Scott J. Shelton-Strong and Jo Mynard, Kanda University of International Studies, Chiba, Japan

Shelton-Strong, S. J., & Mynard, J. (2018). Affective factors in self-access learning. Relay Journal, 1(2), 275-292. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010204

Download paginated PDF version

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

In this paper, the authors will give an overview of a course that helps learners to develop self-directed learning skills, focusing specifically on the ways in which the course addresses the affective dimensions of learning. Numerous studies have shown that the affective state is one the most important aspects of learning, yet least understood by students. Developing an awareness and control of affective factors is approached in several ways at the authors’ institution. For example, the course incorporates activities designed to raise awareness of affective factors while also engaging learners in social interaction with others; individual advising sessions often focus on feelings and psychological factors; a guided reflective journal asks learners to monitor their motivation and emotions; and the self-access centre provides affective support in the form of worksheets and leaflets. This paper will include a focus on examples of course activities and students’ work, followed by a discussion of the effectiveness and challenges of the practical interventions.

Keywords: affect, self-directed learning, emotions, language learning, self-access

The term ‘affect’ incorporates a wide range of mental phenomena including moods, emotions, and feelings and is an under-researched area of language development (Oxford, 2011, 2017). Forgas (2000) distinguishes moods and emotions by describing the former as being less intense and more enduring, while the latter appear to be more sharply defined, intense and enjoy shorter life-spans. Affective states, of course, extend to and include both extremes of positive and negative feelings. These have been mapped to the different ways a person might respond to the loss or gain of something of value, their reaction to a perceived threat, or aspiration towards achieving that which is valued (van Deurzen, 2012). Affect and cognition have been identified as interlinked and interdependent (Duncan & Barret, 2007) with each having a naturally significant effect on the other. Affective factors can have an impact on many of the roles we undertake in life, and are particularly salient in areas in which we may feel vulnerable, or which require a deep emotional investment. Learning a second or additional language can be considered to be one of these areas, as affective issues can influence a learner’s motivation, confidence and drive to remain committed to this lifelong endeavour, particularly in the early stages.

This paper introduces an approach to fostering an awareness of affect and a familiarisation with a range of tools which language learners might find useful to manage changing moods and emotions, and thus have an impact on their approach to, and success in, language learning related activities (Oxford, 2017, p. 213). To do this, we will examine a self-directed learning course which we offer to students as a credit-bearing elective, which is called the Effective Learning Module (ELM). This course is completed independently by students outside of the classroom, and incorporates written and face to face advising as support.

We will begin by providing an overview of the context within which our work as Learning Advisors (LAs) and this course are situated, and discuss our reasons to support a focus on affective issues in our work. This will be followed by a brief overview of our self-directed learning courses, and an in-depth look at ways in which we attend to affective factors on these. We will then present examples of the tools, course materials, and activities we use, as well as share an example of a student’s work and related reflections. Finally, we will discuss our views on the effectiveness and challenges involved in embedding a focus on affect into such a course.

Context

The context for this paper is the Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) in Chiba, Japan where we work. KUIS is a small but progressive, private university specialising in international languages and cultures. The SALC provides our students access not only to a variety of resources, but also to advising sessions, self-directed learning courses, learning communities, learning spaces and focused workshops. KUIS is a unique university dedicated to language learning, and has approximately 4000 students majoring in different languages. In addition, all undergraduates are required to take English courses. The SALC is now in its third metamorphosis, continuing to develop from its beginnings in the year 2001. Currently, although SALC use is optional, we have approximately 1000 student visitors per day, and in this context, our work with these students takes place primarily outside of the classroom. Learner autonomy, in this environment, in part, is fostered through reflective practice and dialogue, which focuses on the development of the skills and mindset necessary to encourage lifelong learning. The concept of community is highlighted, as we strongly believe that the social dimension of learning has an important role to play. As LAs we are dedicated to promoting language learner autonomy, and the SALC mission is as follows:

The SALC aims to foster lifelong learner autonomy as an international community by empowering learners to engage in reflective practice and take charge of their language learning. (Mission Statement, SALC Handbook, 2018)

Focus on Affect

One of the reasons we focus intentionally on affect is that three of the core objectives we have for our learners are influenced either directly or indirectly by affective factors.

Learner objectives influenced by affective factors:

- Becoming more aware and in control of learning processes

- Achieving language-learning and other goals

- Becoming confident language users

Addressing the affective dimension in our work, factors relating to moods and emotions, allows us to engage with our students holistically, rather than responding to them simply as “language learners”. Researchers have explored the connection between affect and cognition (Schunk, Pintrich, & Meece, 2008) and there is a growing body of evidence showing the influence of affect on attention, memory, thinking, associations, judgments and making appropriate emotional responses (Forgas, 2000). Clearly, if left unattended, negative emotions and moods can have a negative impact on learning processes, and influence levels of motivation and confidence, for example. By attending to affective factors, intentionally, we feel we are better able to deliver the kind of support our students need to reach their full potential as language learners, and as members of their learning community. Oxford (2015) refers to emotions as an “amplifier, which provides energetic intensity to all human behavior” (p. 371) and that “knowing that emotions can be managed, controlled, shaped, and transformed makes the learner less of a purely passive recipient and more of an agent in the emotion game” (p. 386). Indeed, there is growing interest in the field, with evidence from research studies demonstrating that emotion, learning and performance are directly and closely interrelated (Oxford, 2017).

