Carol J. Everhard, (Formerly) School of English, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Everhard, C. J. (2018). Re-exploring the relationship between autonomy and assessment in language learning: A literature overview. Relay Journal, 1(1), 6-20. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010102

Download paginated PDF version

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Introduction

The complexities of the relationship between assessment and autonomy in language learning, instead of being addressed, seem to have been quite consistently avoided in the autonomy literature, making research in this area a difficult and often perplexing undertaking. This leads Benson (2015, p. viii) to describe assessment in relation to autonomy as “the elephant in the room that everyone can see, but no one wants to mention.” This is unfortunate, not just for the elephant but for everyone wishing to explore the relationship between assessment and autonomy, however demanding or elusive that might be.

In the past, this has led me to refer to both topics of assessment and autonomy as being akin to secret gardens (Everhard, 2015 pp. 8-9). It would seem that there is too much mystery surrounding these gardens, making teachers afraid to enter, if indeed they can find the way in, find the way to explore the relationship between them, and then to question. Question we must, particularly in areas where the literature is sparse, since there is always the danger of some degree of naivety on the part of researchers or of pedagogical, geographical, cultural, institutional and even political constraints influencing and even tainting findings and outcomes. It is important therefore to dig wide and deep within the literature in order to arrive at some general and ecumenical conclusions.

There are, of course, two sides or aspects to the assessment-autonomy relationship which are of interest to us, the first being the influences or effects of assessment on autonomy and the second being whether it is possible in some way to assess or measure autonomy. In this literature overview, I will endeavour to create research timelines, so that those with an interest in exploring both these aspects, will know where to begin and how far researchers and practitioners in these areas have progressed.

The Influences or Effects of Assessment on Autonomy

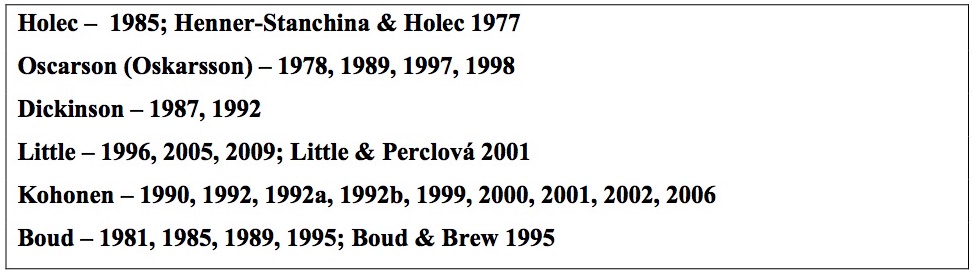

Among the first to mention the assessment-autonomy relationship (see Table 1) are those who were involved with work for the Council of Europe, namely Holec, Oscarson (formerly Oskarsson) and Dickinson. Although Holec (1981) is famous for his definition of autonomy, his work on assessment, and self-assessment in particular, in relation to autonomy, seems to be rarely mentioned, if at all.

Henner-Stanchina and Holec (1977, p. 75) regard evaluation as both an “integral” and “internal” part of learning, going so far as to say that, without it, learning cannot be achieved and that it serves the dual purpose of assessing performance both as a language learner and user. Holec (1985) believes that if a learner is to succeed in changing his/her learning behaviour then he/she has to change their view of the learning process, which may mean going against ideas that may already have been “inculcated” and “the passive role of a consumer of teaching”, to which they have become accustomed (1985, pp. 156-7).

Oscarson (Oskarsson 1978, p. 3) reveals himself as a man of vision, recognising the need for “evaluation techniques which can be put in the hands of the learners”, believing that self-assessment would become “an increasingly important feature of the system”, as it did, consequently, with the European Language Portfolio. Based on research results within Europe, Oscarson (1989, pp. 2-3) concludes that learner judgements can be recognised as valid, justified and bringing greater democracy to pedagogical processes, since the assessment process becomes the “mutual responsibility” (author’s emphasis) of teachers and learners. He (Oscarson, 1989, p. 11) highlights the fact that since learners are unaccustomed to notions of “self-reliance”, they require “practice in autonomous learning and self-directed evaluation, at all levels and in a wide variety of settings” (author’s emphasis).

Oscarson (1997, p. 184) outlines what he sees as three stages of assessment: 1) the Dependent Stage, where there is full dependence on external assessment, which, simply put, means complete reliance on more knowledgeable or authoritative others, rather than the self, which would be internal assessment; 2) the Co-operative Stage, where there is collaborative (internal) self-assessment and external assessment, and finally, 3) the Independent Stage, where there is full reliance on independent self-assessment, which in Henner-Stanchina & Holec’s (1977) terms means assessment has become both integral and internal. Without progression through these stages, Oscarson (1998, p. 2) believes that learning remains at a “superficial” level.

