Authors

Amelia Yarwood, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan

Andria Lorentzen, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan

Alecia Wallingford, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan

Isra Wongsarnpigoon, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan

Research Team Members: Emma Asta, Andy Gill, Yuri Imamura, Michelle Lees, Andria Lorentzen, Jo Mynard, Arthur Nguyen, Scott Shelton-Strong, Alecia Wallingford, Isra Wongsarnpigoon, and Amelia Yarwood.

Yarwood, A., Lorentzen, A., Wallingford, A., & Wongsarnpigoon, I. (2019). Exploring basic psychological needs in a language learning center. Part 2: The autonomy-supportive nature and limitations of a SALC. Relay Journal, 2(1), 236-250. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020128

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

Basic Psychological Needs Theory (BPNT) is one of several mini theories within Self-Determination Theory, a framework developed by Deci and Ryan’s (1985) to study human motivation. As part of a larger, on-going project, the three main components of BPNT, autonomy, relatedness and competence, are used as points of evaluation to determine the autonomy-supportiveness of a Japanese self-access learning center (SALC). Based on the analysis of 107 interviews, we will highlight how the SALC is structured to be an autonomy-supportive environment. Additionally, we will provide insight into the importance of relatedness to the learners of our SALC and explore the contractions between their desire to communicate in English and their reluctance to actualize their desires. Based on these findings, future interventions will be discussed to outline actions the SALC can take in order to further develop the autonomy-supportive nature of the self-access environment.

Keywords: Self-determination theory, self-access center, autonomy, interventions

Context of the Research

This study was conducted in a Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) located at a Japanese university dedicated to the teaching of foreign languages. The SALC itself has undergone numerous changes in terms of size, location, and language policy. Initially, the SALC was an English-only space designed to be as immersive as possible. However, despite the immersive intentions of SALCs, not all students will opt in as a result of various sociocultural, motivational, and logistical factors (Gillies, 2010) such as lack of familiarity with native-speaking teachers or a disconnect between how they view the usefulness of the SALC in relation to the more structured classroom environment (Gillies, 2010). Following the move to an intentionally designed, self-access space which offered a spacious, modern feel, and additional floor, the language policy changed. While the second floor remained an English-only environment, on the first floor, a flexible language policy that encouraged multilingual usage was adopted. Despite the two language policies having been designed to accommodate the varying needs of the students, the dual policy system has not yet been adopted by the entire student body (Imamura, 2018). Developing environments that are immersive and inclusive and that reflect an evidence-based understanding of language learning is by no means an easy task, especially when the students inhabiting those spaces might not be aware of best practice. As such, for self-access centers to be considered effective, they need to develop policies, practices, and spaces where students feel encouraged and supported to learn languages rather than simply viewing the spaces as convenient locations for other work (Sturtridge, 1997) or for conversing in their native languages. This support requires not only continuous personal interactions between staff and students to take place, but also the development of language awareness and learner awareness programs and materials (Sturtridge, 1997; Curry, Mynard & Watkins, 2017; Hobbs & Dofs, 2017; Mynard & Stevenson, 2017). At our SALC, we take this to imply that our environment should be “empowering learners to engage in reflective practice and take charge of their language learning” (SALC Mission Statement, 2017) by increasing learners’ opportunities for interdependence and interaction with others and engaging in structured practices that guide their understanding of learning processes.

Autonomy-Supportive Environments

Autonomy-supportive environments in our view are characterized by the presence of policies, practices, and spaces that enhance students’ ability to construct their own process of learning a language rather than controlling said processes. The presence of policies and structured practices in particular may seem an antithesis to autonomy if autonomy is understood as unbridled freedom. However, it could be argued that unbridled freedom is not autonomy (For a detailed discussion of the issue, see Ryan, 1993). Autonomy and structure are not antithetical but rather joint facilitators that can promote greater wellbeing in terms of motivation, engagement, and learning (Grolnick & Ryan, 1987; Jang & Reeve, 2005; Sierens, Vansteenkiste, Goossens, Soenens, & Dochy, 2009). To illustrate: one of the aims of the study conducted by Sierens, Vansteenkiste, Goossens, Soenens, and Dochy (2009) was to explore the connection between autonomy-support and structure as key components of motivational teaching practices. Five hundred twenty-six Belgium adolescents in their final two years of schooling were presented with questionnaires comprised of factors relating to both their teacher’s teaching style (autonomy-support and structure) and their own self-regulated learning (SRL) behaviours. The results lead the authors to suggest that both structure and autonomy-support are necessary in that “their simultaneous presence works in a synergistic fashion to facilitate SRL” (Sierens et al., 2009, p. 66). Structure without autonomy-support may devolve into controlling practices, but it appears that with a degree of autonomy-support, structure provides learners with the framework from within which they are able to control their own learning processes.

