Haruka Ubukata, Kanda University of International Studies

Allen Ying, Kanda University of International Studies

Ubukata, H., & Ying, A. (2023). Japanese university students’ self-directed learning goals and

action plans elicited with the use of a reflection tool. Relay Journal, 6(2), 123 -149. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/060203

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

Supporting learners in developing skills to manage their learning outside the classroom is not an easy task for teachers. One way to take on this challenge is through reflection activities designed to raise learners’ awareness of themselves and their learning and help them identify how to maximize their learning opportunities both in and outside the classroom. In this study, we report on 41 Japanese university students’ reflection entries elicited by a reflection tool called the Wheel of Language Learning (WLL) (Kato & Mynard, 2016) and follow-up reflective questions. We identified the language and learning skills they were interested in improving and the actions they believed would help them improve those skills. Results show that, while the students chose different skills to focus on, speaking, confidence, and vocabulary were the most popular areas. The students came up with a variety of strategies and resources to improve their target skills. However, there were also areas where teachers may need to provide support to raise students’ awareness. At the end of the article, we provide limitations and recommendations for teachers interested in supporting learners with their self-directed learning through reflection activities.

Keywords: reflection, self-directed learning, learner awareness, language learning strategies, language learning resources

Language learning requires more than classroom learning if one wishes to be successful. Key to learners’ guiding their learning are self-directed learning skills. Self-directed learning, originating in the field of adult education, is “designed to help adults learn how to make their own decisions in accomplishing personal learning goals” (Hiemstra, 2013, p. 24). There has been a general agreement among researchers and teachers that conscious support for learners to raise awareness and control over self-directed learning skills (e.g., goal setting, making and implementing a plan, choosing appropriate strategies and resources), awareness and control over ways to learn and emotions, leads to learners’ greater autonomy (Curry et al., 2017). Reflection can play a key role in learners’ becoming aware of their learning in this process. However, it may not be an easy task for students to reflect deeply and effectively. A variety of tools has been developed to promote the process of reflection, and their effectiveness has been reported by researchers (e.g., Curry et al., 2023). This study reports on Japanese university students’ reflections elicited from a reflection tool, the Wheel of Language Learning (WLL), and follow-up reflective questions. Specifically, we analyzed the language and learning skills which students were interested in improving and the actions they came up with to improve those skills. We will first describe the research background on reflection in the field of language learning, followed by our research questions. We will then describe the method of the study and present results and discussion. We will conclude the article by addressing the study’s limitations and recommendations for language teachers interested in incorporating reflection activities in their classrooms.

Reflection and Language Learning

Reflection is an essential part of learning (Huang, 2021). In the process of reflection, learners think deeply about their learning, become more aware of how they learn, and self-regulate their learning (Mynard et al., 2023). While the term “reflection” has been conceptualized in many ways since Dewey (1933), a definition appropriate in our context would be that of Mynard (2023): “the intentional examination of experiences, thoughts and actions in order to learn about oneself and inform change or personal growth” (pp. 23-24). Learners reflect on their experience, make sense of it, and take action to make their learning more effective and successful.

While it is recognized by many that reflection is an important component of language learning, going deep into one’s thoughts is something a lot of learners struggle with. Sampson (2023), for example, analyzed written reflections of Japanese learners of English using Fleck and Fitzpatrick’s (2010) model and found that their reflections mostly remained at the surface level. Findings from other studies also indicate that it is often challenging for learners to reflect deeply, beyond mere descriptions or surface-level interpretation of events (Ambinintsoa & MacDonald, 2023; Sampson, 2023).

A number of tools and intervention activities have been developed to facilitate learners’ reflection. One of such tools is the Wheel of Language Learning (See Figure 1) (Kato & Mynard, 2016; Kato & Sugawara, 2009). Adopted from the coaching field, the WLL is a tool designed to help learners clarify the current situation of their learning. Using this tool, learners can visualize and evaluate their level of satisfaction with different areas of learning, for example, goal setting, time management, learning strategies, motivation, learning materials, and enjoyment. The tool also helps them to notice interconnections between different areas of learning. Furthermore, it can be used with lower-level students as the visual nature reduces the learners’ cognitive load. A recent study by Polczynska et al. (2023) on Japanese English as Foreign Language (EFL) university students suggested that the tool is viewed as beneficial from a learner’s point of view and that it facilitated their reflection process. The researchers’ students commented on the WLL, noting that it helped them to become aware of and clarify their strengths and weaknesses. Below are some of their students’ comments:

By writing “The Wheel of Language Learning,” I can see my strengths and what I should improve more. (p. 301)

Putting my thoughts together on paper helped me to discover my strengths and weaknesses more clearly. (p. 302)

With previous research confirming the effectiveness of the visual reflection tool, we did not examine the effectiveness of the tool itself in this study. Rather, our purpose was to understand areas of English learning that our students wanted to improve and analyze the self-directed learning ideas they believed would be effective. With a focus on the action plans our students described in their reflections, we intended to find the gap between what learners are already aware of and what they may not be, which is where teachers need to provide extra support. Our research questions are:

Research Question 1: What language and learning skills do students prioritize by using the WLL?