Dickinson (1987; 1992) also places emphasis on self-assessment. He (1987, p. 16) regards the learner’s ability to judge the degree of success of their learning as an “essential” ingredient in achieving autonomy, which he sees as “an attitude towards learning” (1995, p. 165). He also believes that involvement in decision-making “leads to more effective learning”. Self-assessment processes can only be “legitimized” if learners see it as “a valid and useful activity” (1992, p. 35).

He (Dickinson, 1987, p. 150) points to the dangers involved in self-assessment and the fact that learners may “succumb to the temptation to cheat”, which he feels is bound to be high when grades and scores are involved, but he suggests that practice in peer-assessment, using frozen data (1992, p. 35) may be a useful training ground for self-assessment, through learning to assess objectively.

The Council of Europe and the European Portfolio

Gradually, work within the Council of Europe progressed to development of the CEFR scales and the European Language Portfolio (ELP), with Little (2005; 2009) being involved both in Ireland and throughout Europe, with its development and exploitation, while Kohonen (1999, 2000, 2006) was involved within Finland.

Table 1. Timeline for the Literature on the Influence/ Effects of Assessment on Autonomy

Little (2005, pp. 321-322) has examined self-assessment rigorously from many angles, including the theoretical, the practical and philosophical. He sees the main outcomes from self-assessment being three: 1) he believes that for a learner-centred curriculum to make sense, it requires that learners be involved in the process of assessing curriculum outcomes, which includes their own learning achievements; 2) making self-assessment an integral part of assessment processes ensures that it is regarded by teachers and learners as a joint responsibility, but also opens up a wider perspective on learning processes; 3) in order for language learning in the formal context of the classroom to extend to learning from target language use, a learning toolkit that includes self-assessment is essential in order to be able to exploit opportunities for further explicit language learning.

Little (2009, p. 2) sees the CEFR as having the potential “to bring curriculum, pedagogy and assessment into a closer relation to one another than has traditionally been the case”. Like Dickinson, Little (2009, p. 3) recognises that there are particular dangers attached to self-assessment, which include the fact that learners do not necessarily know how to self-assess, or they may overestimate their abilities or they may even resort to cheating and present other people’s material as their own. Nevertheless, Little is convinced that “if ELP-based assessment is central to the language learning process, there is no reason why it should not be accurate, reliable and honest” and he believes very much that self-assessment is “the dynamic that drives reflective language learning”.

Like Dickinson, Little and Perklová (2001, p. 53) regard peer-assessment as a useful springboard for self-assessment and point to the benefits to be drawn from seeing and recognising faults in the work of others, which is easier that seeing our own, but also the benefits to be gained from sharing knowledge and experience which may differ from the other’s. Indeed, Little (1996, p. 31) goes as far as to claim that “classrooms in which self-assessment interacts fruitfully with peer-assessment have probably gone as far as it is possible to go in the promotion of learner autonomy”.

Kohonen (1990, 1992a, 2001), on the other hand, sees autonomy and assessment as being within a framework of what he refers to as “experiential learning” and he also places language learning within the broader notion of “learner education”. He (Kohonen, 2002, pp. 1-2) views language learners and teachers as being members of a “collaborative learning community”, where each can develop fully through “a deliberate shift towards collaborative, active and socially responsible learning in school”. Clearly, he (Kohonen, 1992b, p. 74) sees assessment as playing a major role in developing learner autonomy, so that “a fully autonomous learner is totally responsible for making the decisions, implementing them and assessing the outcomes without any teacher involvement”. In addition to this, he sees affect as having an important role to play (Kohonen, 1992a, p. 23), with the affective component contributing “at least as much as and often more to language learning than the cognitive skills”. Kohonen sees confidence as resulting from competence, with competence resulting from “internalization of the criteria for success”, which is fostered, in turn, by “teaching that encourages the learner’s self-assessment of his or her own learning, both alone and with peers in cooperative learning groups” (Kohonen, 1992a, p. 23).

Kohonen (1992b, p. 83) warns of the contradictions that may run between approaches to teaching and assessment and feels care should be taken so that these are complementary and non-conflictive and thus reinforce authenticity in striving for more learner-centred approaches. Although not all Finnish pupils were enamoured with the ELP, Kohonen (2006, p.18) feels that there was evidence of “involvement”, “engagement” and “ownership” of learning, for the most part, on the part of learners.

Boud’s Views About Assessment and Autonomy

Before moving on to the second question we are concerned with related to assessment and autonomy, namely the idea of assessing or measuring autonomy in some way, we will first look at the work of Boud, who although working and researching beyond the area of SLA, nevertheless offers much that is of relevance to language teaching and learning.

