Huw Davies, Kanda University of International Studies

Davies, H. (2019).On advisor education: evaluating departmental training and professional development practices of academic staff in a Japanese university. Relay Journal, 2(2), 271-291. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020203

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

This study is an evaluation of the professional development (PD) programme for learning advisors employed in the self-access centre at Kanda University of International Studies in Japan. The research issue investigated was whether the PD activities of advisors allow them to provide appropriate support to students at the University. The implementation of policies, the people and the setting were all considered in building an understanding of what may make the programme work. The framework used to understand this programme is realist evaluation (Pawson & Tilley, 1997), in which theories related to the initial research issue were refined and developed to offer new perspectives. Results suggest that initial training aids advisors in supporting students, but that future implementation decisions are needed for the mentoring element of the programme and on whether more peer observation should take place. The implication that informal discussion among the workgroup and the freedom to choose personal PD journeys are fundamental drivers of effective practice is a finding that may be applied to other teacher and advisor education settings.

Keywords: professional development, teacher education, realist evaluation, reflective practice

This paper evaluates the professional development (PD) activities of learning advisors in the Self-Access Learning Centre (SALC) at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) in Chiba, Japan. In 2017 the SALC moved to a larger purpose-built location on campus and became a department and research institute in its own right, having previously been a section of a larger institute. Consequently, as well as having a changed status within the university hierarchy, student usage and expectations of the new space are have evolved (see Imamura, 2018), impacting the roles learning advisors are required to perform; this evaluation is therefore timely to ensure that advisors’ PD practices are relevant for the post-2017 SALC. The standpoint taken in this study is that it is vital to connect student learning to the practices and knowledge developed by educators who participate in professional development programmes (Bates & Morgan, 2018; Darling-Hammond, Hyler & Gardner, 2017), because the outcome of PD is not necessarily students receiving support even though it is often the stated purpose of a programme (see Yoshikawa et al., 2015).

This study attempts to achieve the following research aim: to determine how effective the current professional development programme for advisors at KUIS is in meeting their role of providing support to students. In order to pursue this research aim, it is necessary to scrutinise the content of the PD programme, how the programme is implemented, and the impact of the people involved and the location on the programme. Therefore the following research questions are addressed:

- What is it about the implementation of PD policies that makes this programme a success or otherwise?

- What is it about the people and setting that makes this PD programme a success or otherwise?

- What elements does an effective advisor PD programme contain?

This empirical study addresses a gap highlighted by Inoue (2017), who opines that there is insufficient research into PD programmes for advisors in the field of advising for language learning (ALL). Furthermore, by focusing on a departmental workgroup at a university, this ‘meso-level’ research builds knowledge at an under-investigated level of analysis (Trowler, Fangharel & Wareham, 2005, p. 435). This paper reviews literature related to ALL and interdisciplinary PD practices, including language education, counselling, life coaching and medicine. Then the evolution of theories on what makes the programme work is presented, detailing two stages of data collection based on a realist evaluation approach (Pawson & Tilley, 1997). The data consist of an interview with a practitioner to inform about the background of the programme and formulate initial theories, and interviews with four participants in the PD programme (subjects) and one policy maker (stakeholder) – coded first in relation to the initial theories, and secondly to find any emergent themes – to develop these theories. The revised programme theories make up the basis of the discussion and conclusions.

Background

The PD programme for learning advisors at KUIS consists of three mandatory elements. Two of the compulsory PD activities are undertaken by all advisors, namely being involved in the mentoring programme, where new advisors are paired with a more experienced peer, and writing an annual PD report. The stated goals of these aspects of the PD programme are ‘to provide supportive opportunities for the professional development of Learning Advisors while they are working at KUIS [and to] provide a record of professional development for future career purposes’ (SALC, 2017). There are many further optional but expected PD activities for all advisors, which include attending talks by guest speakers and participating in conferences. Additionally, advisors are required to seek out PD opportunities as needed because, as the staff handbook states, ‘Each staff member is tasked to do his/her day-to-day job unsupervised’ (SALC, 2017). Participation in this programme requires advisors to work collaboratively and to be autonomous. The way PD is explained in the staff handbook suggests it is for long-term career development of advisors, yet to be of immediate use it needs to impact student learning in the short term. It is imperative that this research explores the connection between advisor PD and student learning.

