

Ewen MacDonald, Kanda University of International Studies

MacDonald, E. (2019). Reflection through dialogue: Conducting a mentoring session with a juku colleague using the ‘Wheel of Reflection’ tool. Relay Journal, 2(1), 45-59. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020106

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

This reflective article outlines a mentoring session conducted with a former colleague in which I took the role of a mentor. The aim of the session was to support my colleague to reflect on themselves as a teacher through engaging in reflective dialogue. To help facilitate this, an advising tool called the ‘Wheel of Reflection’ was used to help my colleague analyse their level of satisfaction for different aspects of their teaching, identify areas where they would like to improve their satisfaction level, and come up with an actionable plan for how to do this. In the article, I briefly discuss reflective dialogue and the purpose of mentoring. I then outline the flow of the mentoring session and what I did as a mentor to help facilitate the reflective dialogue. Finally, I reflect on the session, the benefits for myself and my colleague, and what I learnt from the process.

Reflection through dialogue

Critical reflection in teacher education can occur in many forms. It allows teachers to examine their values and beliefs about teaching and learning and gain new insights into their classroom actions. It can occur as both self-reflection through internal dialogue, as well as in dialogue with others. While self-reflection is easy to perform, learning is limited to one’s own insights and observing oneself critically is not always easy (Kato & Mynard, 2015). On the other hand, reflective dialogue with others, while more challenging, provides opportunities to discover new and different perspectives, and allows existing values, assumptions and beliefs to be challenged with the possibility for greater changes in these taking place (Kato, 2012; Kato & Mynard, 2015). This can lead to further professional development as a reflective practitioner.

Reflective dialogue in mentoring

One way to be a reflective practitioner as a teaching professional is by engaging in a mentoring relationship in which reflective dialogue with others takes place.

A traditional mentoring relationship may be seen as the transmission of knowledge and skills from an experienced successful mentor to an inexperienced junior mentee (Delaney, 2012), with the goal being to improve the performance and expertise of the mentee (Hobson, Ashby, Malderez & Tomlinson, 2009). However, Delaney (2012) notes that minimal attention is paid to the benefits for mentors in this traditional view. A more modern view of mentoring is a relationship where “both participants co-construct their professional identities within a specific context” (Delaney, 2012, p. 186). Through the mentor’s support and engagement in collaborative learning with the mentee, reflective practice can be fostered for both participants (Delaney, 2012). Research on reflective dialogue between mentors and mentees has shown the process to serve as an effective professional development opportunity for both participants by helping them engage in a transformative learning process (Kato, 2012, 2016).

Background to the mentoring session

As part of a learner autonomy course that I undertook on an MA TESOL program, I conducted a mentoring session with one of my colleagues in which I took on the role of a mentor and engaged with them in reflective dialogue. The primary aims were to support my colleague in reflecting deeply in order to develop further as a professional teacher, and to identify an “issue” in their teaching while guiding them to take action on this issue. An additional aim was to further my own development as a reflective practitioner through helping my colleague. Prior to the session, I had undertaken brief training in ten basic advising strategies used in the language learning advising field: repeating, restating, summarising, empathising, complimenting, metaview/linking, metaphor, powerful questions, challenging, and accountability (Kato & Mynard, 2016). During this training, I also had some hands-on practice in using these advising strategies with my classmates.

At the time of the session, my colleague Mari (a pseudonym) and I had been working together for over a year on an English Program at a juku (cram school) in Japan. We had a good working relationship and communicated regularly about our students and lessons. Mari was also an experienced teacher who had previously undertaken a postgraduate TESOL training course.

The ‘Wheel of Reflection’ tool

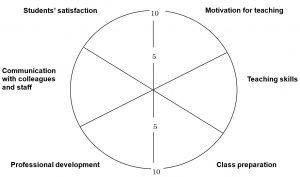

A tool called the ‘Wheel of Reflection’ (Kato, 2016) was used to help facilitate reflective dialogue in the mentoring session. The wheel consists of 6 areas in which the respondent ranks their current level of satisfaction for each area by drawing lines (see Figure 1). The outer edge of the wheel represents complete satisfaction while the centre represents complete dissatisfaction. The idea for this tool originated from the field of life coaching and was adapted for two other tools called the ‘Wheel of Language Learning’ (Kato & Sugawara, 2009; Yamashita & Kato, 2012) and the ‘Wheel of Learning Advising’ (Kato, 2012), developed for facilitating reflective dialogue with language learners and learning advisors respectively. Compared to text-based tools, the wheel as a visual tool allows the person completing it to identify how the different areas of the wheel are interconnected and can affect each other, and hence experience deeper reflective processes. It also allows them to take control of the reflective dialogue from the initial stage (Kato, 2012; Kato & Sugawara, 2009; Yamashita & Kato, 2012).

