Aya Hayasaki, Waseda University

Hayasaki, A. (2023). When does English become “My” language? Japanese EFL students’

(trans)forming perceptions of English ownership. Relay Journal, 6(2), 105-122. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/060202

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

Although much of the world’s English-speaking population is made up of so-called non-native speakers, many learners of English as a foreign language (EFL), particularly those from Japan, nevertheless consider their variety of English in a negative light and believe that English does not belong to them. However, little academic discussion has occurred regarding the process through which such learners develop their perceptions about English. This study qualitatively investigated how individual learners transform their attitudes concerning English language ownership over time and across contexts. One Japanese male university student and one Japanese female junior college student participated in a semi-structured interview, and data were analysed through the lens of language ownership. The findings revealed that learning English in an Inner Circle context did not necessarily provide EFL learners with a greater sense of ownership of English, nor did living in an Expanding Circle context necessarily restrict it. This study highlights the importance of accepting different varieties of English as legitimate and encouraging learners to embrace their own language variety in order to increase their confidence in using English. Overall, this study contributes to a better understanding of the complex relationship between language ownership and language learning in EFL contexts.

Keywords: language ownership, native-speakerism, learning beyond the classroom, study abroad

“English is used all over the world, but it does not belong to the world” (Matsuda, 2003, p. 493)—maybe English did not belong to the world before, but is this still true today? And if this is what many people believe, how might this inform language learning and teaching? It is widely known that non-native speakers of English now constitute the majority of the world’s English-speaking population (Crystal, 2012). According to previous research, however, English learners in the “Expanding Circle” (Kachru, 1985), which includes Japan, continue to view English as a language primarily belonging to native speakers or those in “Inner Circle” countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, as seen in the quote above by Matsuda and in many other studies (Saito, 2012; Saito & Hatoss, 2011). This resonates with my personal experience as a Japanese who learned English as a foreign language. Having taught English lessons at a Japanese public senior high school in the late 2010s and currently at a Japanese university, I have also observed similar attitudes among my students toward the ownership of English. This tendency may stem from a lack of exposure to English in natural settings and the prevalence of native-speakerist discourse in the media and educational institutions (Houghton & Rivers, 2013).

However, little academic work has examined how individual learners can transform their attitudes and ideas about the English language across the various contexts they encounter and over extended time (Saeki, 2015). Would their perceptions of English change if they had more exposure to English, and to what extent would the variety of English and the kind of context matter? Furthermore, individual differences and diversity among learners may have been overlooked in previous research. To address these gaps, this study was aimed at gaining a qualitative understanding of the contexts in which individual learners are situated and their changes over time. Retrospective interviews were conducted with two learners who graduated from the same high school but followed divergent trajectories thereafter. Through the lens of language ownership, the learners’ narratives were analysed to explore the formation of their sense of English ownership. By illuminating the changing perceptions of English ownership among learners of English as a foreign language, I hope that this study contributes to a better understanding of the sociocultural and dynamic nature of World Englishes.

Literature Review

Before reviewing studies related to language ownership, it should be noted that there are potential problems with categorising language speakers as “native” or “non-native” and that there has been a reconsideration of the use of these terms, particularly in research on multilingualism. As a matter of course in the world of foreign language teaching, Firth and Wagner (1997) argue that the linguistic and non-linguistic behaviour of “native speakers” (NS) has been seen as “standard” and that of “non-native speakers” (NNS) as “deviant”; the authors claim that speaking like a “native speaker” has often been the goal for language learners. Holliday (2006) criticises the term “non-native speaker” as problematic in itself. Holliday argues that native-speakerism categorises teachers according to a “us–them” ideology, a discriminatory stereotype of superior NS versus inferior NNS, placing NS teachers in a privileged and dominant position. Holliday further argues that not only students but also teachers should abandon discriminatory attitudes and take the position that all those involved in English language teaching are “we.” In this vein, Cook (2002) proposed the label of “L2 users” as an alternative to “non-native speakers,” suggesting that those who use a second language (L2) in addition to their first language (L1) in real life should be called L2 users. Despite the above discussions, it was necessary to use these terms in this paper; the reason was not only for convenience but also because such categorisation stems from the Japanese context in which the research participants of this paper were situated, as explained below.

