Son Van Nguyen, Doctoral School of Education, University of Szeged, Hungary

Anita Habók, Institute of Education, University of Szeged, Hungary

Nguyen, S. V. & Habók, A. (2020). Non-English-major students’ perceptions of learner autonomy and factors influencing learner autonomy in Vietnam. Relay Journal, 3(1), 122-139. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/030110

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

The present paper reports on some stages of an ongoing research project which investigates how Vietnamese non-English-major university students perceive learner autonomy (LA) and which factors, from their perspective, influence the promotion of LA. Data was collected using questionnaires administered to more than 1,500 university undergraduates from different higher education institutions in Hanoi, Vietnam, and 13 students participated in semi-structured interviews. The initial stage of the project, detailed here, was to validate the questionnaire on the basis of reliability and Messick’s (1995) framework of validity. The results revealed that reliability and most aspects of validity investigated in this research were adequately fulfilled, except for the relative goodness indices, which needed improvement. Currently, both quantitative data and qualitative data are being analyzed to reach conclusions. The research results are expected to help the research team to provide suggestions on how to foster LA in English tertiary education. Accordingly, those results will be of interest to language educators in Vietnam in particular, scholars who are researching LA, and those who are interested in the promotion of LA.

Keywords: perception; learner autonomy; Vietnam

Problem Statement

The 21st century has witnessed the globalization of English language, which is regarded as the tool for effective communication and mutual understanding among citizens of countries all over the world. Accordingly, learning English in order to become globalized is of great importance. There are a variety of ways to learn English that learners can employ. They can be formal schooling with teachers and peers, or education with the support of the Internet, and so forth. However, it is no one else but the learners who play the most vital role in any processes of language learning because these processes are largely dependent on the amount of effort given by the learners (Campbell & Snow, 2017).

Learner autonomy (LA) has been a reply to the 21st-century education’s challenges in connection with theories, learning styles and strategies, and approaches which can fulfill the demands of the labor market (Blidi, 2017). It has been hotly discussed in English language teaching (ELT) and learning for about four decades, and it is thought to yield positive achievements in teaching and learning a language like English (L. T. C. Nguyen, 2009). The globalization in economy entails the fact that education needs to produce those who are able to adapt their own training to meet all the requirements of the economy (Benson, 2000), and specifically in language teaching, supporting students to be autonomous learners is increasingly becoming one of the most important themes (Benson, 2013) and “one of the issues that needs to be addressed when the focus is on the learner in present day ELT” (Illés, 2012, p. 506). As a result, LA is considered “a precondition for effective learning” (Benson, 2013, p. 1), meaning that if a learner manages to foster his or her autonomy, not only will he or she learn languages better, but that person will also think more critically and take more responsibilities in the communities he or she gets involved in (Benson, 2013).

Although LA has its roots in Europe, it can be a reference which is especially relevant to learners in the contexts of developing nations (Smith, Kuchah, & Lamb, 2018). Vietnam, in our opinion, is no exception. The Vietnamese government is making efforts to promote English-language education (Trines, 2017), and it has been suggested that English be recognized as the second official language of Vietnam (VnExpress, 2018). In point of fact, regarding the tertiary level of the Vietnamese education system, the majority of universities have recently employed credit systems whose purpose is to promote self-learning more. This means that students have more time for learning and teaching by themselves outside classrooms, and they can earn credits for that self-learning. Thus, the amount of time in class and the number of courses such as English ones are reduced, and the students need to learn autonomously in order to gain knowledge and get positive learning achievements. Moreover, in accordance with Vietnam’s National Foreign Language 2020 Project launched by the Ministry of Education and Training (2008), by 2020, most Vietnamese graduates from higher education institutions are expected to have the capability to use languages independently and confidently in communications; studying; and working in the integrative, multilingual and multicultural context of the world. The National Foreign Language 2020 Project aims at turning the acquisition of foreign languages into strengths of Vietnamese people for national industrialization and modernization. The governmental efforts and the reforms aforementioned entail the fact that the teacher-centeredness prevalent in traditional teaching methods needs to be changed into student-centeredness, which allows students to be responsible for learning and participate in the learning process actively (Lak & Soleimani, 2017; L. Tran, N. Tran, Nguyen, & Ngo, 2019). Notably, the student-centeredness is intended to enhance LA (Dam, 1995), and it is appropriate for those who have more LA (Lak & Soleimani, 2017). The necessity for students’ LA, hence, is becoming higher and higher. According to Bui (2018), applying LA is “a prudent policy to high-quality education and English language teaching and learning” (p. 158), and LA “has been endorsed to be included in English language education from the policy level” (p. 161). However, as Vietnamese culture is deeply influenced by Confucian heritage (Bui, 2018; Dang, 2012; Humphreys & Wyatt, 2014; T. T. Tran, 2013), it can be easily seen that Vietnamese students obey instructions from teachers and express shyness and unwillingness in response to teachers’ questions (Bui, 2018; T. T. Tran, 2013). They are passive in learning, have neither the deep learning nor ability to understand issues in depth (Director, Doughty, Gray, Hopcroft, & Silvera, 2006), and self-teach or self-study poorly at home or in libraries (Vietnamnet, 2014). Besides, according to Trinh and Mai (2018), the students, especially non-English majors, show their reluctance to ask questions or express ideas, and they are unfamiliar with engaging activities. Thus, those students are criticized for lacking the facilitative skills and strategies to learn English effectively (Trinh & Mai, 2018). Many scholars indicate the alarming issues the labor market faces nowadays, such as students’ lack of fundamental knowledge as well as skills and students’ difficulties in the decision-making process (N. T. Nguyen, 2014). These issues will lead to low quality in the labor force.

