Enríquez, Larisa. Universitat Oberta de Catalunya

García, Iolanda. Universitat Oberta de Catalunya

Enríquez, L., & García, I. (2019). Formative assessment for autonomous learning through argumentation: A proposal within the use of the online Dialogue Design System. Relay Journal, 2(2), 437-449. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020217

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

There has been a concern to help students learn how to argue in order to become better learners. Different argumentation models have been used as a teaching strategy. In 2009, Makino designed the Dialogue Design System (DDS) which is based on Toulmin’s argumentation model (2003). Through the iterative use of a didactic resource called “idea cards”, the active participation of the student is stimulated as well as the development of critical analysis and the construction of reasonable and well-founded arguments are also enhanced. DDS has also been avowed as an adequate strategy to strengthen, not only argumentative skills, but also skills related to autonomous learning.

This work is part of a doctoral research project that considers the design and development of an online tool based on the DDS model. For the specific case of the assessment of written argumentative and autonomy skills, a descriptive and analytical study will be conducted. For this purpose, two assessment tools are proposed: one based on Deane and Song’s learning progression model (2012) and the second developed under the influence of Tassinari’s dynamic model for autonomous learning (2010). The following paper presents the foundations and design of the Self-Assessment of Progress in Argumentative Autonomy instrument (SAPAA).

Keywords: Autonomous learning; argumentative skills; dialogue design system

Autonomy in the learning process entails the design of strategies, methods and tools that allow the student to achieve self-regulation, as well as self-determination. However, for apprentices to become autonomous, it is necessary that they develop certain skills such as defining their own learning objectives, selecting learning strategies, and monitoring their learning process, among others. There are different authors that link argumentative skills with the ability of autonomous learning. In 2009, Schwarz analysed argumentation as a process to learn. A case study that the author reviewed was that of Cobb, who uses argumentation as a strategy for teaching mathematics, noting “curiously and almost paradoxically, the concern of being understandable to others and being accepted by them leads to autonomy in active participants “(as cited in Schwarz, 2009, p. 45). In another context, Budán and Simari (2013) indicate that to help students become more autonomous in their learning process and develop internal cognitive abilities such as critical thinking, it is very helpful to use argumentation schemes. Also, Andrews stresses that “being rational means being able to learn from mistakes, criticizing semi-framed hypotheses and the failure of interventions in experimental and non-experimental situations”. These are all metacognitive skills linked to self-assessment exercises (Andrews, 2010, p. 18).

Schwarz (2016) states that some of the argumentation models used as a teaching strategy are those proposed by Toulmin (2003), Perelman (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1958) or Plantin (1998). In specific the Dialogue Design System (DDS), developed by Makino (2009), is a teaching model that has been used with higher education students to enhance active participation, academic dialogue, informal logic and autonomous learning. The DDS is based on Toulmin’s argumentation model and is part of a broader model for the construction of knowledge, the Message Cross Construction (MCC), that combines formal and non-formal logical argumentation. Through the DDS, its author, Makino sought to promote among her students, active participation through provocation, questioning, critical analysis and the construction of reasonable and well-founded arguments under the non-formal logical perspective. To achieve this goal, Makino introduced a didactic resource called “idea card”, which is the object on which the argumentative work of the student focuses, individually and in a written way (Makino & Lepissari, 2014).

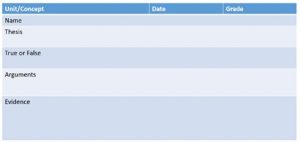

The idea card is a didactic device that takes the form of a table, which invites students to work around a thesis designed by the teacher. The student has to construct an argument to defend the main statement (or refute it), showing not only reasons but also documented evidence supporting them. Figure 1 illustrates the idea card that students have to fill in.

Figure 1. Idea card.

It is important to notice that idea cards are evaluated from the point of view of the argumentative quality that the student develops, instead of evaluating whether the answer is correct or incorrect. In this way, it is sought that students deepen in the study of the subject to sustain the position they assume towards the assertion that is raised by the professor. In addition, after all idea cards are evaluated, different positions should be confronted with the contrary arguments that some peers might have pointed out. This should create a space for analysis and discussion that invites to self-reflection and self-evaluation. This iterative exercise helps, in a transversal way, to form a study habit where reflection, questioning, research, documentation, and comparison of data are constantly in action. In this way we can notice that, although the model works directly with skills for argument construction, it indirectly supports the development of other skills, such as organization in the study, documentary research and critical thinking which are skills also related with learner autonomy.