Basic Psychological Needs Theory

With the goal of exploring and further developing an autonomy-supportive environment, the research team utilized the Basic Psychological Needs Theory (BPNT) component from within Deci and Ryan’s Self-Determination Theory (1985) as a framework in the present study. BPNT serves as a viable framework for explorations into the autonomy-supportive environment of a SALC due to its focus on providing an understanding of how social forces and interpersonal environments affect autonomous behaviours (Deci & Ryan, 2008) of individuals and groups. Furthermore, the theory has been tested in multiple cultural contexts which has lead the authors to conclude that “feelings of autonomy, like competence and relatedness, are essential for optimal functioning in a broad range of highly varied cultures” (Deci & Ryan, 2008, p.183). The autonomy, competence, and relatedness factors mentioned by Deci and Ryan here are considered the core components of BPNT and require a brief overview (See Asta & Mynard, 2018 for an overview of SDT and BPNT-based research in SALCs).

Autonomy as defined by Deci and Ryan (2000, p.252) is “to self-organize and regulate one’s own behavior (and avoid heteronomous control), which includes the tendency to work towards inner coherence and integration among regulatory demands and goals.” The reference to “inner coherence and integration” (Deci & Ryan, 2000, p.252) argues that while outside forces may influence an individual’s actions, if reflectively that individual supports and consents to the action, then it will be considered autonomous (Ryan & Deci, 2008; Deci & Ryan, 2016). In the case of a student being told to use a certain textbook for examination preparation, autonomy would be achieved if the student reflects on the usefulness of the textbook and determines that it would be in their best self-interest to comply with its use.

Competence relates to the opportunities individuals have to engage in challenges and to experience mastery when negotiating their physical and social environments (Deci & Ryan, 2000). For example, students may have a greater sense of competence in environments that provide scaffolding since scaffolding is the act of providing temporary assistance to help learners to develop new understandings so that they are later capable of completing similar tasks individually (Hammond, 2002).

Relatedness refers to the close emotional bonds that generate feelings of connectedness and belonging with others in our communities (Ryan & Deci, 2008), including peers, teachers, and family. Relatedness is presented as being strongly connected to autonomy (Ryan, Deci & Grolnick, 1995) in that the extent by which individuals feel free to be their authentic self with others is also reflected in their sense of their autonomy being supported. In other words, students who feel connected to a teacher may internalize the achievement-related values shared by that teacher and engage in achievement-focused behaviors.

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to explore the extent to which the SALC and its environment is autonomy-supportive as well as the ways in which it meets the needs expressed by our learners. In cases where a need appears unsupported, interventions are suggested.

Method

Participants

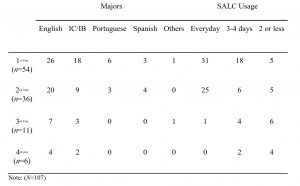

Being the primary stakeholders in the continued effectiveness and evolution of the SALC, the sample population was comprised of currently enrolled students. Table 1 shows the breakdown of the students involved in the present study.

Table 1. Participant Details

First- and second-year students comprised the majority of the sampled population, most likely due to their schedules. Compulsory English language classes are requirements for first- and second-year students, while third- and fourth-years frequently take fewer elective classes or focus their energies on job-hunting.

First- and second-year students comprised the majority of the sampled population, most likely due to their schedules. Compulsory English language classes are requirements for first- and second-year students, while third- and fourth-years frequently take fewer elective classes or focus their energies on job-hunting.

In terms of majors and SALC usage, the SALC is considered largely an English-language environment, which may attract those studying the English language more so than other majors. Languages other than English have their own spaces on campus, and so students in those departments might prefer to study in those spaces more frequently, thus accounting for the lower numbers of non-English majors.

Data collection

Data were collected through random sampling methods that had the 19 research team members conducting 109 structured interviews with students who were present on SALC premises. Of the 109 interviews conducted, two had to be removed as they were outside the determined participant parameters (N=107). The interview questions were displayed on a Google Form in English, and the interviewers, who were trained to ensure a high degree of consistency, entered responses from the interviewees verbatim (for further information see Asta & Mynard, 2018). Participants were asked to respond to the questions in English for ease of transcription and later analysis. Several categories of questions were asked, including but not limited to: participant background, language goals, English use and future directions for the SALC.