The third mandatory programme component consists of training for first-year advisors, which culminates in an observation report. The policy document suggests this programme element is associated with meeting student needs, ‘The purpose of the advising observations is to provide an opportunity for a learning advisor to develop his/her advising skills and to ensure that students are receiving quality advising’ (SALC, 2017). In this setting, giving quality advising means being able to structure intentional reflective dialogue to enable students to gain a deeper understanding of their personal learning style and develop the strategies they need to continue learning effectively beyond their formal education (Kato & Mynard, 2016, p. 6). Although advisors are recruited as experienced teachers with Master’s Degrees, training in advising is necessary. Dialogue between an advisor and a student differs from language teacher to student interactions: in advising learners make the decisions and the advisor acts as a sounding board to encourage reflection (Mozzen-McPherson, 2003; Gremmo, 2009, p. 147; Davies & McKee, 2001, p. 220), which is in contrast to approved practice of language teachers positioning themselves above students as knowers and moral agents (Kubanyiaova & Crookes, 2016). The goal of the first-year training aspect of the programme is to prepare advisors to be able to support students by embracing the philosophy of ALL.

Literature Review

Advising in language learning (ALL) and reflective practice

Reflective practice is central to the advising process, thus it is logical it should form the basis of PD and training programmes for advisors. However, reflective practice has been widely alluded to in teacher education, so has become a buzzword and its meaning has become diluted. True reflective practice goes beyond merely thinking about events, but requires practitioners to question their expertise and embrace uncertainty (Cameron, 2009, p. 128). Furthermore, reflective practice does not happen in a vacuum, it requires experience and observation of practice, and a specialist body of knowledge being drawn upon (Harris, 1989, p. 16). As in the fields of counselling and ALL, reflective practice is most effective when it involves dialogue.

Advising through reflective dialogue is related to Donald Schön’s concept of reflection-on-action, and its aim is to ‘encourage a learner to look back and analyse what happened and look at it from different perspectives’ (Kato & Mynard, 2016, p.5). However, in order for advising dialogue to take place, novice learning advisors need to be trained in how to practice it because the characteristics and purposes of discourse in advising and teaching are different (Mozzon-McPherson, 2003; Inoue, 2017). As a consequence ALL draws inspiration from a variety of fields, including counselling, sports psychology, and life coaching (Kato & Mynard, 2016, p. 7). As a consequence, this literature review explores literature on professional development (PD) from multiple disciplines in a range of settings, beyond language teaching.

Professional development programmes

PD activities need to be relevant and meaningful to those who participate. As Kennedy (2016) states in a paper concerning teacher PD, participating in a programme does not necessarily equate to engagement or learning. Lutz and her colleagues found that focussing on real problems was one of the factors in a successful PD programme for medical professionals (Lutz, Sheffer, Edelhaeuser, Tauschel & Neumann, 2013), which drew upon reflective practice to develop an attitude towards practice as well as skill; Watanabe (2016, p. 103) also sees exploration of purposes as a quality of reflective PD. To evaluate a PD programme, it is necessary to focus on engagement rather than completion, on whether programme content is related to problems faced by its subjects, and whether the programme encourages reflection. Ideally a PD programme should involve training that matches what subjects immediately need to do, and input from other PD activities should be things that can be put into practice in the setting.

An analysis of professional development practice among counsellors in India found reading, practical experience, discussion of experience and life experience to be catalysts of PD (Kumaria, Bhola & Orlinsky, 2018). Related to life experience, Watanabe’s study of high school teachers in Japan suggests that a deeper understanding of oneself is necessary for professional development and that PD practices need to be holistic, rather than merely focussing on skill development (Watanabe, 2016, p. 167; 162). Investigating teacher education in the United States, Kintz and her colleagues also found critical discussions on practice among practitioners to be a key driver of departmental PD (Kintz, Lane, Gotwals & Cisterna, 2015), and among experienced ESL teachers in Canada, Farrell found that PD sessions, discussion and collaboration with peers facilitated reflection (Farrell, 2013, p. 1076). Effective PD programmes need to encourage discussion of practice within the workgroup while also attending to the individual subjects of the programme. An indication of success in this programme would be that advisors share and discuss their experiences and professional practices.

Mentoring programmes

Mentoring has been shown to aid integration into, and improve productivity and commitment towards PD programmes (Irby, Lynch, Boswell & Kappler Hewitt, 2017). In teacher education, mentoring has often been hierarchical with an experienced mentor leading a less experienced mentee, although it has been suggested that more informal approaches and using near peers may be more effective (Chitpin, 2011; Mann & Tang, 2012). To make relationships between mentors and mentees more equitable, university lecturers have developed a three-way support system (Stilwell, 2009), and library professionals have developed a non-face-to-face system to reflect and develop as a community (Goosney, Smith & Gordon, 2014). Literature from ALL practitioners supports the idea that a hierarchical relationship between mentor and mentee is unhelpful, ‘Mentoring relationships become beneficial when the imbalance of power, such as difference in age and experience between mentor and mentee, is prevented’ (Kato, 2017, p. 275). Power relations can be neutralised through narrative storytelling, which Katz (2011) argues can help build support and is effective when a mentoring programme is likely to be short; advisors at KUIS have previously shared stories through keeping a mentor-mentee journal (Lammons, 2012; Yamamoto, 2017). Mentoring can be a powerful driver of PD, but the mentoring aspect of a PD programme needs a rigid structure and relationships need to be close.