Perceptions of English in Japan

Much research has been done on the sociolinguistic role of English in the Japanese context. Matsuda’s (2003) interviews and Saito and Hatoss’s (2011) large-scale questionnaires investigating Japanese high school students’ perceptions of English show that although the students had abstract knowledge of the concept of English as an international language, on a personal level, they believed that English actually belonged to speakers in Inner Circle countries. Matsuda’s respondents showed awareness of speakers in the Outer Circle, such as Singapore and India. However, Matsuda reported, “Even though most students only knew about differences and claimed that they could not actually identify them, they often expressed preferences for one variety over others” (p. 489). Matsuda also asked the participants about their perceptions of Japanese English. She found that they thought that English loanwords and Japanese English words were acceptable on an abstract level, but not at a personal level. As Honna (1995) wrote:

Japanese students of English not only cannot accept their limited proficiency as natural and inevitable, but also look down on non-native varieties of English used by Asian and African speakers [and] hesitate to interact with English speakers “until,” as they are often heard to say, “they develop complete proficiency in the language” (p. 58).

Matsuda (2003) proposes several strategies to promote awareness of English as an international language (EIL), including: 1) expanding exposure to diverse varieties of English, 2) facilitating opportunities for intercultural communication with individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds, particularly those other than American or European ones, and 3) accurately assessing students’ communicative competence to bridge the gap between the national educational goals that prioritize this competence and classroom practices that emphasize grammatical competence and receptive skills. As Matsuda suggests, “the shift in English education from learning and aspiring [to] ‘native’ English speaking cultures to focusing on the international and pluralistic aspects of English is beneficial and necessary for learners of English as an international language.” (p. 495)

However, based on my personal observation after more than two decades since Matsuda’s study above, a lot of Japanese learners of English today still seem to set their goal of learning as “to become able to communicate with native English speakers smoothly” (quoted from one of my current students’ responses to a classroom questionnaire). Furthermore, while previous studies including Matsuda (2003) and Saito and Hatoss (2011) contributed valuable insights into the high school and university contexts, respectively, the dynamic nature of beliefs and identities (Thomas & Schwarzbaum, 2017) are not taken into account by these authors. To better understand how students’ perceptions about English form and potentially transform, in this paper, I decided to incorporate the concept of language ownership, which was used by Seilhamer (2015) to investigate the ownership of English in Taiwan, as an analytical framework. In the following sections, I will introduce the conceptualisation of language ownership and examples that show how the concept has developed from research on the Outer Circle (Singapore) to the Expanding Circle (Taiwan).

The conceptualisation of language ownership

In the conceptualisation of language ownership, the essentialist belief referred to as the “birthright paradigm” (Parmegiani, 2008, 2010), which portrays linguistic ownership as determined by the ethnicity of one’s parents or place of birth, still dominates. However, this belief is problematic, as it fails to account for the dynamic and continuously constructed nature of identity (Thomas & Schwarzbaum, 2017). Scholars in linguistics have long insisted that those who are learning a language can rightfully claim ownership of it. In this vein, Halliday et al. (1964) noted that English is an international language, used by an increasing number of people for various purposes. Nelson (1992) further suggested that each user of English can claim ownership of it and adapt it to appropriate contexts in their or another’s culture. While some may find this perspective radical, Saraceni (2010) argued that individuals who think in this way do not require authorisation from professional linguists, and such approval may not in fact be significant. However, the reality is that a majority of English learners and users continue to subscribe to the birthright paradigm, as seen in Taiwan (Ke, 2010), Greece (Sifakis & Sougari, 2005), and former British colonies, such as Malaysia (Pillai, 2008; Saraceni, 2010).

Becoming owners of English

According to Park’s (2011, as cited in Seilhamer, 2015) study of English ownership among Singaporeans, there is social pressure to consider English a language of the West, but English may be increasingly accepted as a local language in Singapore. Based on Park’s insights, Seilhamer (2015) developed a theoretical framework for the examination of language ownership including three dimensions: prevalent usage of the language, affective belonging to the language, and legitimate knowledge of the language. These dimensions contribute to individuals’ understanding of their language ownership and can be applied to the study of language ownership in various settings. The definitions of each term here are derived from Seilhamer.

First, prevalent usage refers to the frequency and extent of language use, encompassing virtual interactions such as email correspondence, blog posts, phone conversations, and other forms of online communication, in addition to face-to-face communication. Both spoken and written language skills are relevant here, including both productive and receptive competencies, which can be enhanced through exposure to different literary genres, technical reports, and films, among other sources, contributing to a sense of ownership.