We therefore wonder whether non-English-major students, who make up the majority of undergraduates in Vietnam, are aware of or possess any perceptions of LA and whether there are potential factors that impact on their autonomous learning. More importantly, LA has been hotly discussed among the scholars in the extensive literature. In Vietnam, however, it is seemingly a new and strange concept, and accordingly, the number of studies on this topic is still limited. Previous research has been done about teachers’ and English-major students’ beliefs about LA and their performances (Bui, 2016; Dang, 2012; Le, 2013; L. T. C. Nguyen, 2009; N. T. Nguyen, 2014; V. T. Nguyen, 2011) and strategies to foster autonomous learning (Cao, 2018; Hoang & Nguyen, 2010; Humphreys & Wyatt, 2014; N. T. Nguyen, 2012; Phan, 2015; L. Q. Tran, 2005). The perceptions of LA from non-English-major students and the factors which influence LA in learning English have not been taken into great consideration. Therefore, this study was carried out to fill this gap. We decided to conduct a study on non-English-major students’ perceptions of LA and on the factors influencing LA in the context of Vietnam.

Theoretical Background

There is growing evidence that through the last few decades, the concept of LA in the fields of applied linguistics and language learning has been diffused and adapted all over the world depending on the perspectives underlying them. We will theorize and discuss the idea of LA from the Vietnamese perspective. Vietnam is a country in Southeast Asia which has many points in common with some other nations in East Asia such as China, Japan, or Korea. In the past, it was dominated by Chinese emperors for approximately 1,000 years, and Confucianism was selected as the national religion in several dynasties. Its ideology, therefore, is deep-seated in the Vietnamese culture (Bui, 2018; Le, 2013). In addressing education, Confucianism postulates that people have to invariably learn, and only by learning do they arrive at an understanding of life, which emphasizes studying or knowledge—Trí— one of five virtues (ngũ thường) (Truong, 2013). As a result, one of the important traditional values in Vietnamese education is a liking for learning, and respect for learning becomes the abiding characteristic (Pham & Fry, 2004). Generally, Vietnamese people highly appreciate academic achievement and believe that it comes from hard work (Le, 2013). As the Vietnamese saying goes, “có công mài sắt, có ngày nên kim” (literally, if a person is hard working and persistent enough, he can make a needle out of a metal bar). This saying can be understood as “practice makes perfect.” There are several other equivalent proverbs, including “siêng làm thì có, siêng học thì hay,” which means “the more you work, the more you have; the more hardworking you are, the more knowledgeable you become,” or “cần cù bù thông minh,” which means “hard work compensates for lack of intelligence.”

The values of diligence and academic achievement can be associated with the construct of LA, although it is believed to come from Western countries (Murase, 2012; Pokhrel, 2016; Surma, 2004). According to Usuki (2007), the literature predicates that LA requires students to actively participate in decision-making and knowledge-constructing. Furthermore, learners need to interact with the community or to work as hard as possible in real-world situations with materials such as newspapers and magazines. These attributes enable learners to be successful in language learning with their own hard work. We strongly believe that responsibility is a precursor of hard work and success. We are of the opinion that LA in language learning refers to taking responsibility of learning the language, or English in this case. By claiming this point, we share the same viewpoint with Oxford (2008) and Le (2013). Accordingly, responsibility entails students’ conscious awareness of their main role in language learning. The awareness is necessary for students to make continual progress towards language competence enhancement (Emerson, 2014). Such an awareness, or what is labeled by Emerson (2014) as “mindful” (p. 148), is linked to the meaning of an active learner construed by Asian culture vis-à-vis Western culture. That is to say, learners should make hidden mental efforts rather than overt mental behavioral attempts (Le, 2013; Usuki, 2007). Hence, the ultimate goal of LA could be “from the viewpoint of internal mental involvement with the content rather than the point-of-view of students learning on their own” (Usuki, 2007, p. 2). Notably, the sociocultural, political, and institutional milieus surrounding learners contribute to the development of LA, but their personal conscious awareness is of paramount importance. This underscores what Hsu (2005) portrays as willpower and what Le (2013) interprets as personal determination.