Purpose and methodology

The general research proposal considers the design and development of an online tool based on the DDS model and, from its implementation, it evaluates the development of argumentative skills that could also be associated with the increase of the capacity for autonomous learning. A Design Based Research approach is being used to design, develop and evaluate the proposed tool. During the implementation phase for the specific case of the assessment of written argumentative and autonomy skills, a descriptive and analytical study will be conducted. For this purpose, two assessment tools are proposed. The first one is based on Deane and Song’s “learning progression for argumentation model” (2014) in order to assess the strengthening and development of argumentative skills that students put into play when solving the idea cards and the second is developed under the influence of Tassinari’s “dynamic model for autonomous learning” (2012), but in the context of self-assessment of argumentation skills.

Learning progression for argumentation: Dean and Song’s model

The CBAL (Cognitively Based Assessment of, for, and as Learning) research initiative [1] emphasizes the idea that learning progressions are qualitative changes in students’ performance that indicate when they are ready to move on to more challenging tasks within a general skill. The formal definition that refers to a progression of learning is a description of “qualitative change at the student level of sophistication for a key concept, process, strategy, practice or habit of the mind” (Deane & Song, 2014, p.102).

Taking this into account, Deane and Song (2012) developed the “learning progression for argumentation”, which considers different forms of expression, under a model of competencies involved. In particular, the authors refer to an argumentation cycle with five main phases in which a skilled person participates in order to build an argumentation. The five phases and the general skills associated to each one of them, are as follows:

- Phase 1. Considers a position à Assumes a position

- Phase 2. Organizes and presents arguments à Frames a case

- Phase 3. Understands the stakes à Appeals building

- Phase 4. Explores the concept à Investigates and consults

- Phase 5. Creates and evaluates arguments à Provides reasons and evidences

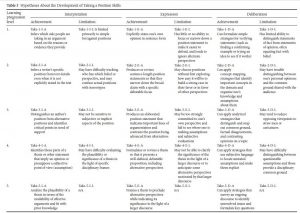

For the learning progression of argumentation, phases 2 and 3 can be merged. Each of the general skills associated with the phases are broken down into three cognitive processes that, in turn, integrate five different maturity levels that take place when assessing the progression of students in these different phases. The three progress variables are: reading (interpretation), writing (expressive) and critical thinking (deliberative) and the five maturity levels are: elementary, fundamental, basic, intermediate and advanced. The authors present in the model specific skills that are achieved at each maturity level, for each progress variable, in every phase, as well as the possible limitations that might be happening in it (Table 1 is an extract of the model for phase 1).

Table 1. Hypothesis about the development of taking a position; table caption presented by Deane and Song, 2015, p.13. (Copyright 2015 by John Wiley and Sons. Reprinted with permission.)

To assess objectively the relationship between the progression of argumentative skills and the strengthening of some autonomous learning skills, we consider the possibility of linking Deane and Song’s learning progression (2015) with four autonomous learning components mentioned in Tassinari’s dynamic model for the evaluation of autonomous learning (2012).

