Jason R. Walters, Nagoya University of Foreign Studies

Walters, J. R. (2021). Pursuing PERMA in a pandemic: Reflections on a socially-distanced advising session. Relay Journal, 4(1), 5-15. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/040102

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

Drawing on transcribed excerpts, this reflection describes an online advising session conducted by the author, a full-time EFL lecturer and developing language learning advisor, with a language learner attending a private Japanese university. This follows from a previous advising session conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and explores the impact of the pandemic on the learner’s reported motivation. The advisor engages with the advisee to identify obstacles to motivation and other essential elements of overall well-being and is required to adapt after recognizing that a prepared advising tool is poorly suited to the advisee’s needs. Together, the pair identifies an opportunity to create positive associations between language learning and the advisee’s gaming hobby. The author experiences a greater sense of authenticity in the advisor role after considering the needs of his advisee via his existing research interest in positive psychology.

Keywords: advising, advisor development, PERMA, positive psychology, reflective practice

Examining novice learning advisors’ early sessions provides insight into challenges they may initially face and unanticipated breakthroughs they experience while also illuminating concepts and strategies they may have internalized during their training. While working toward my certification as a language learning advisor, I had the pleasure of conducting several advising sessions with a high-achieving former student of mine named Nanako. Reflecting on our first session, conducted in January 2020, I recalled experiencing feelings of inauthenticity when introducing advanced advising strategies (e.g., using metaphor) or advising tools. As the recursive nature of learning advising ensures that early sessions lay the groundwork for advisors’ ongoing development, I aimed to investigate these feelings further by transcribing and reflecting on subsequent sessions.

Soon after our first session, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted my plan to conduct more frequent face-to-face advising sessions with Nanako. We met again several months later when Nanako agreed to participate in a follow-up session in July 2020 using the Zoom videoconferencing application and provided consent to be recorded with the understanding that transcripts may be shared with advisors, teachers, and researchers for the purposes of professional development or publication.

Over time, via transcribing, revisiting, and reflecting on early sessions, novice advisors are able to notice greater congruence between their own dispositions, anxieties, and areas of expertise and the theoretical models acquired in training, and to more fully appreciate how their own use of dialogue contributes to a session’s outcome (Mynard, 2018). In this reflection on our second advising session, I describe feeling greater legitimacy in the advisor role after examining my advisee’s affective state through a more familiar theoretical perspective. The lens of positive psychology reveals links between Nanako’s pandemic-related struggles with motivation and possible deficiencies in the elements of PERMA, an acronymic inventory of the conditions required for human flourishing: 1) positive emotion, 2) engagement, 3) relationships, 4) meaning, and 5) achievement (Seligman, 2010).

Session Context, Participants, and Aims

Nanako, a 19-year-old in her second year as a university English major, taught English to young learners at a local cram school and was active in international social groups on campus. Her learning history featured early exposure to English through family members interested in international travel, and her oral and written production of English was, in general, more advanced than that of her peers. Our previous discussion—my first attempt at authentic advising—had examined Nanako’s goal to study abroad. In that session, she was able to identify clear intermediate goals; among these, she viewed achieving a satisfactory TOEFL score to be the most difficult. By the session’s end, Nanako had begun to develop a new personalized study schedule and agreed to experiment with it before our next session.

Reflecting on feelings of inauthenticity I had experienced in our first session, I felt that my difficulties had sprung largely from the way I had framed the session in my mind. Though the initial session had been essential to my professional development, it was conducted as a course assignment for a learning advisor training program. Consequently, I had felt immense pressure to produce some result to report to instructors and peers: e.g., to notice a visible shift in perspective, create an “a-ha moment,” or find a powerful question to ask at a key moment. The problem here is perhaps obvious in hindsight—I spent inordinate time and energy in my own head, relegating my advisee to a supporting role in her own advising session.

Hoping to follow up on Nanako’s experiences with the study schedule and aware of the impact of the pandemic on young learners’ feelings of well-being and motivation (Fansury et al., 2020), I approached this second session with three objectives I felt would support my growth as an advisor:

- To use basic advising strategies (e.g., rephrasing, empathizing, repeating) authentically in an online environment

- To attend closely to the advisee’s affective state

- To introduce an advising tool for the first time

Remembering feelings of awkwardness introducing new strategies or tools in my advising training and first session, I felt that preparing a specific tool ahead of time might help me introduce it more organically and enable me to work past feelings of inauthenticity. The Goal-Setting Pyramid (Kato & Mynard, 2016) is one such tool; its tiered visual design places the advisee’s primary goal at the apex and allows them to visualize the foundation of daily habits, short-term objectives, and larger goals that will support them in achieving it. Feeling more at ease with this tool than others after having successfully piloted it in a classroom setting, I prepared a digital version for Nanako’s session.