Data analysis

Responses from the interviews were downloaded as an Excel file and split into the following nine themes: (1) Favorite thing about the SALC, (2) Reasons for coming to the SALC, (3) Reasons for studying English, (4) Personal language goal, (5) Resources, (6) Who students enjoy speaking with and why, (7) Challenges, (8) Suggestions for SALC improvement, and (9) Visions for an ideal SALC and changes they would make to match those visions. Members of the research team then worked individually to generate descriptive codes to the responses within their assigned themes. These codes were discussed and code descriptors were developed before a second round of coding took place to ensure inter-coder reliability. The final round of coding saw several themes emerge.

Results and Discussion

Autonomy-Supportive Environment

The survey results suggest that students have a strong desire to communicate. When asked their reasons for visiting the SALC, 42% of responses cited communication purposes, which included talking to peers, teachers, learning advisors, and practicing English. Another 19% of responses cited independent study as their reason for visiting the SALC. Students use the SALC to watch movies, meet with learning advisors, complete language learning modules, or self-study. It can thus be inferred that students relate a significant portion of their communication to individuals, such as learning advisors and teachers. This in turn relates to the autonomy-supportive concept of structure, as the SALC provides structured practice for students with these individuals. This includes scheduled conversation and writing appointments with teachers in the Academic Support Area and casual conversation with teachers and students on the Yellow Sofas on the second floor. Additionally, the SALC provides spaces, such as the second floor study areas or first floor study rooms that allow students to engage in actions that reflect their current needs and motivations. In these ways, it can be argued that the SALC is successfully providing an autonomy-supportive environment.

When students were asked about their personal language goals, 45% of responses included communication with others. This includes communicating fluently with students and teachers, and making friends in English. Through this communication, students are able to form bonds with others, which can in turn be linked to relatedness. An additional 44% of responses were coded in the category of competence (e.g., workplace English, test scores, and skill development), while only 10% of responses were coded in the category of autonomy (e.g., to broaden horizons, pursue interests in English, or consume culture). From this data, it appears that relatedness and competence are key factors for students. Students want to communicate, but they also feel they need to improve their perceptions of their competence in order achieve fluid communication with others. The SALC aims to meet students’ needs by providing resources (such as teachers or learning advisors) and opportunities (such as learning communities and monthly workshops) for students to improve their competence.

When asked about changes that could be made to the SALC, 36% of responses mentioned more events and opportunities to use English. As mentioned above, students desire to communicate, but feel that they need to be more competent in order to do so. Although the SALC already provides learner events, learning communities, and workshops, the results show that students want more opportunities but may need more scaffolding to access those opportunities. (For a more detailed discussion, see “scaffolding needs” below.) Additionally, a further 28% of responses mentioned that students want changes in the environment of the SALC, such as a stricter language policy or more spaces (e.g., more Yellow Sofas or a larger Academic Support Area). As discussed above, students have not widely adopted the English-only policy on the second floor (Imamura, 2018).

From the data shown, it can be seen that students want to communicate, but that they feel they need more support in order to do so. They need scaffolding, either through more visible opportunities or through more structured practice. We also see that the SALC can be considered an autonomy-supportive environment, as it is already providing spaces, resources, and opportunities that our learners need.

Inconsistencies regarding communication

The interview results suggest that learners’ need for relatedness is highly important to them, particularly in the form of the desire to communicate with others and, in doing so, establishing pleasurable or emotional relationships. In describing their favorite thing about the SALC, they included communicating or people (e.g., learning advisors or teachers) in 47% of responses. Communication also represented the most common reason given for using the SALC, accounting for 42% of the responses. The act of communicating with others fulfills the SDT-related needs of students in various ways. One theme analyzed here addressed who students most enjoy speaking to in the SALC as well as their reasons why. The largest amount of answers given corresponded to relatedness, which represented 38% of the responses. Competence (22%) and autonomy (20%), however, were also prominently represented. The category of relatedness was defined by such factors as students’ enjoyment of the specific act of speaking with others, or qualities that made their communication partners appealing or created a bond (e.g., the partners’ kindness or personal attraction and interest). In responses coded under the category of competence, factors mentioned by students included the desire to improve their speaking or the ability to evaluate their own progress (e.g., “I realize that I can speak English”). Autonomy covered responses in which learners related asserting their own autonomy in service of things such as their own general enjoyment, cultural exchange, or to aid their motivation.

