Airi Ota, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan

Ota, A. (2019). Investigating transformation in tutoring sessions. Relay Journal, 2(2), 385-393. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020212

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

The focus of this paper is to investigate the process of becoming an effective student tutor based on perspectives from other student tutors and my own self-reflection, while working at Kanda University of International Studies. The data on which this research is based was from a survey for student tutors registered in the spring semester of 2018. The survey consisted of questions about student tutors’ motivation and approaches to their tutoring sessions, individual interviews with current tutors and weekly written reflections on my own sessions. It discusses challenges that those student tutors faced such as differences in tutoring style, personal English levels, motivation and tutor autonomy. It also explores the reasons why peer tutoring programs are highly beneficial to students. This paper also offers suggestions for future student tutors and tutees as well as for school administrators.

Peer supported learning has been studied by many researchers and the benefits are well documented: improving relationship building skills, self-esteem, social competence and psychological well-being (Briggs, 2013). However, there has only been limited research analyzing how student tutors and tutees have changed over the course of their sessions and created a deep positive learning relationship. When I first became a student tutor, instructors who were in charge of this tutoring program shared a lot of information with us, such as sample questions to ask students and materials to use in sessions. Administrative support given by the instructors was very helpful but it was slightly too general and I struggled with how to improve my sessions. After discussing the situation with professors at my institution, I obtained many useful ideas and significantly improved relationships with my students. This paper discusses my experiences as a peer tutor and the process of how I became a more efficient tutor while investigating how other peer tutors struggled and improved their tutoring skills.

Background

I started working as a peer tutor in May of 2018 at the Academic Success Center (ASC) of Kanda University of International Studies, which provided students with a tutoring program. Its goal was to enhance students’ academic performance, language communication and TOEFL and TOEIC scores (Kodate, 2018). I worked with students both in groups and individually for one semester. Groups were limited to three students and each session was 90 minutes. An individual session took 45 minutes, and appointments were open to anyone. Student tutors taught their tutees TOEFL, TOEIC or Basic English. Tutors were free to decide what content they wanted to cover and tutees also had the freedom to choose their area of focus. Then, the ASC arranged each tutoring group depending on their goals. Any sophomore, junior and senior students who had a certain score (TOEFL ITP 520, TOEIC 800) could be a tutor. I selected TOEFL for my group tutoring sessions and helped students with various topics relative to English learning in individual sessions. I had three freshman students for the group tutoring session. This paper will focus on only my one group tutoring session; however, there are numerous parallels between group and individual tutoring sessions.

Having role models can be a great help for students, but many of them feel a significant distance from their professors because they do not believe they can achieve the same high level of language competency. The effectiveness of peer support in language learning is reinforced by the concept of the Near Peer Role Model (Murphy, 2002). The concept of Near Peer Role Models (NPRMs) is that peers who are similar in many ways, such as age or educational and sociocultural background, can have a huge positive influence on learners. Student tutors possess higher language skills and have experience with different learning strategies. This dynamic relationship can be a great motivator because the competency of tutors can be perceived as more achievable to students than the regular teachers. Positive impacts on Japanese students having NPRMs was proven by an experiment in which the subjects (college students) were shown a short video of Japanese college students making positive comments about learning English: “Making mistakes in English is OK. It is good to have goals in learning English. Speaking English is fun. Japanese can become good speakers of English.” (Murphey & Murakami, 2001). Those watching the video easily identified with the Japanese students studying English in many ways and were able to be encouraged and inspired by them. The author assumes that “seeing NPRMs actually say it in English and enjoying themselves probably gave them more ‘permission’ to actually believe it more” (Murphey & Murakami, 2001). Therefore, in a tutoring context, NPRMs need to focus on being honest and sharing their experiences rather than trying to impress the students with their higher knowledge (Murphey & Arao, 2001).

My tutoring sessions

Peer tutoring requires a lot of problem-solving skills in order to contribute to tutees’ success. Eggers (1995) asserts “peer tutors encounter several areas of difficulty when dealing with the different personalities and problematic issues of the tutees, which requires them to be always alert to provide practical and systematic help to students.” (p.??) Exchanging knowledge with tutees is not the only task peer tutors need to perform; they need to pay attention to various aspects such as tutees’ personalities, motivation or learning style preference, e.g. if they are auditory or visual learners, in order to build a solid relationship. When researching about relationship building in tutor experiences, few journal articles on the topic were discovered. However, it is important to be aware of the characteristics of competent tutors (see Chen and Liu, 2011). In their work, it was revealed that students were more willing to ask their tutors questions and share their stories because they enjoyed these conversations. In order to strengthen the connections, it’s necessary for tutors to create an open dialogue and make an effort to learn more about the students.

