Ruth Bickle, Kanda University of International Studies

Abstract

This practice-based paper presents my implementation of a second language (L2) identity-focused classroom activity and offers a critical reflection on the pedagogical insights that emerged. I based this task on a body silhouette activity designed by Dressler (2015), involving students expressing their L2 identity by drawing their own silhouette. While Dressler’s (2015) drawing activity took place with young multilingual learners in Canada, my adaptation of the activity was conducted with learners aged between five and six years old attending an English bilingual kindergarten in Japan. Experiencing this drawing-based task made me start to consider how I should further facilitate the exploration of linguistic identity within an immersive context.

Keywords: body silhouette activity, immersive language learning, L2 identity

While working in immersion-based learning with young learners in Japan, I have also been pursuing a Master’s degree in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) for the past three years. Teaching English as a Second Language (ESL) and studying the principles of language acquisition at a graduate level has brought my attention to the chasmic difference between theoretical learning concepts and real-world teaching practicalities.

The first section of this paper will explore immersive language learning, both as a general concept and as a fundamental component of learning in my teaching context. The second section will focus on my reflections on theoretical concepts learnt undertaking the graduate-level course on Learner Autonomy, which initially inspired the activity described in this paper. The third section will introduce Dressler’s (2015) body silhouette activity, followed by an outline of practice or how I chose to adapt and implement this activity in my own context. The remainder of the paper will detail my reflections on practice, how I think the activity went from my perspective, and, lastly, a future takeaway detailing what possible implications I can draw from this experience for the further exploration of linguistic identity in my teaching context.

Immersive Language Learning: My Context

Immersive language learning, as described by Porter and Castillo (2023), involves the continual use of the second language (L2) throughout the day, not only for instructional purposes but also for meaningful communication, thereby transforming the language from a subject of study into a tool for active engagement.

In this paper, immersion specifically refers to students attending an English-Japanese kindergarten, which constitutes my teaching context. Students, aged between five and six years old, have typically been enrolled in bilingual education for approximately three years and are exposed to English throughout the day, both during formal lessons in subjects such as math, writing, reading, and phonics, and during non-instructional times such as lunch, naptime, and outdoor and indoor play. They are actively encouraged and expected to use English with both native-speaking and Japanese native teachers as well as with their peers. While some students come from Japanese-speaking households and others speak English at home with parents who have moderate to high proficiency, the immersive structure of the program supports the development of basic English skills. As a result, most students are able to function and respond in English within the school context with minimal or no Japanese support.

Reflection on the Concept of L2 Identity

Through the Learner Autonomy course in the Master’s program at KUIS, I came to understand that language learning is not simply the acquisition of knowledge to be evaluated, but rather a complex and dynamic process. From an autonomy perspective, learning involves the learner’s active management of cognitive processes, behaviors, and content, reflecting their capacity to take charge of and direct their own educational trajectory (Benson, 2011). A crucial aspect of fostering learner autonomy is recognizing the role of affective factors, particularly identity, in shaping the learning experience.

L2 identity is defined by Ricento (2005) as not something purely in the student’s mind but rather a “contingent process involving dialectic relations between learners and various worlds they inhabit” (p. 895). The concept of identity being created outside the learner dynamically through interaction may be quite relevant to my teaching context, as I teach within an immersive kindergarten where young children are taught in a group setting. In this paper, the concept of L2 identity refers to the emergent bilingual self within an immersive educational environment. Although my school aims to foster bilingual speakers with dual linguistic identities, from my teaching experience, I feel students may not have sufficient opportunities to explore the affective side of speaking two languages. This lack of emphasis on the affective aspects of language learning may be due to language teaching often being reductively viewed as the passing of knowledge from teacher to student (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 2018).

However, as noted by Norton (1997), language learning cannot be treated as a simple passing of knowledge nor be separated from affective factors as it “is also an investment in the learner’s own social identity” (p. 411). The complex relationship between L2 identity and language learning is partially touched on by Dörnyei (2005): when engaged with the L2, learners may be (sub)consciously measuring and comparing their own performance against an imagined ideal self as a highly proficient L2 speaker. Dörnyei and Ushioda (2009) also note that the enhancement and exploration of students’ ideal L2 selves within the classroom could act as a force for sustained language learning and suggest that teachers can “keep the vision alive” (p. 37) through various activities and tasks.

However, according to Zentner and Renaud (2007), conducting explorations of ideal selves with very young children may not be advisable, as most young learners do not develop a fixed perception of their ideal selves until they reach the age of adolescence. Thus, as my learners are five to six years old, it may be more appropriate to reserve more focused and complex explorations of future L2 identities for when they are more developmentally able to understand and respond to such tasks. Instead, as Dressler (2015) and Soares et al. (2021) state, it may be more prudent to provide young learners with simplified and accessible tasks centered on their here-and-now L2 identities to “begin a dialogue that enhances relationships between teacher and students and among students” (Dressler, 2015, p. 43). Dialogue, in this case, refers simply to teachers and students being able to speak about and reflect on linguistic identity in a school environment (Dressler, 2015; Soares et al., 2021). Opening up a dialogue may be a seemingly small but important step towards providing validation of student L2 identity (Soares et al., 2021). In summary, although L2 identity may be too complex to explore in its entirety within this paper, and although my learners may be developmentally too young to experience the more nuanced aspects of L2 identity as it relates to their future and ideal selves, an initial, more accessible task could be beneficial. Such a task could help me as a teacher gain insight into my students’ current self-perception as L2 speakers. It would also allow the learners, perhaps for the first time, to reflect on becoming L2 speakers of English and Japanese – a complex, time-consuming, and potentially life-altering process.