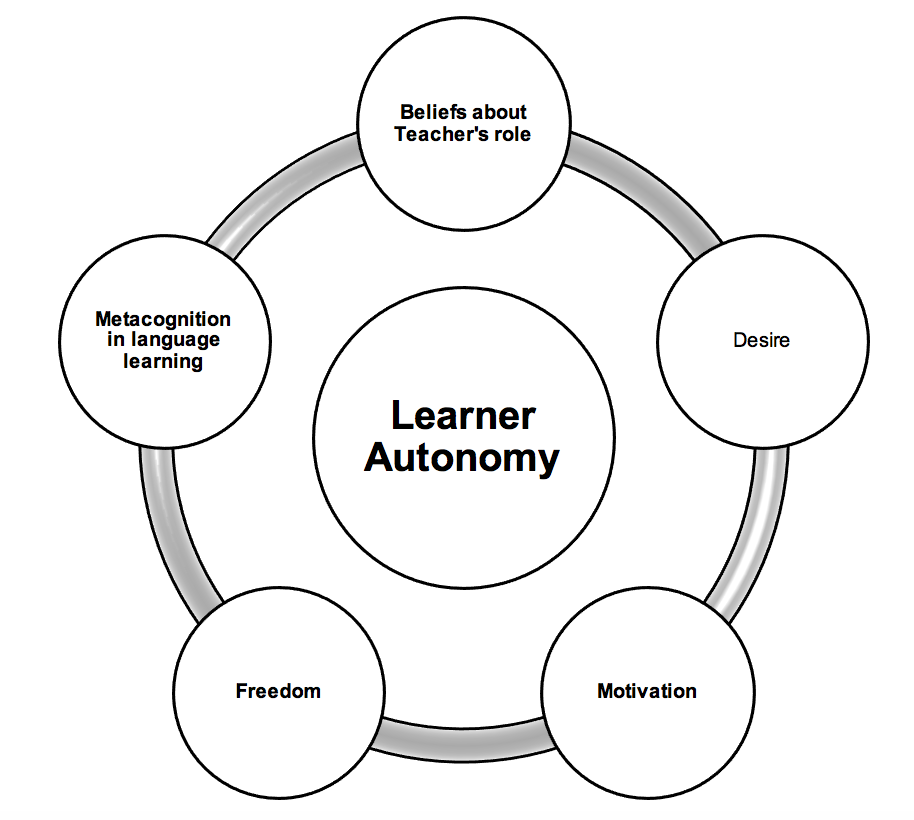

To conceptualize LA, the theoretical background of this research adapted the Bergen definition, in which, as described by Dam (1995), LA “is characterized by a readiness to take charge of one’s own learning in the service of one’s needs and purposes. This entails a capacity and willingness to act independently and in cooperation with others, as a socially responsible person” (p. 1). Accordingly, LA requires both the willingness and capacity to take on the responsibility for learning. According to S. V. Nguyen and Habók’s (2019) argumentation, those two components are important to learn foreign languages effectively and satisfy language needs in the day-by-day changing world of the industrial revolution 4.0. Willingness includes motivation and beliefs about the teacher’s role. Capacity consists of ability, which refers to metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive skills, desire, and freedom. We would like to combine metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive skills into metacognition in language learning as one component of LA. This point is aligned with Dixon’s (2011) conceptualization of LA, which includes metacognition as a necessary component for LA. Therefore, the construct of LA is comprised of four components, which are beliefs about teacher’s role, motivation and desire, metacognition, and freedom, which formed a basis for establishing and developing the instruments in this study. The conceptualization of LA in this research project can be found in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. The conceptualization of LA in this study (S. V. Nguyen & Habók, 2019)

Aims and Objectives

There are three main aims to be achieved.

Firstly, the study is aimed at investigating how students who major in subjects other than English perceive LA. The literature was reviewed systematically so that an operational definition of LA could be provided and a framework from different perspectives for a questionnaire survey could be established. The survey, then, was tested and delivered in order to generate the dimensions of LA in students’ perceptions. The data for this aim was also gained by semi-structured interviews.