Firstly, Boud would seem to be one of the first academics to recognise the essential link between assessment and the fostering of autonomy and who warned (Boud, 1981, p. 25) that “[p]ostponement of the opportunity to exercise responsibility for learning actively discourages the development of the capacity to do so”.

Boud (1981, p. 25) also sees decision-making as being at the core of autonomy and feels that learner involvement in assessment processes is “crucial”. He asserts that teaching which places the teacher at the centre of activities will never be conducive to autonomy, but equally well, self-assessment must amount to more than simply self-grading. Rather, it must take learners “beyond the present context”, and contribute to learner development through adding to learners’ “self-knowledge” and “self-understanding”, as this can be “emancipatory” (Boud, 1995, p. 20). He sees strong links between reflection and self-assessment and sees self-assessment as necessary for “effective learning” and this, in turn is conducive to lifelong learning. University students who have had this experience are 1) more likely to want to continue their studies; 2) are more likely to know how to do so; 3) are more likely to monitor their performance without recourse to fellow professionals and 4) are more likely to take responsibility for their actions and judgements, he feels.

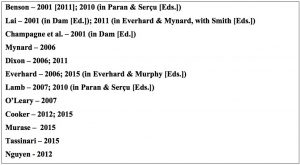

Measuring or Assessing Autonomy

The idea of measuring or assessing autonomy has been one that has attracted interest among teachers and researchers over the years. One of the first references to the idea appears to be by Benson (2001; 2011) in the two editions of his volume ‘Autonomy in Language Learning’ in the Longman/ Pearson series entitled ‘Teaching and Researching’, where he admits that “[f]or the purposes of research and the evaluation of practice, it would be indeed convenient if we had a reliable method of measuring degrees of autonomy” (2001, p. 51). Although Benson (2001, p. 54) accepts that for many reasons measuring autonomy might prove problematic and outlines in detail what he thinks some of those problems are, he still feels that this should not discourage us from attempting to do so.

Benson revisits the idea of measuring autonomy in Paran & Serçu (2010) and again identifies what makes measuring autonomy problematic, stating that “[a]n initial problem in measuring autonomy is determining what autonomy’s necessary or most important observable components are. Autonomy may, of course, have important non-observable components as well…” and Benson feels it is most important that we focus on “the degree to which they [learners] are actually in control of their learning” (Benson, 2010, pp. 78-79). He provides a useful overview of some attempts to measure autonomy, including the study conducted by Lai (2001), which will be mentioned only briefly here.

Lai (2001) is concerned with measuring autonomy in relation to listening skills/ strategies and she creates instruments to measure learners’ autonomy, at both micro and macro levels, based on their ability to set aims and carry out self-assessment. Like Benson, she revisits the subject in 2011 and seems concerned by the fact that there may be different types of autonomy. Her concerns and questions concerning measuring autonomy are summarised and listed in Everhard (2015, p. 29) and a detailed description of what she achieved in her (2001) research is analysed in Dixon (2011) as well as in Benson (2010), mentioned previously.

Interestingly, Champagne et al., in the same (2001) volume as Lai, outline their plans for assessing, both qualitatively and quantitatively, learners’ engagement with autonomy and improvements in their language abilities, with the research being undertaken in three phases. They present an interesting analysis of problematic areas related to assessing language and assessing autonomy, and how both were assessed in relation to their pre-Master’s program Talkbase. Cooker (2012) describes their research as “ground-breaking” because it aims to assess learner autonomy as a separate entity from progress with the language. Even so, the factors which are still of concern to the author-researchers at the end of the research project are summarised in their conclusion, such as the need for self-assessment and “assessment which is an integral part of the program”, but also “pro-autonomy” (2001, p.54).

In 2006, Mynard sets out some of the problems involved in measuring autonomy in the IATEFL LASIG publication, Independence, and lists some of the ways that research on autonomy can be carried out, though admitting that “[a]ttempting to measure the development of autonomous learning in terms of product… is extremely difficult” (Mynard, 2006, p. 3). In turn, in a later issue of the same newsletter, Dixon (2006), whose research is concerned with trying to measure aspects of autonomy, replies to some of her points, creating something of a dialogue on the subject. He asks whether the role of teachers should be “to change students and then to measure what we have done?”

Dixon’s (2011) PhD thesis is a very interesting study which looks at measuring autonomy from every possible angle and uses qualitative and quantitative data from 2 questionnaires to arrive at an understanding of autonomy. By attempting to produce an instrument which would aim to measure autonomy quantitatively, he experiences, for himself, many of the issues which such a task demands. Although he does not succeed in the task he set for himself, he does benefit by coming to a greater understanding of what autonomy is, which he regards as “a long and open-ended process” (2011, p. 331).