The second dimension, affective belonging, refers to the emotional connection with a language. It is in alignment with Rampton’s (1990) notion of language allegiance, referring to one’s feelings toward the social or ethnic group associated with a particular language to establish a sense of language ownership. Typically, emotional attachment to a language originates in acquiring it during one’s upbringing or as an inherited language. Nonetheless, it is not necessary for this in that the language be spoken since infancy; as Rampton posits, the bond between romantic partners may be more potent than that between parents and children. An emotionally based connection may be more important than one based on biological relation or ethnicity.

Finally, legitimate knowledge encompasses Rampton’s (1990) idea of language expertise but extends beyond proficiency to encompass the subjective evaluation of one’s language use. As Seilhamer (2015) argues, “even if one’s English, by any criteria, is nothing short of exquisite, this exquisite usage may not be regarded as legitimate by the speaker … based purely on the speaker’s ethnicity or origins” (p. 376). This view is consistent with Bourdieu’s (1977) conception that a learner’s relationship with a language affects their sense of legitimacy or “right to speak.” Norton (1997) similarly emphasizes the importance of the connection between legitimacy and the learner’s relationship with the language. Following Norton, Higgins (2003) compared dyads from Singapore, Malaysia, India, and the US in acceptability judgments and found that “speakers from the outer circle displayed less certainty, or lesser degree of ownership, than did the speakers from the inner circle” (p. 640). Ryan (2006) suggests that “what compels many English learners in Expanding Circle contexts to dedicate considerable time and effort to English study is, in fact, a sense of membership in an imagined global community of English users” (p. 375).

These dimensions of language ownership can be observed at both macro and micro levels, with societal-level ownership being more linked to lived experience. Seilhamer (2015) reports examples of micro-level ownership in his in-depth interviews with Taiwanese university students on their sense of ownership of English. Students’ narratives about their lived experience revealed how they developed or did not develop degrees of ownership as L2 English learners or users in EFL contexts. Here, he justifies the reason of using the term “degree of ownership” as follows:

While individual requirements for full membership in the imagined global community of English users would surely be less stringent than for English ownership (hence, representing a degree of ownership), the same dimensions would nevertheless apply, as both are psychological stances that locate, in varying degrees, ‘the English language within one’s own Self’ (Saraceni, 2010, p. 21) rather than entirely within the Other. (Seilhamer, 2015, p. 375)

As Seilhamer’s research on English ownership in an Expanding Circle country aligns with the objectives of the present study, his methodology was adopted for use in the context of Japan.

Additionally, while the concept of English ownership has been introduced to better understand the perceptions of English in learners from the Expanding Circle countries, few qualitative studies particularly on the Japanese context have adopted this as an analytical framework. To fill this gap, this study addresses how participants’ conceptualization of English ownership evolves from their high school contexts to their current use of EIL.

Specifically, this study addresses the following two research questions:

- What conceptualizations of English ownership do two Japanese university students studying in Canada and Japan exhibit?

- What factors most strongly influence the development of these students’ English ownership in their different contexts?

Methodology

The present research employed a qualitative and interpretive approach to investigate variations in individuals’ perceptions of English ownership. Specifically, in this study I sought to provide a thick description (Geertz, 1973) of the participants’ ideological beliefs about English ownership and examine how contextual and social factors have influenced their present beliefs in light of their experiences with EIL. Although the term “EIL” is defined differently by different scholars, it is used here to refer to language as a medium of communication between people who speak different languages, consistent with the definitions provided by Matsuda (2003) and Seilhamer (2015).

Participants and context

Six Japanese students (five in university and one in junior college) were interviewed for approximately 60 minutes on average, with a few extended to about 90 minutes. Two were selected for further analysis. These two participants were chosen due to the different characteristics of their backgrounds and their ability to provide diverse perspectives on the research questions. In terms of gender, from the three male and three female students initially interviewed, one participant of each gender was selected. Both were 20-year-old Japanese nationals who grew up in small cities in southern Japan. They were educated in public schools from elementary to high school and spoke Japanese as their first language. English was introduced to them as a school subject at the age of 13. When I interviewed them, one was attending a 4-year university, and the other a 2-year junior college in different parts of Japan.