Secondly, the research examined the factors around the learners which could potentially influence their autonomous learning, including internal factors and external factors. The former refers to the factors coming from the learners themselves, whereas the latter emphasizes the factors from the learning environment such as teachers, peers, and curricula. They may be either positive or negative. The data was collected through both surveys and interviews in order that the points could be categorized to reach reasonable conclusions.

Lastly, induced from their perceptions and the factors above, suggestions are given to enhance LA for students. These suggestions will be hopefully given in the forms of discussions, training workshops, seminars, and other extracurricular activities which may involve both students and teachers. The activities might be undertaken at the beginning of the semester or the school year.

In brief, the aims and objectives could be summarized into three main research questions as follows:

- What are the non-English-major students’ perceptions of learner autonomy?

- What are the factors that influence students’ learner autonomy?

- What can be suggested to foster learner autonomy among students?

Significance

The research is hoped to offer more insights into how LA is perceived by non-English-major students and which factors have an impact on their autonomous learning in the specific context of Vietnam. As a result, suggestions and implications are provided to foster LA—one of the essential qualities in learning and living. These will help to enhance the quality of language teaching for teachers and language learning for non-English-major students, who account for the majority of students and the so-called labor force in Vietnam in the future. Hence, hopefully, this investigation will contribute to the improvement in quality of higher education in Vietnam in its process of globalization and internationalization.

Methodology

Mixed-methods design

The study employs both quantitative and qualitative data. A mixed-methods design was adopted because it helps the researcher to enhance the study’s quality (Johnson & Christensen, 2012). It provides more insights into the problems, facilitates an expanded understanding of those problems (Creswell, 2014), and addresses many aspects of research questions in academic studies when used (Dahlberg & McCaig, 2010).

Data collection instruments

Two types of data have been collected: quantitative from survey questionnaires and qualitative from semi-structured interviews. The critical review of literature formed the basis of the questionnaire’s scales and the interview’s questions.

The first instrument was meant to elucidate the questions related to students’ perceptions of LA and the factors which have an impact on their LA. The data was collected from the questionnaire using Likert-scale items, which provide “a quantitative or numeric description of trends, attitudes, or opinions of a population” (Creswell, 2014, p. 155). We carefully reviewed the literature and looked for well-established LA questionnaires. We borrowed and adapted items from previously validated questionnaires that were psychometrically sound. After the systematic literature review, we had a pool of 87 items. The questionnaire comprised 37 items adapted from Hsu (2005), 19 items from Dang (2012) which were previously adapted from Yang (2007), 18 from Chan, Spratt, and Humphreys (2002), eight from Le (2013), seven from Cotterall (1999), seven from Swatevacharkul (2009), three from Ming and Alias (2007), two from Dixon (2011), and two from Cotterall (1995). We ourselves created four items. Eight items were used by both Chan et al. and Le; seven items were shared by Hsu and Swatevacharkul; and five items were utilized by both Cotterall and Hsu. The questionnaire was designed with a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). We arranged the items randomly to enhance objectivity.

The second instrument used to answer the research questions using qualitative data was a series of semi-structured interviews. The interviews would “allow respondents to say what they think and to do so with greater richness and spontaneity” (Miller & Brewer, 2003, p. 167). Additionally, the interviews gave us the flexibility to change the sequence of questions as well as get more information about both LA perceived by students and any influencing factors (Miller & Brewer, 2003). We conducted the face-to-face individual semi-structured interviews. The questions were framed based on the previous studies and the scales of the questionnaires. During the interviews, many questions arose, subject to the conditions in each interview.

Participants

A total of 1,565 university students from seven higher-education institutions in Hanoi, Vietnam voluntarily participated in the research. They comprised 62% second-year students (n = 971), 23.7% third-year students (n = 371), 11.9% fourth-year students (n =186), and 2.4% fifth-year students (n = 37). Among the participants, 37.8% were female (n = 591), and 62.2% were male (n = 974). They have learned English in higher education for at least one semester, so they may have been more familiar with and may have gained better experience in the English-learning environment at the tertiary level than their first-year peers.

Data collection and analysis process

After the questionnaire development, we discussed it with our research team. Next, it was translated into Vietnamese in order that all the students could understand the content of the questionnaire. We translated the Vietnamese version back into English with the support of our colleagues who have expertise in ELT and are experienced instructors of English: one Vietnamese-American based in the US, one PhD candidate based in Australia, one PhD candidate based in New Zealand, one ELT expert who got her PhD from an Australian university, and three language teachers with master’s degrees working in Vietnam. We changed some word choices on the basis of comparison and contrast among the English versions. At last, a Vietnamese version of the questionnaire was successfully generated. We sent it to some other ELT professionals for comments on face and content validity. It was also sent to four Vietnamese students, who were not recruited in the study. They spent around 30 minutes reading and completing it. The piloting indicated that it was not difficult for them to understand the survey and that they thought that the survey had a user-friendly design. Hence, we made no changes to that Vietnamese version, and we officially employed it in this research (see Appendix for an extract from the questionnaire).