Research Question 2: What do students believe helps them improve their chosen skills?

Methodology

Participants

The participants of this study were 41 second-year university students majoring in English at a Japanese university. All of them were enrolled in a required English course for sophomores. The course was taught by Allen Ying, the second author of this study and a lecturer at the university, and the research was done by Haruka Ubukata, the first author and a learner advisor working with Allen’s classes among others. The university had assessed the 41 students’ levels of English as beginner to higher beginner based on their Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) scores and a university oral test at the beginning of the academic year. They were given a consent form and were explicitly made aware at the beginning of the first reflection session that responses were foremost for helping them to reflect and improve their language and/or learning abilities, and the activities were ungraded. They were also explained that participation or non-participation in the study did not impact their class grades. All students who participated in the study gave us permission to use their reflection survey responses. In the three reflection sessions we gave (explained below), all 41 students participated in the first one. In the second and third sessions, we had 38 and 37 students respectively, as a few were absent. However, we included all the students’ reflections in our data, as the study aimed not to compare students’ reflections for progress from one point to another but simply to examine the ideas they came up with. To anonymize and differentiate the students, we refer to them as S1 to S41.

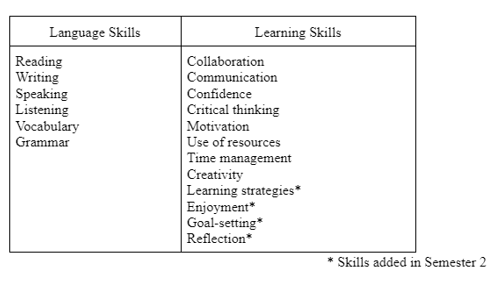

Reflection sessions

Our students participated in three reflection sessions in the second semester of their sophomore year. Each reflection session lasted 80 to 90 minutes, carried out in the first, the eighth, and the fifteenth week of the 15-week semester. In each of the three reflection sessions, students were given a list of language and learning skills (see Appendix A) and a blank WLL worksheet (Figure 1). From the list, they were asked to choose eight language and/or learning skills they considered important or meaningful and write the skills in the blank boxes surrounding the WLL. Then, they drew their level of satisfaction with each skill in the WLL, with 1 meaning not satisfied at all and 10 being completely satisfied.

Figure 1. Wheel of Language Learning (adapted from Kato & Mynard, 2016)

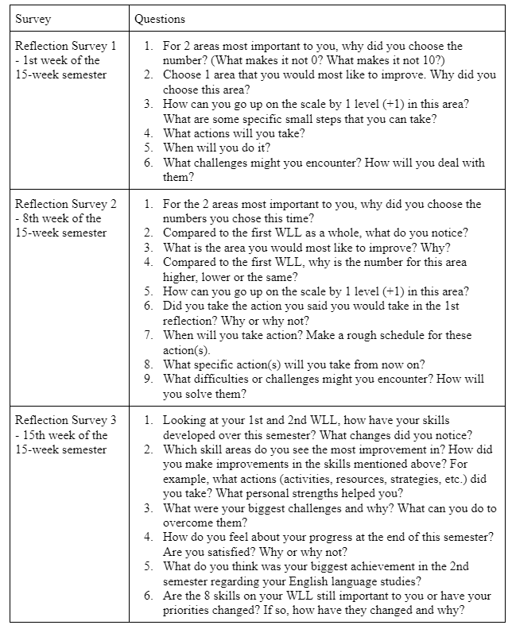

After completing the WLL, the students were given follow-up reflective questions in a Google Survey form (Appendix B). These reflection survey questions were adapted from the reflection activities provided by the English Language Institute’s and Self-Access Learning Center’s curriculum development team, which intended to help students find effective and suitable ways to learn (see Lyon et al., 2023, for more details). Our follow-up questions asked students to choose a skill on the WLL that they would like to prioritize for improvement and make a plan to improve that skill for the semester. These procedures, carried out in the first week of the semester, were replicated in the second (Week 8) and third (Week 15) reflection sessions with the exception of survey questions asking students to refer to their previous WLLs so that they could perceive improvement, lack of improvement and/or other changes. All the questions were given in English, and the students wrote their reflections on answering the questions in English as well. We revised our survey questions where we saw necessary for our students as we conducted the reflection sessions, but we ensured to keep the nature of the questions the same. Students were free to look up words in a dictionary or ask the teacher if they had any questions.