The researcher’s positionality

I was the English teacher for all six students from 2014 to 2016, providing English lessons for 5 days per week for 2 years in their second and third years of senior high school. These six students had different personality traits, interests, and levels of motivation with respect to learning English. We continued to keep in contact after their graduation. To ensure the suitability of this group as participants in this study, I used purposive sampling. Because this study investigated the participants’ educational trajectories to identify their underlying ideologies, it was important that the investigator have a comfortable relationship with the participants. This relationship allowed the participants to openly discuss their personal experiences in relation to English learning and use, which could potentially involve sensitive emotions. As their former teacher, I had some pre-existing ideas about their personalities, behaviour, and interests. While being conscious of the possibility that such prior knowledge could interfere with my research and judgment, I tried to take advantage of my personal relationship with them to understand their characteristics and to delve into more notable aspects of each individual.

Data collection and analysis

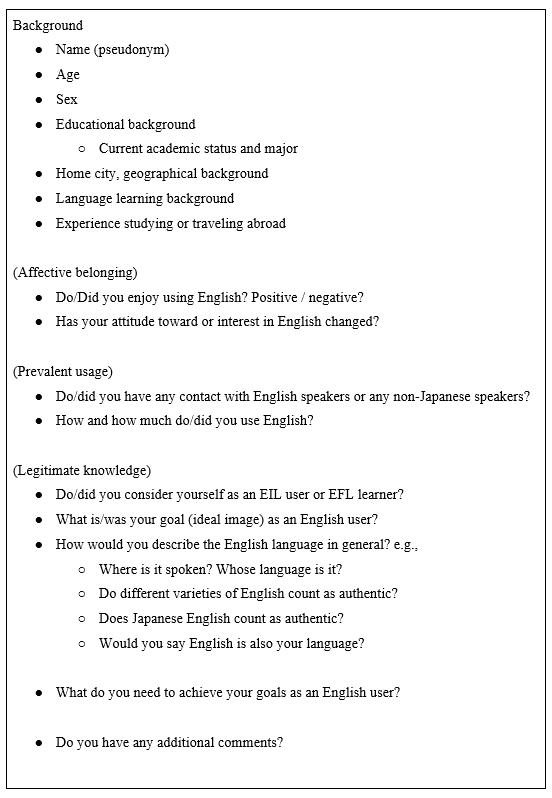

Semi-structured interviews were conducted through online voice calls via Facebook Messenger or the messaging application LINE. These applications were chosen due to their flexibility, allowing for the reordering of questions, the posing of follow-up questions, and the emergence of unexpected themes. Before conducting the interviews, I prepared broad-based questions based on an extensive literature review that would provide an in-depth understanding of the participants’ perceptions and experiences regarding their ownership of English. The interviews began with small talk on their post-high-school experiences before moving on to their educational and language-learning backgrounds, language practice habits, and self-perceptions as English learners or users in their current context. The interview questions are provided in Appendix 1. Participants were informed of the purpose of the study and were assured of their anonymity and right to withdraw at any time, for any reason, and without negative consequences for them. The theoretical framework employed in this study was based on Seilhamer’s (2015) adaptation of Park’s (2011, as cited in Seilhamer, 2015) three dimensions of language ownership: prevalent usage, effective belonging, and legitimate knowledge (see Figure 1; see also literature review in this article).

Figure 1. Seilhamer’s (2015) Three Dimensions of Language Ownership

To ensure the validity of the data, during the interview, I rephrased or summarized the participants’ responses to check my understanding of key points. To ensure that my questions were clearly worded, I tried to make the conversation flow as naturally as possible. All interviews were conducted in Japanese and later translated into English by myself with the help of DeepL, an AI translation machine.

Findings and Discussion

This section explores changes in the degree of English ownership in two Japanese students, Saki and Kenji (pseudonyms).

Saki’s experience in Canada

Saki, a diligent but reserved student, made significant progress in her speaking abilities during a 10-month stay in Canada in her second year of junior college. She began to view herself more as an English user than a learner. However, she still felt nervous when speaking with a “native” English speaker due to inaccuracies in grammar and pronunciation. Her preference for a native-speaker norm rather than EIL was salient; this seemed to have been constructed through not only her own experience learning English as a subject in Japanese school and university curricula but also through interactions with her native-speaker teachers and her host family in Canada. She consistently viewed native speakers as the ideal or complete model, in contrast with speakers of non-native varieties of English, including herself, which she perceived as incomplete.