Session Overview

Exploring the current situation

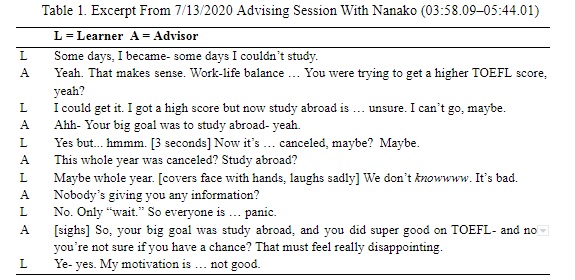

As several months had passed since our previous discussion, we began by simply catching up. She was eager to talk about about her new pet and spring holidays spent barbecuing with family. However, when the topic turned to language learning, she appeared hesitant to speak. I probed further; in the transcript contained in Table 1, Nanako reveals concerns beyond her study schedule.

Having spent the previous year working toward her primary goal of studying abroad only to have that incentive removed by forces outside of her control, Nanako reported experiencing tremendous frustration and confusion. This issue is common among my students, and I realized that I should have been more cognizant of this and prepared something useful to suggest. However, as one of the session aims was to attend to emotion, I recalled Mynard’s (2019) recommendation not to try to fix problems and refocused my attention on prompting Nanako to express herself at her own pace.

Discussion turned to the current state of her study-abroad program and the communication students were receiving. Reflecting on my previous session, I avoided trying to force an “a-ha moment” and limited my responses to repeating, rephrasing, and encouraging.

Broadening perspectives

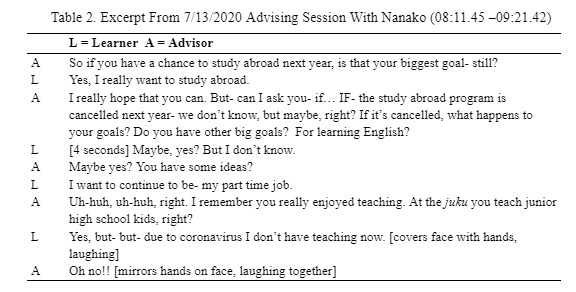

It was clear to me in the previous session that as she had worked to qualify to study abroad, Nanako had begun developing an awareness of her learning trajectory, was visualizing her growth and progress, and had a concrete goal. I had no difficulty feeling and expressing empathy for her feeling robbed of that goal. Still, I was concerned that the session risked devolving into unproductive wallowing. In the transcript contained in Table 2, I attempt to articulate that although the current situation is temporary and that circumstances will likely change, it may be valuable to consider other benefits of successful language learning and identify additional long-term goals. However, this exchange revealed further COVID-related disappointments.

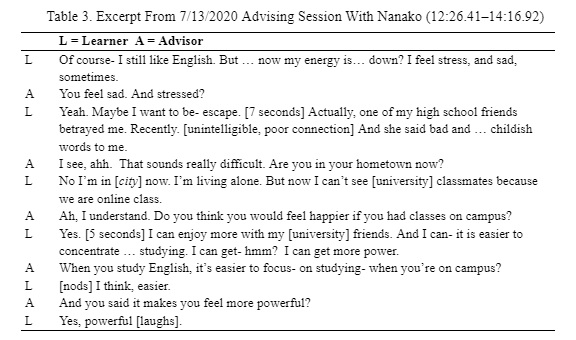

Though we laughed together, there was no question that Nanako found herself in an upsetting situation. Her unemployment, another consequence of the pandemic, had removed another immediate source of motivation and enjoyment from the learning process and represented another setback. We discussed her teaching job further; a more positive discussion opened up around her boss’s promise to rehire her in the future. Nanako volunteered that although she was not sure her long-term goals included teaching, looking forward to working at the cram school helped to lift her spirits. I commented that I was glad to hear that despite her temporary difficulties with motivation, she still enjoyed language learning. Her response below, in Table 3, led us to a more direct discussion of Nanako’s preferred language learning environment.