Data Analysis

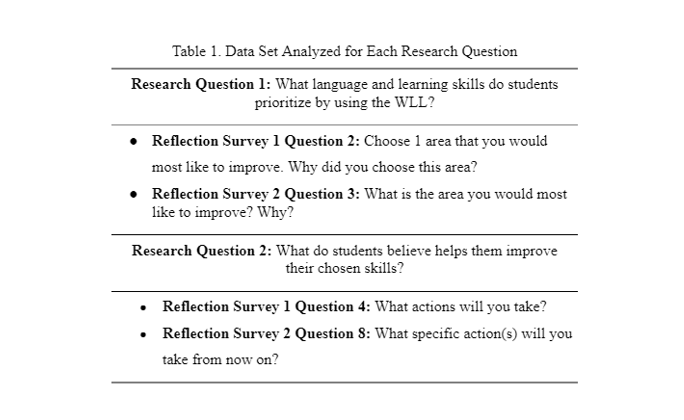

As this study aimed to glean what skills students prioritized in language learning at the time of this study and what actions students would take to improve their prioritized skill, we analyzed survey responses which were relevant to the research questions only. That is, responses from Reflection Survey 1, Question 2 and Reflection Survey 2, Question 3 were used to answer Research Question 1, while responses from Reflection Survey 1, Question 4 and Reflection Survey 2, Question 8 were analyzed for Research Question 2 (Table 1). To answer Research Question 1, we quantitatively counted and summed the skills students chose to improve in each reflection survey. To answer Research Question 2, we coded the data following Saldaña (2013) for the qualitative aspects of the survey responses. We individually familiarized ourselves with the data before coding, and then we ran a thematic analysis together by going through the students’ responses one at a time. We discussed our interpretation to reach an agreement and made efforts to keep the coding accurate to the students’ intended meaning.

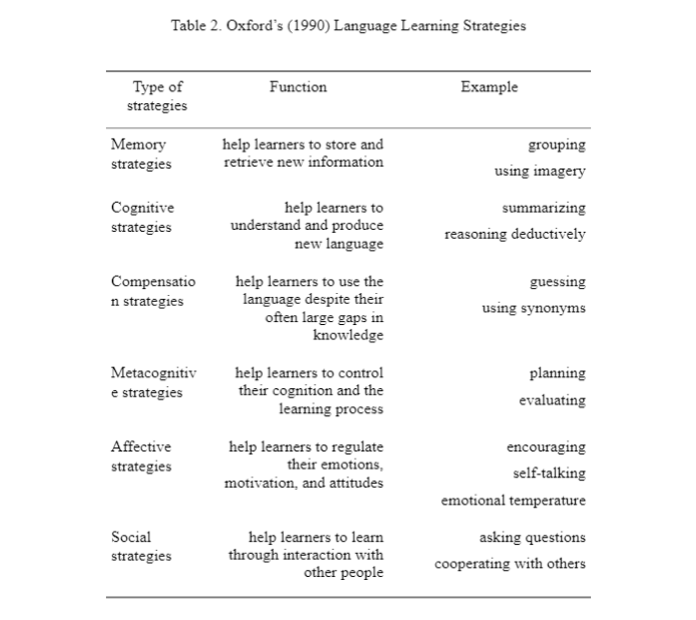

Students described their actions in terms of strategies and resources. To categorize the strategies that the students described, we used Oxford’s language learning strategy taxonomy (Oxford, 1990, pp.14-22). Table 2 summarizes Oxford’s strategy types with their functions and examples. For resources, we generated our own codes to categorize to analyze.

Results and Discussion

In this section, we present the results and discussions for each research question. After presenting the overview of target skill areas and action plans described by the students, we take a closer look at the strategies and resources they selected to improve speaking, confidence, and vocabulary, the three most chosen areas.

RQ1: What language and learning skills do students prioritize by using the WLL?

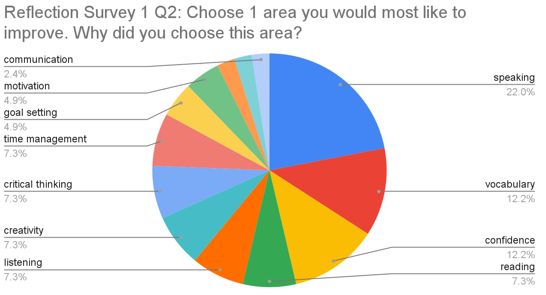

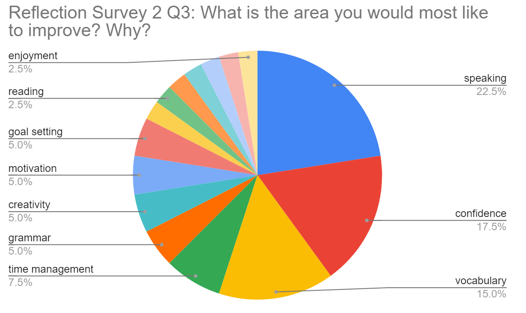

To answer our first research question, we analyzed students’ responses to Question 2 in Survey 1 and Question 3 in Survey 2, where students chose one skill that they most wanted to improve based on their reflection using the WLL. Figure 2 and Figure 3 below show these chosen skills in each reflection survey.