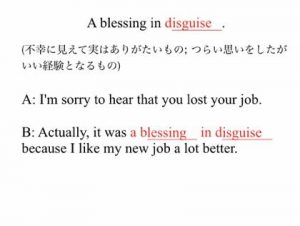

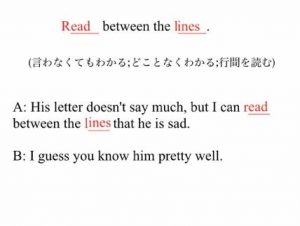

In the first five or ten minutes of my sessions, I always asked students how they were doing in their classes and if they did something fun during the week. Students often shared a lot of struggles that they had in their classes. The most common concern for almost all the freshman students in my group session was that they wanted to improve their speaking skills but didn’t know how to achieve it. While trying to create more opportunities to converse in English with native speakers, they felt overwhelmed by the rapid and energetic style of native speakers’ and couldn’t produce as much as they wanted. I shared some learning strategies that I applied to speaking, for example, having inner conversations in English and writing down every expression that can’t be found in Japanese, speaking English by yourself when alone and writing down what you couldn’t say, jotting down phrases that you might want to use when you are in class listening to the teacher. I also asked them to think about one or two phrases they wanted to know how to say in English so that they could fill their knowledge gap. Once I shared these methods, the amount of questions they asked me dramatically increased. Instead of passively learning English, the students became more proactive and self-directed. Encouraging a heightened curiosity while setting realistic goals were my priorities. Obviously, students wanted to learn phrases that they could actually use in their everyday conversations with teachers and foreign friends. Thus, I incorporated common phrase quizzes, recommended by my teacher, which I included in my sessions. The pictures below illustrate some examples of the common phrase slides that I used. The students reported that these phrases were very beneficial because they were relevant to their daily lives.

Another transformation in my tutoring techniques was tailoring students’ needs to sessions and thus, demonstrating my genuine concern for them. This proved very effective because they realized that my motivation for tutoring was altruistic, not mercenary. Furthermore, I discovered that it might be helpful to give them a survey that would elicit their needs because some students are too shy to speak up about what they want. One question that I asked in the survey: “Do you have anything you would like me to cover in the session in addition to TOEFL preparation?” The reason I asked this question was because I tended to help them with TOEFL reading materials and grammar questions and realized doing these exercises for 90 minutes can be boring and tiring. Witnessing the negative consequences of weariness made me realize how critical it is to stay awake and focused.

The result of the survey revealed that everyone wanted to incorporate something different in the session such as English-speaking practice time, sharing my study abroad experience and reviewing what we learned in the last week. After identifying their needs more clearly, I changed my approach to the time we had together. I controlled the amount of grammar instruction I shared with them because I tended to spend a lot of time teaching details. Instead, I allocated the time for speaking English and asking students questions so that they could have more opportunities to do output. When I chose the materials for the session and asked students some questions, I tried to give them something a little bit challenging in order to maintain their interest in learning and feel a sense of achievement; sometimes, students taught each other. For example, when one student knew the answer and the other did not, I encouraged the informed student to explain to the rest of the students. When students were frustrated by low test scores, I shared that I had experienced similar difficulties. In addition, we discussed how to prepare for studying abroad. Acknowledging the challenges of learning a second language meant they could appreciate what I brought to our sessions. Sharing the challenges of learning a second language helped them to work toward their goals in the long term. Therefore, I attempted to personalize each session while still dedicating time to their goals. While agreeing on a plan for each session, we aimed for balance and productivity without being rigid. Therefore, it became obvious that flexibility is critical because motivation and energy are more important than timelines.

Building trust is another important aspect of peer tutoring because feeling safe is critical for learning. Saunders (1992) argues that peer tutoring could be interpreted as peers who have equal status helping each other. Nonetheless, it tends to be considered as a program where advanced students teach less advanced students. Therefore, some students have the perception that tutors have professional skills (Thonus, 2014); however, it is important to be honest and address that they do not know how to respond when facing some questions they cannot answer. When I was tutoring students, they sometimes asked me very difficult grammar questions. Instead of hiding the fact that I didn’t know, I tried to be upfront and tell them that I would do some research and give them the answer the following week. A Q Desk was also available, a place where students could go to ask professors any questions related to English learning, so I often brought questions I was unable to answer and asked for advice about my tutor sessions as well. As I continued my sessions, I realized that it was more important to secure answers to their queries than to impress them with my own knowledge. However, I realized that I could identify my own methodology but was not certain of other tutors’ perspectives.