When the discussion turned to feelings of isolation and separation from family and friends, it became apparent that the reason for Nanako’s difficulty with motivation was less about study abroad specifically and more about human needs going unfulfilled in the wake of the pandemic. Having undertaken to view this session through the lens of positive psychology, I found parallels emerging between Nanako’s flagging motivation and Seligman’s (2012) PERMA framework describing how highly satisfied, flourishing people routinely draw strength from:

- Positive emotion: regular, repeated experiences of positive affect

- Engagement: absorption in chosen activities to the point of forgetting oneself

- Relationships: positive, healthy, and supportive connections with others

- Meaning: a greater purpose to one’s effort

- Achievement: success in pursuing and attaining goals.

I took a mental inventory of Nanako’s struggles. Rather than experiencing positive emotion, she felt sad and stressed. She felt that she engaged with study materials more fully in the classroom than at home. Her relationships with old friends were shaky, and she was isolated from family and her new classmates. Feeling meaning and purpose in teaching English to younger children was put on hold when her job hours were cut. Her sense of achievement was muted by potentially losing the opportunity to study abroad. Each of PERMA’s factors was, for Nanako, in some way diminished over only a few months.

Considering Nanako’s difficulties more broadly, I felt apprehensive about my ability to direct the discussion back to language learning. Simply returning to learning strategies felt obtuse; moreover, I realized that I had selected the Goal-Setting Pyramid” ahead of time purely because it was familiar and felt “safe” rather than necessarily valuable for Nanako. Recognizing this short-sightedness, I considered other tools that might be appropriate and accessible on short notice.

Narrowing focus

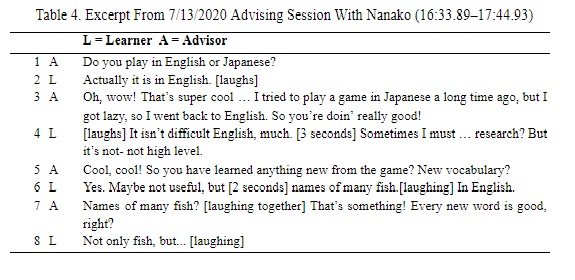

Seeking some light in the discussion, I asked Nanako directly, “What makes you happy right now?” After some thought, she asked whether I was familiar with “Atsumori” (Atsumare Doubutsu no Mori, the video game “Animal Crossing: New Horizons”). I answered that I was, and I could intuit the attraction for Nanako during this difficult time. Its “life simulator” gameplay loop, in which the player is tasked with building and managing a small village while befriending cute animals, provided, at least digitally, simple experiences of positive emotion and engagement alongside simulated relationships and quantifiable achievements—virtual PERMA, minus the “meaning.” My attempt to link her chosen escape to some real-life purpose can be seen below in Table 4.

I felt thankful for the opportunity to link language learning and Nanako’s gaming hobby. As the discussion continued with a brighter tone, I was reminded of the “happiness journals,” simplified and adapted versions of the gratitude journals associated by Flinchbaugh et al. (2012) with reduced stress and outward expressions of well-being, that I had used with Nanako’s class in the previous year. In these journals, learners were asked to list three “good things” they noticed each week alongside something interesting they had learned outside of class (see Appendix), with the aim of reinforcing the satisfaction that comes with independent learning by connecting it with recursive experiences of positive emotion. Nanako being already familiar with the tool, I saw value in reintroducing it.

Future vision

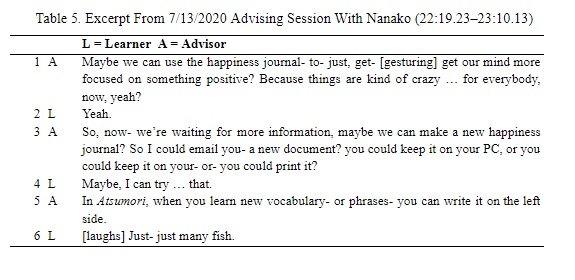

Nanako told me that although she no longer had the journal from the previous year, she remembered using it. I told her that while I had no immediate solutions to her larger concerns, perhaps we could use the journal to keep good things in mind under challenging circumstances.

Final ReflectionThe end of the exchange transcribed in Table 5 marked what felt to me like a sigh of equal parts relief and exhaustion. After discussing Nanako’s frustrations, we had discovered a small bright spot; I did not feel inclined to press or probe further. I reminded myself to feel comfortable with silence and to give Nanako space to express other concerns and feelings; mostly, I hoped she felt she had been heard. Before finishing the session, she committed to using the happiness journal once a week by documenting one new English word or phrase learned while gaming alongside three “good things” that she noticed. Following the session, I emailed her a new journal. In reply, she thanked me for taking time to speak with her and expressed feeling more positive after our session.

