Junko Takahashi, Kanda University of International Studies

Takahashi, J. (2025). Guiding growth: Using the wheel of reflection in teacher career development. Relay Journal, 8(1), 27-37. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/080103

[Download paginated PDF version]

Abstract

This paper explores a mentoring session with a returning teacher, in which I took on the role of mentor to encourage professional growth through reflective practice. The session focused on improving the mentee’s self-reflection as a professional by utilizing a visual tool called the Wheel of Reflection. The findings suggest that the various categories within the Wheel are effective for organizing ideas and thoughts. Additionally, relational mentoring not only enhances the mentee’s reflective abilities and future vision but also contributes to the mentor’s professional development, fostering a dynamic and mutually enriching partnership.

Keywords: wheel of reflection, mentoring session, career development

This paper focuses on a one-on-one mentoring session conducted as part of Advisor Educator’s Transformation: Mentoring Others, the fourth course in the Learning Advisor Training Program offered by the Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education (RILAE) at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS). Emphasizing the importance of continuous professional development, the course equips learning advisors with the skills and knowledge needed to train and mentor others. It introduces a range of advising and mentoring strategies and tools, and requires participants to conduct a mentoring session to apply what they have learned. The session discussed in this paper aimed to implement intentional reflective dialogue (IRD; Kato, 2012), using advising strategies to support the mentee’s reflection on her role as an educator.

According to Kato (2022), intentionally structured one-to-one dialogue refers to a purposeful and reflective interaction designed to facilitate deeper self-awareness, goal setting, and transformation in the mentee’s professional thinking and behavior. This process of guided reflection aligns with Thavenius’s (1999) view of the autonomous teacher as someone “who reflects on her teacher role and who can change it, who can help her learners become autonomous, and who is independent enough to let her learners become independent” (p.160).

Mentoring is commonly described as a relationship in which a more experienced mentor supports a less experienced mentee in advancing their career (Kram, 1985). Recent trends in mentoring have moved away from a one-way, hierarchical approach and towards a more relational perspective (Ragins & Verbos, 2007). Relational mentoring emphasizes mutual influence, growth, and learning, rather than viewing the mentor as the sole authority. Both participants in the relationship aim to grow, learn, and contribute to each other’s development (Ragins, 2011). According to Kato and Mynard (2016), mentoring other advisors is the most effective way to develop into an expert advisor. Building on this idea, Kato (2022) explains that high quality mentoring relationships should be intentionally designed to support not only professional growth but also the well-being and intrinsic motivation of both mentor and mentee. Drawing on Relationships Motivation Theory (RMT; Ryan & Deci, 2017), Kato argues that mentoring which allows both individuals to experience autonomy and support each other’s psychological needs helps strengthen the relationship and encourages long-term professional development. In this way, mentoring becomes a reciprocal and empowering process that supports the personal and professional growth of both participants.

Background of My Relationship with the Mentee

Yuka (a pseudonym), is a part-time lecturer at a private university in Japan. After earning her master’s degree, she taught English-related courses at several private universities. She took an eight-year break from her career to focus on raising her children and returned to teaching two years prior to our mentoring session. I have known her for over 10 years, although we have never worked closely together. We occasionally meet for lunch to catch up, and our rapport is well established. Our conversations typically revolve around our children, as we both became first-time mothers around the same time. While we sometimes discuss our teaching experiences and future career plans, these exchanges tend to remain surface-level. As a working mother like her, I was interested in how she views both her future career and her current teaching. For the mentoring session, I invited her to participate in a session, which was conducted in a café and lasted approximately 30 minutes. The session was conducted in Japanese, audio-recorded, and then translated into English for the excerpts. Permission to use the session content for publication was granted by the mentee, Yuka.

The Wheel of Reflection

Kato and Mynard (2016) suggest that cognitive tools, including visual aids, can enhance learning and cognitive growth by encouraging deeper reflection, promoting self-awareness, and facilitating more effective advising. Such tools support learners and educators in visualizing abstract ideas, making connections, and articulating insights about their practice. Yamashita and Kato (2012) further emphasize that structured visual tools are particularly effective in promoting reflective practice, as they help individuals organize thoughts and examine their experiences from multiple angles. They also note that graphical representations, such as visual wheels, can reduce the cognitive burden learners experience during active reflection and decision-making, helping them approach complex ideas more easily.