Figure 2. Skills Prioritized by Students in Reflection Survey 1

Figure 3. Skills Prioritized by Students in Reflection Survey 2

While different skill areas were raised in both surveys, speaking was the most chosen area of improvement at 22% in Survey 1 and 22.5% in Survey 2. The reasons for choosing speaking varied. One student who chose speaking emphasized the importance of speaking as a means of communication: “Speaking is important to communicate with someone because I am not able to ask questions or answer the question if I can’t speak English” (S1). Likewise, most students focused on the lack of their speaking skill:

…when I talk with other people, I frequently can’t explain my mind. (S2)

Now I often simple speak similar phrase. It make audiences discomfort to hear. (S3)

While those students thought of speaking more as a skill helping them to express themselves, one student realized the potential of improvement in other skills with the improvement of speaking, saying, “If I improve speaking skill, other skills would improve naturally” (S4).

Confidence and vocabulary were the second most chosen skills in Reflection Survey 1 and the second and the third most chosen, respectively, in Reflection Survey 2. A few students who chose confidence described that it would help their speaking and communication skills. In fact, they pointed out that the lack of confidence was the reason why they do not speak as much as they would like to:

I think if I have confidence, I can use English many situations. (S5)

I can feel free to ask teachers and friends what I don’t understand, and I think I’ll feel like trying a little more. (S6)

Additionally, it was evident in some of the students’ responses that they attributed making mistakes to a lack of confidence. One student wrote, “Sometimes, I can’t talk English well when we discuss something because I’m worry that my English may make a mistake” (S7). On the other hand, there was one student who was talking about their lack of self-confidence as a general weakness, not specifically related to language skills: “I have always been unsure of myself because I am not the best at taking care of myself. So, little by little, I need to gain confidence in myself” (S8). Conversely, the students who chose vocabulary as an area of improvement noted a wider range of other skills in relation to improving vocabulary, including communication skills, listening comprehension, and proficiency test scores. One student said, “I would like to improve my vocabulary skills. Because I want to improve speaking, listening and communication skills too but vocabulary skills is based on them” (S1).

In the reflection sessions, the students could decide their language learning priorities by themselves rather than being explicitly told by the teacher. Our results showed that they chose a range of skills, but three skills were more popular than others, and the reasons for choosing their skills to improve also varied. Nation (2014) suggests that learners should find their purpose of learning a language and focus their learning for that purpose. For example, if the learner wanted to learn English for business use, they should prioritize conversational spoken language first, then build up their business-related language skills. When teaching a group of students, adjusting class activities according to every student’s needs is not always feasible. However, using a reflection activity like the WLL and follow-up reflective questions, it is possible to create an opportunity for students to think about the skills they believe are important and why they believe so. As Nakata (2010) recommended, teachers should allow students to set long and short-term goals and attain self-monitoring and reflection skills, which would be affectively and cognitively beneficial to them.

RQ2: What do students believe helps them improve their chosen skills?

To answer our second research question, we summarize the actions described by the students to improve their chosen skills in the first and second reflection surveys. We first present the overall results of the strategies and resources described by the students, and then, in the next section, we focus more on the results of the three areas most chosen by the students: speaking, confidence, and vocabulary.

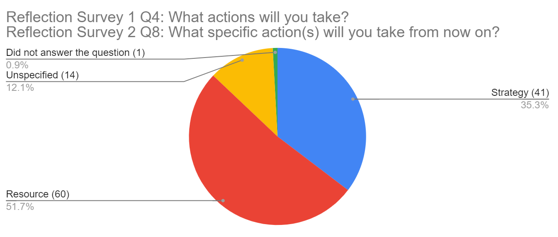

Overview of strategies and resources elicited in the reflections. Figure 4 shows the themes identified in Question 4 in Reflection Survey 1, “What actions will you take?” and Question 8 in Reflection Survey 2, “What specific action(s) will you take from now on?” where the students freely wrote their ideas about how they could improve the areas they chose. The majority of the students’ answers described strategies and/or resources to use. 14 instances did not provide specific action plans and one instance that did not answer the reflective question.

Figure 4. Actions Described in Reflection Survey 1 and 2 Combined

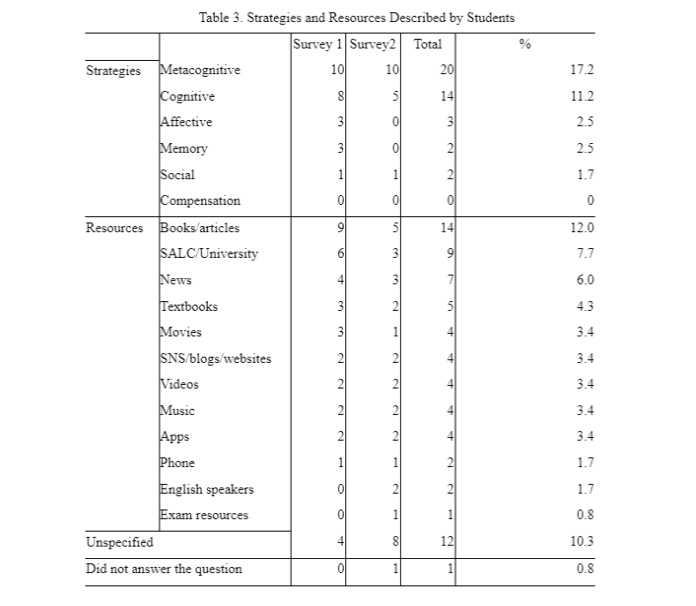

Table 3 shows the number of instances and the ratio of each category raised by the students. As we explained in the previous section, we used Oxford’s (1990) language learning strategy types as our coding themes to categorize the strategies. As to resources, we generated our own themes based on the data.