Practice

Drawing on the theoretical insights, reviewed above, particularly the importance of dialogic reflection in young learners’ identity construction (Dressler, 2015; Soares et al., 2021), I sought to create an activity that would open a safe space for my students to visualize and discuss their linguistic selves. I decided to use the body silhouette activity, applied by Dressler (2015) to explore the linguistic identities of Canadian multilingual learners. This activity was among the activities introduced in the Learner Autonomy course of the MA TESOL program by Dr Yamashita. In this section, I will explain the activity, followed by an overview of how I used it within my own context.

The body silhouette activity

Dressler’s study (2015) aimed to explore the linguistic identities of young learners through a multimodal activity that teachers could use to start a dialogue about how students see themselves as speakers of many languages. Students received a blank body silhouette and were asked to color in areas where they felt their languages were located within themselves. Alongside their drawings, they created a key to indicate which color represented each language. Once the drawings were finished, Dressler video interviewed students individually, asking them, “Tell me about your picture,” to explain their pictures.

Dressler analyzed students’ pictures and verbal explanations through the connected concepts of expertise, affiliation, and inheritance. Expertise, in this case, relates to how much of a language students understand, whereas affiliation refers to how affiliated or emotionally connected a student is to a language (Block, 2014). Inheritance, on the other hand, refers to whether the language is spoken within the student’s family (Dressler, 2015). The body silhouette activity offers students an accessible avenue for discussing bilingualism within the school environment, an act that is particularly valuable as it serves to validate their identities as speakers of multiple languages. Moreover, by observing peers and teachers share their experiences as language learners, students may come to view language acquisition not as a finite process that concludes with fluency, but as a lifelong journey shared by many around them (Dressler, 2015). Notably, I observed that various students who participated in the body silhouette activity expressed strong identification with different languages regardless of their proficiency level, suggesting that the activity may provide a meaningful platform for students to articulate and affirm their linguistic identities with greater confidence.

Implementing the body silhouette activity in my context

I implemented Dressler’s body silhouette activity (2015) with my students using a three-step sequence, which involved explaining the activity with examples (10 minutes), showing students my own completed drawing while prompting them to consider their own linguistic identities (10 minutes), and finally students drawn their own body silhouette (20 to 30 minutes).

Step 1: I showed my students a few examples from Dressler’s study coupled with a brief description of what the individual student drawer stated in response to Dressler’s prompt, “Tell me about your picture”.

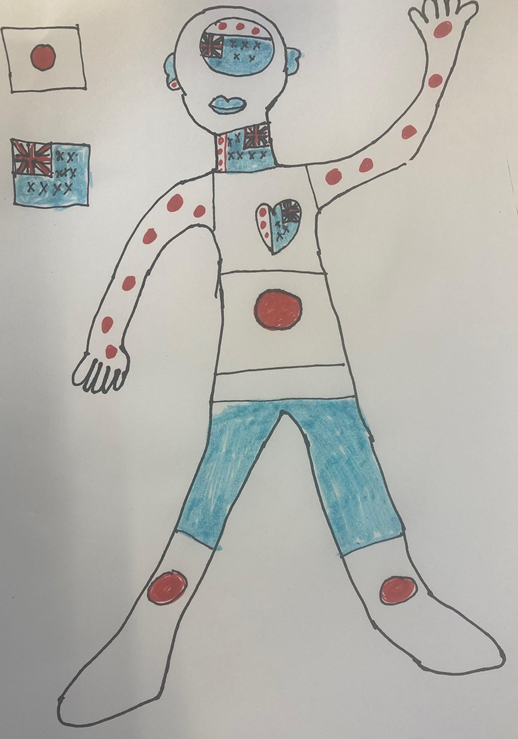

Step 2: I showed students my own completed drawing (see Appendix for I completed body silhouette ), and directed them to use the body shape as a canvas to illustrate their own L2 identity, which I stated, they could later explain verbally to me as I moved around the class.

Step 3: Students began the drawing part of the activity by giving learners a blank drawing of a body as well as crayons, markers, and colored pencils. While conducting the activity, I observed my students’ drawings, listened carefully to their verbal explanations, asked them questions, and took notes. Unlike Dressler, I did not videotape students’ responses or conduct one-to-one interviews.