Advising in Language Learning

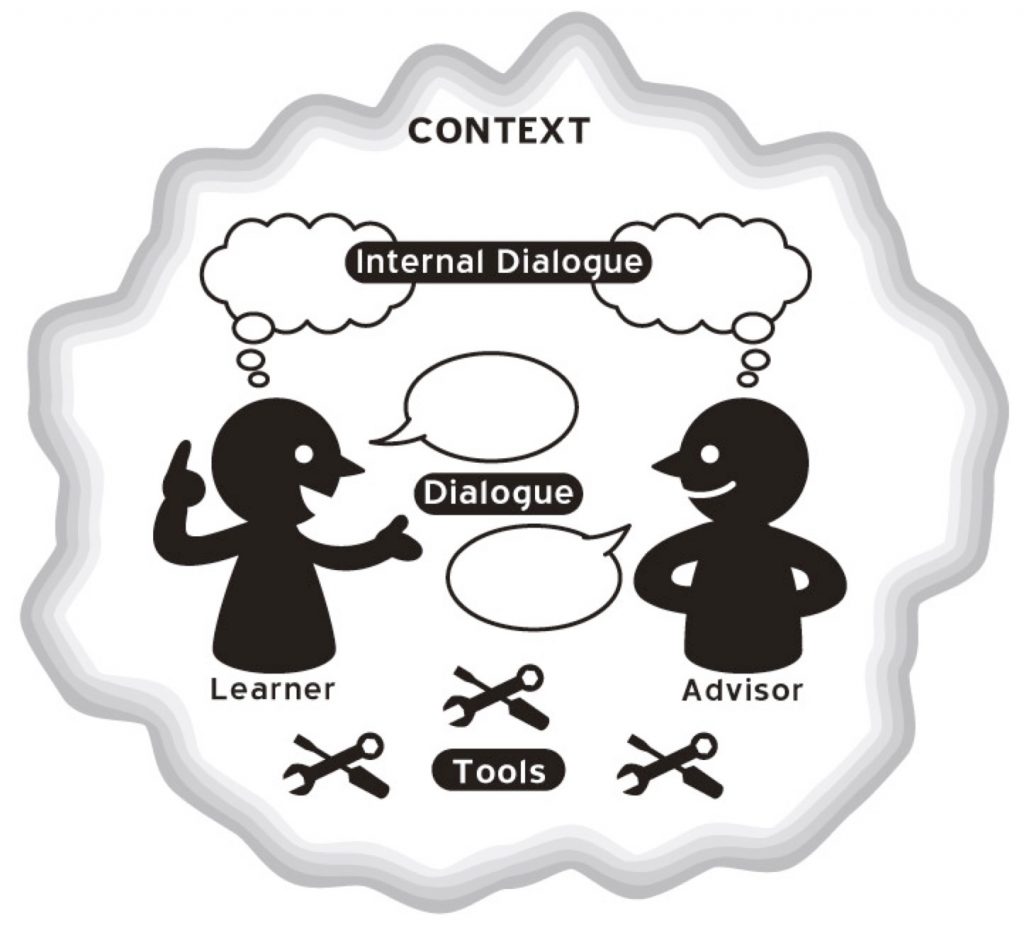

We define advising to be ways in which an advisor works with an individual learner in order to promote language learner autonomy (Carson & Mynard, 2012). To do this, an advisor uses specific discourse (dialogue) and tools. The Dialogue, Tools and Context Model of Advising (Figure 1) is informed by sociocultural views of learning. The purpose of the dialogue is to help the learners to reflect deeply, become aware of the learning process, make connections and ultimately manage their own learning processes (Kato & Mynard, 2016). This dialogue might be supported by a number of tools that form part of our courses and are also available in the SALC.

Figure 1. The Dialogue, Tools and Context Model (Mynard, 2012b, p. 33)

Advising normally takes place as face-to-face, one-to-one dialogue, but it can also occur in asynchronous written form which is not only convenient for reaching many learners regularly, but also has been shown to activate metacognitive processes and have an impact on learning processes (Mynard, 2012a). The self-directed learning courses in our context are supported primarily through written advising.

Self-Directed Learning Courses

The modules and courses we offer are electives designed to help learners develop the capacity and the skills needed for effective autonomous learning. The ELM, for example, is worked on independently, outside of the classroom, with the support of a learning advisor through a weekly exchange of shared reflections and response. In this way appropriate guidance and support are provided through focused interpersonal communication and interaction in the form of an ongoing intentional reflective dialogue (Kato & Mynard, 2016).

These courses are facilitated by LAs where a variety of tools are introduced with the aim of raising self-awareness, dealing with affective issues, and focussing the student on his or her needs, learning goals and learning processes.

Through self-directed study, self-analysis and reflection, our students learn about and experiment with these tools, learning strategies, and resources to aid them as they work towards achieving self-identified personal learning goals. Some of these tools and strategies relate directly to affective factors, as they experiment with confidence building, learning to monitor motivation, identifying ways to manage anxiety, and coping with setbacks, for example. These are incorporated directly into the module content of the ELM and are further explored and supported in face to face advising sessions at a learner’s request.