A model for effective PD?

While Bates and Morgan’s (2018) model of effective teacher professional development has influenced this paper, most notably in highlighting the importance of observation or modelling practice and workgroup collaboration, there are some problematic aspects to their framework. The section on active learning is not fully developed and the section on content focus – connecting literature to practice – could be developed to describe a more cyclical and ongoing process of synthesising theory and action, rather than being ‘homework’ to memorise content. Therefore, in the spirit of realist evaluation, a decision was taken to focus on the uniqueness of this programme rather than trying to apply general models of best practice.

Method

Project-level decisions

Advising in language learning (ALL) is based on sociocultural principles, where knowledge is viewed as a social product (Kato & Mynard, 2016, p. 1; Mynard & Carson, 2012, p. 32), therefore it was decided that an evaluative approach with the same epistemological perspective would be appropriate. Realist evaluation works from the premise that programmes are social systems, and at the centre of the system are the people in it, the context it exists in and its history (Pawson & Tilley, 1997, p. 63; 65). A realist approach to evaluating the advisors’ PD programme at KUIS fits the objectives of this research because its results are likely to be actionable; rather than attempting to generalise, the approach seeks to understand what it is about the specific participants and setting that makes the programme succeed, fail or otherwise. Realist evaluation also offers a counterpoint to using complexity theory (Astbury, 2013, p.393), which has become fashionable in language education and training for language teachers (Feryok, 2010; Zheng, 2013).

The population that this research represents are the 11 people who had worked as learning advisors at KUIS during the academic year 2017/18, the first year after the SALC moved to a new building. A sample of six people was invited to participate in this research. This sample is representative of the gender, experience and nationality balance of the population. Of the six contacted, five participated in the project; one person was unavailable to be interviewed during the data collection window.

Ethical approval was sought and gained from the relevant gatekeepers. An ethical decision was made to deidentify all participants in the research and those mentioned with a connection to KUIS using a letter code.

Design-level decisions

Beyond the population of learning advisors, other stakeholders are invested in the success of the PD programme for advisors. The initial stages of a realist evaluation are ‘organised around the development of contexts, mechanisms, outcomes (CMO) propositions’ (Pawson & Tilley, 1997, p. 182). From these theories, the evaluator can hypothesise about what makes the programme work. Having input from a stakeholder who has direct knowledge of the mechanisms of advisor PD programmes, the context, and the terms of the social relations that take place in the setting gives the researcher’s theories more weight (Pawson & Tilley, 1997, p. 70). Therefore in the first stage of data collection, Z, who had knowledge of the original advisor PD programme at KUIS in 2006, was invited to discuss CMOs of the advisor PD programme in order to develop initial theories about the programme.

Following the development of the initial programme theories, an interview guide was created to cover these theories and related subtopics (Fielding & Thomas, 2016, pp. 288-289). The guide was designed so that interviews would take around 45 minutes to complete. Interviews were scheduled between March 16 and April 3, 2018.

Interview procedure

The participants were offered the opportunity to choose the time and place of their interview. The researcher collected audio data from interviews with the five participants, and then transcribed these conversations. Transcriptions were analysed in three stages. Firstly, a priori thematic analysis was done in order to code data to the four CMO theories that had earlier been developed. Following this, each participant’s data were compared theme by theme, and a chart summarising each theme was produced. Secondly, the transcripts were reread and reanalysed to identify emerging themes and personal narratives. Data from the first two stages of analysis were then used to revise the CMO propositions about the programme to inform research questions 1 and 2. The final stage of analysis was to code the data against effective PD practices suggested in the literature in order to appraise the programme in relation to practices suggested elsewhere and thereby address research question 3.

Results

Stage 1: Stakeholder meeting to develop initial programme theories

Z was able to clarify the underlying philosophies behind the programme. Being able to construct dialogue is an essential capability for advisors to develop, and Z opined that this skill transcends the workplace and enriches all aspects of and advisor’s life.

The discussion covered basic training workshops for novice advisors, and how one-to-one talk or journaling can be used in PD to mirror practices between advisors and students. Mentoring was an area Z expressed strong feelings about, suggesting that it is essential for advisor PD and requires a pathway that supports mentees becoming mentors.

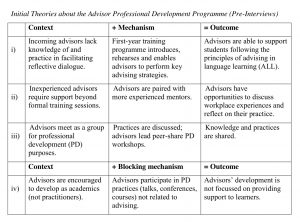

Following Z’s input the initial programme theories were developed. These four theories are presented in Table 1, in which the CMO propositions of each theory are described.