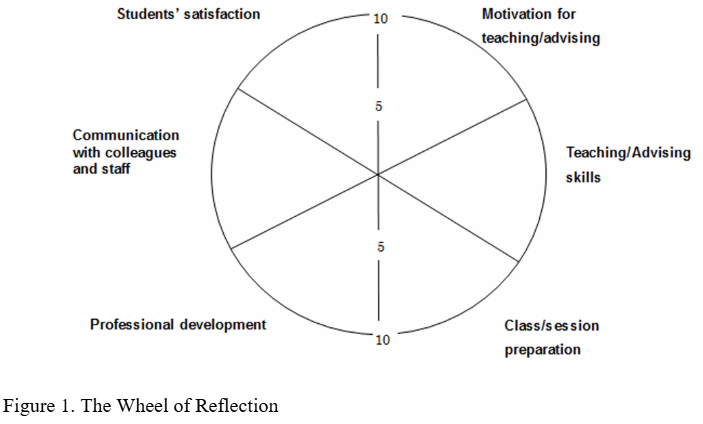

Following the principles above, I incorporated the Wheel of Reflection, a tool introduced and used in the advising course, into the session (see Figure 1). This tool consists of six areas (Motivation for teaching, Teaching skills, Class preparation, Professional development, Communication with colleagues and staff, and Students’ satisfaction), allowing individuals to assess their current satisfaction in each domain on a scale from 0 (center) to 10 (outer edge). The design is inspired by the Wheel of Language Learning (WLL), which was developed to help learners understand the interrelated nature of various learning components (Kato & Mynard, 2016). Alm and Fortin (2024) describe the WLL as an engaging visual tool that supports both metacognitive development and comprehensive reflection during advising sessions. In a similar way, the Wheel of Reflection helps educators recognize the interconnectedness of professional elements and reflect on them holistically. In a mentoring session, Macdonald (2019) observed that using the Wheel of Reflection enabled his advisee to engage in more logical thinking and to recognize how the different areas were interconnected.

During the dialogue, I also applied advising strategies introduced in the Learning Advisor Training Program to facilitate more meaningful reflection. These included strategies such as restating and summarizing, which are intended to help learners gain greater insight into their own thoughts and learning processes (Kato & Mynard, 2016).

The Session

Exploring Challenges and Aspirations in Professional Development

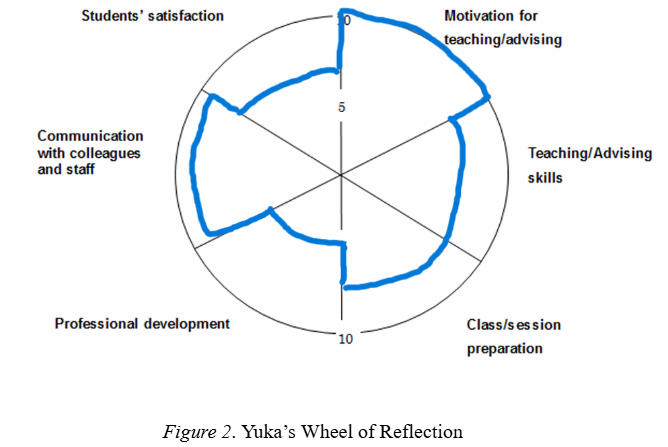

Following Yamashita and Kato (2012), I asked Yuka to rate her current level of satisfaction in each area and explain the reasons behind her self-evaluation (see Figure 2).

She began by talking about the area she rated highest, providing reasons for her score and elaborating on her current experience. As she continued, she reflected on other areas with varying levels of satisfaction.When she reached the “professional development” area, where she gave her lowest score, 5, she first confirmed with me whether her understanding of “professional development” was correct, even though she had already ranked her level. Her definition of professional development was about how much a teacher has developed their skills and knowledge. She admitted that the score for this area was not high, speaking with a slightly sad voice.

Yuka: I review the knowledge I have and teaching methods, activities, and how I teach, and then implement them again in class. I try to make small improvements from there, but I’m not really trying anything new.

Junko: Ah, I see. But, as a key point, you always… after each class, you definitely review and try to apply that to the next time, right?

Yuka: Yes, reflection and trying to find areas for improvement.

Junko: So, when you say you’re not doing anything new, what exactly do you mean by that?

Yuka: It’s like, I don’t know about activities I’ve never seen before, or maybe ones I can’t even think of. Also, the types of activities you would learn as theories in books – for example, I do collaborative learning like CL, so I can use the knowledge I already have and slightly modify it to fit my needs. But other than that, I’m not exploring things I don’t know about. For example, from the conferences I’ve attended, I’ve been out for about 6 or 7 years, so there’s probably new methods or activities that have come up since then. I haven’t really tried to explore or adopt those.