Everhard (2006) discusses the elusiveness of autonomy and she also touches on the topic of its measurability and the usefulness of this and commends Mynard’s common-sense approach of recommending that we attempt to “describe and discuss evidence of learner autonomy in a given context” (author’s emphasis, Mynard, 2006, p. 5). Everhard later discusses the assessment-autonomy relationship at some length and also refers to the problems encountered in assessing autonomy (Everhard, 2015).

Table 2. Timeline for the Literature on Assessing/ Measuring Autonomy

O’Leary (2007) describes her attempts to gauge the autonomy of final-year students at Sheffield Hallam engaged in studying French. Using Benson’s three psychological concepts of attention, metacognitive knowledge and reflection, she analyses students’ self-evaluation reports, in the form of portfolios, collected between 1999-2002, Some learner diaries are also used to identify the common approaches which students took. She points to evidence that learners’ assessment of autonomy seems to lead to greater development of autonomy in language learning. She believes that portfolio-based assessment leads to assessment for autonomy, rather than assessment of autonomy (author’s emphasis), using extracts from the portfolios to illustrate her points.

Lamb (2010, pp. 108-109) explores “a method of bringing young learners’ metacognitive knowledge and beliefs about learning to the surface in order to explore ways of enhancing their autonomous behaviours to support assessment for learning”. More specifically, by gathering information from learners’ “metacognitive knowledge”, whether it be person knowledge, task knowledge or strategic knowledge (Flavell, 1985, cited in Lamb, 2010, p. 99), he is concerned about “shifting the focus away from motivating our learners to finding ways of helping them to motivate themselves” (Lamb, 2010, p. 102). The research is thus concerned not so much with trying to assess or measure autonomy, but rather with exploring both the learners’ metacognitive knowledge, as well as their beliefs about learning “with a focus on specific motivational beliefs relating to control and responsibility”. Through small group discussions, which follow particular protocols, Lamb (2010, p. 102) finds a way to help young learners “describe and reflect on aspects of their autonomy”. From the data collected, four clear groups of learners emerged which Lamb (2010, pp. 105-108) chose to describe as ‘The grafters’, ‘The angry victims’, ‘The sophisticates’ and ‘The frustrated’.

Through learners’ revelations, Lamb (2007; 2010, p. 110) comes to recognise the importance of 1) sharing learning objectives with learners; 2) helping learners to recognise the autonomous behaviours they are aiming for; 3) involving learners in peer- and self-assessment of learning; 4) providing feedback that helps learners recognise their next steps and how to take them; 5) promoting confidence that every learner can improve and become increasingly autonomous and 6) involving both teachers and learners in reviewing and reflecting on assessment for autonomy information).

Nguyen (2012) conducts a 3-phase study in Vietnam, in which the researcher claims to apply three principles in what is described as the ‘rigorous’ measurement of autonomy. Firstly, Nguyen establishes what the researcher sees as a clear definition of autonomy which is examined from different perspectives, using both qualitative and quantitative methods to gather data, and research instruments which are constantly refined and extended to provide the gathering of what the researcher sees as rich and informative data.

This particular researcher could be regarded as somewhat unconventional since in Phase One of the research, the researcher aims to prove a connection between gains in learner autonomy and language proficiency, a link which is generally disputed (e.g. Kumaravadivelu, 2003) by experts in the field. In addition, not enough support is provided concerning the researcher’s reductionist approach to defining autonomy, limiting it to the two characteristics of ‘self-initiation’ and ‘self-regulation’, a position which does not appear to have been taken by other SLA researchers, though, interestingly, Deci et al. (1991, p. 323), cited in Lamb (2010, p.100), do regard autonomy as being concerned with “self-initiating and self-regulating of one’s own actions”. If this is indeed the source of the definition, failing to cite it is a serious oversight on Nguyen’s part.

While this researcher seems to have thoroughly examined the autonomy literature before embarking on the research and states that “[t]he main purpose of this study was to explore aspects of learner autonomy demonstrated by Vietnamese students at a university in Vietnam and to find an appropriate approach to promoting it”, due to insufficient information being given, one is led to wonder if these two elements were not somehow approached in the wrong order?

Finally, little information is provided about the strategy training, referred to as ‘metacognitive training’, that was implemented in Phase Two of the research. Even if this amounts more to assessment of metacognition than training proper, Lamb (2007; 2010) would agree that the information that can be gleaned from learners is of great significance. Clearly, we have to look elsewhere for more information about Nguyen’s research and how exactly it was undertaken and why certain choices were made.

Murase (2015), on the other hand, describes how she purposely chose to reconceptualise autonomy, using Oxford’s (2003) expanded model of Benson’s (1997) version of autonomy in order to investigate the nature of autonomy and attempt to measure it, taking into account its multidimensionality. This means that Benson’s original three dimensions: technical, psychological and political-philosophical are extended to include a fourth dimension, namely, socio-cultural autonomy.