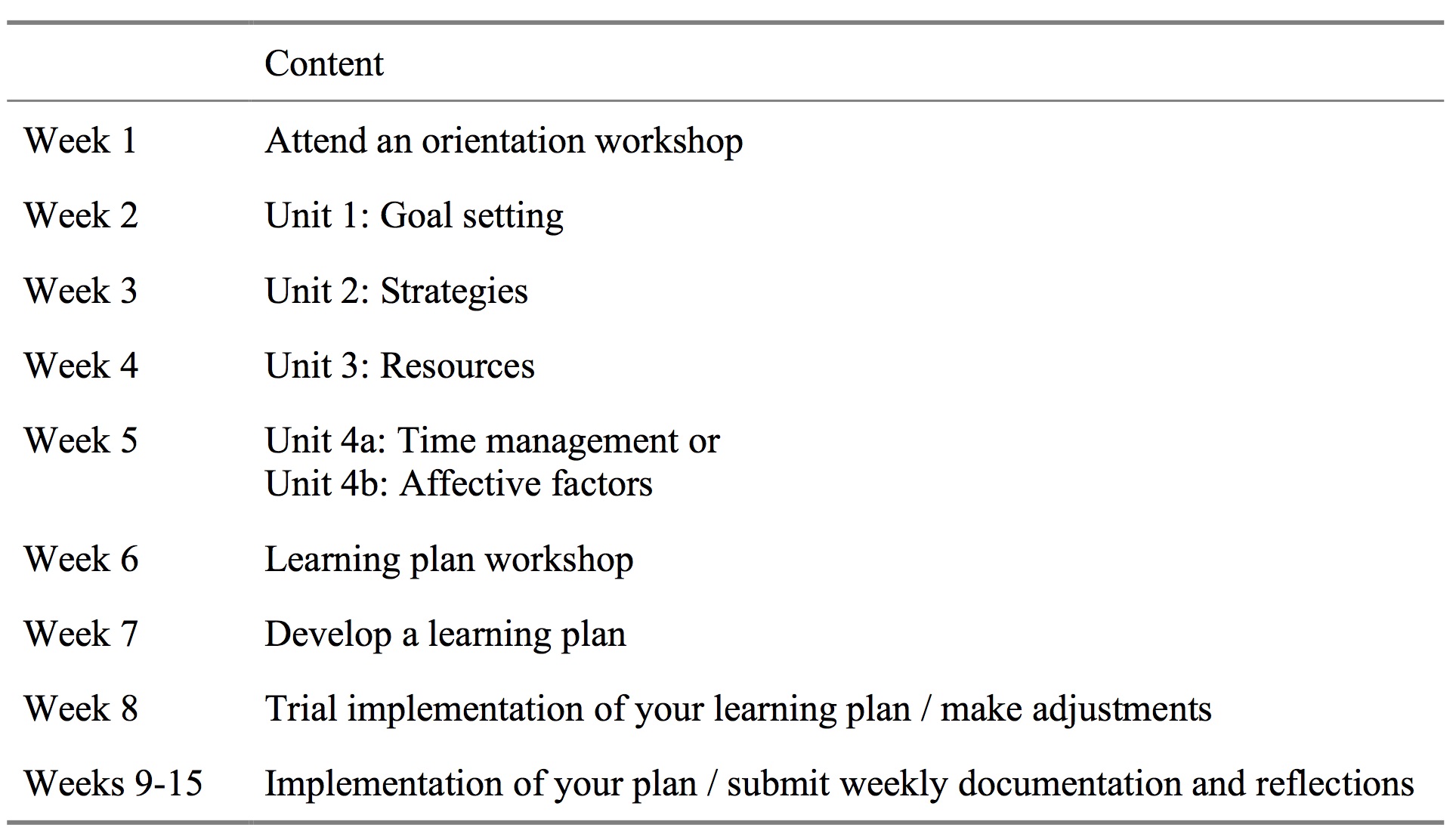

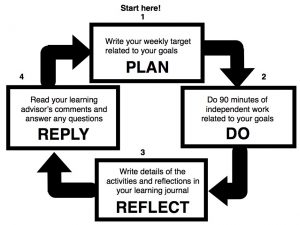

In the first five weeks of the course, students are introduced to self-directed processes in order to help them to develop the skills and awareness of how to take charge of their learning (see Table 1 for an overview of the course). They then formulate a personal learning plan and spend the remainder of the course implementing the plan, focussing on personally relevant language and content goals. The process is based on Kolb’s (1984) experiential cyclical model involving planning, doing and reflecting (Figure 2).

Table 1. Course Overview

Figure 2. Plan – Do – Reflect – Reply Weekly Cycles (based on Kolb, 1984)

Figure 2. Plan – Do – Reflect – Reply Weekly Cycles (based on Kolb, 1984)

Specific Ways We Attend to Affective Factors in Our Courses

The SALC curriculum is underpinned by a set of guiding principles (see Lammons, 2013 for details) which were established when The SALC team evaluated and redesigned the curriculum for SALC self-directed learning courses. This means that even if the team changes or we make changes to the materials, we still maintain key features of the course. The first principle is that students should learn about socio-affective skills to optimise their learning.

There are six ways in which the courses are designed to address the affective dimensions of language learning. The first way we focus on affect is to introduce the term “affect” and Unit 4b is called Affective Strategies. The term is normally unfamiliar to students, but by explicitly teaching it to them we add to their metalanguage, with affect becoming a normal area of discussion about learning like just “goals” or “resources” or “learning strategies”.

The second way we focus on affect is that in this unit, we specifically introduce awareness-raising tools and strategies related to confidence, motivation and anxiety. In order to do this, we draw upon the recent relevant literature in order to understand psychological factors that greatly influence learning. Thirdly, each unit involves discussing ideas with other learners in order to incorporate social processes so that learners do not work in isolation. For example, we ask learners to interview their friends about what they do to maintain a positive attitude for learning. This kind of activity highlights that it is normal for people to need to regulate their emotions when learning. In addition, students have the opportunity to learn from others.

Next is interest which is considered here as an example of a positive emotion (Fredrickson, 2001). Oxford and Cuéllar (2014) used an adapted version of Seligman’s (2011) PERMA (positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning and accomplishment) in a study on resilience in language learning. They found that positive emotions such as interest and happiness in learning were prevalent in successful learners. Applying the Self-Regulation of Motivation (SRM) Model (Sansone, 2009; Sansone & Thoman, 2005) in longitudinal studies in our SALC (McLoughlin & Mynard, 2014; Mynard & McLoughlin, 2015), we know that interest development is a key way in which our self-directed learners sustain their motivation for learning. Setting goals is usually not enough to sustain motivation for long term language study, so we ensure that there is a focus on interest. This idea is connected with the goals of positive psychology to apply positive emotions to everyday life, in order to build resilience, to thrive, and to lead a meaningful life (Fredrickson, 2001; Ibrahim, 2016; Seligman, 1991).

Next, at the end of each week during the implementation portion of the course, students answer guided reflection questions, such as “How satisfied do you feel this week? Why? How was your motivation this week? Do you want to change anything?” The purpose of this is to tap into their feelings and motivations so that they are engaged in the process all the way through. Constant reflection on the motivational processes contributes to self-regulation (McDonough, 2001).

The 6th way we focus on affect is through the written dialogue. LAs often focus on affective factors and notice when a learner seems anxious, tired, or burned out, and reaches out to them through the dialogue, introduces some strategies or encouragement, or suggests that they make an appointment. Students often open up in written dialogues in ways that they might not in face-to-face advising. In one of our studies (Thornton & Mynard, 2012), we analysed written advising and found that more than one third of advisor comments in modules were related to affect. In another study, we confirmed that students value all types of comments made by learning advisors in the written advising dialogue, but particularly appreciate affective comments (Mynard, 2012a).