Table 1

In order to evaluate this programme, it is necessary to define what constitutes success in each for these programme theories. It was decided that the dependent variables to be assessed would be learning advisors’ perceived experiences of whether:

i) First-year training gives advisors the capability to co-construct reflective dialogue with students.

ii) Advisors experience professional growth through the mentor-mentee relationship.

iii) Advisors share knowledge and practices across the workgroup.

iv) What is learnt in PD activities can be applied to practice and thereby enhance advisors’ support of students.

These dependent variables were then tested in the second stage of the research in interviews with five people who know the programme well, four advisors who are subjects of the programme and one manager who is a stakeholder.

Stage 2: Advisors’ perspectives

One term that emerged from the interview data was ‘creativity’. It was used by J to describe a realisation that she needed to go beyond following the procedures of others to become an effective advisor, by Y to describe how original ideas and practices emerged from mentoring relationships in the programme, and by A to describe her development as a researcher and an academic. This suggests that one of the things about the people which leads to this programme being successful is taking a creative approach. Prior research states that reflection is important, but creativity is required to turn reflection into action.

Theory i): First year training supports reflective dialogue. All of the interviewees were positive about the content of the training aspect of the programme in developing skills to engage in effective dialogue with students. C and J stated that all of the sessions helped them develop. Although C and K described failure to retain some information initially, that they stated they were able to review and have further discussion with trainers and mentors suggests a strength in the programme; the availability of experienced peers helps novice advisors to get the knowledge they need. J revealed that much of her first-year training focused on written advising and indicated that this was because at that time there were a large number of students who required this service. This suggests that the programme is flexible and can focus on immediate needs of students when required.

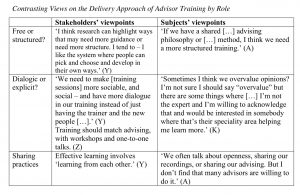

In contrast to the content of first-year training, opinions on how training is delivered differed. In particular, dissention between stakeholders and subjects of the programme emerged. Table 2 summarises how the preferences of the stakeholders for dialogic training practices to match advising with students contrasted with two of the subjects who called for a more structured and direct approach. Additionally, while A seems to agree with management’s ideals of openly sharing practices in order to learn, this policy appears to be implemented unsatisfactorily.

Table 2

As well as ‘learning from each other’, stakeholder Y describes making ‘room for discussion or reflection’ as an aspect of effective learning. In recalling an effective training session, Advisor C reports a situation in which discussion and reflection took place after he, his trainer and another advisor had read a journal article:

We just talked about […] reflecting students’ emotions. […] Listening reflectively and being a mirror for them. I don’t think we practiced much in that we just read the article and kind of discussed our reactions to it. But that reading was really good fun and interesting for thinking about how I can listen to students in sessions (C)

In describing a successful PD experience that neither matched advising nor was directive, C’s statement indicated that having varied implementation methods can enrich the training aspect of the PD programme.

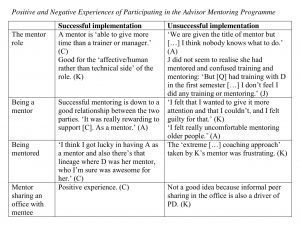

Theory ii): Mentoring leads to professional growth. Interview responses concerning mentoring received mixed responses from the four programme subjects. Two of the participants described generally successful experiences of their self-development through this aspect of the programme, but there seems to be inconsistency in the implementation of this policy, as highlighted in Table 3.

Table 3

The two advisors who spoke of generally successful experiences of mentoring described regularly scheduled meetings which were cordial. The less successful experiences of being a mentee described by J and K involved a more hierarchical relationship, with the mentor as teacher and mentee as student. Y stated that innovative practice has emerged from freedom being given to mentors and mentees to decide how to proceed. However, the manner in which the concept of mentor blurred with trainer and office mate in the account given by J suggests a need for clarification on what the role is and what is expected from the mentorship aspect of the programme.

Theory iii): Knowledge sharing in the workplace. This theory was developed to discuss formal, whole-group PD conventions. However, the focus in all of the interviews moved towards more informal practices, in particular the impact of sharing offices with other advisors. This seems to be a powerful driver of PD in this setting. For example, J related how similar relationships with previous and current office mates have led to deep discussion and reflection about work, ‘Small talk is a waste of time for her’ (J), and described how these conversations have a different quality to those she has with her husband. She puts this down to her personality: ‘I think I’m an introvert, so I think about what I do a lot’ (J), and this reflective trait may be a reason that this productive environment exists within this group of people. Y reported that in the advisor recruitment process, those who have a desire to develop themselves are more likely to be offered a job.

None of the interviewees expressed enthusiasm for doing PD as a group, but ideas on how to better use team meetings to develop discussion and community emerged. A is against having more meetings, and Y shared a vision of having whole-group PD as an add-on to the current meetings. C gave a number of suggestions on how the meetings could be used productively, including giving time to share external PD opportunities and to do some practical troubleshooting, for example to share comments written to module students, during quieter periods of the semester.