Murase examines these dimensions and their sub-dimensions based on the data she gathers. She devises a questionnaire, which is used in its pilot version with 90 first-year students, majoring in English, at Japanese universities. It was tested for its reliability and also to investigate the characteristics of autonomy. In its redrafted version, the Measuring Instrument for Language Learner Autonomy (MILLA), with a total of 113 items, each on a 5-point Likert scale, is used with 1517 students, attending 18 different Japanese universities.

While Murase’s investigation stops short of her original intention which was the desire to be able to gauge individual students’ autonomy, nevertheless it does take into account learners’ attitudes, beliefs and perceived behaviours concerning autonomy in language learning in a holistic manner. Murase’s future investigations might combine MILLA with a more personalised learner autonomy profile.

Like Murase, Tassinari (2015) also chooses to reconceptualise autonomy by scanning the existing autonomy literature. She admits that the assessment or measurement of autonomy “is a very complex question to tackle” (2015, p. 66) and that “in order to investigate the construct of LA appropriately, researchers need to find research methods and assessment tools which are both reliable and valid from the perspective of learning psychology, as well as user-friendly in language learning and teaching contexts” (2015, p. 67).

According to Tassinari (2015, p. 70), approaches to the assessment or measurement of autonomy will depend on: 1) the way in which autonomy is conceptualised; 2) the context in which the learning and/ or teaching takes place, and 3) whether quantitative or qualitative research methods are used, or some kind of combination of the two.

Like Murase, taking into account its multidimensionality, Tassinari (2015, p. 73) arrives at what she describes as “a systematic and operational definition of LA” and develops a dynamic model which takes into account learners’ competencies and skills. Both the model and the descriptors were tested for suitability and the model was subsequently “integrated into the learning advising service at the CILL of Freie Universität” (2015, p. 84) and involves learners in 5 steps (2015, pp. 85-87).

Tassinari describes the model as being “both structurally and functionally dynamic” (author’s emphasis – Tassinari, 2015, p. 75) and feels it is “its dynamic and recursive nature, which makes it particularly suitable for assessing LA in its ongoing development” (2015, p. 88), making it both reiterative and sustainable.

Sustainable assessment of autonomy is what is highlighted by Cooker (2015) in the same volume and based on her study of the autonomy literature, she has arrived at seven learner autonomy categories in her full model of learner autonomy (2015, p. 94), namely: 1) Learner control, within which she has 12 learner autonomy elements; 2) Metacognitive awareness, within which she has eight LA elements; 3) Critical reflection, within which she has three LA elements; 4) Motivation, within which she has three elements; 5) Learning range, where she has four elements; 6) Confidence, where there are two elements and 7) Information literacy, where she has one element.

For her research, 30 subjects were involved in total, with ten of these based in Hong Kong, ten based in Japan and ten based in the UK and of these subjects, 20 were female and ten male. Subjects were given cards to sort into categories within a grid, arranging the cards according to how closely they aligned with descriptions of themselves as learners, ranging from most like me to least like me. The groupings of the cards were then analysed by Q-analysis, which was then able to categorise the learners according to six modes of autonomy, which were: 1) A love of languages; 2) Oozing confidence; 3) Socially oriented and enthusiastic; 4) Love of language learning; 5) Teacher-focused and 6) Competitively driven Cooker, 2015, pp. 97-98).

In her self-assessment tool which follows on from the card-sorting, Cooker avoids naming the above modes of learning, so that the assessment will be non-prescriptive and non-deterministic and so that the tool also permits overlap between modes. Cooker sees engagement with the criteria for assessment, by learners creating their own assessment plans, as something which will be repeated at “periodic intervals” so that it is both “cyclical” and “iterative” and simply a “starting-point for thinking about developing autonomy” (Cooker, 2015, p. 103). An additional advantage of the tool is that it can be used either by students themselves or by learning advisors (p. 104) with the students. In this sense, the instrument used in this research shares a lot in common with Tassinari’s instrument and the use of Q-methodology offers a refreshingly different approach to involving learners in assessment of their autonomy.

Conclusion

In this overview, we considered the two sides to the assessment-autonomy relationship and we looked very briefly along time-lines of thinking and research that has been done in relation to these two different, but, at the same time, related aspects of the effects or influences of assessment on autonomy, on the one hand, and possible and actual attempts to assess or measure autonomy, in some way, on the other. One can only hope that more teachers and researchers will turn their attention to these matters and that in the future more clarity than murkiness and more perspicacity than fogginess will preside.

Notes on the Contributor

Carol J. Everhard has taught EFL/EAP in Greece and the UK. She has a particular interest in learner autonomy, self-access language learning and in the relationship between assessment and autonomy in language learning. Her PhD, completed in 2012, examined the use of triangulated-teacher, peer and self-assessment in promoting autonomy. She co-edited a book, entitled ‘Assessment and Autonomy in Language Learning’, with Linda Murphy, which was published with Palgrave Macmillan.