Figure 1. The Wheel of Reflection (Kato, 2016)

The mentoring session and the mentee’s reaction

I firstly asked Mari to complete the ‘Wheel of Reflection’ sheet and observed her doing this. I noticed that she took time to decide on her level of satisfaction for ‘Communication with colleagues and staff’. She also queried whether ‘Students’ satisfaction’ should be based on her assumption. Her desire to understand students’ feelings emerged later on in the session.

I then let Mari take the initiative in our dialogue by asking her to explain the Wheel. She began by talking about her high motivation that she has always had for teaching English. She quickly identified her self-described ‘dilemma’ which was a lack of communication with non-teacher colleagues involved in the primary decision-making of the juku.

Ewen: Could you explain your wheel of reflection?

Mari: Ok, first of all, motivation for teaching. I think I have always been highly motivated, and it hasn’t changed ever since I started working here.

Ewen: So you’ve always had a strong motivation.

Mari: Yes. But, because I have a dilemma that derives partly from the lack of communication, not with you, but with staff in general, okay.

Mari felt the lack of communication and also lack of time prevented her from using her motivation to improve her teaching skills, and that better communication would help her realise what is best for students and have a greater understanding of whether they are satisfied. She also mentioned past disappointments when attempting to communicate with the aforementioned staff which had led to this feeling. At this point of the session, she noted that all sections of the wheel were interconnected for her. As Mari spoke, I tried focusing on the words that she regularly used to describe her dilemma, and attempted to use advising strategies such as restating and summarising to show my understanding and deepen her self-reflective process.

Mari: … I think there are things that need to be improved about communication with staff in general, that’s why, and that is one of my dilemmas. Because of that, even though I’m highly motivated, I… can’t fully use that motivation to improve my teaching skills or classroom preparation aspect. Thus the result… professional development… maybe could have been better if this communication were improved as well.

Ewen: So it seems like every part of your wheel is interconnected.

Mari: They’re all interconnected yes.

Ewen: So just to confirm, you said you are highly motivated for teaching, but what was the connection between your motivation and teaching skills?

Mari: Okay, because I’d like to teach better and I’d like students to be satisfied more, I’d like to improve my teaching skills, but in order to do that I need time and better communication so I can realise what I think is best for students. That’s part of my teaching skills I think. But I feel that we have some limitations in terms of time and communication. My teaching skills have not been fully improved or developed as much as I want them to be.

[Omitted]

Mari: I need to know how students feel. I need to know whether they’re really satisfied, whether they have any requests or dissatisfaction, but for me to know that I wish that we could provide them with some kind of questionnaire.

[Omitted]

Ewen: So you’re not sure about the students’ level of satisfaction.

Mari: Umm, well about some students I’m sure because of some email communication with parents, they sometimes say their students are highly satisfied and like both of our lessons. But most of them we haven’t had a chance to talk to their parents or talk to them directly, so I don’t know.

During the session, I endeavoured to focus on Mari’s emotions as she spoke to show that I was listening carefully by nodding and making eye contact. I also attempted to use a powerful question in order to clarify Mari’s future vision that would help her find a possible solution.

Ewen: Ok, so you feel this communication issue would prevent you from doing the questionnaire and also the results wouldn’t make any changes to the wider curriculum?

Mari: Yes and no, because there are two things, lack of communication and amount of communication. But there is another one, even if there’s a lot of communication I think [other colleagues] and I will have lots of discrepancies in the way how we think, what we think is more effective for students to improve their English, because as you know, I believe less is more, but [another colleague] doesn’t think so. That’s a huge difference and I don’t know how to fill that gap.

Ewen: Is there anything you would like to learn from students that would affect the way you teach… what you would do in the classroom?

Mari: That’s a good question… that’s a good question… maybe not a questionnaire but I could ask students individually how they feel, maybe verbally, or I could email parents asking for their opinions, or I could even arrange, you know, conferences with students or with their parents. All of them are possible.

As Mari’s main issues were communication-related, which was accompanied by negative emotions, I accepted her emotions but also aimed to help her see the positive aspects despite the limitations she faced.

Ewen: So it seems you can still find your students’ feelings towards their English learning despite the limitations.

Mari: Yes I think so, that’s true. And actually whenever I feel there’s a problem with a student, I email… I have already, and told parents my concerns, you know, who has not been participating actively lately, yeah.