One issue with whole-group PD that emerged is that it requires the whole workgroup taking the same approach, which J is firmly against. ‘I’m… kind of… looking for something different’, and ‘I’m looking for more opportunity for professional development but in a new way’ (J), and suggested that people had previously participated in group PD merely because they felt obliged to. A personal PD approach is favoured by K and C: K’s PD choices are influenced by friends in other fields, and when asked about his plans for his second year, C stressed he needs to develop his own interests. A possible limitation of the current programme is that experienced advisors might not feel challenged by PD done in a group. Additionally, these findings suggest that resources are lacking to provide everything on site that the advisors require to develop themselves.

Theory iv): Relevance of PD activities. K implies that an advisor following their own professional development goals is setting a good example for students, who advisors encourage to work towards often ambitious language learning goals. ‘Go, live your dreams, I gave up on mine’ (K). This line was delivered in a sarcastic tone, and suggests that in a worst-case scenario, a lack of choice in PD opportunities would damage a programme’s subjects by quashing their enthusiasm and making them less appropriate role models for students.

There was, however, agreement among the participants that conferences and talks are not always relevant. C found that he does not always connect with speakers when the topic is not ‘directly applicable to what I was doing at that time’ (C). Similarly, A, J and K all expressed that some conferences that they have attended are not relevant to advising, but that, depending on the conference, there is value from a PD point of view because they can help with research. Talks can ‘give perspective’ (A), and be ‘useful analytically’ by suggesting an alternative lens through which to view a problem (K).

For Y, developing as a researcher is an important part of the role. ‘I always encourage new advisors to participate in the academic community’ (Y), and suggests that that advisors benefit from doing presentations in their first year. K argues that academic development helps advisors understand the setting better. In defence of his choice to learn a programming language, not an obvious route to support language learners, he explains how it can inform practice:

So, I’m already, with data sets we have – being able to apply this to analyse feedback that we’re getting, find connections and patterns and ways that can help us improve the SALC, or understand the context of the students’ context of the SALC and the campus environment […] Skills in “R” become a tool to, as I develop them, further understand this data we already have now. So that we can make informed decisions of it and improve. (K)

This narrative experience shows how understanding and giving appropriate support to learners is not merely a case of developing dialogic skills, or doing training in a related field such as coaching or counselling, but can be achieved in numerous creative ways.

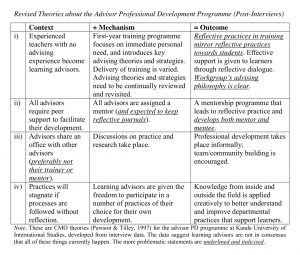

Revised programme theories

Following analysis of the interview data, the initial CMO propositions were reviewed, and the revised theories about the PD programme are shown in Table 2. Changes were made to all four theories based on the input of the five participants, most noticeably with diverse PD practices being recast in a more positive light in Theory i (towards Z’s assertion that ‘everything comes back to the students’ rather than the researcher’s fear that student needs came second to advisor desire), and the mechanism for Theory iv becoming more focussed on informal PD practices.

Table 4

While the data presented in Table 4 suggest how the programme operates, that is not to say it operates perfectly. With mentoring for example, the potential is there for reflective practice. However, further experimentation and perhaps action research is required to ensure that trust between partners is built, there are no barriers to communication, and whether tasks or personal storytelling are formally incorporated.

With first-year training, there is a greater focus in the revised theory on flexibility of the content of training based on immediate need, and on the use of different modes of delivery. Participant insight into using outside training opportunities as PD suggests that observing rather than leading training might be more conducive to reflective practice.

The potential impact of informal knowledge sharing within the workgroup is a thought-provoking finding that emerges from this research. Based on these findings, it seems pertinent in the KUIS setting to focus on enhancing opportunities rather than pushing and enforcing whole-group PD. That said, further research into why participants were reticent to do more group PD; a possible reason that comes from the data gathered is that it is time consuming and that PD is of secondary importance to satisfying student needs.

Discussion

This section examines the findings under the categories set out in the research questions, namely the implementation of the programme, the people and setting, and components required for an effective PD programme.

Implementation

One strength of the programme is that advisors are able to put the content of their training and their ideas into practice. There is a certain amount of flexibility in terms of content focused on and delivery style which relates training to real issues, (Lutz et al., 2013) and builds a connection between reading and experience (Kumaria et al., 2018). Examples of this include the description by J of training being adapted to the needs of the advisors at that time, and C’s experience of a session where the trainer and two advisors discussed literature in order to deepen understanding. These examples show the programme performing favourably in the area of content focus, one of Bates and Morgan’s (2018) seven components of good PD practice.

Another aspect of effective PD described by Bates and Morgan is feedback and reflection. Reflection is embedded both in the literature of advising in language learning (Kato & Mynard, 2015), and in the practices described by the participants in this study. However, feedback and reflection are ‘two distinct and complementary processes and are both part of effective PD’ (Bates & Morgan, 2018). Feedback is not a theme that emerged from this research and is an area that needs extra consideration as this programme develops.