References

Benson, P. (1997). The philosophy and politics of learner autonomy. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 18-34). New York, NY: Addison Wesley Longman.

Benson, P. (2001). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Benson, P. (2010). Measuring autonomy: Should we put our ability to the test? In A. Paran & L. Serçu (Eds.), Testing the untestable in language education (pp. 77-97). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning (2nd ed.). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Benson, P. (2015). Foreword. In C. J. Everhard & L. Murphy (Eds.), Assessment and autonomy in language learning (pp. viii-xi). Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Boud, D. (1981). Toward student responsibility for learning. In D. Boud (Ed.), Developing student autonomy in learning (pp. 21-37). London, UK: Kogan Page.

Boud, D. (1995). Enhancing learning through self assessment. London, UK: RoutledgeFalmer.

Champagne, M.F., Clayton, T., Dimmitt, N., Laszewski, M., Savage, W., Shaw, J., Stroupe, R., Thein, M. M., & Walter, P. (2001). The assessment of learner autonomy and language learning. AILA Review, 15, 45-55.

Cooker, L. (2012). Formative (self-)assessment as autonomous language learning. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Nottingham, UK.

Cooker, L. (2015). Assessment as learner autonomy. In C. J. Everhard & L. Murphy (Eds.), Assessment and autonomy in language learning (pp. 89-113). Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Deci, E. L., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. Educational Psychologist 26(3&4), 325–346.

Dickinson, L. (1987). Self-instruction in language learning. Cambridge, UK.: Cambridge University Press.

Dickinson, L. (1992). Learner autonomy, 2: Learner training for language learning. Dublin, Ireland: Authentik.

Dickinson, L. (1995). Autonomy and motivation: A literature review. System, 23(2), 165-174.

Dixon, D. (2006). Measuring learner autonomy: A response to Jo Mynard. Independence, Newsletter of the IATEFL LA Special Interest Group, 38, 13-14.

Dixon, D. (2011). Measuring language learner autonomy in tertiary-level learners of English. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Warwick, UK.

Everhard, C. J. (2006). The elusiveness of autonomy. Independence, Newsletter of the IATEFL Learner Autonomy Special Interest Group, 38, 9-12.

Everhard, C. J. (2015). The assessment-autonomy relationship. In C. J. Everhard & L. Murphy (Eds.), Assessment and autonomy in language learning (pp. 8-34). Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Everhard, C. J., & Murphy, L. (Eds.) (2015). Assessment and autonomy in language learning. Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Flavell, J.H. (1985). Cognitive development (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Henner-Stanchina, C., & Holec, H. (1977). Evaluation in an autonomous learning scheme. Mélanges Pédagogiques, CRAPEL, 71-84.

Holec, H. (1981). Autonomy and foreign language learning. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press for Council of Europe.

Holec, H. (1985). Self-assessment. In R. J. Mason (Ed.), Self-directed learning and self-access in Australia: From practice to theory (pp. 141-158). Melbourne: Council of Adult Education.

Kohonen, V. (1990). Towards experiential learning in elementary foreign language education. In R. Duda & P. Riley (Eds.), Learning styles (pp. 21- 42). Nancy: Presses Universitaires de Nancy.

Kohonen, V. (1992a). Experiential language learning: Second language learning as cooperative learner education. In D. Nunan (Ed.), Collaborative language learning and teaching (pp. 14-39). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kohonen, V. (1992b). Foreign language learning as learner education: facilitating self-direction in language learning. In Council of Europe transparency and coherence in language learning in Europe: Objectives, evaluation, certification (pp. 71-87). Report on the Rüschlikon Symposium Council for Cultural Cooperation. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Kohonen, V. (1999). Authentic assessment in affective foreign language education. In J. Arnold (Ed.), Affect in language learning (pp. 279-294). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kohonen, V. (2000). Student reflection in portfolio assessment: Making language learning more visible: Visible and invisible outcomes in language learning. Babylonia 2000, 1-6. Retrieved October 12, 2008 from http://www.uta.fi/laitokset/okl/tokl/projektit/eks/pdf/babylonia100.pdf

Kohonen, V. (2001). Towards experiential foreign language education. In V. Kohonen, R. Jaatinen, P. Kaikkonen, & J. Lehtovaara (Eds.), Experiential learning in foreign language education (pp. 8-60). Harlow, Essex: Pearson Education Ltd.