As for prevalent usage, Saki seemed to have the most exposure to English among the original six participants in my interviews. She had spent the previous 10 months in Canada attending ESL classes and had just returned to Japan a month before the interview. While in Canada, she had daily interactions with both local and international friends. Even after she returned to Japan, she continued to communicate with her Canadian host family. As an English language major, she attended many language classes that included conversation with “native English speaker teachers” at her university in Japan.

With regard to affective belonging, Saki had always been keen to improve her English. In high school, she enjoyed studying English and had once wanted to become a professional translator. She maintained a good relationship with her host family in Canada but still got nervous and made English mistakes when speaking to her host mother, who was an English teacher. In particular, she said that she needed to practice speaking to reduce her level of nervousness, especially with native speakers, to assert her English ownership with confidence.

In terms of legitimate knowledge, Saki described English as “an international language everyone understands,” but she believed that the language truly belongs to “native speakers like British, Canadians, Australians and Americans,” saying that “everyone can use it, but those who have their own first language can use it as their second language.” This aligns with the “native-speakerism” perspective noted by Honna (1995) among Japanese English learners. In relation to this, Saki showed a clear aversion to a Japanese accent in English, as evident in the following excerpt:

Saki (S): When I hear a Japanese person speaking English, even if I don’t know them, I can often tell from their accent that they are Japanese. I want to be able to speak correctly enough for strangers not to notice that I am Japanese.

Author (A): Do you have any negative feelings about sounding Japanese?

S: Yes.

A: Was there an event that made you feel this way?

S: I have always felt that way. When I speak a language, I want to speak it perfectly… But in Vancouver, there are people from different countries, and they speak with their own accents, like Chinese. Nobody cares about pronunciation and things like that, they’re like, it’s OK as long as you can make yourself understood. So, I would say pronunciation is important, but your willingness to communicate is also important. I kind of feel like people don’t care that much about my pronunciation, but it’s me that cares.

She also stated that she had always been good at reading and listening but not speaking; however, as speaking activities were rarely assessed in her classes, she was confident in her abilities in English as a school subject. However, after matriculating in the English department of her college, she found it difficult to maintain her confidence in many conversation-driven English classes conducted by teachers from Inner Circle countries. Saki continued:

If the person is non-native, not having native-like accents might not bother me as much. But when I talk to native speakers, even a slight difference in my pronunciation makes them go like, “Hm?”, and I kind of feel upset at myself to think that if my pronunciation was better, my meaning would have been understood.

Another influential factor in Saki’s adherence to native-speaker norms appeared to be her host mother, who worked as an English teacher and would regularly correct Saki’s pronunciation. Although this sometimes bothered her, Saki recognized the authority of her host mother and acknowledged the value of learning from her corrections, saying, “But she is the one who is right, so it cannot be helped and I learn from it too, of course.”

During her 10 months in Vancouver, Saki’s native-speaker norm remained strong. However, her exposure to people from diverse cultural backgrounds also made her aware of the general acceptability of varieties of English and the significance of communicative competences. This includes the importance of meaning, in addition to form, for effective communication:

When I talk to my classmates, their English is at about the same level as mine. I can say things in my own words without worrying too much about making mistakes. But when I talk to native speakers, I feel like they are perfect users of the language, with naturally perfect pronunciation and grammar. That’s why I get so nervous.

Further conversation with Saki revealed that she decided not to study in Australia, which was another option for her study abroad, “because I heard Australian English has a very strong accent.” She continued to describe her preference of Canadian English over others: “After I came back, I talked to a British English teacher, and I can indeed feel the difference. British English might be the authentic one, but I think Canadian English is clearer.” This was quite surprising, as it contradicted her concept of English as the language of Inner Circle countries, including the UK and Australia.

Saki’s perspective on the ownership of the English language seemed to have been largely shaped by the native-speaker norm and possibly reflected a similar concept to Parmegiani’s (2008, 2010) idea of birthright norm. Despite her facility in English and affective belonging to it, Saki perceived herself as only a borrower of the language. Saki’s view seemed to have been influenced by her perceived lack of language proficiency, which affected her confidence in speaking to native speakers. However, it was not clear that achieving perfect pronunciation and grammar would give her a sense of legitimacy. While exposure to different varieties of English through interaction with other non-native speakers influenced her awareness somewhat, it did not significantly alter her ideal conception of an English speaker, which continued to be based on the native-speaker norm.