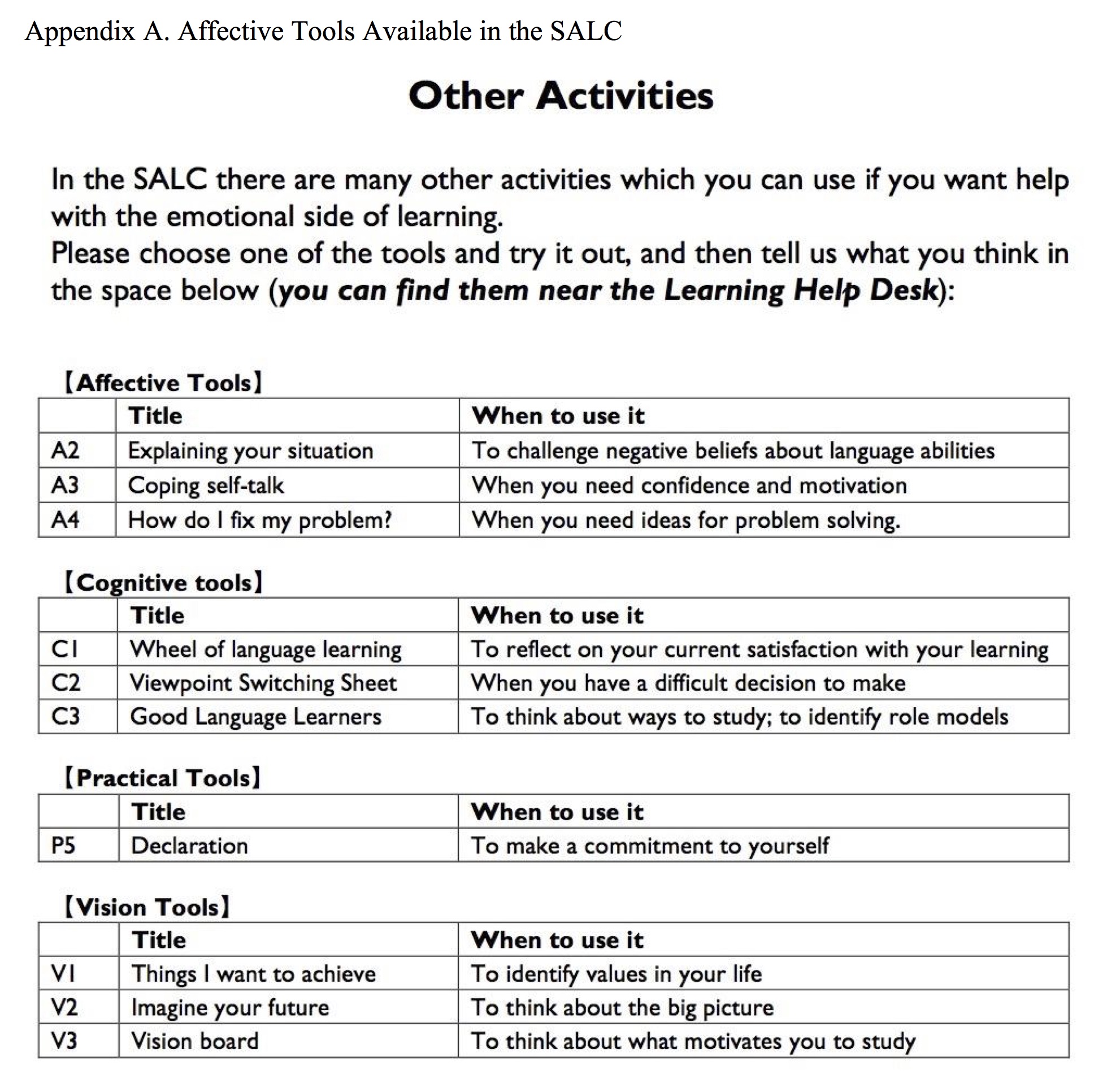

In addition to embedding these activities into our courses, various affective tools are made readily available in the SALC for learners, teachers and advisors. For example, the motivation graph (Kato & Mynard, 2016), or visualisation tools such as “My Future L2 Self” (Dörnyei & Hadfield, 2014, p. 26). These have either been developed in house, adapted from other sources, or borrowed from other fields such as coaching and Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT). Many of these tools are also used in workshops or class activities.

Examples of Affective Tools

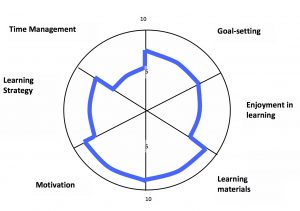

The Wheel of Language Learning

One tool that we find particularly useful to help learners visualise various aspects of the learning process was adapted from coaching by Yamashita and Kato (2012). We normally introduce this tool at some point during the implementation phase of a course. Each segment could relate to an aspect of the learning process such as goal setting or materials and the learner notes their current levels of satisfaction in this area. This tool is cognitively rich, but linguistically accessible, allowing for deep reflection on the process. Due to the visual nature of this tool, it helps learners to make connections between factors associated with their learning.

This is a completed wheel showing the current level of satisfaction providing a springboard for deeper discussion of the issues, for example, such as how each area might be enhanced.

Figure 3. The Wheel of Language Learning (Yamashita & Kato, 2012, p. 165)

The Confidence-Building Diary

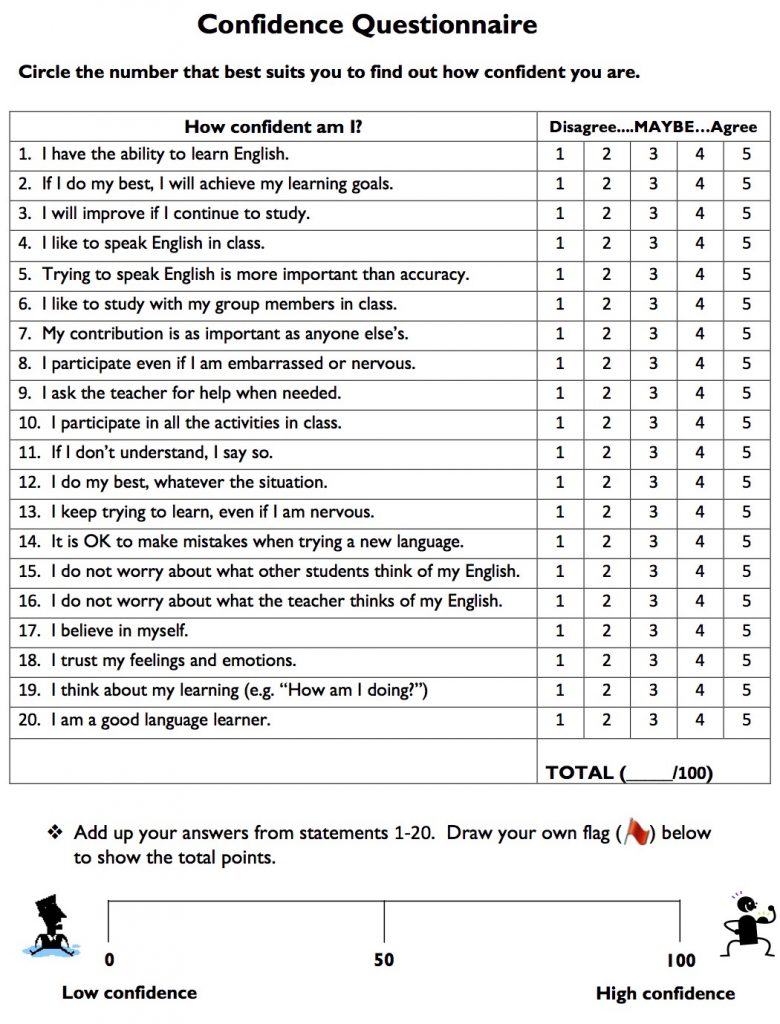

The Confidence-Building Diary is another of the affective tools we use, and is embedded into the Affective Strategies unit of the ELM. The Confidence-Building Diary is preceded by a questionnaire (Figure 4) where the student reflects on their perceived level of confidence by responding to a set of questions related to self-confidence in language learning, before rating this on a percentage bar. There are a total of 20 questions, all of which relate to the question: “How confident am I?