These issues were mirrored in students’ vision of the “perfect SALC” (Theme 9). Again, students expressed a need for communicating with people, which was addressed in 34% of the responses, encompassing aspects such as SALC areas that facilitate English use (such as the SALC’s English lounge), and events or opportunities for using language and interacting with people. Another 20% corresponded to students’ need for autonomy. In these responses, students described visions including more English being spoken of users’ own volitions or without hesitation.

Students were also asked what changes they wanted from the SALC. The results reveal that students desire scaffolding for their engagement within the communicative environment. When asked what improvements the SALC could make in order to help them use English more (Theme 8), 36% of the responses related a desire for more events and opportunities to use English, and an additional 28% were concerned with the SALC environment. Many responses in this latter category (18%) included a desire for a stricter language policy or English to be enforced. Similar trends were apparent when students described changes they would make to match their vision of a perfect SALC, particularly in the need for relatedness (e.g., the desire for expanded facilities for English use, events for language use, or opportunities for interaction).

Interestingly, a marked disparity exists between some of the results relating to how the SALC could better match the learners’ visions (Theme 9). Rather than suggesting any change made by the SALC, a considerable number of learners (21% of responses) commented in terms of their own autonomy, in that the change should come from the students themselves and that students were already capable of enacting such change. For instance, they expressed beliefs that students needed to be more active (e.g., “First, we have to change. If we come to the second floor, I think we should speak English only;” “Just speaking English is not efficient, so I’ll play some games with them.”) or that they needed to change something about themselves: “My personality would be…more active. When I go to the SALC, I get passive posture…and I want [to be] more active…”

In contrast, some learners desired more explicit pressure to use English. As previously described, in Theme 8, nearly 18% of the responses included a desire for more enforcement of English use. Furthermore, of the changes that learners would make for a more perfect SALC, 14% mentioned some form of external control or mediation. These changes included stricter enforcement of the language policy (e.g., “Making punishment for the people who can’t follow the English policy”) or more proactive behavior by teachers. These results mirror those of other studies, in which a majority of students surveyed were in favor of some form of English-only policy, with over 25% in favor of a strict policy (Imamura, 2017; Wongsarnpigoon & Hori, 2017). These trends conflict with the actual language policy decided upon by the SALC team, which establishes a non-directive stance (KUIS 8 Language Policy, 2018). This policy includes the use of signage, encouragement, and reminders but falls short of enforcement in the form of frequent reminders or asking violators of the policy to leave. The discrepancy between the desires of some learners and the SALC team suggests a need for further investigation into what scaffolding can be provided to help students follow the policy of their own volition.

Another disparity exists between the responses here and learners’ actual behavior in regards to events or opportunities for speaking to others. In this research, many students expressed the need for such events and chances to interact or meet with students. The SALC currently regularly provides a number of learner events, learner communities, and workshops each month. In an annual online survey regarding SALC usage (SALC student survey, 2018), between 75% and 90% of students replied that they had never taken part in a SALC event or workshop. When asked to provide reasons for not joining such events, over 37% stated that they were not aware of them, about 14% were not interested, and over 10% answered that they were nervous about joining. Some gap exists, therefore, between what students desire in terms of scaffolding and what they actually do. While students tend to say that they want more events or opportunities, it remains unclear whether they seek out such events and, when they are aware, why they do not participate. Again, additional research into interventions that could help the SALC better support students’ needs in this area would be beneficial.

Scaffolding needs

Survey data indicates that 60% of students face challenges related to language competence and communication. Students list comprehension, self-expression, vocabulary, fluency, and pronunciation as key challenge areas. As mentioned above, data indicates that 36% of students desire more communicative opportunities in the SALC. Communicative opportunities listed include more teacher interaction, events, and opportunities for friendship. This is supported by the 26% of students who described their ideal SALC as including more opportunities for interaction and speaking through communication with teachers and exchange students. Initial observations indicate that students struggle with language competence and seek to communicate more in English while in the SALC. As mentioned above, the data indicates a gap between students’ desire for communication and scaffolding and what resources they actually utilize in the SALC. While further research must be done on why students do not utilize all available SALC resources, it can be inferred that their perceived lack of language competence may be contributing to their limited use of current SALC resources. Two preliminary interventions, based on supporting data, are proposed below while other interventions and action-research projects will be discussed at a later date. Both interventions are aimed at further supporting learners’ understanding of autonomous behaviors and further encouraging students to utilize current autonomy-supportive aspects of the SALC.