Kenji’s experience

Kenji was majoring in electronic engineering at a public university in central Japan. He had an open-minded and friendly character. From my observation during his time in high school, he did not show any particular interest in English. However, since entering university, he became involved with a social group of young people who are interested in traveling both in and outside of Japan, which made him come to positively consider himself as a potential owner of EIL.

With regard to prevalent usage, although he had no experience going abroad at the time of the interview, Kenji was taking general English classes at university and had the chance to interact with tourists from other countries while backpacking in Japan.

As for affective belonging, Kenji was inspired and motivated by his interactions with other young people, both Japanese and travellers from abroad, who utilised EIL. Although he had few opportunities to use the language himself, he expressed a strong desire to improve his English proficiency to communicate with people from diverse backgrounds. Contrary to his lack of interest in English during high school, he showed a notable shift in his motivation to learn the language as he had become exposed to different cultures and communities through travel and social interactions:

When I first started learning English, I thought, “I’m going to learn a foreign language” … I didn’t have any particular feeling, I just wondered why I had to learn English. Then, when I went to high school, I started studying English for the entrance exams. Now that I am at university, [I realize that] English is something that is common internationally, and whether you can speak it or not, well, makes a big difference. I would say my view of English has broadened. When I was in junior high school, it was something abstract. But after some new experiences as a university student, I have a clearer idea of what I need English for… Whether you can speak English or not is so important if you want to travel or study abroad and need to communicate with people.

Kenji’s attitude and motivation for learning and using English indicate a possible development in his conceptualization of ownership of English. Although this development may have primarily stemmed from his motivation, his words suggest that he had also developed a vision of himself as a member of an imagined English-speaking community, even though he continued to reside in Japan, an Expanding Circle country.

In terms of legitimate knowledge, Kenji acknowledged that his beliefs about English ownership had changed since he began studying the language 7 years ago, as illustrated in the following excerpt:

Author (A): Who do you think English belongs to?

Kenji (K): When I was in junior high school, I would have answered America, but now I realize it’s not only America. It can be used everywhere.

A: What do you think about people with different accents in English?

K: I think it is OK as long as it can be understood. I know someone from university who is traveling around the world. I have seen in his video posts on social networking services that he speaks English in strong Japanese accent, but he seems to communicate with local people with no problem. It looks like a lot of fun.

During our extended conversation, Kenji highlighted the importance of being exposed to English in real-life situations rather than just in the classroom. This exposure, he explained, allowed him to understand the practical application and value of the language beyond learning it for academic purposes. Through his experiences meeting tourists from abroad and interacting with his friends who used English for communication, he came to recognize a wider range of English speakers, including Japanese speakers of English, as legitimate users of the language. This formed a significant change from his earlier perceptions of English ownership when he first started began English:

We had an assistant language teacher (ALT) at school, but I didn’t feel like talking to her. I didn’t really have a chance to meet anybody from abroad, so when I tried to talk [to people from other countries in an international flat where his friend lived] I was like, “Aaaaagh!” like that. (laughs) I don’t know if this is making any sense, but I was shocked in a good way.

Individual differences in personality and context are certainly important factors, but the comparison between Saki and Kenji is nevertheless intriguing in its broad strokes, as it illustrates that living in an Inner Circle context does not necessarily confer a greater sense of ownership of English, nor does living in an Expanding Circle context necessarily limit opportunities for developing a sense of ownership of the language.

Pedagogical Implications and Conclusion

This study explored two university students’ experiences in relation to their ownership of English. It is important for language learners and users to recognize that non-native speakers are not inferior (Firth & Wagner, 1997), and feeling a sense of ownership over a language can be empowering for learners and users of that language (Seilhamer, 2015). As Seilhamer (2015) argues,

When you are renting a house, you feel as though you must take great care to keep the property intact, for even miniscule thumb-tack holes in the walls might well incur the wrath of the landlord. Things are completely different though when you own the house, for ownership gives you the right to paint the house pink, build trap doors, or do any crazy thing you care to do with it. Similarly, with linguistic ownership, speakers have carte blanche to manipulate the language in whatever way they see fit to suit their own whims and purposes. (p. 385)

In this study, data was not collected on the precise ways in which the participants used English in their given social contexts. Instead, their perceptions of English ownership and legitimacy as Japanese people were analysed, as well as their evolving experiences as English learners and users. The purpose here was to inform language teaching practices by promoting awareness of EIL and empowering English speakers and learners from various backgrounds, including those in Expanding Circle contexts, to feel confident using their own varieties of English. Future research in the form of longitudinal studies or discourse analysis should explore how English ownership develops in actual language use.