As reflection is clearly connected to self-awareness and autonomy, opportunities for this are consistently integrated throughout the course materials.

Figure 4. Confidence Questionnaire (adapted from Finch, 2004)

We will now share a brief outline of the learner’s profile whose work from this unit we will be examining. A pseudonym has been used to protect her privacy. Miki is an 18-year-old first-year undergraduate, and an English major. Her interests include reading, music, baseball and calligraphy, and her future goal is to work as a flight attendant. She has demonstrated a keen interest in her studies and her participation in the ELM. Miki showed a relatively high level of self-reported confidence, rating hers at 70% as a result of the questionnaire.

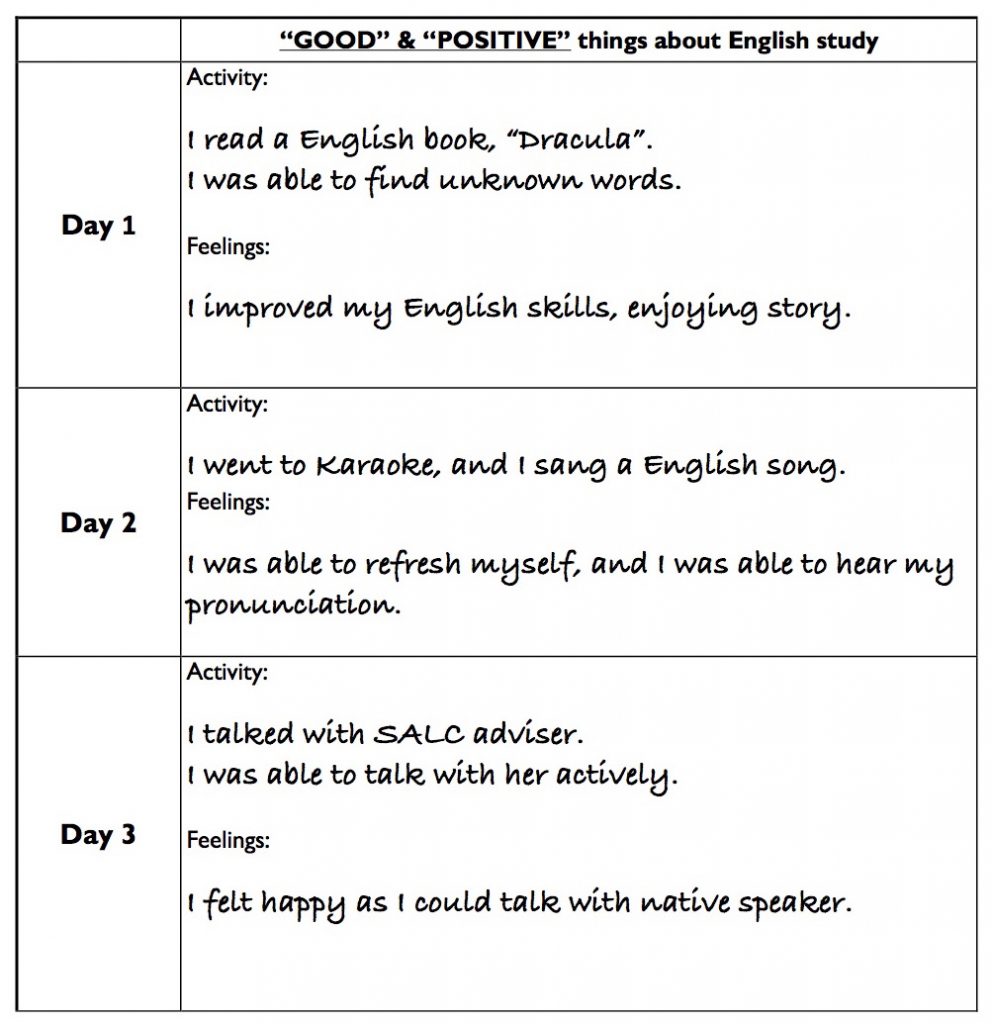

The aim of the Confidence-Building Diary is to encourage students to reflect in a positive frame of mind on their activities as language learners, over a period of three or more consecutive days. The aim is to not only encourage self-awareness, but also to foster a positive growth mindset (Dweck, 2012), and introduce a useful tool for monitoring confidence levels and motivation that they can return to and use again at any point in the future. The responses we receive from students here are often of a deeper, more personal nature than those in previous reflections, and which often point towards the development of metacognitive awareness, examples of which we will see in the following sections.

Figure 5 is a copy of Miki’s completed Confidence-Building Diary, as she focuses on three distinct activities which she engaged in on three different days, and how she felt about these. Her work shows what appear to be indicators of purposeful, agentic action, and the positive feelings these produced, as Miki reflects on her experiences. Here she focuses concretely on what she has done, and reflects on these activities in a positive light.

Figure 5. Miki’s Confidence Diary with the Activities Chosen and Feelings

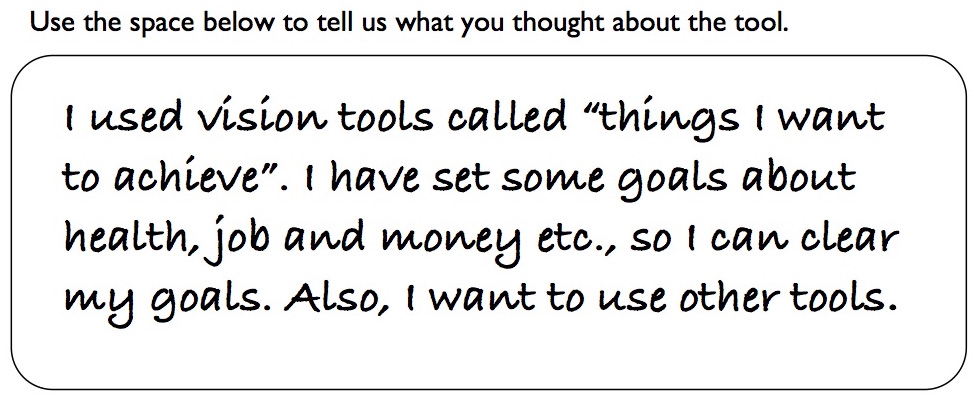

Following the completion of the diary, students are invited to explore the wider range of tools we make available in the SALC (Appendix A) and to choose one of these to experiment with, and reflect on. We can see that Miki chooses a vision-orientated tool, in which she envisions her future based on personal life goals. It is also significant to note that this experience has encouraged her to experiment with other similar tools in the future.