Kohonen, V. (2002, March). Student autonomy and the teacher’s professional growth: Fostering collegial culture in language teacher education. Paper presented at Symposium on Learner Autonomy, Trinity College, Dublin. Retrieved June 4, 2009, from http://www.script.activino/portfolio/kohonen_student_autonomy.pdf

Kohonen, V. (2006). On the notions of the language learner, student and language user in FL education: building the road as we travel. In P.Pietilӓ, P. Lintunen & H.-M. Jӓrvinen (Eds.), Kielenoppoja tӓnӓӓn – Language learners of today (pp. 37-66). [AfinLA Yearbook 2006/No 64]. Jyvӓsklӓ: AfinLA.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2003). Beyond methods: Macrostrategies for language teaching. London, UK: Yale University Press.

Lai, J. (2001). Towards an analytic approach to assessing learner autonomy. In L. Dam (Ed.), Learner autonomy: New insights: AILA Review, 15 (pp.34-44).

Lai, J. (2011). The challenge of assessing learner autonomy analytically. In C. J. Everhard & J. Mynard, with R. Smith (Eds.). Autonomy in language learning: Opening a can of worms (pp. 43-49). Canterbury, UK: IATEFL. (e-book.)

Lamb, T. (2007). From assessment for learning to assessment for autonomy? Evaluating autonomy for formative purposes. Plenary presentation, IATEFL LASIG University of Warwick Conference, May 2007.

Lamb, T. (2010). Assessment of autonomy or assessment for autonomy? Evaluating learner autonomy for formative purposes. In A. Paran & L. Serçu (Eds.), Testing the untestable in foreign language education (pp. 98-119). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Little, D. (1996). Strategic competence considered in relation to strategic control of the language learning process. In H. Holec, D. Little, & R. Richterich, Strategies in language learning and use (pp. 9-37). Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Little, D. (2005). The Common European Framework and the European Language Portfolio: Involving learners and their judgements in the assessment process. Language Testing, 22(3), 321-336.

Little, D. (2009). The European Language Portfolio: Where pedagogy and assessment meet. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe.

Little, D., & Perclová, R. (2001). The European Language Portfolio: A guide for teachers and teacher trainers. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe.

Murase, F. (2015). Measuring language learner autonomy: Problems and possibilities. In C.J. Everhard & L. Murphy (Eds.), Assessment and autonomy in language learning (pp. 35-63). Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mynard, J. (2006). Measuring learner autonomy: Can it be done? Independence, Newsletter of the IATEFL Learner Autonomy Special Interest Group, 37, 3-6.

Nguyen, L. T. C. (2012). Learner autonomy in language learning: How to measure it rigorously. New Zealand Studies in Applied Linguistics, 18(1), 50-65.

O’Leary, C. (2007). Should learner autonomy be assessed? Proceedings of the Independent Learning Association 2007 Japan Conference: Exploring theory, enhancing practice: Autonomy across the disciplines. Kanda University of International Studies, Chiba, Japan, October 2007.

Oscarson, M. (1989). Self-assessment of language proficiency: Rationale and applications. Language Testing, 6(1), 1-13.

Oscarson, M. (1997). Self-assessment of foreign and second language proficiency. In C. Clapham & D. Corson (Eds.) Encyclopedia of language and education, Vol. 7: Language testing and assessment (pp. 175-187). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Oscarson, M. (1998). Learner self-assessment of language skills: A review of some of the issues: IATEFL Special Interest Group Symposium, Gdansk, Poland. 18-20 September, 1998.

Oskarsson, M. (1978). Approaches to self-assessment in foreign language learning. Oxford: Pergamon Press for Council of Europe.

Oxford, R. L. (2003). Toward a more systematic model of L2 learner autonomy. In D. Palfreyman & R.C. Smith (Eds.), Learner autonomy across cultures: Language education perspectives (pp. 75-91). Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tassinari, M. G. (2015). Assessing learner autonomy: A dynamic model. In C. J. Everhard & L. Murphy (Eds.), Assessment and autonomy in language learning (pp. 64-88). Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dear Dr. Everhard,

Greetings from Japan! I am currently doing a doctoral program, and as a unit assignment, I recently decided to revisit various theoretical frameworks of learner autonomy and examining how learner autonomy education is implemented in my research context. Thank you for providing a comprehensive overview of assessment of learner autonomy in this article and publishing this at perfect timing 🙂 ! I have been keen on this field as my profession is advising in language learning, which allows me to work with individual students closely in advising session; thus, I have plentiful opportunities to witness learners’ transformation to become autonomous learners in everyday practice. At the same time, I often face the dilemma when it comes to assessment. I have been re-reading Benson (2001), and echoing his statement “the essence of genuinely autonomous behaviour is that it is self-initiated rather than generated in response to a task in which the observed behaviours are either explicitly or implicitly required.” (Benson, 2001, p. 52). As many researchers agree, learner autonomy is a multifaceted construct and it is indeed difficult to be defined universally. I like your metaphor of “secret garden” (Everhard, 2015, pp. 8-9)! Yes, I must confess I have been avoiding to touch the area because of the complexity of learner autonomy! This article encouraged me to enter this secret garden with a wide range of literature in learner autonomy.