After getting ethical approval from the institutional review board at the University of Szeged and permission from the Vietnamese universities, one of us talked to the students in each class about the study’s aims, significance, methods, and ethical issues. We informed the students that their responses would not negatively influence their grades and would be kept confidential and used only for research purposes. The paper-and-pencil questionnaires were delivered to 1,600 students, and any questions related to the study were satisfactorily answered. In all, 1,565 questionnaires were returned, whereas 35 were eliminated due to being incomplete or to the participants’ decision not to have their responses included. This represented an approximately 98% response rate. Then, we elicited 13 students, who were randomly selected from different universities, for the interviews. The interviews in Vietnamese were recorded with the students’ permission. One of us, a native Vietnamese speaker, conducted the interviews. Each interview lasted about 30 minutes.

After the administration of the questionnaire, the data was entered into SPSS version 24, SPSS AMOS, and SmartPLS 3 and analyzed in order to recognize missing values and assess the validity and reliability of the questionnaire. The data was calculated and then categorized in order to make generalizations and reach conclusions about the population (Creswell, 2014). We completed the validation of the questionnaire. The framework of validity proposed by Messick (1995) was employed in order to evaluate validity. It includes six aspects, which are content, substantive, structural, generalizability, external, and consequential, but this study only elaborated on five of them (excluding generalizability). The relliability was assessed on the basis of Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and rho_A reliability.

As for the interviews, the recordings were then coded with the coding systems and transcribed. The transcriptions were double-checked to make sure that no information was missing before they were carefully translated. The data was translated from Vietnamese to English; afterwards, the translated version was reviewed by ELT experts. Next, with the help of ATLAS.ti software, it was classified into different themes to enable us to answer the research questions together with data from the questionnaire.

Preliminary Results

In this report, we present some validational findings of the questionnaire (for more details, see S. V. Nguyen & Habók, 2019).

In terms of validity, three aspects of validity, including content, substantive, and consequential validity, were adequately explained and properly fulfilled. The external validity was assessed using convergent and discriminant evidence. The former was based on factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and CR, whereas the latter employed three different criteria including the Fornell–Larcker criterion, the cross-loadings, and the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT ratio). According to the statistical analysis, all the values of factor loadings, AVE, CR, and the three criteria above were satisfactory, which meant that external validity was established. The structural aspect of validity was shown by exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The former allowed us to exclude the items based on loadings, extraction, rotation, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity and to come up with a proposed model. There were 40 out of 87 items left. Afterwards, CFA enabled us to investigate that 40-item five-factor model, and we used a set of goodness-of-fit indices including four absolute fit indices, which are Chi-square, SRMR, RMSEA, and RMS_theta, as well as three incremental indices, which are TLI, NFI, and CFI. The data analysis indicated an adequate level of all the absolute goodness-of-fit indices and a level of goodness of incremental indices which was slightly lower than the standard.

Regarding reliability, we worked out three distinguishable values, including Cronbach’s alpha, CR, and rho_A. The whole questionnaire of 40 items and the scales revealed high or acceptable level of reliability.

It is highly recommended that there should be more and more validational processes in different samples so that the literature can be enriched.

Progress and Further Steps

After the validation process, currently, we are making efforts to work on the statistical data and the thematic data. We are using SPSS version 24 to obtain both the descriptive statistics and the inferential statistics from the scales. We are employing ATLAS.ti software to manage the interview data after transcribing the recordings and translating the transcripts. At the same time, we are combining two types of data to reach proper conclusions. We hope to publish our further findings in journals and edited books as well as present our research at international conferences.

In the near future, we will collect more qualitative data from the same pool of students because we see that the interview data that we have collected so far provides us with valuable insights into their perceptions of the issues related to LA which sometimes surprised us. Besides, we will consult experts in statistics in order to develop the quantitative part of our analysis for more inferential statistics.

Notes on the contributors

Son Van Nguyen is a PhD student at Doctoral School of Education, University of Szeged, Hungary. He has had experience as an instructor of foreign language at some higher-education institutions in Vietnam. His research areas include learner autonomy, motivation, learner’s beliefs, TESOL methodology, and language teaching in higher education.

Anita Habók (PhD) works as an assistant professor at Institute of Education, University of Szeged, Hungary. She mainly studies language learning strategy use, self-regulated learning, and learning to learn. She has published her work in Frontiers in Psychology, Cogent Education, Early Childhood Education Journal, LIBRI, SpringerPlus, and so on.