Junko: I see. So, it’s about knowledge? New knowledge?

Yuka: Yes, it’s about knowledge or theories.

Junko: It’s not that you don’t have the knowledge and aren’t applying it, but for you, it’s more about bringing in more and more new knowledge…

Yuka: I’ve been stuck in that regard.

Junko: You’ve been stuck. Is there a particular reason you feel stuck?

I repeated her statement and employed a reflective question to elicit deeper clarification. She articulated two reasons in response, which provided valuable insights for the mentoring process. First, she admitted that she wants to refine her existing materials to a level where she feels satisfied. Second, she mentioned her lack of motivation to try new things, noting that she is not currently attending conferences, giving presentations, or writing papers. She believes that having a clear goal, such as preparing for a JACET presentation, could help reignite her motivation, as she used to actively participate in these activities before becoming a parent.

Rediscovering Professional Identity After Life Change

After the reflective question prompted her to explore the underlying reason for feeling stuck, she began speaking uninterruptedly about how childbirth had transformed her life and how she was navigating her recovery in the context of teaching.

Junko: You used to work toward your goals, but it seems like your life has changed.

Yuka: Yeah, it’s because of the environment.

Yuka: My environment changed, and I ended up forgetting a lot of the knowledge I had learned about collaborative learning and such. After going through childbirth and childcare, I started my return to work by reviewing those things first. I had forgotten so much, and I often found myself thinking, “What was that again?” I had forgotten quite a few technical terms, so before returning to work, I reviewed my old notes and handouts. Now, I feel like I’m finally getting back on track, arranging and adapting what I learned in a way that works for me. But honestly, while doing that, I feel like I also need to acquire new knowledge and perspectives as a teacher.

Junko: So you already have that feeling, right? Over the past three years since you returned to work, you gradually started to remember the things you had forgotten, and now you’ve been able to make use of what you knew before while reflecting on it. So, it sounds like you’re thinking it might be a good time to start incorporating something new, right? Do you have anything specific in mind?

While summarizing her reflections on her teaching journey following childbirth, she provided brief backchannel responses, such as “That’s right” and “Yeah” which helped confirm the accuracy of my summary.

Fostering Motivation and Exploring Practical Steps for Growth

After being prompted to consider new courses of action, she began exploring potential steps she could take.

Yuka: Specifically… Well, one thing I’ve thought about is something you mentioned the other day—going to the JALT conference in Tsukuba. My friend also attended. I think it might be a good idea to start by becoming a member again and getting involved in things like that. If there are conferences, I could go and listen to presentations by other teachers? I’m quite interested in that. I’m curious about how the current educational environment has changed compared to back then. Things have probably changed at universities too. Since there isn’t really a place to share that kind of information at my workplace, I feel like I need to go to broader venues, like conferences, to hear about those things. Doing so might even help boost my motivation a bit? and then I might feel inspired to read more or try new things. Listening to a presentation by another teacher might make me think? For example, “Oh, I’d like to try that for myself,” or “I want to do more of this.” I feel like that might be the quickest path forward.

When responding, she used several positive expressions, such as “I am interested,” “I’m curious,” “It might be a good idea,” “boost my motivation,” and “I feel inspired.” Although she also said, “I need to,” I interpreted it as a positive statement rather than one implying obligation. Her use of “I need to” appeared to reflect her determination to enact change. Notably, after the question whether she had something specific in mind was posed, she began speaking almost immediately and without hesitation. I felt that she had been thinking about the topic vaguely in her daily life, perhaps not in great depth. Her intonation often rose at the end of her sentences, as though she was speaking to herself. This behavior seemed to indicate that she was deeply engaged in the reflective process.

Although she mentioned that she had not tried anything new and lacked a strong desire for learning, her reflections revealed a forward-looking mindset. She appeared to be envisioning her future self and preparing to take steps toward growth. Furthermore, she demonstrated an awareness of how to re-energize her motivation, as evidenced by her ability to articulate a clear strategy: attending a conference to gain new knowledge. I hope that asking her about specific actions encouraged her to explore practical ways to move forward. This interaction may have helped her bridge the gap between reflection and actionable steps, fostering both self-awareness and learner autonomy.