Tassinari’s dynamic model for autonomous learning

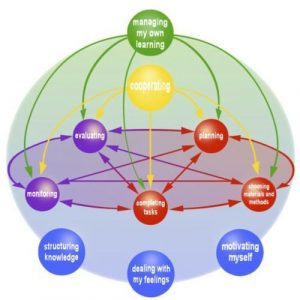

Tassinari’s model identifies five dimensions for autonomous learning: one of them is predominantly action-oriented, another is cognitive oriented, while a third is focused on metacognition. It also identifies a predominantly affective and motivational dimension and a social dimension. For each of the dimensions, the author links a set of components, which refer to areas of competence, skills and actions. They are expressed through verbs to focus on their action-oriented character and process: “structuring knowledge”, “dealing with my feelings”, “motivating me”, “planning”, “choosing materials and methods”, “completing tasks”, “monitoring”, “evaluating”, “cooperating”, and “managing my own learning” (Tassinari, 2012, pp. 28-29). The model is presented in Figure 2. Each color represents a dimension and the coloured spheres are the components related to that dimension. As is visible below, there are components that relate to more than two dimensions, depending on the perspective from which that component is analysed, whether in an emotional, cognitive, metacognitive, social and/or active dimension. For instance, the monitoring component considers descriptors from the metacognitive dimension (I can reflect on my learning) as well as from the emotional dimension (I can recognise what prevents me from completing a task).

Figure 2. Dynamic model of autonomous learning. Taken from Tassinari (2012, p. 30).

Likewise, the components integrate descriptors (or statements) specific to skills, competences and learning attitudes that the student uses when faced with the situation of learning. In the case of Tassinari (ibid.) it refers to the action of learning a new language. The author explains that the descriptors are divided into two types: macro-descriptors and micro-descriptors. Macro-descriptors are general statements that serve for an initial orientation of the students in the self-assessment exercise, while micro-descriptors are more detailed statements, through which the student can differentiate their skills, behaviour and attitudes to evaluate their learning more accurately. The descriptors proposed by Tassinari are formulated in terms of “I can do it”, considering that it is the student who answers the assessment tool that contains the descriptors to encourage internal and personal reflection on the learning process.

A proposal for evaluating autonomous learning through argumentation skills

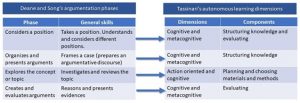

As it has been mentioned, Tassinari’s model was designed “to develop a description of learners’ competencies and skills as a tool for supporting autonomous processes in learning and teaching foreign languages in higher education contexts” (2012, p. 25). Although it is not exactly the context we are dealing with, since we are working with processes in learning argumentation, we hold that it is possible to connect both models as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Relationship between the argumentation phases of Deane and Song (2015) with Tassinari’s (2012) autonomous learning dimensions and components.

With this consideration in mind, a new assessment instrument has been designed to evaluate the progress that students believe they have achieved in argumentation. Following, we present the main characteristics of this self-assessment instrument:

- The instrument considers Tassinari’s (2012) assessment tool structure. It maintains the action-oriented approach and the idea of being a self-assessment instrument for students to use. Macro-descriptors indicate the specific argumentation phase to guide the student, while micro-descriptors describe specific skills, behaviours and attitudes that help students to evaluate their argumentation process more accurately.

- The instrument responses are Likert type response scale descriptors, in terms of “I do”. We choose the form “I do” instead of the “I can do it” one, with the purpose of obtaining more certain answers from the students, that is whether they have actually done it and not if they think they can do it.

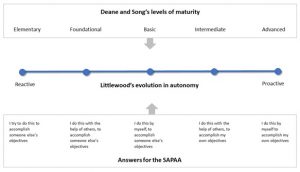

- The instrument considers five different types of answers for each micro-descriptor, referring to the level of proactivity that the student has. Littlewood (1999) states that there is a transition or evolution in autonomy, from reactive to proactive, that allows to distinguish between the control of the learning process and the entire self-determination of the person. This transition has as a final step called proactive autonomy, which refers to the stage in which a person establishes his/her own learning objectives, his/her own way of learning and the actions that give way to that learning. This is, in contrast with the reactive autonomy that describes the person who has the determination to acquire the necessary resources to achieve the objectives proposed by others (Littlewood, 1999, p. 75). The correspondence between argumentative progression and autonomous learning is illustrated below, in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Correspondence between argumentation cognitive progression and the evolution of autonomous learning.

- The instrument uses Deane and Song’s phases (2014) as macro-descriptors. The four phases involved in argument building that Deane and Song mention (merging phase 2 and 3) can also be seen as general actions that students must take. In this sense, they are the general statements that Tassinari (2012) refers to as macro-descriptors.

- The instrument uses most of the skills described in the highest maturity levels that Deane and Song (2015) highlight for the different variables of progress, as micro-descriptors (in other words, these micro-descriptors represent the desirable skills to acquire for the different phases involved in argumentation).