Reflection

Through reflecting on their drawings and verbal responses, I realized that, when provided with developmentally appropriate and creative materials, even young children can articulate complex and personal perspectives on their emerging linguistic identities. This experience highlighted the potential of such activities to create space for and validate young learners’ self-perceptions as speakers of two or more languages (Dressler, 2015), demonstrating how relatively simple yet imaginative classroom tasks can effectively facilitate meaningful discussions about linguistic identity.

While I agree with Dressler’s (2015) view of the task’s potential to stimulate discussion, my interpretation of its application diverges from her home-language-based focus, largely because my own students, unlike hers, who came from multilingual households, predominantly come from monolingual backgrounds. In my context, students’ home language identities may be particularly strong, since their first language (Japanese) is used across family, school, and society. By contrast, English occupies a far weaker presence and may therefore play a lesser role in their self-perception. Consequently, this activity serves not so much to bring home languages into the classroom, as Dressler (2015) suggests, but rather to foreground the secondary language learned at school as an emerging aspect of learners’ L2 identity. In this sense, the task can help make students’ school-based language learning experiences more visible to themselves, their peers, and the wider educational community.

This activity could be expanded by inviting bilingual teachers at my school to complete their own body silhouettes. Given their advanced language learning experience, this task might prompt them to reflect more deeply on their feelings about themselves as L2 speakers. Such reflection may, in turn, enhance their ability to support and facilitate students’ exploration of their emerging L2 identities within the classroom. Undertaking the body silhouette activity has brought my attention to my potential as a teacher to not only teach students English but also to facilitate in-class reflection on how acquiring this language is shaping their emerging identities.

Notes on the contributor

Ruth Bickle graduated from the MA TESOL Program at Kanda University of International Studies. She has over five years of teaching experience in ESL, mainly with young learners in bilingual contexts.

References

Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching autonomy (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Block, D. (2014). Second language identities. Bloomsbury.

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410613349

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2009). Motivation, language identity and the L2 self. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847691293

Dressler, R. (2015). Exploring linguistic identity in young multilingual learners. TESL Canada Journal, 32(1), 42–52. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v32i1.1198

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation.

Cambridge University Press.

Norton, B. (1997). Language, identity and the ownership of English. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 409–429. https://doi.org/10.2307/358783

Porter, S., & Castillo, M. S. (2023). The effectiveness of immersive language learning: An investigation into English language acquisition in immersion environments versus traditional classroom settings. Research Studies in English Language Teaching and Learning, 1(3), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.62583/rseltl.v1i3.17

Ricento, T. (2005). Considerations of identity in L2 learning. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Soares, C. T., Duarte, J., & Günther-van der Meij, M. (2021). ‘Red is the colour of the heart’: Making young children’s multilingualism visible through language portraits. Language and Education, 35(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2020.1833911

Wenger, E. (2018). A social theory of learning (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Zentner, M., & Renaud, O. (2007). Origins of adolescents’ ideal self: An intergenerational perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), 557–574. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.557

Appendix

The Drawing of my Body Silhouette

(shared with the students – Step 1-3)

Dear Ruth,

I really enjoyed reading this article and found it to be a thoughtful exploration of how theory and classroom practice can meaningfully inform one another. Your experience as a reflective practitioner in a Japanese immersion kindergarten, along with your attention to learner autonomy at the graduate level, makes your paper feel authentic. This openness makes your reflections especially helpful for others in similar roles.

I found your explanation of how you changed Dressler’s (2015) body silhouette activity to be clear and well supported. I think your choice not to use future-focused “ideal L2 self” work with five- to six-year-olds made sense. Referring to Zentner and Renaud (2007) matches your learners’ age and helps show why a “here-and-now” identity talk (Dressler, 2015; Soares et al., 2021) is a good fit in early childhood classrooms.

What stood out to me was the way you reframed language identity in relation to context. By setting multilingual home environments in Canada alongside largely monolingual homes in Japan, you make it very clear that identity-focused activities may function differently across sociolinguistic ecologies. I found your observation that the activity brings school-based L2 identity to the foreground, rather than supporting home-language identity, especially interesting, as it feels like a genuine extension of Dressler’s work rather than a repetition of it. I was also impressed by how your discussion connects with Norton’s (1997) idea of language learning as an investment in social identity, rather than just about language skills. Your description of learners placing themselves in different social and language groups shows the emotional and social challenges of becoming an L2 speaker. I agree that this emotional side is important, but often overlooked in early immersion classrooms.

I found myself really wanting to hear more about what you saw and thought as you looked back on the activity. I kept thinking about what might stand out to you if you tried the activity again later in the year. Would it be a stronger presence of English, changes in where languages are placed, shifts in how children feel about each language, or something else altogether? It made me wonder whether the reflective dimension could be gently extended over time as an ongoing conversation. For example, questions such as “Could it look different another day?”, “Would this color stay the same?”, or “Could a new color appear later or grow bigger?” seem well aligned with your emphasis on fluid, here-and-now identity. I can imagine these kinds of questions helping not only students but also teachers and families see language learning as something lived and changing over time.

Thank you again for sharing your work!