Acknowledgement

Son Van Nguyen is being supported under Stipendium Hungaricum scholarship by Tempus Public Foundation, Hungary.

Anita Habók is supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

References

Benson, P. (2000). Autonomy as a learners’ and teachers’ right. In I. Mcgrath, B. Sinclair, & T. Lamb (Eds.), Learner autonomy, teacher autonomy: Future directions (pp. 111–117). Harlow, UK: Longman.

Benson, P. (2013). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning (2nd ed.). Abingdon, UK & New York, NY: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833767

Blidi, S. (2017). Collaborative learner autonomy. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2048-3_1

Bui, N. (2018). Learner autonomy in tertiary English classes in Vietnam. In J. Albright (Ed.), English tertiary education in Vietnam (pp. 158–171). Abingdon, UK & New York, NY: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315212098-12

Bui, N. T. (2016). Investigating university lecturers’ attitudes towards learner autonomy in the EFL context in Vietnam. (PhD thesis). University of Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia. Retrieved from https://nova.newcastle.edu.au/vital/access/manager/Repository/uon:28953

Campbell, M., & Snow, D. (2017). More than a native speaker: An introduction to teaching English abroad (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: TESOL International Association.

Cao, P. T. (2018). Using project work to foster learner autonomy at a pedagogical university, Vietnam: A case study. HNUE Journal of Science , 63(5A), 27–37.

Chan, V., Spratt, M., & Humphreys, G. (2002). Autonomous language learning: Hong Kong tertiary students’ attitudes and behaviours. Evaluation & Research in Education, 16(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500790208667003

Cotterall, S. (1995). Readiness for autonomy: Investigating learner beliefs. System, 23(2), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/0346-251X(95)00008-8

Cotterall, S. (1999). Key variables in language learning: What do learners believe about them? System, 27(4), 493–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(99)00047-0

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.

Dahlberg, L., & McCaig, C. (2010). Practical research and evaluation : A start-to-finish guide for practitioners. Singapore: SAGE Publications.

Dam, L. (1995). Learner autonomy 3: From theory to classroom practice. Dublin, Ireland: Authentik.

Dang, T. T. (2012). Learner autonomy perception and performance: A study on Vietnamese students in online and offline learning environments. (PhD thesis). La Trobe University, Budoora, Victoria, Australia. Retrieved from http://arrow.latrobe.edu.au:8080/vital/access/manager/Repository/latrobe:34050;jsessionid=47F349644B7E91EBE7C1676C9B3D39D0?exact=sm_type%3A%22Thesis%22&f1=sm_creator%3A%22Dang%2C+Tin.%22&f0=sm_subject%3A%22Students+–+Attitudes.%22

Director, S. W., Doughty, P., Gray, P. J., Hopcroft, J. E., & Silvera, I. F. (2006). Observations on undergraduate education in computer science, electrical engineering, and physics at select universities in Vietnam. Hanoi, Vietnam: Vietnam Education Foundation. Retrieved from https://home.vef.gov/download/Report_on_Undergrad_Educ_E.pdf

Dixon, D. (2011). Measuring language learner autonomy in tertiary-level learners of English. (Unpublished PhD thesis). University of Warwick, Coventy, UK. Retrieved from http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/58287/

Emerson, J. E. (2014). Mindful learners: Encouraging English language learners to be active, autonomous, and mindful. In E. Doman (Ed.), Insight into EFL teaching and issues in Asia (pp. 147–156). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Hoang, L. T., & Nguyen, H. T. (2010). How to foster learner autonomy in teaching Country Studies at Faculty of English, Hanoi National University of Education. Journal of Science, Vietnam National University, 26(4), 239–245. Retrieved from https://js.vnu.edu.vn/FS/article/view/2569

Hsu, W. C. (2005). Representations, constructs and practice of autonomy via a learner training programme in Taiwan. (Unpublished PhD thesis). University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK.