Self-Assessment of Progress in Argumentative Autonomy

With the aforementioned considerations, the instrument that students must respond to reflect on their own attitude and position before the process of developing the argumentative skills raised from the model of Deane and Song (2014), is shown in Appendix A.

The instrument considers five possible answers for each micro-descriptor within a range that goes from an intention to accomplish someone else’s objectives, to the capacity of executing by themselves the actions involved in accomplishing their own argumentation objectives.

There are four macro-descriptors and sixteen micro-descriptors, all of which are related to Deane and Song’s “learning progression for argumentation” (2015).

The Self-Assessment of Progress in Argumentative Autonomy instrument (SAPAA) must still be validated. However, we believe that it presents not only a specific interpretation of Tassinari’s dynamic model (2012) but also an explorative proposal to link autonomous learning assessment across different disciplines and competences. Particularly, within the online DDS model, this autonomous learning self-assessment instrument is part of a broader evaluation model that will try to assess different aspects throughout the implementation of the DDS. On the one hand, the strengthening and development of argumentative skills that students put into play will be evaluated each time a student solves an idea card, using Deane and Song’s learning progression for argumentation model. Since this task is repeated several times within a semester, it will be possible to evaluate students’ progress.

On the other side, the SAPAA instrument will be answered by students in three different periods and will help us identify if students are aware of their own progress as well as to evaluate if their self-assessment matches the reality.

In this sense, the learning progression for argumentation will allow us not only to see in detail the development of concrete argumentative skills by students, but also to visualize the way in which students progress in a general way in their own autonomy from a reactive towards a proactive one. Students who are on the lower level of autonomy development are students who, at best, exercise skills, attitudes and competencies that respond to the school environment or to the activities and tasks suggested by a third person; in other words, they are students with reactive autonomy. Furthermore, the upper level corresponds to the skills that students demonstrate in the learning process and that respond to the initiatives and goals that they impose on themselves. In this case, we would say that these are skills that a student whose autonomy is proactive, possesses.

At last, when comparing the results obtained in the learning progression for argumentation with those from the SAPAA instrument, we will be able to confirm (or not) if the relation between Deane and Song’s argumentative skills (2015) with Tassinari’s autonomous learning dimensions (2012) are correct or, if there are skills related to the social, emotional and cooperative dimensions, that are also taking place and being enhanced.

Conclusions

As it has been said, autonomous learning is a capacity that involves different skills and competences that are interrelated. It is feasible to think that, depending on a certain teaching strategy that is used, several learning abilities are being enhanced. We believe that by using the DDS model, different argumentative written skills can be strengthened and, that at the same time, it can also have a positive impact on the reinforcement of determined autonomous learning skills, mostly related to the cognitive and metacognitive dimensions in Tassinari ‘s model (2012).

Besides its evaluative purpose, it is also important to highlight the formative dimension of the instrument. By self-assessing their own progress in the argumentative exercise, students perform a process of reflection and awareness that can directly influence not only his progression in the argumentation skills but also the actual development of his autonomous learning skills.

The validation of the SAPAA instrument, as well as its implementation and evaluation with students is still pending.

Notes on the contributors

Larisa Enríquez is a PhD student in e-learning from the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC) and a full-time researcher at the CUAED (Coordination of the University of Open and Distance Education) of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). Her research interests are in autonomous learning, open and distance education and flexible models for education. She founded the autonomous learning lab at CUAED.

Iolanda Garcia is associate professor in the Department of Psychology and Education Sciences at the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC). She holds a PhD in Pedagogy and a Degree in Philosophy and Education Sciences from the University of Barcelona in Spain. Currently, she coordinates research projects focused on the design and codesign of learning environments and processes from the learner perspective: design-based research of student-centred learning models and scenarios, considering learner participation in the design of one’s own learning as well as learning regulation processes.

Acknowledgements

The “DDS en línea” is a research project funded by UNAM-DGAPA-PAPIIT program, with registration number IT400518. We would like to thank DGAPA for the support.

References

Andrews, R. (2010). Argumentation in higher education: Improving practice through theory and research. London, UK: Routledge.