Further to this, Mari’s concern about her students’ learning was clear, so I complimented her on this to help her feel positive emotions.

Ewen: You really seem to care about students learning.

Mari: I do! Because, yeah I do care, that really affects my… yeah it’s not motivation, but as a professional I feel responsible for students… firstly I want students to enjoy lessons and I want students to feel more motivated about learning English… so I think that’s part of my responsibility, to make sure they do.

I also maintained a positive attitude throughout the session. Mari spoke of her disappointment with previous communication issues and its effect on her motivation, which I could see from her emotions. While acknowledging the issue and empathising with her, I tried to help her realise any previous positive successes that she had in communication with colleagues that had positively impacted on her motivation and professional development.

Ewen: So it seems like the issue stopping you from finding out about this is communication with staff.

Mari: Exactly.

[Omitted]

Ewen: Yeah, you are trying to be very positive, however the lack of communication is holding you back.

Mari: Yeah and it’s very unfortunate because there’s nothing wrong about communication, no one should be afraid about speaking up.

[Omitted]

Mari: But when there’s no meeting and we’re just given instructions what to do… sometimes I agree, sometimes I don’t agree with those instructions. And about things that I don’t fully agree with, maybe I feel less motivated.

Ewen: So the lack of communication sometimes affects your motivation.

Mari: Yes.

Ewen: Have you ever had positive experiences communicating with staff before?

Mari: Oh, I think so. With colleagues certainly yes. Every time I communicate with you or [another teacher] there’s always good communication and that helps my motivation and teaching skills and professional development I’m sure. And with communication with staff I think I’ve had quite a few good communications in the past.

Ewen: So you have had positive experiences communicating with staff?

Mari: Yes.

Ewen: And you seem to feel you are able to put your ideas forward even if they are refused or ignored.

Mari: Yes right.

As Mari believed there was nothing she could do to improve the communication with the non-teaching staff, I tried guiding her to focus on her students and her own development as a teacher. I encouraged Mari to make an informal plan to find out more about student satisfaction, despite her reluctance due to the aforementioned communication problems. Mari also asked for my advice at this point in the dialogue, based on action research I had carried out with the students.

Ewen: So you also mentioned student satisfaction. How do you think you can improve that area? I recall you mentioned earlier that you would like to know more about how students feel about the lessons.

Mari: Well, that I need to ask you actually, but do you think it’s a good idea for me to have my own questionnaire?

Ewen: Well, I feel after conducting my own questionnaire, I found it was very valuable in order to learn what students feel.

Mari: It would be for my own professional improvement.

Ewen: Would it help with your professional improvement?

Mari: Yes and no, because I would like to be able to share the results of the questionnaire with other staff and colleagues. And before that maybe I should, well I don’t think it should be personal so in formulating the questionnaire I think… the ideal I think it’s better to make the questionnaire together.

Although I was ultimately unable to help Mari set a plan to overcome her communication issue that she identified at the beginning of the session, I felt I was able to help her clarify her future vision of gaining a greater understanding of student satisfaction, and encourage her in coming up with an actionable plan of how she could do this with other teachers.

Ewen: However, you feel positive communicating with your teaching colleagues. Is that right?

Mari: Yes.

Ewen: Do you think it’s something you could do with your teaching colleagues?

Mari: Yes. Ok there are [number of] teachers mainly… among [the other] teachers I think we can communicate about whatever we’re going to do, for instance a questionnaire.

Ewen: Ok so do you think you can set a plan for what you want to do in order to find out more about student satisfaction?

Mari: Yeah… maybe I should, yes.

Ewen: What do you think you could do?

Mari: Umm… I don’t know when, but perhaps when they’re about to ascend from one level to another, perhaps I can ask them then.

Ewen: When will that happen next?

Mari: Well maybe the end of December when students graduate.

Ewen: Do you think you can ask those graduating students some general questions?

Mari: Yes, you know like what they think could be improved.

Ewen: Do you think that could affect other parts of the wheel?

Mari: Yes certainly. That would improve all areas, I mean… all areas, because I could even tell our higher staff what I’ve been told by the students for their reference at least. I don’t know if they’d really care about it, but I could tell them.

Ewen: You seem very positive thinking about if you could find out things from students, and it seems like it would make you more motivated.

Mari: Yes.

Ewen: And you can still communicate it to higher staff.

Mari: Yes I can try even if… I’ll never give up.

Ewen: You’ve always seemed to try to communicate regardless of the result even till now.

Mari: Yes, and I’ve been turned down several times but I’d still like to try.

Ewen: So as soon as?

Mari: The end of this month? Or the beginning of next month.