Humphreys, G., & Wyatt, M. (2014). Helping Vietnamese university learners to become more autonomous. ELT Journal, 68(1), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/cct056

Illés, E. (2012). Learner autonomy revisited. ELT Journal, 66(4), 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccs044

Johnson, B., & Christensen, L. (2012). Educational research: Quantitive, qualitative, and mixed approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Lak, M., & Soleimani, H. (2017). The effect of teacher-centeredness method vs. learner-centeredness method on reading comprehension among Iranian EFL learners. Journal of Advances in English Language Teaching, 5(1), 1–10. Retrieved from http://european-science.com/jaelt/article/view/4886

Le, Q. X. (2013). Fostering learner autonomy in language learning in tertiary education: An intervention study of university students in Hochiminh City, Vietnam. (PhD thesis). University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK. Retrieved from http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/13405/

Messick, S. (1995). Standards of validity and the validity of standards in performance assessment. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 14(4), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.1995.tb00881.x

Miller, R. L., & Brewer, J. D. (Eds.). (2003). The A–Z of social research. London, UK: SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857020024

Ming, T. S., & Alias, A. (2007). Investigating readiness for autonomy: A comparison of Malaysian ESL undergraduates of three public universities. Reflections on English Language Teaching, 6(1), 1–18. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.583.733&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Ministry of Education and Training. (2008). Quyet dinh ve viec phe duyet de an “Day va hoc ngoai ngu trong he thong giao duc quoc dan giai doan 2008–2020.” No. 1400/QD-TTg. [Decision No. 1400/QD-TTg on the approval of the project “Teaching and learning foreign language in the national education system in the period 2008–2020”]. Hanoi, Vietnam: Vietnam National Politics Publications.

Murase, F. (2012). Learner autonomy in Asia: How Asian teachers and students see themselves. In T. Muller, S. Herder, J. Adamson, & P. S. Brown (Eds.), Innovating EFL teaching in Asia (pp. 66–81). Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230347823_6

Nguyen, L. T. C. (2009). Learner autonomy and EFL learning at the tertiary level in Vietnam. (PhD thesis). Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand. Retrieved from http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/handle/10063/1203

Nguyen, N. T. (2012). “Let students take control!” Fostering learner autonomy in language learning: An experiment. International Conference on Education and Management Innovation, 30, 318–320. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/06f8/2df6b5f7d5c5098b1c8797ec308c8d122142.pdf

Nguyen, N. T. (2014). Learner autonomy in language learning: Teachers’ beliefs. (PhD thesis). Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia. Retrieved from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/69937/

Nguyen, S. V., & Habók, A. (2019). Constructing and validating the learner autonomy perception questionnaire. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Nguyen, V. T. (2011). Language learners’ and teachers’ perceptions relating to learner autonomy—Are they ready for autonomous language learning? VNU Journal of Science, Foreign Languages, 27(1), 41–52. Retrieved from https://js.vnu.edu.vn/FS/article/view/1463/1427

Oxford, R. L. (2008). Hero with a thousand faces: Learner autonomy, learning strategies and learning tactics in independent language learning. In S. Hurd & T. Lewis (Eds.), Language learning strategies in independent settings (pp. 41–63). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847690999-005

Pham, H. L., & Fry, G. W. (2004). Education and economic, political, and social change in Vietnam. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 3, 199–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-005-0678-0

Phan, T. T. (2015). Towards a potential model to enhance language learner autonomy in the Vietnamese higher education context. (PhD thesis). Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia. Retrieved from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/82470/

Pokhrel, S. (2016). Learner autonomy: A Western hegemony in English language teaching to enhance students’ learning for non-Western cultural context. Journal of NELTA, 21(1–2), 128–139. https://doi.org/10.3126/nelta.v21i1-2.20209

Smith, R., Kuchah, K., & Lamb, M. (2018). Learner autonomy in developing countries. In A. Chik, N. Aoki, & R. Smith (Eds.), Autonomy in language learning and teaching: New research agendas (pp. 7–27). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-52998-5_2

Surma, M. U. (2004). Autonomy in foreign language learning: An exploratory analysis of Japanese learners. (PhD thesis). Edith Cowan University, Perth, Australia. Retrieved from https://ro.ecu.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1786&context=theses

Swatevacharkul, R. (2009). An investigation on readiness for learner autonomy, approaches to learning of tertiary students and the roles of English language teachers in enhancing learner autonomy in higher education. [Research report, Dhurakij Pundit University, Thailand]. Retrieved from http://libdoc.dpu.ac.th/research/134463.pdf

Tran, L., Tran, N., Nguyen, M., & Ngo, M. (2019). ‘Let go of out-of-date values holding us back’: Foreign influences on teaching-learning, research and community engagement in Vietnamese universities. Cambridge Journal of Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2019.1693504

Tran, L. Q. (2005). Stimulating learner autonomy in English language education: A curriculum innovation study in a Vietnamese context. (PhD thesis). University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Retrieved from https://dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=d5d936f4-9637-4b13-989a-aea84a94f80e

Tran, T. T. (2013). The causes of passiveness in learning of Vietnamese students. VNU Journal of Education Research, 29(2), 72–84. Retrieved from https://js.vnu.edu.vn/ER/article/view/502

Trines, S. (2017, November 8). Education in Vietnam. World Education News + Reviews. Retrieved December 20, 2019, from https://wenr.wes.org/2017/11/education-in-vietnam

Trinh, H., & Mai, L. (2018). Current challenges in the teaching of tertiary English in Vietnam. In J. Albright (Ed.), English tertiary education in Vietnam (pp. 40–53). Abingdon, UK & New York, NY: Routledge.