Exploring Learning Preferences and Motivating Action through Reflection

After she said going to a conference is the shortest way to gain new knowledge, I quickly summarized what she talked about to encourage her to talk more about her future vision. She continued to explore ways to take concrete actions, considering her learning style.

Junko: You would like to go there to be inspired…

Yuka: Rather than finding that theory in libraries or online, looking up the papers by the people who wrote it or came up with it, I actually want to go somewhere in person and experience those presentations face-to-face. I want to feel it firsthand. I think that would probably suit me better and be easier to absorb.

Junko: You mean it’s just your style?

Yuka: Exactly. It’s just my personality. And if I don’t understand something on the spot, I can ask questions during the Q&A. That might lead to more interest or even motivation, I think.

Junko: I see. You really seem to know yourself well.

Yuka: Do you think so? I think talking to you right now is helping me digest my feelings.

The excerpt above highlights her proactive, self-aware, and optimistic attitude. She also uses positive words like “I want to,” “interest,” and “motivation.” She understands her learning style and the benefits of attending a conference. She is confident that going to a conference will be the first step in motivating herself and gaining new knowledge. Furthermore, her statement in the previous excerpt, “I think talking to you right now helps me digest my feelings,” highlights the significance of reflection through dialogue. Such reflection can provide greater opportunities for transformative learning, which self-reflection alone may not easily achieve (Kato & Mynard, 2016).

Reflections on the Wheel of Reflection: Insights and Feedback from the Session

Following the session, I asked her about her experience using the Wheel of Reflection. She described it as an effective tool for reflecting on her teaching journey and facilitating the conversation. She particularly appreciated that the wheel encompassed a variety of categories, which she found helpful in organizing her ideas and thoughts. She noted that teaching involves many interconnected aspects, and the structured categories provided by the wheel made it easier for her to articulate and consolidate her reflections. In contrast, she explained that responding to a single, broad question like “How do you feel about your teaching?” would have been overwhelming and left her uncertain about where to begin.

Furthermore, she emphasized the importance of engaging in reflective dialogue. While she found scoring her responses on the wheel valuable, she noted that the process of explaining her thoughts during our discussion led to deeper reflection on her teaching practices. This echoed her earlier statement, “I think talking to you right now helps me digest my feelings.” While reflecting on the use of the Wheel of Reflection, she repeatedly mentioned the phrase “organize my ideas/thoughts,” highlighting the wheel’s effectiveness in helping her clarify and structure her reflections. Her comments reinforced the idea that visual tools like the Wheel of Reflection can make complex experiences easier to process and discuss.

Overall, her feedback suggests that the Wheel of Reflection is a practical and effective tool for facilitating reflective dialogue and fostering a comprehensive understanding of one’s teaching experiences. While Yamashita and Kato (2012) explain that such tools can help learners recognize the interconnections among various elements, I realized that I had not fully drawn out this potential during the session. Specifically, I did not ask a ”metaview” question such as “How is each area connected to the other?”, which is intended to encourage learners to “view the bigger picture and take a more global perspective” (Yamashita & Kato, 2012, p.166). As a result, I believe she may have reflected on each area in isolation, rather than seeing how the areas influence one another.

There was another moment I could have approached differently. When she mentioned the possibility of attending a conference, I missed an opportunity to ask a powerful question, such as, “By when will you take action?” This type of question can “evoke clarity and help learners discover possible courses of action” (Yamashita & Kato, 2012, p.166). Additionally, I was surprised when she gave a high score, nine, for communication with colleagues, yet revealed she had not engaged in such discussions. In hindsight, I should have asked her why she gave that score.

Throughout the session, I observed both her struggles and her desire to change. Her frequent use of phrases like “I used to…” indicated a shift in her mindset and practices. These reflections suggested that she was beginning to take ownership of her professional development and redefine her role. This marked an important step toward becoming a more autonomous teacher, as described by Thavenius (1999). Witnessing her progress was deeply gratifying, as it signified a positive transformation.

During the session, I focused primarily on the mentee and did not pay much attention to my own feelings. However, upon reflection after the session, I realized that I had experienced positive changes myself. Firstly, I felt a sense of personal satisfaction from the session. It was fulfilling to witness her looking toward the future with optimism, and I found great happiness in seeing that progress. Secondly, observing her struggles and her desire for change sparked a desire for change in me as well. Her positive transformation motivated me to improve my own teaching and advance my career. For instance, after the session, I began engaging in collaborative teaching reflection with my colleague to improve my teaching. I also started exploring upcoming conferences to gain new ideas for my classes and to inform future research as part of my professional development. Sharing similar life circumstances, I saw potential for growth in her, which in turn made me recognize that potential within myself. I strongly feel that relational mentoring involves mutual learning, where both individuals have an impact on each other. This experience has reinforced my belief that mentoring is not a one-sided process but a shared journey of growth, inspiration, and mutual empowerment.