Notes on the contributor

Aya Hayasaki is a research associate and Ph.D. student at Waseda University in Tokyo, Japan. She is also a part-time lecturer at Gakushuin University. Her research interests include L2 learner and teacher well-being, learning beyond the classroom, and transformative learning, especially in rural contexts. She holds a Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Foreign Language from the University of Birmingham, UK.

References

Bourdieu, P. (1977). The economics of linguistic exchanges. Social Science Information, 16(6), 645–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847701600601

Cook, V. (2002). Background to the L2 user. In V. Cook (Ed.), Portraits of the L2 user (pp. 1–31). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853595851-003

Crystal, D. (2012). English as a global language. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139196970

Firth, A., & Wagner, J. (1997). On discourse, communication, and (some) fundamental concepts in SLA research. The Modern Language Journal, 81(3), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1997.tb05480.x

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. Basic Books.

Halliday, M. A. K., McIntosh, A., & Strevens, P. (1964). The linguistic sciences and language teaching. Longmans.

Higgins, C. (2003). “Ownership” of English in the Outer Circle: An alternative to the NS–NNS dichotomy. TESOL Quarterly, 37(4), 615–644. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588215

Holliday, A. (2006). Native-speakerism. ELT Journal, 60(4), 385–387. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccl030

Honna, N. (1995). English in Japanese society: Language within language. Journal of Multilingual & Multicultural Development, 16(1-2), 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.1995.9994592

Houghton, S. A., & Rivers, D. J. (Eds.). (2013). Native-speakerism in Japan: Intergroup dynamics in foreign language education. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847698704

Kachru, B. B. (1985). Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: The English language in the outer circle. In R. Quirk & H. G. Widdowson (Eds.), English in the world: Teaching and learning the language and literatures (pp. 11–30). Cambridge University Press.

Ke, I. (2010). Global English and world culture: A study of Taiwanese university students’ worldviews and conceptions of English. Journal of English as an International Language, 5, 81–100.

Matsuda, A. (2003). The ownership of English in Japanese secondary schools. World Englishes, 22(4), 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971x.2003.00314.x

Nelson, C. (1992). My language, your culture: Whose communicative competence? In B. B. Kachru (Ed.), The other tongue: English across cultures (pp. 327–339). University of Illinois Press.

Norton, B. (1997). Language, identity, and the ownership of English. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 409–429. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587831

Parmegiani, A. (2008). Language ownership in multilingual settings: Exploring attitudes among students entering the University of KwaZulu-Natal through the access program. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, 38(1), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.5774/38-0-24

Parmegiani, A. (2010). Reconceptualizing language ownership. A case study of language practices and attitudes among students at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. Language Learning Journal, 38(3), 359–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2010.511771

Pillai, S. (2008). Speaking English the Malaysian way—Correct or not? English Today, 24(4), 42–45. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266078408000382

Rampton, M. B. H. (1990). Displacing the ‘native speaker’: Expertise, affiliation, and inheritance. ELT Journal, 44(2), 97–101. https://doi.org/10.1093/eltj/44.2.97

Ryan, S. (2006). Language learning motivation within the context of globalization: An L2 self within an imagined global community. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies: An International Journal, 3(1), 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427595cils0301_2

Saeki, T. (2015). Exploring the development of ownership of English through the voice of Japanese EIL users. Asian Englishes, 17(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/13488678.2015.998360

Saito, A. (2012). Is English our lingua franca or the native speaker’s property? The native speaker orientation among middle school students in Japan. Journal of Language Teaching and Research. 3(6), 1071–1081. https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.3.6.1071-1081

Saito, A. & Hatoss, A. (2011). Does the ownership rest with us? Global English and the native speaker ideal among Japanese high school students. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 6(2), 108–125. https://doi.org/10.5172/ijpl.2011.108

Saraceni, M. (2010). The relocation of English: Shifting paradigms in a global era. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-230-29691-6

Seilhamer, M. F. (2015). The ownership of English in Taiwan. World Englishes, 34(3), 370–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12147

Sifakis, N. C., & Sougari, A. (2005). Pronunciation issues and EIL pedagogy in the periphery: A survey of Greek state school teachers’ beliefs. TESOL Quarterly, 39(3), 467–488. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588490

Thomas, A. J., & Schwarzbaum, S. E. (2017). Culture and identity: Life stories for counselors and therapists. Sage Publications.