Figure 6. Miki’s Reflections on Using the Vision Tool

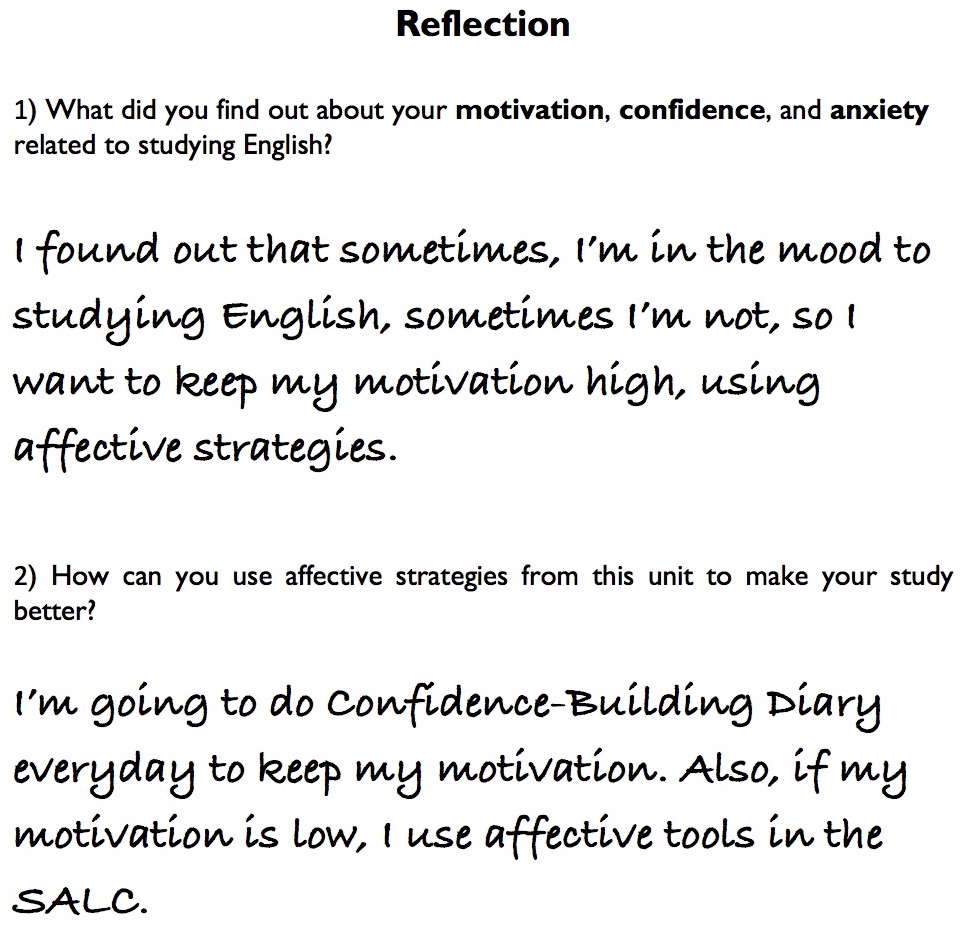

At this point, students are asked to summarise and evaluate their experience with the Confidence-Building Diary, and add suggestions they might have for future action, to help maintain a positive mindset.

The first question Miki is asked to consider is whether the Confidence-Building Diary had motivated her, and to think about why this might be. To this she responds, “Yes, it did. It’s because I was able to recognize my results by writing them. Also, I thought that I can improve my writing skills by writing at the same time.” Following this question, she is asked to think about what she could do other than the Confidence-Building Diary, which could help her maintain a positive attitude towards learning English. To this Miki replies, “If I achieve my goals, I reward myself. I think the rewards give me pleasure, so I can keep my motivation.”

Here, Miki appears to reflect deeply, showing that she recognises the value of keeping the diary, and considers how she can reward herself to maintain motivation. Again, this appears to indicate that she is beginning use a degree of metacognition to assess her ability to play a more active role in her own learning processes and manage her motivation.

When asked to reflect on what she had discovered about herself in terms of how she manages affective issues, there is further indication that Miki is becoming increasingly self-aware as she recognises how her own moods can change and how she can take a more active role in maintaining her motivation. She continues to exercise a high level of agency by suggesting she will continue to keep her Confidence-Building Diary. In addition, she notes that if her motivation is low, and if she feels that, then she is now aware of the affective tools and strategies that she can use (in the SALC) to help herself. We see in the final two reflective questions of the unit (see figure 7) indications of Miki learning to take charge and assert herself in order to manage her moods and emotions in relation to her language learning experience.

Figure 7. Miki’s Final Reflections

In summary, here we have seen an example of how a student has engaged with the Affective Strategies unit of the Effective Learning Module. Within her responses, we notice how an explicit focus on confidence and positive thinking has generated insightful reflections. These reflections appear to suggest the development of (further) metacognitive awareness of the role she herself can play as an active agent in her own learning experience.

This development stands out as one of the affordances that including a focus on affective factors can have in a language learning context. This can be particularly relevant in a self-directed learning course such as the one we have discussed, which allows for limited face to face contact with the facilitating learning advisor. The section that follows will examine in greater depth further potential benefits and challenges a focus on affect can generate.

Benefits and Challenges of Embedding Affect into a Self-Directed Learning Course

In terms of benefits, talking about affect and learning makes it clear to students that it is a normal part of the learning process, like choosing good resources and appropriate strategies. Secondly, students are introduced to tools and strategies that they can use throughout their lives as language learners. The activities often lead to deeper connections and empathy between learners and advisors (and between learners) often leading to follow up and ongoing advising sessions. Being able to offer face-to-face support for learning is not always possible, but we can reach many more learners through the activities and written advising in these courses, ensuring that everyone focuses on this important part of the learning process to some degree.

However, there are several challenges that need to be considered. For example, not everyone needs a focus on emotions at the same time and in the same way. In our courses, we introduce tools at a given time which is not ideal. It is best that students are introduced to tools when they actually need them, but the hope is that they will know that the tools exist when they do need them. Clearly this needs careful research. In addition, deciding which factors to pay attention to, and in what depth might be appropriate could be a challenge. We need to tailor them to our student population, but build in a choice where possible. Finally, not all learners will be prepared to disclose emotional aspects of learning, which we need to respect. In our experience, however, perhaps because of the nature of the course, students really enjoy talking about emotions and learning and find it reassuring that others may also have similar affective issues. Our learners respond positively to opportunities to develop strategies for understanding and managing emotions.