Here are some comments/questions I have;

Learner autonomy consists of, as the major models of learner autonomy suggest, different aspects. I also believe the notion of learner autonomy varies depending on cultural contexts. For example, the work by Littlewood (1999) presents the distinction between proactive autonomy and reactive autonomy. In my teaching/advising context, the majority of learners have been through Japanese educational system; on the other hand, the majority of their English teachers come from western countries. Is it possible to have a mutual model of learner autonomy assessment in this kind of teaching context? This is something I have been thinking a lot these days.

You introduced various articles that would help me investigate methodologies of learner autonomy assessment. I am interested in Murase’s (2015) questionnaire design as I have not approached to quantitatively measuring learner autonomy. It is intriguing to see how socio-cultural autonomy can be quantified as I believe it is not measurable (yet it depends on how researchers define socio-cultural autonomy itself). Do you have any suggestions on this point? Sociocultural aspects of language learning, I think, involves learner identity construction, significant change in learner belief, or interpersonal relationship to a certain extent. What is the possible methodology of assessing/measuring these aspects (or should we measure…?)

I hope my comments read well-thank you again for this article! I will definitely come back to it multiple times when writing a literature review for my assignment. I look forward to your response.

References

Benson, P. (2001). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Everhard, C. J. (2015). The assessment-autonomy relationship. In C. J. Everhard & L. Murphy (Eds.), Assessment and autonomy in language learning. Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Littlewood, W. (1999). Defining and developing autonomy in East Asian contexts. Applied Linguistics, 20(1), 71-94.

Murase, F. (2015). Measuring language learner autonomy: Problems and possibilities. In C.J. Everhard & L. Murphy (Eds.), Assessment and autonomy in language learning. Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dear Kie,

Thank-you for your positive comments. Your work as an advisor sounds very interesting and if you are able to see learners being transformed, then I am sure that you are already encouraging them to be autonomous, more than you realise. I agree that autonomy is a very complex matter and demands a great deal of time and patience on the part of the teacher/advisor, but that it brings its own rewards.

As for your comments/ questions, I agree that Littlewood’s (1999) distinction between proactive and reactive autonomy is useful and these seem to equate with Smith’s (2002) ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ versions of autonomy and with Kumaravadivelu’s (2003) ‘liberatory’ and ‘academic’ versions of autonomy. Since it is generally agreed that autonomy is not something fixed or static, we should expect it to be in a permanent state of flux.

Concerning a model of autonomy which can accommodate different approaches to learning and teaching, I can only speak from my own experience. Although I had been using peer-assessment for many years with my learners in higher education, it was due to the research interests of a colleague that I became involved in self-assessment and I found the idea quite novel and interesting. Not all of my colleagues involved in this project shared this enthusiasm and those that were of the ‘old school’ were quite vociferous in their objections, as were a number of students, initially. Neither believed that learners should have so much assessment power bestowed upon them. Years of conditioning by ‘the system’ had resulted in a fixed mind-set, which made them resistant to change, whatever positive benefits such change might bring.

For the purposes of my research, I adapted an existing model of lifelong learning for engineers (Stolk, Martello & Geddes 2007) to that of autonomy in language learning. This adaptation helps to show that the degree of autonomy that can be enjoyed by learners increases according to the degree of involvement of the self in the assessment process. Accordingly, this model (see Everhard 2014:39 in Burkert, Dam & Ludwig 2014) accommodates all styles of teaching and learning and shows the factors that influence how progression towards autonomy can be achieved. You might find that this model helps illustrate the thinking of Littlewood, Smith and Kumaravadivelu.

Regarding your points concerning socio-cultural autonomy and its measurement, unfortunately this goes beyond the realms of my own research. The 1st year students I encountered in my university classes had evolved due to exam pressure as skilled learning machines, but unfortunately the skill-set they had acquired did not include much in terms of critical thinking skills.

I used simple questionnaires of a psycho/socio-cultural nature in order to first of all raise awareness of themselves as people and then progressed to other questionnaires which would help them examine their beliefs and better understand themselves as learners. Later, when they had been through the triangulated assessment process, I used questionnaires once again to gather information about their attitudes towards peer- and self-assessment.

Since Dr Fumiko Murase’s questionnaire and her statistical methodology for measuring the socio-cultural aspects of autonomy are quite complex, I believe that the best approach would be to address your questions directly to Dr Murase herself. I am sure she would be happy to help.

I wish you continued success with your work and hope you will enjoy exploring further what the assessment-autonomy relationship has to offer.

Best regards,

Carol