The first proposed action research intervention involves two workshop series. The first workshop series focuses on developing students’ language competence and speaking confidence. This workshop will be led by an instructor, SALC learning advisor, or student. The intended outcome of this intervention is to give students the language tools, scaffolding, and encouragement needed to fulfill their desire to communicate more in the SALC through existing autonomy-supporting SALC resources (e.g., the Yellow Sofas, Academic Support Center, SALC hosted events, Language Partner Program, etc.). The second workshop series focuses on assisting students in their plans for speaking in the SALC. This workshop will also be led by an instructor, learning advisor, or student. Through scaffolded learning, students will develop a plan to communicate more in English in the SALC despite their perceived speaking abilities. To maximize student reach and attendance, these workshops are intended to be held every day for one week. Intervention success will be measured by pre- and post-workshop questionnaires, in addition to a follow-up questionnaire administered one week (or more) from the date of the workshop. This survey will ask students to indicate their current level of speaking confidence, its relation to the workshop, and the speaking or non-speaking related SALC resources they have utilized since the workshop.

The second proposed action research intervention will take place in the classroom. This intervention is centered around goal-setting and will be introduced to students by an instructor or learning advisor. In the initial goal-setting class, through instructor scaffolding, students will decide upon a language learning goal for the semester and will map out specific and measurable steps they plan to take to reach their goal. Students whose goal is to communicate more in English will be encouraged to include steps that build on existing language skills. These steps will include at home self-study as well as instructor suggested communicative-based SALC resources. It is our hope that instructor scaffolding will increase students’ use of SALC resources. In addition, as mentioned above, supporting data led us to infer that students’ lack of speaking competence may be contributing to their limited use of SALC resources. Data suggests that students will increase their use of SALC resources as they improve as they build on their language skills. To further scaffold student autonomy and measure the effectiveness of the intervention, students will be required to answer a series of goal reflection questions at the end of each week. Pre- and post-questionnaires will also be administered before and after the intervention.

The interventions mentioned above are intended to assist students in building speaking confidence and to help students achieve their goal of communicating more in English in the SALC. The anticipated benefits of these interventions are an increase in student autonomy and use of existing autonomy-supportive aspects of the SALC. Further research is needed on why students are not utilizing already existing SALC resources.

Limitations

This paper represents a part of a much larger study and as such, only two areas are discussed here. Firstly, due to the English-language nature of the interview, linguistic difficulties may have resulted in limited expressions of individuals’ ideas and opinions in relation to the SALC environment. A solution to this concern may lie in conducting research into specific areas of the SALC utilizing English and Japanese in order to yield richer data from which we will be able to evaluate how autonomy-supportive our SALC is. Additionally, the contradictions that arose between the students’ desire to communicate and their lack of action could not be fully explored here. Future studies could utilize qualitative methods, such as case studies or focus groups, in order to provide greater insight into this issue.

Conclusion

Policies, practices, and spaces all appear to play a role in the development of an autonomy-supportive self-access learning center. While our SALC has taken actions to revise policies, and provide supportive spaces so that the language-learning environment is inclusive and non-threatening, students still appear to want and need further support. Self-access centers, like our own, need to continue to provide their learners with scaffolding and opportunities to develop their competence so that they may engage with other learners and speakers of English. It is through these measures that self-access centers can ensure that they are creating autonomy-supportive environments for their students.

Notes on the contributors

Amelia Yarwood is a learning advisor at Kanda University of International Studies. Her research interests include L2 identity and motivation, learning strategies and curriculum design.

Andria Lorentzen is an instructor in the English Language Institute at Kanda University of International Studies. Her research interests include CALL, learner autonomy, and learner motivation.

Alecia Wallingford is an instructor at the English Language Institute at Kanda University of International Studies. Her research interests include learner autonomy, learner motivation, learner identity, critical thinking, and intercultural interaction.

Isra Wongsarnpigoon is a learning advisor at Kanda University of International Studies. He holds an M.S.Ed. from Temple University, Japan Campus. His research interests include learner autonomy, language learner motivation, and L2 vocabulary learning.

References

Asta, E., & Mynard, J. (2018). Exploring basic psychological needs in a language learning center. Part 1: Conducting student interviews. Relay Journal, 1(2), 382-404.

Curry, N., Mynard, J., Noguchi, J., & Watkins, S. (2017). Evaluating a self-directed language learning course in a Japanese university. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 14(1), 37-57.