Conclusions

In this paper, we have considered ways in which to embed a focus on affect into a self-directed learning course, and the implications this may have for language learners. We have given some examples of tools that could be used for awareness-raising and strategy-building, and we have talked about the role of advising in this process. From the examples of student work and reflections, it would appear that the potential for raising awareness through an explicit focus on affective factors, such as confidence, can be helpful for learners as they learn to monitor their emotions, and engage with their contribution to their own learning processes. One final point to make is that although we have found that tools can be very useful, it is the combination of the tools, opportunities for reflection, and the dialogue that make these activities particularly powerful, enabling a shift in metacognitive awareness and self-discovery, with this being further developed through face-to-face or written advising.

Notes on the Contributors

Scott Shelton-Strong is a Learning Advisor in the Self-Access Learning Center and a member of the Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education at Kanda University of International Studies in Japan. He earned his MA TESOL (with distinction) from the University of Nottingham, UK. Among his research interests are language learner autonomy, advising, affect in language learning, and the role of psychology in language learning.

Jo Mynard is a Professor, Director of the Self-Access Learning Center, and Director of the Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education at Kanda University of International studies in Japan. She has an M.Phil. in Applied Linguistics from Trinity College, University of Dublin, Ireland and an Ed.D. in TEFL from the University of Exeter, UK. Her research interests include learner autonomy, advising, self-access and affect in language learning.

References

Dörnyei, Z., & Hadfield, J. (2014). Motivating learning. London, UK: Routledge.

Duncan, S., & Barret, L. F. (2007). Affect is a form of cognition: A neurobiological analysis. Cognition & Emotion, 21(6), 1184-1211. doi:10.1080/02699930701437931

Dweck, C. (2012). Mindset: How you can fulfil your potential. London, UK: Constable and Robinson Ltd.

Finch, A. (2004). English reflections: An interactive, reflective learner journal. Daegu, South Korea: Kyungpook National University Press.

Forgas, J. (2000). The role of affect in social cognition. In J. Forgas (Ed.), Feeling and thinking: The role of affect in social cognition (pp. 1-28). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218-226. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Ibrahim, Z. (2106). Affect in directed motivational currents: positive emotionality in long-term L2 engagement. In P. D. MacIntyre, T. Gregersen & S. Mercer (Eds.). Positive psychology in SLA (pp. 258-281). Ontario, Canada: Multilingual Matters.

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective Dialogue: Advising in Language Learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

Lammons, E. (2013). Principles: Establishing the foundation for a self-access curriculum. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(4), 353-366.

McDonough, S. (2001). Promoting self-regulation in foreign language learners. The Clearing House, 74(6), 323-326

McLoughlin, D., & Mynard, J. (2015). How do independent language learners keep going? The role of interest in sustaining motivation. rEFLections: Special issue: Innovation in ELT, 19, 38-57.

Mynard, J. (2012a). An analysis of written advice on self-directed learning modules and the effect on learning. Studies in Linguistics and Language Teaching, 23, 125-150.

Mynard, J. (2012b). A suggested model for advising in language learning. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 26-41). Harlow, UK: Pearson.

Mynard, J., & McLoughlin, D. (2014). Affective factors in self-directed learning. Working Papers in Language Education and Research, 2(1), 27-41.

Mynard, J., & McLoughlin, D. (2016). Sustaining motivation: Self-directed learners’ stories. Proceedings of the 7th CLaSIC conference, Singapore, 217-228.

Oxford, R. (2015). Emotion as the amplifier and the primary motive: Some theories of emotion with relevance to language learning. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 5(3), 371-393. doi:10.14746/ssllt.2015.5.3.2

Oxford, R. L. (2017). Researching language learning strategies: Self-regulation in context (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Oxford, R. L., & Cuéllar, L. (2014). Positive psychology in cross-cultural narratives: Mexican students discover themselves while learning Chinese. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 2, 173-204. doi:10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.3

Sansone, C. (2009). What’s interest got to do with it?: Potential trade-offs in the self-regulation of motivation. In J. P. Forgas, R. F. Baumeister, & D. M. Tice (Eds.), Psychology of self-regulation: Cognitive, affective, and motivational processes (pp. 35-51). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Sansone, C., & Thoman, D. B. (2005). Interest as the missing motivator in self-regulator. European Psychologist, 10(3), 175-186.

Schunk, D. H., Pintrich, P. R., & Meece, J. L. (2008). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Seligman, Martin E. P. (1991). Learned optimism: How to change your mind and your life. New York, NY: Pocket Books.

Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York, NY: Atria/Simon & Schuster.

van Deurzen, E. (2012). Existential counselling and psychotherapy in practice. (3rd ed.). London, UK: Sage.

Yamashita, H. & Kato, S. (2012). The Wheel of Language Learning: A tool to facilitate learner awareness, reflection and action. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds). Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 164-169). Harlow, UK: Longman.

Dear Scott and Jo,

Thank you very much for sharing this insightful article with a lot of practical ideas for language teachers/advisors to take away!

As an ESL lecturer who teaches EAP courses to undergraduate students in different programs, I can relate, from my personal experience, the important role played by affect and mood in affecting students’ motivation and engagement in language learning. In the area of out-of-class language learning which you focus on, I assume the affective states of students play an even more decisive role in determining the success of a student’s language learning journey.

What I like most about this article is how you attempt to connect theories with practice. At the outset of the paper, you discuss the notions of ‘moods’ and ‘emotions’ and the salience of emotions in students’ language learning experience. Then, you put forward two models (the Dialogue, Tools and Context Model and Kolb’s experiential cyclical model) which underpin the course design of a self-directed learning course called the Effective Learning Module (ELM). Particularly, I enjoy reading the case study of how the tools available at the self-access center helped develop positive thinking and confidence of an English-major student.

While the focus of this paper is to showcase how the different tools can be used to develop students’ emotions and metacognitive awareness, I am very interested in reading some examples of written and spoken dialogues between the student and the language advisor, and how those may assist in developing the students’ confidence and motivation in learning a second or additional language. The inclusion of discourse samples and a discussion on how the interplay between dialogues and tools help develop students’ positive affect can provide readers with a better idea of how the Dialogue, Tools, and Context Model can be translated into practice.

One question I have is related to the assessments of the ELM. Since this is a credit-bearing course, I am intrigued to know the types of assessments which facilitate the development of students’ self-directed learning skills and whether the design of assessments has a role to play in promoting positive emotions in students’ language learning experience.

Cheers,

Ivan

Dear Ivan,

Thank you so much for reviewing our paper. We are glad that you found it interesting. It seems like you also understand the importance of affective factors within an EAP context. You write “I assume the affective states of students play an even more decisive role in determining the success of a student’s language learning journey [in out-of-class learning]”. Perhaps they do as often the learners are working alone without a teacher or classmates, so it is so important to understand one’s emotions and the role they play in learning in order to keep going. This may be crucial in class too even where there are other people who can help with motivational factors, but learning still takes place beyond the classroom as well. In addition, students may be dealing with negative emotions inside the classroom (anxiety, boredom, etc.), so the tools we provide to learners outside the class could be useful for all learning situations.