Investigation on tutors’ motivation and teaching strategies

To better understand the motivation and teaching strategies of other student tutors, I investigated their ideas by posing seven questions:

- What encouraged you to become a peer tutor?

- Did you share your English learning experience with students? If so, why?

- What efforts, if any, did you make in order to make a positive learning relationship with tutees?

- Did you change your teaching approaches depending on your students’ needs? If so, how?

- What kind of content did you cover in sessions?

- Did you have a short meeting with students about the content and pace of the session? If so, how many times?

- Did you make an effort to improve your skills as a student tutor? If so, how? Did you utilize any academic services at school?

Since I administered the survey under severe time constraints, the data needed to be collected within one month. I was able to collect data from only ten students out of 26. However, the answers were very informative and provided many insights. It turned out that most of the student tutors decided to become tutors for three reasons: to improve their own English skills; interest in collaborative peer learning; or inspired by their tutors from when they were freshmen. Only one person responded that they became a tutor in order to earn money. However, their primary motivation in tutoring was to improve their own English and share their knowledge. Moreover, all ten of the survey respondents indicated that they shared their own personal learning experiences readily. They recognized that their students faced the same challenges that they had encountered before and that sharing their own learning strategies would prove very beneficial. To facilitate a positive learning relationship, most of them talked about their classes and teachers and also used social media. The majority changed their teaching approaches when requested. While only a few tutors actually gave students a survey, many had discussions with their students about how their sessions were going and how they wanted to change. According to the data, 30 percent of tutors had more than four discussions with their tutees. Grammar was the most frequently taught subject. One might assume that both tutors and students tended to think grammar was the easiest section to improve; in addition, grammar was most often considered their highest level of competence. This is because Japanese English education frequently focuses on grammar and was often mentioned as the simple subject to teach. Nonetheless, each tutor had their own unique teaching approach to their sessions. While some tutors allowed students to explain answers, others preferred to retain a leadership role. On the other hand, some student tutors tended to teach by themselves instead of encouraging students to explain grammar points to each other. Therefore, I concluded that student tutors had two types of approaches: one was tutee-led and the other was tutor-led.

Also, I was able to interview one of the tutors who was a senior. One particularly effective activity was that he always gave students a piece of paper at the beginning of each session and asked them what they wanted to achieve that day. If they attained their goals, they could feel a sense of accomplishment. He mentioned his students tended to make big goals at the beginning of the semester, but they gradually started to make more achievable goals, e.g., asking at least three questions, getting higher scores on the vocabulary test or speaking up before the tutor calls on someone. They were able to be more realistic about what they could achieve in a certain time and became more motivated. He also mentioned that he tried to give students a lot of compliments in order to heighten their motivation and curiosity.

Another interesting result from the survey is that where the student tutors received support. A large number of student tutors get help at the meetings frequently done by the ASC (100%) and also asked other tutors for advice (80%). Only 30 % of them used the Q Desk at ASC where they could discuss their sessions with Japanese professors and ask them any English questions; they also utilized KUIS8 where they can speak English with both native speakers and Japanese teachers who assist students with their English learning strategies (they try to find the most effective way for each student to improve their English skills). One student mentioned seeking assistance from a friend who was good at English grammar.

Suggestions

It is obvious that not many student tutors made the most of the services available to them. It might be beneficial if they have chances to discuss their sessions with professors, who have more experiences with teaching English, in order to get new perspectives. Moreover, the ASC is known as a place where students can ask English questions (a place where students learn grammar) in Japanese, especially grammar, and Kanda’s Self-Access Learning Center, also known as KUIS 8, is known as a place where students should practice speaking English. Thus, many students go to KUIS 8 to have everyday conversation practice such as discussing their weekend activities, hobbies and food. Interestingly, a large number of teachers at KUIS 8 frequently research English teaching and some of them tutor students one on one for 15-30 minutes. Therefore, it might prove useful for student tutors to talk with them about English teaching and strengthening their understanding towards teaching English. In this way, English Language Institute (ELI) teachers can share their knowledge with student tutors. Furthermore, collaboration between the ASC and KUIS 8 could result in benefits for students. For example, some ELI teachers could lead workshops about collaborative learning for student tutors or create some opportunities to share their knowledge.