While this session presented its own challenges, I was pleased to realize that the feelings of inauthenticity I had experienced in the previous session were entirely absent. In discussions with other novice advisors about feeling greater authenticity, we considered the delicacy of working with real advisees as part of our advising training. If new advisors are preoccupied by checklists of strategies to practice or pressure to force epiphanies and a-ha moments—needing to have something to show for their work—they may inadvertently distance themselves from their advisees.

Fortunately, by engaging in dialogue I felt was more intentional, I found that I was better able to forget myself. Rather than seek openings to use individual strategies, I focused on the overall tone and my advisee’s self-reported emotions, and the strategies—repeating, rephrasing, empathizing, mirroring, complimenting—emerged organically. Kato and Mynard (2016) remind developing advisors that although “we might frequently deal with the emotional side of language learning,” we are not therapists (p. 270). I felt that I managed, colloquially speaking, to “stay within my lane” relying on basic advising strategies to guide discussion of Nanako’s reported loss of agency and difficulty with overall life satisfaction. Though I had not planned to approach the session with PERMA in mind, I found that I felt more grounded when allowing myself to lean on my existing research interest in positive psychology. Through reflection in action, applying the familiar lens of PERMA to the unfamiliar concepts and models discussed in my advisor training helped me to feel more authentic and competent in my new role.

I realized early that I had sabotaged myself by preemptively selecting an advising tool to recommend; it had been thoughtless to presume that what had worked previously would be appropriate for my advisee’s needs. I felt that as Nanako’s long-term goals were in flux, she would have difficulty identifying intermediate objectives. I was pleased not to abandon tools entirely, though I ended up relying on material of my own rather than a more thoroughly vetted resource. Although our action plan going forward was simple, it seemed clear that raising awareness of experiences of positive affect—and encouraging Nanako to link them with aspects of language learning—was perhaps the most fitting and least demanding way forward for a high-achieving learner in danger of burnout.

I look forward to seeing Nanako’s progress with the happiness journal and to a follow-up discussion with her in COVID-19’s aftermath. For me, placing the advisee first and attending to her overall sense of well-being, while also drawing on my genuine research interests, was key to managing my insecurities and shedding the self-doubt I carried through advising training activities. I intend to remain mindful of this and other lessons learned in these initial sessions as I continue my transformational journey from teacher to advisor.

Bio Data

Jason R. Walters is a lecturer and Assistant Director of the Core English program at Nagoya University of Foreign Studies and has lived in central Japan since 2009. His primary research interests include learner autonomy and self-access learning, native speakerism in Asian EFL education, and practical applications of positive psychology in the classroom. <jwalters@nufs.ac.jp>

References

Fansury, A. H., Januarty, R., & Ali Wira Rahman, S. (2020). Digital content for millennial generations: Teaching the English foreign language learner on COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Southwest Jiaotong University, 55(3), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.35741/issn.0258-2724.55.3.40

Flinchbaugh, C. L., Moore, E. W. G., Chang, Y. K., & May, D. R. (2012). Student well-being interventions: The effects of stress management techniques and gratitude journaling in the management education classroom. Journal of Management Education, 36(2), 191-219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562911430062

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning (1st ed.). Routledge.

Mynard, J. (2018). Still sounds quite a lot to me, but try it and see: Reflecting on my non-directive advising stance. Relay Journal, 1, 98-107. https://kuis.kandagaigo.ac.jp/relayjournal/issues/jan18/mynard/

Mynard, J. (2019, October 21-22). Emotional dimensions of language learning: A new era of self-access [Conference presentation]. Encuentro de Centros de Autoacceso de la Universidad Veracruzana, Xalapa-Enríquez, Ver., Mexico. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jo-Mynard/publication/336730468_Emotional_Dimensions_of_Language_Learning_A_New_Era_of_Self-access/links/5daf854192851c577eb9a615/Emotional-Dimensions-of-Language-Learning-A-New-Era-of-Self-access.pdf

Seligman, M. (2010). Flourish: Positive psychology and positive interventions. In M. Matheson (Ed.), The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, 31, 31-243. University of Utah Press.