The students’ answers varied in terms of specificity and explanation regarding their actions. Some students only mentioned the resources they would be interested in using, while others described the strategy and resources they were planning to use: “For example, listen to western music on YouTube and after that you should look at the lyrics and hum them like shadowing. It is important to know the words and phrases even if you do not understand them completely” (S9). The strategy category the students most frequently described was metacognitive strategies. Among them, setting a target for vocabulary learning and a time for learning were common:

I try to remember 10 new words every day. It is difficult to continue this study, but I think I can achieve it because it is only 10 in a day. (S7)

When I ride train, do small or easy assignment. And also, it takes an hour. I think i can use this time too. (S10)

One student made a plan considering the level of resources they wanted to use: “I want to read one book in a month, or read one article in a week. At the first, I want to read easy and short books, and then I want to increase books’ difficulty level little by little” (S11).

The second most frequently mentioned category was cognitive strategies. These included singing along with music, speeding up audio, mapping and visualizing information, taking notes, copying sounds, and translating. As for translation, three students mentioned translating Japanese into English. One student wrote, “I like listening to the music in Japanese. I try to change the Japanese to English” (S12). This student seems to be trying to expand their learning opportunities by connecting English learning with their interest.

Three students raised affective and memory strategies. In all the comments on affective strategies, no specific actions were mentioned, but not being afraid of failure seemed to be key:

I am not afraid to fail. To gain as much confidence as possible, don’t be afraid to make mistakes. (S8)

I want to work on things that I am not good at without fear of failure. And I want to build my confidence little by little. (S6)

… try not to be scared when English conversation. Experience many fails. (S13)

On the other hand, memory strategies were raised regarding vocabulary learning. For example, “To improve my vocabulary skill, I will learn 5 vocabulary and make some frase [phrase] or sentences to use vocabulary before go to bed And then remember and review the 5 words when I get up” (S14).

Finally, there was one comment related to social strategies. The student’s target skill was communication, and they pointed out the importance of collaboration:

If you try to do everything by yourself, things will not go ahead, so if you are faced with something difficult, you should first consult with the people around you and try to solve it together. For this reason, it is a good idea to make it a habit to work together with others to solve problems. (S15)

In addition to strategies, the students mentioned various resources to improve the skills they chose. Books and articles were the most frequently mentioned:

I am going to go library and borrow some some English books or find some article from the internet. And, I want to read one book in a month, or read one article in a week. At the first, I want to read easy and short books, and then I want to increase books’ difficulty level little by little. (S11)

The second most frequently mentioned resource was the university’ s Self-Access Learning Center (SALC). The SALC offers human and material resources to support students’ language learning. Our students mentioned the human resources (e.g., a conversation practice area called Academic Support Area (ASA), tandem learning with exchange students):

I will go to talk is ASA at least once in two weeks. (S16)

I use SALC. There are curriculum that I and international student teach our language each other online. So I would like to try to use it. (S7)

Speaking, confidence, and vocabulary. As explained earlier, the areas the students chose to work on the most were speaking, confidence, and vocabulary. In this section, we summarize and discuss the action plans described by the students, focusing on the strategies and resources.

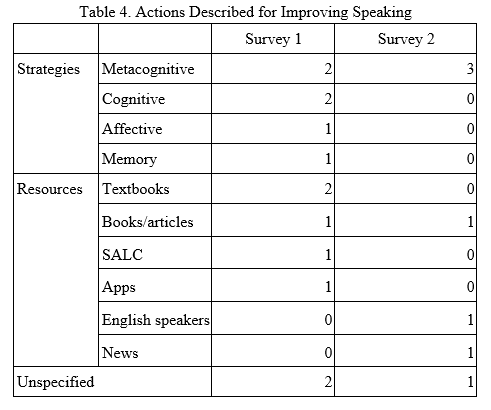

In each survey, nine students stated that they wanted to improve their speaking. Table 4 shows the strategies and resources for improving speaking described by the students in their response to the reflective questions “What actions will you take?” (Reflection Survey 1) and “What specific action(s) will you take from now on?” (Reflection Survey 2).

Many of the students wrote about building knowledge, such as vocabulary, rather than creating actual speaking opportunities:

I should learn vocabulary to improve my speaking skills. So I borrow the vocabulary books at kuis [the university] or libraries. I will learn about new 15 words. I will try to memorize them and take some tests myself. (S1)

I will study words inn the train to go to school and research news in English. It will improve my many skills. (S17)

As vocabulary is “the building blocks of language” (Al-Dersi, 2013, p.74), it is not unexpected that students see the connection between learning vocabulary and improving speaking. However, it will not necessarily lead to improvement in speaking skills unless learners put it into practice in speaking. Knowing a word’s form and its meaning may be enough for reception, but production requires learners to know a wider range of vocabulary knowledge (Schmitt, 2014). Studies also confirm that productive vocabulary skills are more advanced than receptive skills (e.g., Laufer & Paribakht, 1998; Nemati, 2010). Nation (2014) states that learners need balanced practice for receptive and productive skills for effective language learning. From our teaching experience, we have observed that it is a common pitfall that learners study vocabulary and do not use them in speaking, not realizing the gap between their target area and the practice they need.

