Aleksandr Gutkovskii, Toyo University

Gutkovskii, A. (2024). Examining the Interplay between Autonomy and Hidden Beliefs about Language Learning. Relay Journal, 7(1), 54-65. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/070106

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

This paper provides a reflection on how my beliefs about grammar in language learning shaped my teaching practices. After a brief description of my language learning journey, I outline my experience teaching second-year university students and introduce the autonomous learning project that I implemented in my classes. Then, I reflect on how this project came into conflict with my implicit beliefs about the importance of accuracy for language learning and consider insights that stemmed from this reflection. The paper concludes with the practical ideas that other teachers might use to investigate their teacher beliefs and avoid the conflict between beliefs and classroom practices.

Keywords: teacher beliefs, learner autonomy, Japanese university, reflection, grammar-based instruction

The gap between teachers’ beliefs and their actual classroom practices is a topic that has been widely discussed in the literature. Several studies demonstrated that teachers might believe in concepts such as communicative language teaching, discovery learning, and autonomy, but their classroom practices are still reported to be teacher-centered and grammar-driven (Borg & Al-Busaidi, 2012; Borg & Alshumaimeri, 2019; Farrell & Lim, 2005; OECD, 2009). This problem is especially apparent regarding learner autonomy. Studies report that teachers tend to view learner autonomy as positive and desirable, yet they might shun promoting autonomy in their classes due to different reasons, including its perceived low practical feasibility which, in turn, creates a gap between their beliefs and practices (Borg & Al-Busaidi, 2012; Borg & Alshumaimeri; Li, 2023). Recently, I had a chance to reflect on this gap after experiencing a conflict between my positive beliefs about autonomy and my teaching practices based on grammar teaching.

At the time of the described events, I worked as an assistant lecturer and a language advisor at a private university in the Tokyo area. I taught second-year students and conducted language advising in a university’s English Advising Program. Through my educational and work experiences, I developed a deep interest in learner autonomy and started implementing a framework to foster autonomy not only in my advising sessions but also in my classes. However, after introducing an autonomous learning project in my class, I soon realized that this project came into conflict with my practice of teaching grammar. The conflict became a turning point that spurred reflection and made me question the gap between my beliefs and practices. In this paper, I will address the details of the said conflict and describe how it underscored the need for deeper self-reflection.

My Background as a Language Learner, Teacher, and Advisor

First, I would like to outline my own language learning journey and explore the roots of the beliefs that I currently hold. I was born in Russia and learned English as a second language from grade school to university. My early experience of learning languages can be described as two-fold. On the one hand, I grew up in an educational system that prioritized accuracy over fluency with most of the class time being spent on intensive reading, grammar exercises, and test drills. On the other hand, I had a deep interest in cinema which led me to consume hours of YouTube video essays in English trying to learn about film history and production. These two facets of learning rarely overlapped. Studying to pass tests was a necessary chore whereas watching video essays was a genuine passion. Later, I started reading novels and watching movies in English thus exposing myself to as much language input as possible while also practicing my production skills by chatting online with English speakers. Through this experience, I distanced myself from grammar-based instruction and came to believe that learning a second language is a matter of extensive and relevant input combined with practice. In other words, I prioritized fluency over accuracy.

After relocating to Japan, I pursued an MA in TESOL and subsequently started to work as a university lecturer. As I became a novice educator, my beliefs about language learning transformed into beliefs about language teaching. Hence, in my classes, I tried to focus on fluency and expose my students to extensive reading and listening. At that time, I started to study Japanese more deliberately by making learning plans and using time-blocking. Through this experience, I became interested in learner autonomy, which can be defined as “a capacity to control important aspects of one’s learning” (Benson, 2013, p. 839).

Autonomy brought a sense of control and precision into my learning, and later I had a chance to apply the autonomous learning principles when I started to work as a language advisor at my university’s English Advising Program. My role as an advisor was to help learners be more reflective and encourage them to take responsibility for their learning by setting goals, creating learning plans, and identifying areas for improvement. Thus, my advising role closely aligned with the perspective of Kato and Mynard (2016), who see advisors as facilitators for reflective dialogue rather than knowledge dispensers. Through individual advising, I discovered a sense of great joy in helping my advisees on their learning journey. For instance, one of my advisees became increasingly more self-directed as she progressed from being reliant on my recommendations to being able to independently set learning goals and create learning plans for herself. This improvement in self-directedness was also connected to confidence and language growth as the advisee started to shift from using Japanese to English during our sessions. Every time I witnessed my advisees’ progress, I thought of how I could promote autonomy among the students in my classes as well.