Appendix

Interview Questions Guideline

Dear Aya,

Thank you for your article. I was especially interested in the way you designed the study, as longitudinal approaches tend to be less common when it comes to language ownership and native speakerism. I agree that determining how “individual learners transform their attitudes concerning English language ownership over time and across contexts” is beneficial; after all, attitudes can change over time, especially as people gain new experiences. While, of course, the narratives of two respondents cannot lead to generalizations about how language learning intersects with ownership, the tripartite framework allows for a more comprehensive discussion of different factors that can indeed influence the degree to which one feels “ownership” over a second language.

In your discussion of the literature on Japanese perceptions of English, it may have been helpful to consider the current ecology of English Language Teaching in Japan and the degree to which English can indeed be promoted as an international language. Matsuda’s work in 2017, where she outlined ways to translate EIL principles into practice, or Heath Rose and Nicola Galloway’s proposals for Global English language teaching in 2019, provide more current perspectives on how this can actually be done in EFL classrooms. Such background knowledge would be instrumental in conveying to your readers what enables or constrains teachers in adopting such philosophies. In addition, the quote about Asian and African speakers’ Englishes being “looked down on” could have been unpacked a little more. You may know that increasingly, Filipino teachers of English (FTEs) in dispatch companies, JET, and private online eikaiwas are being hired to teach English in Japan. The work of Alison Stewart and Yoko Kobayashi may help illustrate this point. How has the increased reliance on teachers from the Outer Circle changed perceptions of English in Japan? As Damian Rivers has pointed out, race and native-speakerism are indelibly linked. Also, as Ruanni Tupas has pointed out through his new paradigm of “unequal Englishes,” hierarchies of Englishes persist, even within certain contexts. Therefore, it might be worth enriching your discussion of Japanese perceptions of English by considering the points above.

Your discussion of findings was interesting in terms of how you applied Seilhamer’s three dimensions. Regarding Saki, is there any other information she conveyed regarding her view that “native speakers as the ideal or complete model, in contrast with speakers of non-native varieties of English, including herself, which she perceived as incomplete”? Regarding Kenji, it would have been interesting to know what other factors may have played a part in him developing his attitudes towards English, or how he came to create an image of himself as an imagined member of an English-speaking community.

Lastly, for pedagogical suggestions, I think it is always helpful to provide readers with possible takeaways on how Global Englishes/EIL/WE can be promoted so that feelings of inadequacy can be eschewed. Please consider extending this part—revisiting the Global Englishes Language Teaching literature may help you come up with specific pedagogically informed suggestions to minimize feelings of inadequacy and maximize feelings of ownership.

I hope these comments and suggestions help. I was very interested to read your paper and wish you luck with your research.

Best regards,

Gregory

Dear Gregory Glasgow sensei,

Thank you very much for your encouraging comments and thorough feedback. I apologize for the delay in responding.

I recognized that the literature review needed more up-to-date discussions, so I am especially grateful for your recommendations regarding key recent literature. I have incorporated your suggestions into the revised version, which will be available in PDF format shortly.

Regarding possible takeaways on promoting Global Englishes/EIL/WE, I hope that the literature review in this paper, along with the voices of my research participants, will help raise awareness of who might be most adversely affected by the native-speakerist ideology. It would also be important for future research to explore how the polarization may be growing between those who are well-informed—who recognize the discriminatory and disempowering nature of rigid attitudes toward different language varieties—and those who remain unaware, and its outcome.

Additionally, while this idea may not directly answer your questions/suggestions, your feedback inspired me to reflect on the metaphor of “owning a house” versus “renting a house.” Is it truly the (sense of) “ownership” that matters for people as language learners/users, or could it be something else? Even in a small rented apartment, we can create a space that feels truly like home, inviting others and fostering great experiences. Perhaps the same applies to language. Revisiting this metaphor might offer valuable insights into reimagining language ownership and reevaluating its role in empowering emerging L2 users.

Thank you once again for this opportunity and for your invaluable guidance.

Best regards,

Aya Hayasaki