Truong, T. D. (2013). Confucian values and school leadership in Vietnam. (PhD thesis). Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand. Retrieved from https://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10063/2774/thesis.pdf?sequence=2

Usuki, M. (2007). Autonomy in language learning: Japanese students’ exploratory analysis. Nagoya, Japan: Sankeisha.

Vietnamnet. (2014, December 16). 60% of university students cannot meet self-study requirements. Vietnamnet. Retrieved September 25, 2017, from http://english.vietnamnet.vn/fms/education/118915/60–of-university-students-cannot-meet-self-study-requirements.html

VnExpress. (2018, December 20). English as an official language in Vietnam: Would it work? Retrieved December 20, 2019, from https://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/english-as-an-official-language-in-vietnam-would-it-work-3852677.html

Yang, T. (2007). Construction of an inventory of learner autonomy. On CUE, 15(1), 2–9. Retrieved from https://jaltcue.org/files/OnCUE/OnCUE_15_1.pdf

I very much enjoyed reading this article. As I was previously based in Southeast Asia, including 3 years in Vietnam, it was interesting to read about research into Vietnamese non-English-major students’ attitudes about learner autonomy (LA). Below I would like to address what I believe to be the particular strengths of this paper; and I would also like to ask some questions related to the content and findings of the study.

The article begins by discussing global trends related to English and how Vietnam fits into this larger picture. Importantly, you mention that, to date, few studies have focused on Vietnamese non-English-major students’ attitudes toward LA. I agree that this is particularly important when we consider the role of English in the globalized economy as non-English-majors certainly account for the majority of Vietnamese learners of English. I also enjoyed your linking of LA with the historical context of Confucianism in Vietnam and East Asia. Interestingly, Murray (2014) also made a connection between LA and Confucianism, recognizing the importance of the social dimensions inherent in both. All in all, it was a pleasure to read a study that drew on the extensive literature on LA in language learning while at the same time localizing the discussion in terms of education in Vietnam.

I also appreciated the very detailed descriptions of the methodology. It was particularly interesting to read about which LA researchers’ survey instruments that yours drew upon. The article also included a thorough explanation of the statistical analyses that you have conducted to date.

In reading your paper, I did have some questions that I hope that you can respond to. As mentioned above, you indicate the sources of the questions in your survey. However, you only share a small number of survey questions in the appendix. I am curious to know more about the questions that were used in our final questionnaire. If it is not appropriate to share the entire survey, it would be interesting to at least know what the various sections of the instrument are so that the reader could see how it relates to the stated objectives of the study. Similarly, it would be valuable to know more about the contents of the semi-structured interviews. While you describe the interview methods in good detail, I would like to know more about the questions asked during these sessions. Finally, I was wondering if it would be possible to share some initial findings. While I appreciate that the study is not yet complete, I believe that readers of Relay Journal would be interested to learn of any interesting preliminary findings, or even some interesting anecdotal ones.

Once again, I thoroughly enjoyed reading this important paper regarding LA and Vietnamese non-English-major students. I very much look forward to reading more papers that are the result of this ambitious study.

Murray, G. (Ed.). (2014). Social dimensions of autonomy in language learning. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

On behalf of our research team, I would like to say sincere thanks to Mr. Andrew Tweed for your constructive feedback and your interesting questions.

I am so sorry that we did not provide and attach more sections of the questionnaire and of the interviews in the appendix. We will do that in the revised version and we hope that our revision will satisfy you. Thank you in advance for your patience and understanding.

Regarding some initial findings, we have just analyzed both quantitative and qualitative data for two scales named “beliefs about teacher’s role” and “motivation and desire to learn”. Generally, the students in our sample tended to be more teacher-centered although we saw some evidence of their sense of responsibility in learning. We found that those with higher marks were less likely to have teacher-centered beliefs than their counterparts with lower marks. In terms of motivation and desire to learn English, the students were highly motivated and they learned English mainly for their future studies and career, which was explained by the socio-cultural context. We did not find a difference in motivation among genders but we did see a difference in motivation between second-year students and third-year students and between students with high marks and those with low marks. Currently, we are working on the next scale of metacognition and the correlations between the scales.

Once again thank you for your sharing. If you have more concerns, please let me know. I do wish you safety and health during the pandemic.