Peer observations as PD have been shown to have a positive effect on student learning outcomes (Shaha, Glassett & Copas, 2015), but they have not been successfully implemented in this advisor PD programme according to A. Peer feedback can be intimidating, but research suggests that it has the capacity to strengthen professional relationships and build mutual respect (Shortland, 2010). This programme may benefit from implementing a three-way peer observation aspect in order to reduce the chance of confrontation and observees feeling threatened (see Stillwell, 2009).

The people and setting

Despite limited peer observation taking, this study suggests that one of the strengths of this programme lies in the people being willing to engage in PD and having the desire to support students. Furthermore, participants talked of good relationships within the team and a desire to learn from one another.

Regarding the setting in which this PD programme has been implemented, there are two prominent features that encourage advisors’ professional development. First, in terms of expert support from within the department, from lectures from visits to the university, and from financial support for advisors to attend academic conferences. In addition, in contrast to other settings (see Carson, 2015), advisors at KUIS are full time and do not have teaching obligations. This means their focus is on ALL and their day-to-day practices as well as their PD is on advising rather than other things. Educational institutions need to set aside both time and money for dedicated advising staff in order to maximise PD and, ultimately, offer the best support to learners.

Elements of an effective programme

Opportunities for informal discussion about practice were shown to be powerful drivers of professional development in this research. These informal reflective dialogues mean practices are dynamic rather than automatic (see Farrell, 2013, p. 1075). Findings in other studies of departmental PD practices also suggest informal peer discussion is indispensable (Kintz et al., 2015), this is a challenge to widespread belief that informal PD has a lesser status than, for example, mentoring (see OECD, 2009). The importance of informal learning should not be underestimated and educational institutions should strive to provide their staff with environments and opportunities to interact informally and trust them to use these opportunities professionally.

While processes need a review in this programme, mentoring has been shown to have a positive impact on programme subjects when implemented well. In terms of relationships in the mentoring element of programmes, findings here echoed the literature on mentoring that hierarchy in mentor-mentee relations should be minimised (Kato, 2017; Chitpin, 2011; Mann & Tang, 2012). Because creating a non-hierarchical mentoring programme where mentor and mentee feel comfortable requires finding a delicate balance, it needs to be done strategically.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This paper sets out to address the lack of research into professional development (PD) in advising for language learning (ALL) by evaluating the effectiveness of a professional development (PD) programme for learning advisors at a university self-access learning centre (SALC) in Japan. The research was undertaken by advisors being interviewed. Demand for research in this setting was due to the SALC department’s change in status within the university and its move to a new facility. Results suggest that the implementation of first-year training for advisors is successful, and part of this success is due to its blending of delivery styles and practices that encourage reflection. However, reaction to the implementation of the mentoring element was mixed, suggesting a need for clarity of purpose in policy documents and the need for a tool such as a journal to aid PD practices, as well as further research into this area of the programme.

The research method was underpinned by a realist perspective. As well as positioning the research in a different discipline to previous research in language education and teacher PD where complexity theory is popular (Astbury, 2013; Feryouk, 2010; Zheng, 2013), the realist approach meant the project could specifically focus on the PD programme’s particular mechanisms to understand its outcomes. The approach allowed for stakeholder input in the creation of the programme theories that informed the design of the research instrument, and helped to identify differences in perspective between managers and advisors, particularly regarding the delivery of training.

One of the major findings is the implication that informal discussions within the workgroup are a powerful driver of PD. Another finding is that self-exploration and choice are important drivers of professional growth (also see Watanabe, 2016). One of the strengths of the people and setting of this programme is that there appears to be both willingness from individual advisors and support from the institution for personal PD goals to be managed by the subjects. In addition, advisors being employed full time and encouraged to participate in PD activities on and off campus helps to encourage workgroup collaboration that goes beyond ‘contrived collegiality’ (Bates & Morgan, 2018). The implication is that it is fitting for other educational training and PD programmes to incorporate self-directed elements and provide staff with working conditions, such as time and financial support, which foster professional growth.

The following recommendations are proposed specifically for the advisor PD programme at KUIS but will be of interest to organisers of other advisor or teacher development programmes. Effective PD requires that:

- Training both has a clear message and encourages self-directed learning. Ongoing review of training practices is needed to ensure implementing a clear shared philosophy and advising methodology is balanced with having a dialogic dimension in training.

- Members of the workgroup share practices. Observation is one way to do this, and organising a non-hierarchical peer observation system will benefit this setting.

- People are integrated into a workgroup and their commitment is boosted by having a mentor system. However, a strategic approach to implementing mentoring is needed. A required mentor-mentee journal would encourage reflective practice and match advising procedures and allow for feedback to be built into the programme more explicitly.