Another important point to note on learners choosing materials is that they might easily fall back on a comfortable resource rather than try out new resources that better match their new goals. To take one example, one student chose speaking as her language skill to improve. She was aware of the importance of that skill. However, her action plan was simply to continue using a grammar textbook she used to use in junior high school and high school:

(Question: Choose 1 area that you would most like to improve. Why did you choose this area?)

Area 1 Speaking: If I can speak English fluently I could talk with many people and I’m interested in teacher so I want to improve my skill. (S18)

(Question: What action will you take?)

Checking the grammar book again which used in my junior high school and high school. So I want to do English grammar book again. (S18)

It is not described what kind of grammar textbook she meant. Still, the fact that she did not mention actual speaking using the grammar she would study seems to indicate that she might need support from others (e.g., teachers, learning advisors, peers) to effectively choose language learning resources. While past research has shown that students may enjoy trying new ways of learning in learning self-directed learning skills (Curry et al., 2017), some might need support (e.g., in-class instruction) to experiment with new resources.

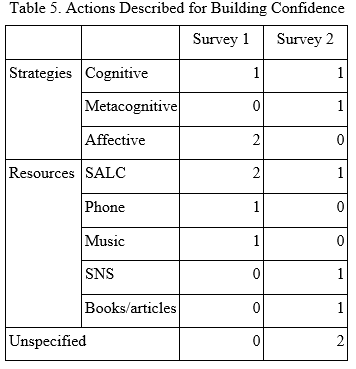

Confidence was the second area that the students chose the most. Table 5 shows the strategies and resources described by the students who chose this area to improve. Five students in Survey 1 and seven students in Survey 2 chose Confidence as their focus area for improvement.

Some students who chose confidence as a skill to improve connected confidence with practice (e.g., learning vocabulary, speaking the target language with other people). Using “a lot” of English is one way they believed could help to build confidence: “I try to use English a lot. For example, reading, speaking, writing, thinking in English. I set my iPhone English version. I try to use SALK [the self-access center of the university]” (S5).

There was also a student who wrote about facing what they are not good at to build confidence: “I want to work on things that I am not good at without fear of failure. And I want to build my confidence little by little. I think this is the best” (S6). Similarly, another student wrote, “I am not afraid to fail. To gain as much confidence as possible, don’t be afraid to make mistakes” (S8). These comments show students’ reflecting on affective aspects of a learning process, but most of the responses in this area were about either language practice or resources for practice. While actual use of language is necessary to improve language skills, there is a possibility that students may not be aware of specific strategies to deal with a lack of confidence or that they do not recognize such strategies as effective as practicing the target language. This supports the idea that learners are not necessarily aware of or understand the importance of affect in language learning (Shelton-Strong & Mynard, 2018). Affect and language performance are closely related (Oxford, 2017), and our results seem to point to the necessity of awareness raising for learners to develop skills to manage their affective state.

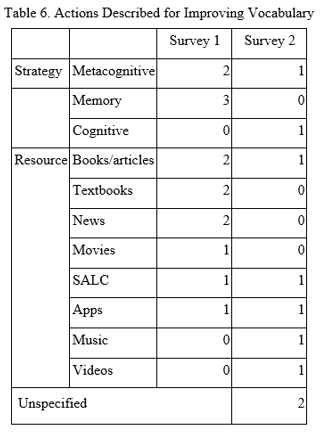

Finally, vocabulary was also a popular area among the students. Table 6 summarizes the strategies and resources raised by the students who set vocabulary as a target area of improvement. Five students in Survey 1 and six students in Survey 2 stated they wanted to improve this area.

Metacognitive, memory, and cognitive strategies were raised by the students who chose vocabulary as an area to focus on. In the example stated in the previous section of the overview of strategies and resources, one student (S14) was planning to regulate the learning process by setting a target number of words to study (metacognitive strategy) and to learn them by creating mental connections or “[p]lacing new words into a context”, which is a memory strategy (Oxford, 1990, p. 41). Another student wrote, “I made my vocabulary note and take note that I don’t understand meanings” (S19). Note taking is one of the cognitive strategies that help learners organize their language input into manageable portions, preparing to use the new knowledge in another context (Oxford, 1990).

Other students seemed to focus more on input and reviewing. One strategy often mentioned was reading and writing vocabulary, as shown in the following example: “I read vocabulary book 3 times or more. And I write vocabulary Japanese to English and English to Japanese. I will sticky note on the wrong words” (S20). From our observations, using vocabulary books to memorize English words is relatively common among for Japanese students. They often read their vocabulary book multiple times and test themselves to see if they can remember the definitions in their first language or the target English words from Japanese definitions. If they do not remember, they mark the vocabulary item to review later.