I came to realize that many of my students had grown up in an educational context similar to mine. They transitioned into the university from an environment characterized by high-stakes tests and a lack of focus on the communicative use of English during the classes. The negative influence of cramming for high-stakes entrance exams and limited exposure to communicative English instruction at schools are often cited as factors that decrease Japanese learners’ motivation (Allen, 2016; Osterman, 2014; Sakui, 2004). As a result of being exposed to such learning environment, some of my students lacked motivation for learning English in general. Others were eager to learn but were too reliant on explicit teacher guidance. This overreliance on a figure of authority is cited as a factor that can hinder students’ autonomy (Allen, 2016; Sakata & Fukuda, 2018). I came to believe that in this context, my students needed not only language skills but also the skills that would develop their autonomy. Hence, I started thinking of how I could introduce autonomous learning in my classes.

Class Context, Structure, and Syllabus

In the fall of 2023, I transitioned from teaching first-year students to teaching second-year ones. Unlike freshmen, whose class met twice a week, second-year students only had one English class per week with a total of 15 meetings throughout the semester. Fewer class meetings meant that I needed to carefully plan what to include in the course and what to leave out. Out of six classes I had, one class was particularly memorable. This class, passed on to me by another teacher, was of a lower-intermediate level. In the spring semester, the previous teacher focused on grammar, weekly news reports, presentation skills, and midterm and final tests focused on grammar assessment. Given these characteristics, this class will serve as the primary focus of the current reflective paper.

Being confident that considering previous grammar instruction students could handle basic tenses with some scaffolding, I decided to implement the autonomous learning project. I will describe the project in detail in the next section, but first I will outline a big picture of the course syllabus.

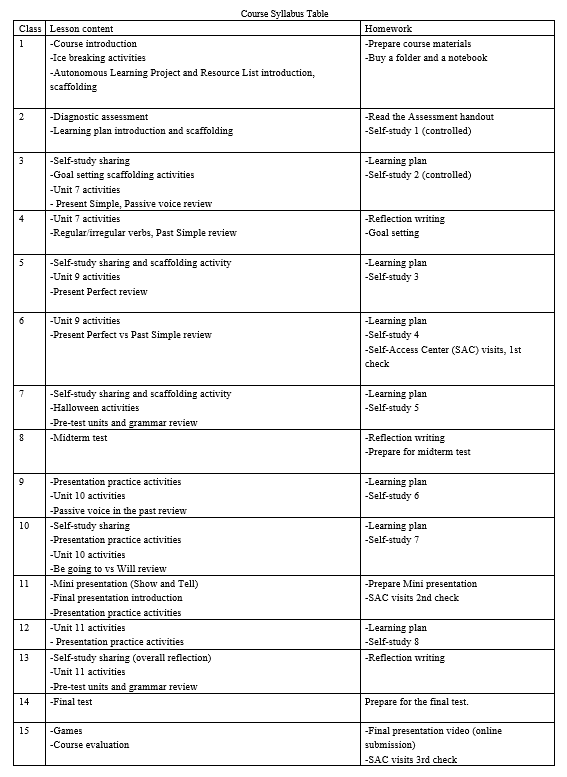

My university had a textbook requirement for this course, but apart from that, I had a lot of freedom in designing my syllabus. The course that I designed had four main elements: the autonomous learning project, grammar review, activities related to textbook units, and presentation practice in the second part of the semester. The course also featured one diagnostic assessment that I planned to deliver in the second class to see how well students could write sentences with the grammar points they had learned in the spring semester.

I decided to use two written grammar testsーa midterm and a final oneーfor assessing students’ review progress. The tests were geared towards open-ended questions and writing short paragraphs with target grammar points. This decision was based on several factors. I reckoned the large number of grammar points that we needed to review warranted the usage of tests rather than fluency-based assessments such as speaking tests or presentations. Another reason is that the students were already familiar with this format based on their previous semester with the other teacher. You can refer to the syllabus table in Appendix 1 to see more detailed information on the course structure.

Autonomous Learning Project

After piloting smaller components of the project, the final iteration of the project was done in the fall semester of 2023, and that will be the focus of this reflection. The project was based on six main elements: scaffolding activities, goal setting, creation of learning plans, self-study, group sharing, and written reflections. Most of these elements happened outside of the classroom and were assigned as homework, with group sharing and scaffolding activities taking place in class. Below, I try to outline the main components of the project and demonstrate how they related to each other.