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (2000). The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behaviour. Psychological Inquiry. 11, 227-268.

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (2016). Optimizing students’ motivation in the ear of testing and pressure: A self-determination theory perspective. In J. Wang, C. Liu and R. Ryan (Eds.), Building autonomous learners: Research and practical perspectives using self-determination theory. Singapore: Springer, 9-29.

Gillies, H. (2010). Listening to the learner: A qualitative investigation of motivation for embracing or avoiding the use of self-access centres. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(3), 189-211.

Grolnick, W., & Ryan, R. (1987). Autonomy in children’s learning: An experimental and individual differences investigation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 890– 898.

Hammond, J., Gibbons, P. (2002). What is scaffolding? In J. Hammond (Ed.), Scaffolding teaching and learning in language and literacy education. Newtown: PETA, 1-14.

Hobbs, M., & Dofs, K. (2017). Self-Access Centre and Autonomous Learning Management: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Going? Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 88-101.

Imamura, Y. (2018). Adopting and adapting to new language policies in a self-access centre in Japan. Relay Journal, 1(1), 197-208.

KUIS 8 Language Policy [internal document] (2018). Self-Access Learning Center, Kanda University of International Studies, Chiba, Japan.

Mynard, J., & Stevenson, R. (2017). Promoting learner autonomy and self-directed learning: The evolution of a SALC curriculum. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 169-182.

Ryan, R., Deci, E., & Grolnick, W. (1995). Autonomy, relatedness and the self; their relation to development and psychopathology. In D. Chicchetti and D. Cohen (Eds.), Manual of developmental psychopathology. New York: Wiley, 618–55.

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2008). Self-determination theory and the role of basic psychological needs in personality and the organization of behavior. In O. John, R. Robbins, & L. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research. New York: The Guilford Press, 654-678.

SALC Student Survey (2018). Unpublished raw data.

SALC Mission Statement (2017). Self-Access Learning Center, Kanda University of International Studies, Chiba, Japan.

Sierens, E., Vansteenkiste, M., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., Dochy, F. (2009). The synergistic relationship of perceived autonomy support and structure in the prediction of self-regulated learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(1), 57-68.

Sturtridge, G. (1997). Teaching and language learning in self-access centres: changing roles? In P. Benson and P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning. UK: Pearson Education Limited, 66-78.

Wongsarnpigoon, I., & Hori, M. (2017, December). Gathering input on a SALC: Design, administration and interpretation of a student survey. Poster session presented at the 2017 JASAL Annual Conference, Chiba, Japan.

Dear Andria, Alecia, Amelia, and Isra,

Thank you for sharing your exciting study! The scale of this study is really inspiring (109 interviews – wow!) and your data seems to have so much potential to contribute to this field. Also, I find your idea of approaching the data by using self-determination theoretical framework is unique and an effective way to evaluate a self-access center because its purpose is to promote learner autonomy.

In order to benefit more readers in wider institutions and organizations from your study, I feel that clarifying how this study will fill the gap in this field of research may be important. Also, your argument will be clearer and convincing if you could add more information (what is Yellow Sofas? How does “SALC provide spaces that allow students to engage in actions that reflect their current needs and motivations” happen?), and comparing and contrasting similar research in the discussion part. It will be great if we could see your summary of coded data in appendix too.

It was interesting to read about the gap of students’ desire for communication and what they actually do in the SALC. I think this kind of dilemma is common in language learning (e.g., students using their L1 in their English class even though they want to have more opportunities to use English). I believe you are collaborating with Ottawa University on linguistic risk-taking initiative project and that may provide you with some ideas for scaffolding the process. I look forward to reading your further study. Good luck!

Dear Satoko,

On behalf of the other authors, I would like to start with a thank you for your kind and useful comments. The Self-determination framework is indeed an exciting framework to use as I feel it opens up so many possibilities for evaluating the autonomy-supportive nature of not only classrooms but centres such as ours.

As for the risk-taking initiative project, it may very well be a good place to look for scaffolding the students’ communication skills. After all, identifying the things we are afraid of and taking action is one method of empowering ourselves! I am keen to look more closely at this project to see how it can be adapted to our self-access context. In particular, it would be interesting to investigate the students’ perceptions of risk-taking. Do they view it as necessary for their language learning to progress to the next level? How do students react when their risk-taking ends in failure? At what point do students perceive the risks to be too substantial to continue engaging in risk-taking behaviours?

Finally, thank you for your suggestions. The other authors and I shall work hard to improve our article based on your comments. All the best!