Conclusion

Earning trust and being curious seem to be the most essential elements of successful tutoring sessions. If their Near Peer Role Models are curious and eager to improve their English skills, students are more likely to be affected positively. In addition, helping students develop the art of being inquisitive plays an important role in all learning environments. According to Gino (2018), curiosity promotes more respect for tutors and encourages groups to develop more trusting and collaborative relationships. If students become more curious, they will ask more questions which facilitates more open conversation. While this paper has focused primarily on student tutors’ perspectives, looking at tutees’ and administrators’ points of view would bring further understanding of this topic.

Note on the contributor

Airi Ota is a former undergraduate student at Kanda University of International Studies. She majored in English at the university and studied hospitality, American history and gender equality at Whatcom Community College in the United States. Her research interests include advising in language learning, learner motivation and learner language learner identity.

References

Briggs, S. (2013, June 7). How peer teaching improves student learning and 10 ways to encourage it. Retrieved from https://www.opencolleges.edu.au/informed/features/peer-teaching/

Ching, C., Chang-Chen, L. (2011). A case study of peer tutoring program in higher education. Research in Higher Educational Journal, 11. Retrieved from link

Eggers, J. E. (1995). Pause, prompt ad praise: Cross-age tutoring. Teaching Children Mathematics, 4(2), 216-220.

(Interview with student tutors, 2018) in the paper

Kodate, A. (2018). Reconstructing a peer tutorial programme: Towards cooperative, deep learning in Japanese tertiary education. The Journal of Kanda University of International Studies, 30, 415-434.

Murphey, T., & Arao, H. (2001). Reported belief changes through near peer role modeling. The Electronic Journal for English as Second Language, 5(3), 1-15.

Murphey, T., & Murakami, K. (2001). Identifying and “identifying with” effective beliefs and behaviors. NLP World, 8(3), 41-56.

Saunders, D. (1992). Peer tutoring in higher education. Studies in Higher Education,17(2), 211-219.

(Surveys from student tutors and tutees, 2018)

Thounus, T. (2014). What are the difference? Tutor interactions with first- and second-language writers. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13, 227-242.

Dear Airi,

I was quite delighted to read about the ‘Investigating transformation in tutoring sessions’ column! Your case study is definitely a good idea to stress the importance of self-reflection among tutors/advisers, not only among tutees. Moreover, you focus on peer tutoring in higher education – a topic that is still quite crucial in times of changing (language) learning environments (for futher reading, see also Falchikov, Nancy (2001). Learning Together. Peer tutoring in higher education. London: Routledge).

Your paper will offer an opportunity for advisers to cultivate and initiate a curiosity about the advisers’ professional experience and to reflect on their dual roles as researchers and practitioners.

You mentioned the importance of being an effective tutor/advisor. I am interested in getting to know how you measure ‘effectivity’. Could you may be elaborate a little bit more on that? When you write about your program, you said that advanced students teach less advanced students. Is it really teaching or more advising? Peer tutoring or peer-supported learned generally is non-directive and more a co-construction of learning. What about the idea to support them with strategies to find the solution themselves instead of giving them precise answers? This could be an aspect for further research.

As I have been coordinating a tutoring program to foster autonomous language learning for more than 10 years, I am very much into accompanying scientific research on a possible benefit of counseling sessions for tutors and tutees. You have mentioned a survey for student tutors. What kind of methodological framework have you applied?

In your tutoring, you are covering a range of goals from academic language performance in general to the preparation for certain standardized language tests. You mentioned that tutors were free to decide what content they wanted to cover. Does the content depend on the tutee’s actual needs or is there a kind of curriculum for the tutoring sessions?

I am quite curious to get to know, if you have any backup from literature or from your own research for your hypothesis that having role models can be a great help for students. What kind of role models are you thinking of?

You stress the aspect that it seems to be quite important to establish common ground in the advisory sessions. I totally agree – apart from discourse strategies, affective factors are quite crucial in building trust. (for further reading, see also Buschmann-Göbels, Astrid /Bornickel, Marie-Christin / Nijnikova, Marina (2015): „Meet the Needs – Lernberatung und tutorielle Lernbegleitung heterogener Lerngruppen zwischen individuellen Bedürfnissen und fachlichen Anforderungen“, in: ZiF 20 (1). (in German); Tassinari, Maria Giovanna (2016). Emotions and feelings in language advising discourse. In C. Gkonou, D. Tatzl, & S. Mercer (Eds.), New Directions in Language Learning Psychology (pp.71-96). Springer.