At the beginning of the semester, I introduced the project and a list of language learning resources. Then, students were assigned to practice reading and writing, and then listening and speaking at home for the first three weeks. The skills were selected by me, but the students could choose the resources and preferred method of study. This controlled practice was done to familiarize students with different resources and encourage them to try different methods of learning. Starting from the second week, the weekly learning plans were introduced as homework in which students decided on the specific activities and time of learning.

Starting from the third week, students were given the freedom to choose their preferred area of study and asked to set their learning goals. For goal setting, I used the SMART Goal framework to ensure that students’ goals were specific. SMART stands for the following features of a goal: specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-based (Reinders, 2020). SMART goals were first scaffolded in class using daily life examples. After that, students brainstormed reasons for learning languages and wrote their SMART goals for English learning. Below in Figure 1 you can see an example of an initial SMART goal written by one of my students using an advising tool adapted from Kato and Mynard (2016, pp. 54-55). Initially, students struggled with making specific and measurable goals, so as the semester progressed, we revisited their goals to make them more specific and detailed. Students used the SMART goals as a basis to create their weekly learning plans and engage in self-study.

Figure 1. An Example of a Student’s SMART Goal

Self-study was the main component of the autonomous learning project. Students could choose the study area, materials, and methods. They were required to engage in self-study for at least 2 hours a week and submit specific proofs of their progress every week in the form of a portfolio. Every week, I would check students’ work and give them feedback. Some of the students chose to read and summarize news, a familiar activity that they had previously done in the spring semester. Others read manga in English, watched videos, did TOEIC practice, and attended speaking sessions at the Self-Access Center. The self-study was supported by occasional in-class scaffolding activities aimed at learning how to maintain motivation and measure learning progress. Twice a month we had sharing sessions in which students shared their learning experiences in groups and gave each other advice. Finally, students were asked to write monthly reflections on their self-study tracing learning progress and sharing challenges.

In this project, I saw myself not only as a teacher but also as an advisor who monitors students’ progress and advises on useful study techniques and resources. The role of advisor was partly based on the ideas of Kato and Mynard (2016). They describe an advisor as a person who, instead of prescribing a predetermined course of action, encourages learners to make informed decisions and take control of their learning. I designed the project as the main component of the course. Most of the assessment was geared towards it with 35% of the final grade allocated to the project-related activities and assignments. The grammar tests were worth 20% of the final grade (10% each), but I initially viewed grammar as a secondary element of the course used only to solidify previous grammar knowledge and put it into productive practice. Unfortunately, my initial plan changed shortly after the beginning of the semester.

The Beginning of a Conflict

At the beginning of the semester, I ran a diagnostic assessment and found that students struggled to make sentences with basic tenses. Distinguishing the present perfect from the past simple seemed especially challenging for them. At that time, I made a decision to focus more on the grammar component of the course. Later, I realized that this incited a conflict between my beliefs and teaching practices. I wrote in my reflection journal that I kept at that time: “I would fail as a teacher if, by the end of the semester, my students would not be able to tell the difference between Past Simple and Present Perfect.”

As I started spending more of the class time addressing grammar usage, this component of the course became increasingly dominant in my practice. Tense reviewーwhich I originally set only as a secondary activityーturned into a rabbit hole as I struggled to find time to balance grammar-based instruction with the autonomous learning project. I could not ignore the fact that my students struggled with grammar, yet teaching grammar resulted in tension and, subsequently, conflict between my beliefs and classroom practice.

The Aha Moment

I envisioned grammar tests as a review of what students learned in the previous semester with a greater focus on production as opposed to close-ended questions. However, I soon realized that instead of reviewing basic grammar points, my class would need to relearn some of them. One particular class struggled more than the others, so I spent most of my effort and class time trying to practice the target grammar before the midterm test. When the test day came, and I checked my students’ work, the results were rather poor.

In the week following the test, we did the test review, and that was the moment when I realized how far I had distanced myself from my initial goals and beliefs. Incidentally, this class meeting was observed by one of my senior colleagues who mentioned that my explanations were clear, and students were focused and cooperative. The class was far from being a total disaster, yet I could not shake the heavy feeling of disappointment with myself. Later, I had a post-observation meeting with my colleague, and preparing for this meeting gave me a chance to deeply reflect on this sense of disappointment.