While the comments of the students mentioned above were simple descriptions of how to learn (strategies), three students clearly articulated their language learning beliefs and chose resources that matched these beliefs:

I will news paper or book in English and go to library or SALK to find English reading. […] Reading sentence is useful to know new words. (S17)

I take the challenge to listen any more words using movie. I think the best way to improve the listening skill is to listen to the words in fact. (S20)

I hope to read vocabulary books like TOEFL books. It is written academic words so that it is good for me to learn not only normal words but also more academically words. (S21)

These students seem to know what resources are available for them and are choosing resources congruent with their own beliefs about language learning. In other words, in addition to their awareness of resources, they also have self-awareness, which indicates that they are, to a certain degree, autonomous language learners (Kato & Mynard, 2016). While we cannot tell whether the other students who simply described their future actions also had rationale from their beliefs, the comments by these students here may be an instance of learners’ taking ownership of their learning by exercising autonomy, “the psychological freedom to act in accordance with one’s beliefs and interests” (Mynard & Shelton-Strong, 2022, p.3).

Conclusion

In this study, we examined language and learning skills our Japanese university students were interested in improving and the strategies and resources they came up with by engaging in a reflection activity using the WLL. Although their areas of interest varied greatly, speaking, confidence, and vocabulary were the most popular. There were several students whose reflection entries were not specific. Still, most of the students described a variety of strategies and resources to improve their target areas, suggesting that they have some ideas of what action to take. At the same time, it was also implied that some areas might require more support from teachers in order to raise students’ awareness, for example, affective strategies, balanced input and output practice, exploring new resources, and raising awareness of self.

Here, we would like to address the limitations of our study. First, as a small-scale study with 41 Japanese university students, the results cannot be generalized to a broader population and different contexts. In addition, we only analyzed our students’ written reflections. More insights might have been gained through other research methods, such as interviews. We also did not conduct follow-up research on the students’ described actions. Therefore, we cannot tell whether the reflection activity actually led to action on the students’ part afterward.

Despite the above limitations, the study provided useful insights into the language and learning skills Japanese university students may be interested in improving and the strategies and resources that they may believe are effective in achieving the improvement. For teachers interested in incorporating reflective activities into their classrooms and facilitating students’ self-directed learning, we would like to offer the following recommendations:

- Raise awareness of affective strategies by providing explicit training. Students may know different resources and ways to use them, but they may not pay as much attention to how their learning is influenced by affective factors and how they can regulate their emotional state to maximize their learning. Teachers could explicitly explain the role affect plays in language learning, have students reflect on their experience, and equip them with affective strategies by providing specific strategy examples (see Oxford, 1990, pp.140-144).

- Help students reflect on their learning balance. In planning their own learning, students may overemphasize one skill and barely use other ones. For example, they may only study vocabulary by reading a vocabulary book without using it in their target situation (e.g., conversations with friends or writing an essay). Teachers may address this issue by presenting some common situations and discussing how the learning plan can be adjusted with students.

- Encourage students to evaluate the appropriateness of their chosen resource and to explore new resources. Students may choose resources based on their familiarity rather than the appropriateness of those resources. Students need to carefully examine the connection between the skill they want to improve and the resource they select. They may benefit from input from others, especially when they embark on new target skills. Teachers could encourage students to share ideas as well as provide example resources.

In addition to the recommendations above, when implementing such a reflection activity as ours, it is important to first explain the concept of reflection and the role it plays in students’ learning. Using guiding questions is also useful to facilitate the reflection process (Huang, 2021). They should be phrased in simple and easy-to-understand language for students. Last but not least, depending on the level of students, providing support in their first language (L1) may be necessary. Teachers could include L1 explanations or allow students to respond in L1 when necessary.

Future research could further explore learners’ ideas for improving their language learning. This will provide teachers with more insights into how they can facilitate learners’ self-access language learning.

Notes on the Contributors

Haruka Ubukata is a Learning Advisor at the Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS). She has completed the Learning Advisor Education Program at the Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education (RILAE). She holds an MSEd in TESOL from Temple University Japan Campus.

Allen Ying is an English lecturer at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS). He received his MSEd. in TESOL from Temple University, Japan Campus, and he has a background in graphic design with a BA in Studio Arts from the University of California, Irvine.

References

Al-Dersi, Z. E. M. (2013). The use of short stories for developing vocabulary of EFL learners. International Journal of English Language & Translation Studies, 1(1), 72-86.

Ambinintsoa, D. V., & MacDonald, E. (2023). A reflection intervention: Investigating effectiveness and students’ perceptions. In N. Curry, P. Lyon, & J. Mynard (Eds.), Promoting reflection on language learning: Lessons from a university setting (pp. 112-131). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781800415591-011

Curry, N., Lyon, P., & Mynard, J. (Eds.). (2023). Promoting reflection on language learning: Lessons from a university setting. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781800415591

Curry, N., Mynard, J., Noguchi, J., & Watkins, S. (2017). Evaluating a self-directed language learning course in a Japanese university. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 14(1), 17-36. https://www.sdlglobal.com/_files/ugd/dfdeaf_385a2e4d19254f968487b6058464e00c.pdf

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. D.C. Heath & Co Publishers.