Post-session self-reflection

As I had only used advising strategies a few times informally before the session, I was still getting accustomed to focusing on both verbal and non-verbal aspects while utilising a variety of these strategies. I felt relatively comfortable using restating and summarising and attempted to ask Mari many thought-provoking questions. However, if I conducted an advising session again, I would aim to use more metaphor and powerful question strategies to promote deeper reflection. I found it challenging to use such strategies naturally during the dialogue.

After transcribing and reviewing the dialogue, I also felt that I did not always accurately summarise what Mari expressed, perhaps as I was struggling to focus on several different aspects at once. On reflection I could also have elaborated more on Mari’s strengths by using both summarising and complimenting together which would have brought more positivity into the session.

I would also endeavor to remain more neutral when considering and using advising strategies during the session. It is possible that I was influenced by my pre-existing knowledge of Mari’s problematic situation which led to me making suggestions that would find a way around the communication issue rather than attempting to improve it.

I felt that attending to Mari’s emotions during the session was perceived positively by her and helped establish a mutual understanding between us, allowing for open discussion. I was also pleased that closing with accountability in the final part of the session helped provide Mari with a positive course of action to pursue which she expressed confidence in trying.

The benefits of the process and what was learnt

Overall, I found that engaging in a reflective dialogue with a teaching colleague, in this case facilitated through a mentoring session using a ‘Wheel of Reflection’ tool, is beneficial for both people involved and can have a positive flow-on effect for students.

The wheel and dialogue helped Mari to establish her feelings and her visions which allowed her to engage in a deeper and more productive discussion with me after the session had finished. Mari remarked that the ‘Wheel of Reflection’ helped her “think logically” and through our reflective dialogue, she realised one of her strongest values, stating that “student satisfaction is the most important factor of all … it really affects everything else”. She also “realised that everything is interconnected” in regard to her satisfaction level for each area of the Wheel.

I was pleased that the session helped foster Mari’s teacher autonomy as she realised she could still take action to learn her students’ feelings despite the existing communication issues, and that this would have a positive effect on other aspects of her teaching. Her professionalism and care about her students and other teachers was clear, and she continued to hope for a better environment where students’ views could be understood and where all staff could communicate and support one another. I also believe that our strong professional working relationship and communication regarding classes and students on a daily basis allowed Mari to feel safe talking with me and open up during the session about many of her feelings.

Importantly, I was also able to reflect on my own beliefs as a language teacher after the mentoring process as I understood her situation and also had a wish to know students’ satisfaction to improve my own teaching practice. This was an area that I was often concerned about in my teaching at the time, and led to me conducting more action research and post-class questionnaires to discover my students’ feelings and beliefs.

To conclude, I strongly believe that reflection on teaching practices, whether in mentor and mentee roles or simply as colleagues engaging in day-to-day reflective dialogue together, is highly beneficial to sustain motivation and make informed decisions based on critical reflection.

Notes on the contributor

Ewen MacDonald is a graduate of the MA TESOL Program at Kanda University of International Studies. He previously taught in eikaiwa and juku in Japan, and currently teaches at a junior/senior high school and a vocational college. His research interests include pragmatics, learner autonomy, teacher cognition, and corrective feedback.

References

Delaney, Y. A. (2012). Research on mentoring language teachers: Its role in language education. Foreign Language Annals, 45(1), 184-202. doi:10.1111/j.1944-9720.2011.01185.x

Hobson, A. J., Ashby, P., Malderez, A., & Tomlinson, P. D. (2009). Mentoring beginning teachers: What we know and what we don’t. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25, 207-216. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.001

Kato, S. (2012). Professional development for learning advisors: Facilitating the intentional reflective dialogue. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(1), 74-92. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/march12/kato/

Kato, S. (2016, January). Promoting teacher autonomy through reflective dialogue: Establishing a mentoring framework. Poster session presented at the IAFOR International Conference on Education, Honolulu, HI.

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kato, S., & Sugawara, H. (2009). Action-oriented language learning advising: A new approach to promote independent learning. The Journal of Kanda University of International Studies, 21, 455-475. Retrieved from https://ci.nii.ac.jp/els/contentscinii_20181218151111.pdf?id=ART0008988887

Yamashita, H., & Kato, S. (2012). The wheel of language learning: A tool to facilitate learner awareness, reflection and action. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.). Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 164-169). Harlow, UK: Longman.