Seligman, M. E. (2012). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

[Appendix]

Dear Jason,

Thank you very much for sharing your insightful reflection on your advising sessions with Nanako. Your question to Nanako, “What makes you happy right now?” was indeed a powerful question and it seemed to set a new positive tone for the advising session. I feel that there are quite a few learning obstacles that students do not have control over and turning their minds to positive in these situations is challenging, but you accomplished it in such an authentic manner. Also, it is great that you and Nanako have developed a strong connection where she can show you her true self.

I agree with you that authenticity and natural flow are essential in advising sessions. In this particular one, you described that introducing the advising tool, Goal-Setting Pyramid, would have made it inauthentic. However, I got the impression that you are still eager to prepare for an advising session ahead of time. Is it true? Are there ways to prepare for an advising session in advance without making it inauthentic? What would be a way to introduce advising tools more effectively? Is there anything that you would do differently if you could have done the same session again?

As for the paper, I personally felt that there were two different purposes: One to analyze Nanako’s narrative by using PERMA framework and another to analyze your advising. Both would be great papers:)

Thank you again for sharing your experiences!

Dear Satoko,

I appreciate your having taken the time to read my reflection on my experience advising Nanako, and am grateful for your thoughtful comments. As you know, I continually struggle with the idea of balancing preparation with improvisation- what’s authentic, and what is scripted?

You mentioned that “I described that introducing the advising tool, Goal-Setting Pyramid, would have made it inauthentic,” and ask whether there are “ways to prepare for an advising session in advance without making it inauthentic.” I should perhaps have made clearer in the text that there is a meaningful distinction between inauthenticity and “feelings of” inauthenticity. I don’t know that I feel preparation would have made the session (or my approach) inauthenic- there is a lot of value, I feel, in preparing resources, tools, and the like, ahead of time. To clarify, my difficulty with prepared material was very much a result of my own insecurities and inexperience with the tools advising strategies.

In some ways, this is analogous to my experience, years ago, as a new classroom teacher. The students, the environment, the demands of the job- all were new to me. My early lessons were planned in excruciating detail, down to the minute, all materials were created long ahead of time- my classroom presence was nearly scripted. While comprehensive prep and planning helped me to feel that the tasks were manageable, my early lessons were overly rigid and lacked room for improvisation, adaptation, and even personality. Of course, over time, greater familiarity with my students’ needs, my toolkit of resources, my own sense of presence, and classroom management techniques, I found myself much more comfortable working “in the moment” and allowing things to remain fluid. While I have never stopped preparing for my lessons, the preparation is “macro” rather than “micro”- and I am able to draw on years of experience when adjusting my approach to the needs of specific students or classes.

Having had this experience in the classroom, I felt discomfort overpreparing to balance my lack of experience- engaging knowingly in the “fake it till you make it” approach. My limited opportunity to conduct advising sessions has meant a slower development process than I experienced as a classroom teacher, but I am confident that the instincts, awareness of an advisor will proceed in much the same way. As for preparing for advising sessions in advance, the hurdle, I think, is to overcome the gap between preparing “for me” and preparing for the learner- no doubt, this will come with experience.

Thank you again for your thoughts on the reflection- I hope to hear more about your early advising experiences some time as well!

Best,

JW

Dear Jason,

Good article. I concur with Satoko’s comments a great deal. I really liked your use of PERMA and it is a good tool indeed. Your sensitivity with your advisee inspired me. I think probably many teachers have recognized the zoom fatigue by now in many of our students and perhaps might direct more of their students (and often themselves) to the use of happiness journals and more meaningful activities to appreciate living in these challenging times.

As an advisor in training myself, your self-doubts about what strategies to use ring true and remind me again that it is all about the advisee, not our techniques. Maybe teachers should be writing happiness journals as well!?!

Looking forward to reading more of your work and learning from you!

Dear Tim,

Thank you kindly for your comment. Having learned a great deal from you about using learning histories, action logging, “ideal self” meditations, and the like, to give learners a voice, it means a lot that you found value in my experience. You have always led by example, and though my opportunities to advise have been limited, I often draw inspiration from your words when engaging with my learners one-on-one.

You mention seeing value in having teachers write happiness journals- as a teacher who regularly writes in a happiness journal, I can confirm that it is a good use of my time, both for me and for my students. Perhaps I should try some action research with my current lecturer team!

Thanks again for reading (and for your outstanding workshops this past weekend). I truly appreciate your support!

Best,

JW