- Relaxed discussion takes place among the workgroup. Maintaining a professional and friendly working environment will encourage creativity and informal development.

- PD is explicitly done to benefit students. The findings indicate that varied PD promotes learner as well as advisor development; however, this should be made explicit in policy guidelines.

Notes on the contributor

Huw Davies is a learning advisor at Kanda University of International Studies and a PhD student at Lancaster University. He holds a MEd in Applied Linguistics from the Open University. He has published papers concerning learning strategies and learner autonomy.

Acknowledgements

This research was undertaken as part of the PhD in Education and Social Justice in the Department of Educational Research at Lancaster University. I am pleased to acknowledge the contribution of tutors and peers in supporting the development of this study and its report as an assignment paper.

References

Astbury, B. (2013). Some reflections on Pawson’s Science of evaluation: A realist manifesto. Evaluation, 19(4), 383-401.

Bates, C. C., & Morgan, D. N. (2018). Seven elements of effective professional development. The Reading Teacher, 71(5), 623-626.

Cameron, M. (2009). Review essays: Donald A. Schön, the reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic books, 1983. Qualitative Social Work, 8(1), 124-129.

Carson, L. (2015). Human resources as a primary consideration for learning space creation. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 6(2), 245-253. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/jun15/carson/

Chitpin, S. (2011). Can mentoring and reflection cause change in teaching practice? A professional development journey of a Canadian teacher educator. Professional Development in Education, 37(2), 225-240.

Davies, H. (2019). Research materials: Advisor education professional development programme [Data]. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.34597.45289

Davies, V., & McKee, J. (2001). The double-decker learning bus: Teacher and adviser. In M. Mozzon-McPherson & R. Vismans, Beyond language teaching towards language advising (pp. 208-221). London, UK: Centre for Information on Language Teaching and Research.

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Research brief: Effective teacher professional development. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Effective_Teacher_Professional_Development_BRIEF.pdf

Farrell, T. C. S. (2013). Reflecting in ESL teacher expertise: A case study. System, 41, 1070-1082.

Feryok, A. (2010). Language teacher cognitions: Complex dynamic systems?. System, 38(3), 272-279.

Fielding, N., & Thomas, H. (2016). Qualitative interviewing. In N. Gilbert & P. Stoneman (Eds.), Researching social life (4th ed.) (pp. 281-300). London, UK: SAGE.

Goosney, J. L., Smith, B., & Gordon, S. (2014). Reflective peer mentoring: Evolution of a professional development program for academic libraries. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 9(1).

Gremmo, M.-J. (2009). Advising for language learning: Interactive characteristics and negotiation procedures. In F. Kjisik, P. Voller, N. Aoki & Y. Nakata (Eds.), Mapping the terrain of learner autonomy: Learning environments, learning communities and identities (pp. 145-167). Tampere, Finland: Tampere University Press.

Harris, I. B. (1989). A critique of Schön’s views on teacher education: Contributions and issues. Journal of Curriculum and Supervision, 5(1), 13-18.

Imamura, Y. (2018). Adapting and adopting new language policies in a self-access centre in Japan. Relay Journal, 1(1), 197-208. Retrieved from https://kuis.kandagaigo.ac.jp/relayjournal/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Imamura-Relay-Journal-197-208.pdf

Inoue, S. (2017). Professional development for language learning advisors. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(3), 268-273. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep2017/inoue/

Irby, B. J., Lynch, J., Boswell, J., & Kappler Hewitt, K. (2017). Editorial: Mentoring as professional development. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 25(1), 1-4.

Kato, S. (2017). Effects of drawing and sharing a ‘picture of life’ in the first session of a mentoring program for experienced learning advisors. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(3), 274-290. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep2017/kato/

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

Katz, H. N. (2011). Stories and students: Mentoring professional development. Journal of Legal Education, 60(4), 675-686.

Kennedy, M. M. (2016). How does professional development improve teaching?. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 945-980.

Kintz, T., Lane, J. Gotwals, A., & Cisterna, D. (2015). Professional development at the local level: Necessary and sufficient conditions for critical colleagueship. Teaching and Teacher Education, 51(3), 121-126.

Kubanyiova, M., & Crookes, G. (2016). Re-envisioning the roles, tasks and contributions of language teachers in the multilingual era of language education, research and practice. The Modern Language Journal, 100, 117-132.

Kumaria, S., Bhola, P., & Orlinsky, D. E. (2018). Influences that count: Professional development of psychotherapists and counsellors in India. Asia Pacific Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 9(1), 86-106.

Lammons, E. (2012). Pathfinder: Transitioning from teaching to advising. Independence: The IATEFL Learner Autonomy SIG Newsletter, 55, 32-34.