Dear Ewen,

I thought this article provided a fascinating perspective on the value of using advising tools to stimulate reflective practice in juku. I really appreciated that you carried out this study in a context outside of formal education as I felt that it shone a light on how despite teachers in juku or eikaiwa schools often being marginalized or overlooked in our field, if we look past unhelpful stereotypes we can see a remarkable depth of professionalism and integrity from these teachers. I also carried out a similar task during my MA with a colleague at the eikaiwa school I was working at and found it to be an extremely rewarding experience for both of us involved. This has in fact influenced our reflective practice group in KUIS where we often use the advising techniques in Kato and Mynard (2016) as well as the speaker-understander dynamic from Edge (2002) as they really help to promote non-judgmental reflection and trust. You may also be interested to look into Walsh and Mann’s (2017) model for reflective practice as they too greatly emphasize the need for dialogic reflection rather than the narcissistic navel-gazing or mindless box checking that reflection can degenerate into. Farrell (2018) also strongly advocates for participation in ‘critical friendships’ and teacher development groups so I think we’re definitely on the right track!

I do have some questions and suggestions related to your study. First, Mari often spoke about the lack of communication between the teaching and non-teaching staff in the juku. What do you think she was referring to and did you ever experience this yourself when you were there. I wondered if this could have been in part due to a conflict that I have highlighted in my own research between the parallel interests of business and education in contexts like eikaiwa and juku. If so, this might be an interesting tension to explore as it can have a profound impact on teacher identity, motivation, and stress (see Nuske, 2014 for some examples of this). Also, on many occasions Mari mentioned that she was deeply concerned with how her students felt about her classes and whether her instruction was meeting their needs. In the same spirit, I thought that it might have been nice to ask Mari for a reflection on how she felt the Wheel of Reflection activity went and whether it stimulated any realizations or breakthroughs in her. This could also be done like a member checking session where you run through your interpretations and check whether they were congruent with her perspective or not. One final question for you is, what constraints do you foresee for others who may want to encourage more reflective practice in non-formal contexts like juku or eikaiwa? Are there ways that you can think of for teachers to circumvent the structural constraints that these educators may experience?

I really enjoyed reading this study and it gave me hope for those teachers who many in the field have forgotten about. I really hope that we will be able to work on something together in the future in this area or on the topic of reflective practice in general.

References

Edge, J. (2002). Continuing cooperative development: A discourse framework for individuals as colleagues. University of Michigan Press.

Farrell, T. S. C. (2018). Reflective language teaching: Practical applications for TESOL teachers. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

Nuske, K. (2014) “It is very hard for teachers to make changes to policies that have become so solidified”: Teacher resistance at corporate eikaiwa franchises in Japan. The Asian EFL Journal 16 (2), 283-312.

Walsh, S., & Mann, S. (2017). Reflective practice in English language teaching: Research-based principles and practices. New York: Routledge.

Dear Daniel,

Thank you for your valuable feedback on my article. I agree with your suggestion for both participants to reflect to see if their interpretations align and will consider this when I have another opportunity to use an advising or reflective practice activity.

The lack of communication between teaching and non-teaching staff (management) is something I also experienced. This related to previous requests for meetings regarding teaching matters being deemed as unnecessary and turned down, or suggestions by teachers being ignored. In one case when a meeting was proposed in relation to several classroom-related issues, the issues raised were all deemed as “management issues” that a meeting with teachers would not help in making decisions for. This generally led to a reluctance by teachers to approach the non-teaching staff. I believe this was somewhat related to the parallel interests of business and education, and a desire in this particular case by non-teaching staff to feel in control. It is possible that as Mari and I were both teachers who had undertaken, or were undertaking, post-graduate teacher education courses, non-teaching staff may have felt that their identities were threatened when having something suggested to them. The poor communication certainly had an impact on teacher identity and motivation for myself and Mari and is something I will explore more in the future.

A constraint I foresee for promoting more reflective practice in eikaiwa or juku is that it is generally not something encouraged or an established part of these teaching contexts (at least from my own experience and knowledge). While eikaiwa instructors may undergo initial and follow-up training (which is sometimes considered to be inadequate), I feel most reflective dialogue and sharing of ideas occurs in informal situations outside the classroom. Furthermore, depending on the size and type of school, some educators may be quite isolated. After I left the juku, Mari expressed her pity that she was no longer able to discuss lessons with the new teacher as their schedules (in order to suit business interests) meant they spent little time with one another before lessons.

To circumvent the structural constraints, perhaps teachers themselves could organise teacher development groups within the workplace to engage in reflective dialogue. I wonder, however, if the promotion of reflective practice could potentially be discouraged by management in some cases.

Thank you very much for your questions and suggestions, and I would welcome an opportunity to work together on something with you in the future.

Ewen