I realized that despite my initial beliefs and aspirations for setting an autonomous learning environment, I had entirely shifted in the direction of teaching grammar. Not only was I focusing more on grammar, but I was also “teaching for a test,” something that I would not normally do. Moreover, I was not doing it because I was forced to but rather because I was convinced that it would be beneficial for my students.

Reflection points

Upon reflection, the main question that bothered me was “Why did I even choose to focus on grammar in the first place?” My university provided a lot of flexibility and did not require tests as a form of assessment, so how did I end up “teaching for a test”? I came to the following realizations.

Hidden beliefs

Despite my strong advocacy for fluency and autonomy, it seems that I still had some hidden beliefs about the importance of accuracy for language learning. Additionally, teaching grammar felt comfortable since I had previously experienced grammar-based instruction and was able to communicate the nuances of grammar usage to my students. I realized that my preoccupation with distinguishing tenses might have stemmed from the desire to teach my students “correct English” at all costs. As a result, I was ready to sacrifice fluency, class time, and developing students’ autonomy just to reach this artificial bar.

Lack of experience and internalized values

As I had never taught second-year students, I asked many of my immediate colleagues for advice. By doing so, I learned that most of them had implemented grammar tests in their second-year classes. Listening to their recommendations, I convinced myself that this was the most appropriate way to assess my students. In hindsight, the decision to focus specifically on lecturers who taught second-year students might have hampered my understanding of the situation. I should have asked more colleagues, even those who taught slightly different levels.

Low awareness of how my beliefs are formed

This reason is closely related to the two previous ones stated above. I assumed that my teaching beliefs were static and that I knew them well. However, through reflection, I discovered that I had done little to investigate my beliefs and how they can be shaped by external factors such as colleagues, students, and curriculum. I realized that going forward, I need to be more reflective and carefully trace the sources of my beliefs and assumptions.

Reflecting on how but not why

My reflection during the semester was mostly centered around the methodological aspect of teaching without focusing on the rationale behind my decisions. I spent a great deal of time trying to devise elaborate activities to practice and test grammar. Yet, I did not question my assumptions about the importance of accuracy that underlie my grammar teaching. I should have asked myself, “Why do I think that distinguishing between tenses is so important?” Going forward, I hope to engage in more deliberate and structured reflective practice by finding and analyzing critical incidents that happen during my teaching. Critical incidents are memorable eventsーboth positive and negativeーthat can be used to reevaluate one’s practices (Tripp, 2011). In order to find appropriate critical incidents to reflect upon, I plan to focus on the events that are emotionally relevant to me. An emotional response to an event can help to frame it as a critical incident which, in turn, will become a starting point for reflection.

I chose to use written reflections based on Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle framework (see Figure 2; Gibbs, 2001). This framework incorporates the reflection on feeling that will hopefully help me explore the emotional implications of my teaching practice. By identifying critical incidents and investigating my emotional response to them, I hope to gain a better understanding of how my beliefs shape my teaching practices. Hopefully, this type of emotion-based reflection can be useful for other teachers to investigate the roots of their beliefs and avoid conflicts such as the one described in this paper.

Figure 2. Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle

Practical Recommendations

Next, I would like to list some practical recommendations for teachers who might experience a conflict between their beliefs and practice. The following recommendations are by no means universal as dynamics between beliefs and practices are highly dependent on educational context.

You can start by reflecting on your teaching and try to examine how your beliefs are reflected in your practices. If there is a gap between your beliefs and practices, use a step-by-step reflection to identify the possible roots of this gap. In your reflection, try to start by investigating the theoretical basis of your beliefs and then move to how your beliefs influence your practice. In other words, start with why and then move on to how.

Another step you can take is to consider your course goals and think about how they relate to each other. In my case, the goal of grammar review, albeit communicative, did not fit well with the autonomous project. As a result, I had to constantly switch between the roles of a teacher and advisor, deepening the gap between my beliefs and practices. If one element of the course does not contribute to what you are trying to achieve, consider removing or changing this element.

Finally, talk with your colleagues and ask them to review your syllabus or even observe your classes to facilitate better reflection. It also might be beneficial to reach out to educators who teach different classes or work with students of different levels. By doing so, you might be able to get a wider perspective and, perhaps, find some unexpected solutions.

By writing this reflection, I was able to better understand how my beliefs are formed and reframe my prior assumptions about the importance of teaching grammar as an impetus for professional and personal growth. Additionally, I gained a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between my grammar-teaching beliefs and autonomy. I hope that the reflection and recommendations provided in this article will be helpful for teachers who are struggling with applying autonomous learning alongside more traditional approaches.