Notes on the Contributor

Junko Takahashi is a lecturer at Kanda University of International Studies. She holds an MA in TESOL from Kanda University of International Studies. Her research interests include reflection, learner autonomy, and teacher identity.

References

Alm, A. & Fortin, M. (2024). Spinning the wheel of reflection: Facilitating language learning insights through advising. Relay Journal, 7(2), 83-97. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/070203

Kato, S. (2012). Professional development for learning advisors: Facilitating the intentional reflective dialogue. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(1), 74 –92. https://doi.org/10.37237/030106

Kato, S. (2022). Establishing high-quality relationships through a mentoring programme: Relationships motivation theory. In J. Mynard & S. Shelton-Strong (Eds.), Autonomy support beyond the language learning classroom: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective (pp. 164–182). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788929059-012

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

Kram, K.E. (1985) Mentoring at work: Developmental relationships in organizational life. Scott, Foresman.

MacDonald, E. (2019). Reflection through dialogue: Conducting a mentoring session with a juku colleague using the ‘Wheel of Reflection’ tool. Relay Journal, 2(1), 45-59. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020106

Ragins, B. R. (2011). Relational mentoring: A positive approach to mentoring at work. In K. Cameron & G. Spreitzer (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship (pp. 519–536). Oxford University Press.

Ragins, B.R. & Verbos, A.K. (2007) Positive relationships in action: Relational mentoring and mentoring schemas in the workplace. In J. Dutton, and B.R. Ragins (Eds.) Exploring positive relationships at work: Building a theoretical and research Foundation (pp. 91 –116). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Thavenius, C. (1999). Teacher autonomy for learner autonomy. In D. Crabbe & S. Cotterall (Eds.), Learner autonomy in language learning: Defining the field and effecting change (pp. 159–163). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Yamashita, H., & Kato, S. (2012). The Wheel of Language Learning: A tool to facilitate learner awareness, reflection and action. In J. Mynard & L Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context, (pp.164–169). Longman.

Hi Junko,

It was great to see how your effective use of advising strategies, combined with the use of the Wheel of Reflection tool to facilitate the session, helped your mentee to organise and articulate her thoughts, and also begin looking forward while envisioning her future ideal self and steps she could take to achieve this. It was also clear that your mentee trusted you and felt comfortable sharing her feelings. The quote “I think talking to you right now is helping me digest my feelings” stood out and, as you mentioned, highlighted the value of intentional reflective dialogue.

I could also see your growth as an advisor as through reflecting on the session, you identified what you could have approached differently. One thing you mentioned was asking a powerful question for accountability. Since the session, have you talked to your mentee informally to find out if she took the step she planned (i.e. attending the conference)?

I could also relate to reflective dialogue being a mutually beneficial process for both the mentee and mentor. You noted that in sharing similar life circumstances and seeing her potential for growth, you were also motivated to improve your teaching. I’m curious about the collaborative teaching reflection that you have begun engaging in with your colleague and how you do this. Do you ever find yourself using advising strategies with your colleague when reflecting together?

Your article is a valuable contribution that shows the value of using advising tools to stimulate reflective dialogue, not only with learners, but also with peers!

Dear Ewen,

Thank you very much for your thoughtful and encouraging feedback on my article. I truly appreciate the time you took to read it carefully and to highlight the aspects that resonated with you.

Regarding your question about my mentee, yes, I did have an informal follow-up conversation with her. She has been gradually working toward her goals, taking each step thoughtfully and intentionally. Since our advising session, she has made significant changes in her teaching career, carefully considering her family situation with each decision. I truly respect her ability to prioritize what matters most. Each time I hear an update from her, I feel encouraged and reminded that I, too, have the potential to grow and change.

As for the collaborative teaching reflection with my colleague, I have found that I began to use advising strategies more naturally and intuitively as our sessions progressed. It’s fascinating how seamlessly the advising mindset can transfer to collegial contexts and foster mutual learning. Having a series of consecutive reflective sessions was also valuable, as it allowed us to observe our growth throughout the process.

Thank you again for your kind words and insightful questions. I truly value your perspective and am delighted that you found the article meaningful.

Sincerely,

Junko