Fleck, R., & Fitzpatrick, G. (2010). Reflecting on reflection: Framing a design landscape. In OZCHI ‘10: Proceedings of the 22nd conference of the computer-human interaction special interest group of Australia on computer-human interaction (pp. 216-223). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/1952222.1952269

Hiemstra, R. (2013). Self-directed learning: Why do most instructors still do it wrong? International Journal of Self-directed Learning. 10(1), 23-34.

Huang, L. S. (2021). Improving learner reflection for TESOL: Pedagogical strategies to support reflective learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429352836

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

Kato, S., & Sugawara, H. (2009). Action-oriented language learning advising: A new approach to promote independent language learning. The Journal of Kanda University of International Studies, 21, 455-475. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237226385

Laufer, B., & Paribakht, T. S. (1998). The relationship between passive and active vocabularies: Effects of language learning context. Language Learning, 48(3), 365-391. https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.00046

Lyon, P., Yoshida, A. J., Yoder, H., MacDonald, E., Ambinintsoa, D. V., & Curry, N. (2023). Fostering learner development through reflection: How the project started. In N. Curry, P. Lyon, & J. Mynard (Eds.), Promoting reflection on language learning: Lessons from a university setting (pp. 53-67). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781800415591-007

Mynard, J. (2023). Promoting reflection on language learning: A brief summary of the literature. In N. Curry, P. Lyon, & J. Mynard (Eds.), Promoting reflection on language learning: Lessons from a university setting (pp. 23-37). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781800415591-005

Mynard, J., Curry, N., & Lyon, P. (2023). Promoting reflection on language learning: Introduction. In N. Curry, P. Lyon, & J. Mynard (Eds.), Promoting reflection on language learning: Lessons from a university setting (pp. 3-12). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781800415591-003

Mynard, J. & Shelton-Strong, S. (2022). Self-determination theory: A proposed framework for self-access language learning. Journal for the Psychology of Language Learning, 4(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.52598/jpll/4/1/5

Nakata, Y. (2010). Toward a framework for self-regulated language-learning. TESL Canada Journal, 27(2), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v27i2.1047

Nation, P. (2014). What do you need to know to learn a foreign language? Victoria University of Wellington.

Nemati, A. (2010). Active and passive vocabulary knowledge: The effect of years of instruction. The Asian EFL Journal Quarterly, 12(1), 30-46.

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Heinle & Heinle.

Oxford, R. L. (2017). Teaching and researching language learning strategies: Self-regulation in context (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Polczynska, M., Goncalves, J., & Castro, E. (2023). Fostering interactive reflection on language learning through the use of advising tools. In N. Curry, P. Lyon, & J. Mynard (Eds.), Promoting reflection on language learning: Lessons from a university setting (pp. 291-306). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781800415591-021

Saldaña, J. M. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Sampson, R. (2023). Encouraging introspection on speaking performance in class: Findings from student reflections. In N. Curry, P. Lyon, & J. Mynard (Eds.), Promoting reflection on language learning: Lessons from a university setting (pp. 81-90). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781800415591-009

Schmitt, N. (2014). Size and depth of vocabulary knowledge: What the research shows. Language Learning, 64(4), 913-951. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12077

Shelton-Strong, S. J., & Mynard, J. (2018). Affective factors in self-access learning. Relay Journal, 1(2), 275-292. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010204

Appendices

Appendix A

Important Skills of Language Learning Developed by the University’s English Curriculum Team

Appendix B

Reflection Survey Questions

Dear Haruka and Allen,

It was my pleasure to be invited to review your article. I found your work both insightful as it is enjoyable to read. As you pointed out in the article, reflection matters when it comes to language learning. As such, the findings reported have offered useful contribution to the literature on language learning and advising.

I only have a few minor suggestions to offer, and I hope they are of some help. Please see them below:

1-It’d be better if some areas that require teacher support were added to the abstract. Since providing support is one of the central topics in the article, the reader might be interested to know early on.

2-In the Reflection sessions under Methodology, three reflection sessions were mentioned. It’d be more useful if the purposes of each were added, so readers can better see why there were three.

3-Data analysis: The first paragraph could be more concise, and the reason why Survey 3 wasn’t used could also be added.

4-Table 2: Emotional temperature?

5-Conventions: Numbers should be written in words when they come at the beginning of the sentence. In addition, both numbers and percentages should be used. For example, Five students (X%) selected vocabulary as their goal of improvement.

Overall, your work demonstrated that the research was rigorously carried out and coherently presented.

Dear Ha,

Thank you so much for your encouraging comments and feedback.

We have made changes based on your suggestions, and the article will be available in a PDF file.

As for the number/percentage conventions, there were a few parts where we did not include percentages because they were quite low and our purpose was not necessarily to compare the numbers. However, we did add for the other parts.

We certainly appreciate the opportunity to have you review our article. Thank you again for your feedback!

Haruka & Allen