When you give the example of the “phrases” (collocations, etc) to show the importance of setting realistic learning goals, it adds to the idea of using learner-centered approaches and authentic material in language counseling.

In your suggestions, you stated that it is “obvious that not many student tutors made the most of the services available to them”. We made similar observations in our tutoring program a couple of years ago and started to design offers like regular workshops on learning strategies for autonomous language learning (e.g. How to set reasonable learning objectives? How to reflect my own learning process and give feedback to others? How to select reasonable learning material? – just to mention a few) to support autonomous learners and to retain their initial motivation.

In your paper, you are trying to get insights into three separate things: (1) What makes tutors adapt their advisory techniques to their tutees to be “effective”, (2) what motivations do tutors have to become a tutor? And (3) in how far is the tutor developing his/her skills over time and which aspects contribute to this professional development. I definitely agree that these are crucial questions, every language advisor should have in mind and should generally reflect on – with the tutors as well as with oneself and with other advisors.

Please forgive all of my questions – your article was quite inspiring and I would enjoy to read more about your coming projects.

Thank you very much for your feedback.

I am very appreciative of you providing me with a lot of reading materials related to peer tutoring, advisory sessions and language learning psychology. I will utilize the readings that you shared with me when writing a paper next time. Also, your observations regarding your own tutoring programs and questions made me think about my tutoring experience on a deeper level.

———————————————————————————-

(Airi’s answers to Astrid’s questions)

I revised my paper based on your feedback. However, I would like to answer your questions in this comment as well. I believe you asked me mainly six questions.

1. How do I measure effectiveness of student tutors?

There are several characteristics that I think effective tutors have (please look at the list below).

-Earns trust

-Is honest even when not knowing an answer

-Creates an open dialog

-Makes an effort to learn more about students

-Helps them with making realistic plans to improve their English skills

-Tailors students’ needs to their sessions

-Gives them some challenging tasks to keep their motivation high

-Shares their English learning experiences and is empathetic

-Lets them teach each other

2. When you write about your program, you said that advanced students teach less advanced students (para9, line 4). Is it really teaching or more advising?

I actually wrote this sentence not to explain my sessions but to explain that this is what most people think about tutoring. After this sentence, I mentioned it’s important for student tutors to be honest and admit when they encounter some difficult questions even if their students expect tutors to know everything (←This is what a lot of people think; tutors know everything). Also, I do feel like my tutoring experience was similar to advising. This is because when you explain something to a student, you often give advice on how to solve problems or improve skills. My students and I often tried to discover the most useful ways to improve their English skills by implementing a lot of learning strategies in the session.

3. Does the content depend on the tutee’s actual needs or is there a kind of curriculum for the tutoring sessions?

There were three categories to choose from (TOEFL, TOEIC, and Basic English). However, student tutors were able to be creative and flexible with their teaching approaches in order to meet their students’ needs.

4. What kind of methodological framework have you applied?

I used Google to create the survey. The survey had 10 questions, half of them were multiple questions and the other half were essay-type questions. It takes roughly five minutes to answer all the questions. As for the essay-type questions, they could write as long as they wanted. However, most of them wrote two or three sentences. Those questions were focused on their teaching approaches and how their motivation affected their sessions and how they build relationships with their students.

5. Do I have backup from literature or from my own research for my hypothesis that having role models can be a great help for students?

My hypothesis that having role models can be a great help for students is supported by the paper written by Tim Murphey. He talks about how peers who have similar background have a huge impact on students and the importance of peer tutoring, because a lot of students feel distance from their teachers and don’t feel as motivated as they are when speaking to someone who is at a similar level of proficiency.

6. What kind of role models am I thinking of?

Peers who have similar backgrounds but they have slightly higher knowledge or more experiences than the students. Also, the characteristics of effective tutors are somewhat parallel with the characteristics of role models. Having empathy and building solid relationships are always important for peer tutors. For example, most freshman students haven’t studied abroad. However, they feel intimidated or overwhelmed when speaking with native speakers because they feel intimidated by their lack of language skills. However, if they can practice speaking with their peers, they feel like the achievements made by their peers are not too high and therefore, they are able to make realistic goals which make them feel more motivated.