Thank you for bringing up the point of how we assess our students’ performance on the ELM. We will try to touch on this briefly in the final version of the article so that that it is clear to the reader. One credit is earned on completion of the 15-week course using a pass/fail criteria based on two areas, which are broken down into specific components. The two areas are Unit Activities (including Reflections), and the self-directed learning processes the students undertake to complete their weekly units of work. Through the weekly exchanges in a written form of transformational advising between LA and student, the LA takes a continuous assessment approach to evaluate the extent to which the self-directed learning processes and their reflections on this, meet our criteria for a pass grade. On a similar course with a classroom hour included (but nearly identical curriculum) Scott recently piloted a descriptor/band-based self-assessment component where students chose the description that they believed best reflected their performance in these areas, and justified it by writing anecdotal evidence to support their assessment. In this case we do think that assessment can play a positive role and help learners to reflect on the consistency and depth of their behaviours, actions and performance and relate these to assessment to a greater extent than traditional grade based criteria, which they may not see as objective, or which may seem out of their control.

You asked about examples of the dialogue exchanges and how the dialogue contributes to motivation and confidence. These are really fascinating, but would be too lengthy to include in this paper. Actually a lot more work needs to be done to explore the role of dialogue, but you might be interested to see the “Reflective Practice” column in Relay Journal edited by Kie Yamamoto which features insights into advising sessions from many colleagues. Jo (Mynard, 2018) published a paper in issue 1 which explores the nature of the dialogue between the advisor and the learner (as a personal reflective narrative). A description of the full study is given in Mynard (2017) and you can see at the end that participants felt that the module and the advising helped them to achieve their linguistic goals and, in one participant’s case (Emi), to improve her confidence. In short, we know that advising (in combination with tools such as ELM) helps learners with confidence and motivation from our practice and from other (very limited) studies, but we need to be able to demonstrate this through more studies.

Thanks again for taking the time to read and respond to our paper. It has helped us to think about our work from a different perspective. We will be revising the paper to incorporate some of the ideas discussed here.

With appreciation.

Scott and Jo

Mynard, J. (2017). The role of advising in developing an awareness of learning processes: Three case studies. Studies in Linguistics and Language Teaching, 28. 123-161. Retrieved from https://1drv.ms/w/s!AnKDRCjRshligUARpx_ystlJ_nfT

Mynard, J. (2018). “Still sounds quite a lot to me, but try it and see”. Reflecting on my non-directive advising stance. Relay Journal, 1(1), 98-107. (LINK)

Dear Scott and Jo,

I would like to thank you for developing and sharing such an inspiring course that is based on certain theories and models. The applications at the Self Access Learning Centre (SALC) has shifted my perspective as a foreign language instructor as I discovered the practical ways to implement the notion of learner autonomy. In this paper, you went one step forward by dwelling on a neglected area in language learning; affective factors.

As you have elaborated throughout the paper, although affective state is one of the most important aspect of language learning, it is the one that is mostly neglected in traditional schooling. We have the tendency to see our learners simply as language learners, receivers of information. However, when we address the affective states of our learners, we start responding to them as individuals. Learning a foreign language is one of the areas learners may experience changes such as ups and downs in mood, level of motivation and self-confidence. With an explicit focus on their affective states through ELM, face-to-face advising sessions and various tools, learners start to direct their own learning and are encouraged to regulate their emotions, which in turn will affect their learning processes positively due to the close link between affect and cognition (Schunk, Pintrich, & Meece, 2008). The milestone in this process is the constant feedback students go through either by guiding questions in ELMs or the affective tools. Moreover, the tools and the strategies introduced at SALC also promote life-long learning skills as they can refer to these tools and manage their affective state and regulate their own emotions whenever they feel the need to.

The question I would like ask is related to the integration of ELMs into the school curriculum. How effective can it be to implement an adapted version of a similar learning module in the language classroom as it will be the teacher to cater for the language related needs together with the affective states of the whole class rather than a learning advisor?

Another concern of mine is related to the level of language proficiency of the learners. In our context where students attend one year English preparatory program so as to cope with their classes in their departments in an English-medium university, students are expected to improve all four skills simultaneously. They have neither the sufficient amount of time nor the opportunity to focus on one area of language. To me, learner autonomy needs to be fostered even in lower levels of English proficiency so that learners can acquire the notion of self-directed learning and self-regulation. What is more, learners with lower proficiency level are more vulnerable to be discouraged due to affective filters. How effective would it be to adapt such modules in lower levels as well?

As a novice learning advisor in the field, I would like to thank you once again for this comprehensive, thorough study as I will definitely revisit this article to remind myself of the significance of affective factors in learning.

Dear Hülya,

Thank you so much for taking the time to read our paper and to respond. We are glad you found it to be a useful exercise! Your questions and comments have been very helpful for getting us to think about how to respond and how to possibly revise our paper in light of your comments and suggestions.

Firstly, we completely agree with your assessment that learner autonomy and self-directed learning can be fostered with students at lower proficiency levels. We feel that a similar approach to how our modules are put together would work equally as well using simpler language, or even through the use of the L1. However, it is a missed opportunity to develop agency and metacognitive skills in the target language if we avoid using it altogether with this kind of work (of course, this is an ongoing debate – see Kato & Mynard (2016), p. 252-256; Little, Dam & Legenhausen (2017), and Thornton, (2012)). We believe that grading the language while maintaining the purposes we aim to achieve is feasible. To be honest, not many of our students who choose to take the module are proficient speakers of English, and although some can struggle occasionally with the language, they normally manage quite well. For the confidence building diary (CBD) in particular, we think you could make an adapted version with few changes needed. There wouldn’t be any problem with providing a bilingual version of the instructions, but we suggest that keeping the activities and reporting on them in the TL as this is one of the motiving aspects of the CBD that our students reported. How effective it might be might also depends on if they are given a choice to do this kind of activity or not (after it is explained to them) and whether or not they have access to speak to someone who could help them if needed.

Thanks again for your very useful questions! We wish you success in implementing affective factors into your language classrooms in Turkey!

Scott and Jo

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

Little, D., Dam, L., & Legenhausen, L. (2017). Language learner autonomy. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Thornton, K. (2012). Target language or L1: Advisors’ perceptions on the role of language in a learning advisory session. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds). Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 65-86). Harlow, UK: Pearson.