Lutz, G., Scheffer, C., Edelhaeuser, F., Tauschel, D., & Neumann, M. (2013). A reflective practice intervention for professional development, reduced stress and improved patient care – A qualitative developmental evaluation. Patient Education and Counseling, 92, 337-345.

Mann, S., & Tang, E. H. H. (2012). The role of mentoring in supporting novice English language teachers in Hong Kong. TESOL Quarterly, 46(3), 472-495.

Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2003, April). Language learning advising and advisers: Establishing the profile of an emerging profession. Actes de la IX trobana de centres d’autoaprenentatge. Bellaterra, Spain: Generalitat de Catalunya.

Mynard, J., & Carson, L. (2012). Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

OECD. (2009). Creating effective teaching and learning environments: First results from TALIS (Teaching and Learning International Survey). Paris, France: OECD Publications. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/education/school/43023606.pdf

Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic evaluation. London, UK: SAGE.

SALC. (2017). SALC handbook 2017-2018. Chiba, Japan: Self-Access Learning Centre.

Shaha, S. H., Glassett, K. F., & Copas, A. (2015). The impact of teacher observations with coordinated professional development on student performance: A 27-state program evaluation. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 12(1), 55-64.

Shelley, M., Murphy, L., & White, C. J. (2013). Language teacher development in a narrative frame: The transition from classroom to distance and blended settings. System, 41(3), 560-574.

Shortland, S. (2010). Feedback within peer observation: Continuing professional development and unexpected consequences. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 47(3), 295-304.

Stilwell, C. (2009). The collaborative development of teacher training skills. ELT Journal, 63(4), 353-362.

Trowler, P., Fangharel, J., & Wareham, T. (2005). Freeing the chi of change: The higher education academy and enhancing teaching and learning in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 30(4), 427-444.

Watanabe, A. (2016). Reflective practice as professional development: Experience of teachers of English in Japan. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Yamamoto, K. (2017). The journey of ‘becoming’ a learning advisor: Reflection on my first-year experience. Relay Journal, 1(1), 108-112. Retrieved from https://kuis.kandagaigo.ac.jp/relayjournal/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Yamamoto-Relay-Journal-108-112.pdf

Yoshikawa, H., Leyva, D., Snow, C. E., Treviño, E., Barata, M. C., Weiland, C., Gomez, C. J., Moreno, L., Rolla, A., D’Sa, N., & Arbour, M. C. (2015). Experimental impacts of a teacher development program in Chile on preschool classroom quality and child outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 51(3), 309-322.

Zheng, H. (2013). Teachers’ beliefs and practices: A dynamic and complex relationship. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 41(3), 331-343.

First of all, I’d like to thank you for sharing your work. I am particularly and personally interested in this topic because I am in charge of making decisions that directly impact the professional development and training of the advisors in our self-access center and I have also done research on it for our specific context.

It is always interesting to learn about other projects and your paper draws a very clear and honest picture of your programme. This is very helpful to all of us who are on the same search for a better understanding of our job of supporting students.

I know firsthand how difficult it is to try to get a research project that is meant for a doctoral thesis to fit into an assignment paper, congratulations on managing that. I enjoyed the breakdown of the points you explore in your research, it allowed me to visualize a more complete image of the total programme and the full scope of your research.

The workgroup and mentoring you discuss immediately made me think of something we have been focusing on in our PD project, and I wonder if it might be useful for the situations you are describing and reporting about your context to consider the possibility of looking into the notion of communities of practice. Some recommendations I can give you to read around this topic are:

Hara, N. (2009). Communities of Practice: Fostering Peer-to-Peer Learning and Informal Knowledge Sharing in the Work Place. Berlin: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice. Learning, Meaning and Identity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E. (2010). Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems: the career of a concept. In C. Blackmore (Ed.), Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice (pp. 179 – 198). London: The Open University – Springer.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. (2002). Cultivating Communities of Practice. A guide to managing knowledge. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Again, thank you for sharing this work with us. I would love to know how your research impacts the future decisions for your center’s PD projects. Hopefully reporting on that is in your plans for later.

Dear Adelina,

Thank you very much for your supportive comment. For me, it’s a great relief that there are people who are interested in what I was researching. I hope that we will be able to apply my findings to our PD programme as it evolves too. Certainly in terms of mentoring this has already started to happen, but I have concerns regarding sharing practices, and hope to have the time to push for some changes in that area.

Certainly, CoP would be an appropriate framework to use in this setting even though I decided not to for this assignment/paper. One of the reasons I didn’t is I felt that CoP retains a sense of an outsider or peripheral figure being drawn into the centre where there are powerful knowers or insiders. My sense of our department (and even our field) is that newcomers and novices are able to change the shape of the community or move the centre, and that it is democratic. (I believe Wenger has addressed this issue in his more recent work and I probably need to reconnect with CoP at some point).

I’d be interested in hearing more about your PD projects too.

Thanks again.