Notes on the Contributor

Gutkovskii Aleksandr is an Assistant Lecturer at Toyo University. He is passionate about autonomy, reflective practice, and language advising. In his classes, he tries to encourage autonomous learning and create a safe space for students to achieve their language learning goals.

References

Allen, D. (2016). Japanese cram schools and entrance exam washback. The Asian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 3(1), 54–67. https://caes.hku.hk/ajal/index.php/ajal/article/view/338

Benson, P. (2013). Learner autonomy. TESOL Quarterly, 47(4), 839–843. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.134

Borg, S., & Al-Busaidi, S. (2012). Teachers’ beliefs and practices regarding learner autonomy. ELT Journal, 66, 283–292. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/b459%20ELTRP%20Report%20Busaidi_final.pdf

Borg, S., & Alshumaimeri, Y. (2019). Language learner autonomy in a tertiary context: Teachers’ beliefs and practices. Language Teaching Research, 23(1), 9–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817725759

Farrell, T. S., & Lim, P. C. P. (2005). Conceptions of grammar teaching: A case study of teachers’ beliefs and classroom practices. TESL-EJ, 9(2) https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1065837.pdf

Gibbs, G., & Andrew, C. (2001). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Geography Discipline Network.

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

Li, X. (2023). Developing EFL teachers’ beliefs and practices in relation to learner autonomy through online teacher development workshops. SAGE Open, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231202883

OECD, (2009). Creating effective teaching and learning environments: First results from TALIS. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264068780-en

Osterman, G. L. (2014). Experiences of Japanese university students’ willingness to speak English in class: A multiple case study. SAGE Open, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014543779

Reinders, H. (2020). Fostering autonomy: Helping learners take control. English Teaching, 75(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.15858/engtea.75.2.202006.135

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2018). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

Sakata, H., & Fukuda, S. (2018). Advising language learners in large classes to promote learner autonomy. In C. Ludwig & J. Mynard (Eds.), Autonomy in Language Learning: Advising in Action (pp. 57–81). Candlin & Mynard ePublishing Limited.

Sakui, K. (2004). Wearing two pairs of shoes: Language teaching in Japan. ELT Journal, 58(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/58.2.155

Tripp, D. (2011). Critical incidents in teaching: Developing professional judgement. Routledge.

Appendix

Thank you for this fascinating report on your reflective practice. Teacher autonomy is often considered a necessary prerequisite for the successful promotion of learner autonomy; the fact that you reflect so carefully and insightfully on your own practice and beliefs clearly demonstrates that you are qualified to facilitate the development of your students’ own reflective practice. And as an L2 English speaker, your perfect mastery of written English also demonstrates that you are highly qualified to guide your students in their acquisition of English grammar – certainly more so than most L1 English speakers. It is therefore not difficult to see how you would experience conflicting impulses as to how best to guide your students in their language learning journeys.

Perhaps you can move towards a resolution of this conflict by finding a way to synthesize these two impulses, rather than pitting them against each other? Most language learners would likely agree that both accuracy and fluency are desirable goals. I suspect there must be effective ways to guide students towards grammatical accuracy that do not require a teacher centered, transmission-of-knowledge, teaching-for-the-test approach. I am personally interested in this topic myself, as I have been put in charge of an “English Grammar” course for next year, and have been pondering how best to approach the task. Theories on learner development posit that a given grammatical item will be acquired according to the learner’s internal syllabus and their developmental readiness to acquire that item, rather than the sequence in which it is taught to them. As autonomy facilitators, in terms of grammar, perhaps we can best serve our learners by helping them to develop a capacity for self-awareness and self-evaluation that will guide them in a more organic and self-regulated process of acquiring grammatical accuracy. How to integrate such an approach into a course syllabus and reconcile it with institutional demands for measurable outcomes, however, is the challenge. I look forward to further reports and helpful hints from your own journey as an autonomy supporter!

Dear Henry Foster,

Thank you for your insightful comments. I resonate with your idea that accuracy-based activities can also serve as one of the components for autonomous learning. I have realized that grammar might be a stepping stone for low-level students who begin their journey towards autonomy. Some of my current students are more familiar with grammar-based activities due to their prior high school experience which focused on accuracy. Perhaps, including grammar and awareness-raising activities at the initial stages of autonomous learning might help these students feel more confident engaging in fluency-driven learning activities later on.