Budán, P., & Simari, G. (2013). El uso del pensamiento crítico y la argumentación como enfoque para el aprendizaje autónomo en carreras de Informática. In VIII Congreso de Tecnología en Educación y Educación en Tecnología (p. 8). Buenos Aires. Retrieved from http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/27584

Deane, P., & Song, Y. (2014). A case study in principled assessment design: Designing assessments to measure and support the development of argumentative reading and writing skills. Psicología Educativa, 20(2), 99-108. doi: 10.1016/j.pse.2014.10.001

Deane, P., & Song, Y. (2015). The key practice, discuss and debate ideas: Conceptual framework, literature review, and provisional learning progressions for argumentation (Research Report No. RR-15-33). Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service. doi:10.1002/ets2.12079

Littlewood, W. (1999). Defining and developing autonomy in East Asian contexts. Applied Linguistics, 20(1), 71-94. doi:10.1093/applin/20.1.71

Perelman, C., & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1958). Traité de l’argumentation : la nouvelle rhétorique. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Plantin, C., (1998). La argumentación, Barcelona, Editorial Ariel, S.A

Schwarz B.B. (2009) Argumentation and Learning. In: N. Muller Mirza, & A.-N. Perret-Clermont (Eds.), Argumentation and Education. Boston, MA: Springer.

Makino, Y. (2009). Logical-narrative thinking revealed. The International Journal of Learning: Annual Review, 16(2), 143-154.

Makino, Y., & Lepissari, I. (2014). Dialogue Design System in a mass lecture class: Bridging the cultural gaps in pedagogy through operation videos. Proceedings of World Conference on Educational Media and Technology 2014 (pp. 1361-1370). Tampere: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Tassinari, M. G. (2012). Evaluating learner autonomy: A dynamic model with descriptors. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(1), 24-40. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/march12/tassinari/

Toulmin, S. (2003). The uses of argument. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511840005.004

[1] Research initiative of the educational measurement organization, ETS (Evaluation Teaching Standards) from USA (https://www.ets.org/cbal).

Your design is innovative in that you try to apply many frameworks to assess skills of autonomous learners in the context of argumentation cognitive progression. In a specific learning context, it helps the students to self-regulate their learning meaningfully. I am interested in how you apply the existing tools to fit your study. Unfortunately, the table which presents the model proposed by Deane and Song is not clear so it is difficult to see if the descriptors are applicable or not.

From my experience, helping the students to self-regulate their learning took time and the task has to be designed carefully. I hope the idea card is helpful. I have some suggestions to the study in that because you use participants’ self- evaluation of their argumentative skills and reflections on their performances, the keywords which would be used to see the skills of autonomous learners may not be as many as those found in the journals as in Tassinari’s study. Also in Tassinari’s study, the context is broader so there was more to say in the journal. Guided questions may be useful to help the participants reflect more so you will have enough evidence to see the development of skills of autonomous learners. Peer evaluation would be helpful to help the participants have more insights into their use of argumentative skills.

Argumentative skills are linked with critical thinking and analytical thinking. Training learners to develop argumentative skills is helpful not just to develop skills of autonomous learners but also to develop those two skills. I look forward to reading the report of your study and hope your study goes well.

Hello Pornapit,

Thank you for your comments on our work; we really appreciate it and find it meaningful. The tools described in the paper will be used as followed:

– The Dean and Song assessment tool will be used everytime a student solves an Idea card. That way we can identify individual argumentative skills progression. That tool will be used by me, with the help of the teacher.

– The SAPAA tool will be answered by students in order to invite them to self-assess their own work and to aknowledge their learning progression in argumentation. This assessment will happen three times during the semester (at the beginning, in the middle of and, at the end).

We agree with you that helping students learn and develop autonomous learning skills takes time; in that sense Idea cards are very helpfull when used periodically because they give the oportunity, not only to improve written argumentation, but also to establish studying habits. In a previous experience using Idea cards, we asked students to answer a questionanaire that included some questions on autonomous learning skills, As you mention, we sholudn´t leave that questionnaire aside and include it at the end of the semester.Thank you for the suggestion; we will be happy in sharing with you our results.