Amelia Yarwood, Kanda University of International Studies

Momoyo Asaizumi, Kanda University of International Studies

Mina Kawauchi, Kanda University of International Studies

Yarwood, A., Asaizumi, M., & Kawauchi, M. (2021). Introduction to advising for university students: Providing the tools to Self-Advise and prompt reflection in others. Relay Journal, 4(2), 78-98. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/040204

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

This article is a reflection on a course designed to introduce general advising skills and approaches to a mixed-year EFL class at a foreign language university in Japan. The authors of the article provide commentary on not only the course design but also how the course was perceived from both teacher and learner perspectives. This course was comprised of thirty 90-minute lessons covering three core topics which included (1) understanding what advising is in everyday contexts and the role of advisors, (2) using advising strategies and (3) understanding affect and how to deal with it during advising sessions. To ensure students had ample opportunities to practice the skills and strategies they had learned about, mock-advising sessions took place. Several benefits of these sessions from both the teacher’s and students’ perspectives are provided. Following a discussion of the issues encountered, suggestions for modifications are made. Additionally, an outline of how students were supported in developing their ability to analyse advising sessions for their own benefit is provided. The article concludes with a final reflection on the course as a whole from both teaching and learning perspectives.

Keywords: advising, curriculum design, advisor training, L2 advising

In the spring semester of 2021, 27 third- and fourth-year students at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) took part in a 15-week elective ‘Introduction to Advising’ course comprised of thirty 90-minute lessons. All students belonged to the English department and had obtained TOEFL iTP scores greater than 480 (CEFR B1 and above). This paper is a reflective summary of the course with the intention to inspire other educators to explore ways of making advising practices accessible to learners in the foreign language classroom.

The decision to write this reflection with my students was born from my belief that curriculum should be considered with the needs of the students at its core. While formative and summative course surveys are valuable, inviting students to participate in lengthier discussions about specific activities or design choices lends greater weight to the integral nature of student voices. To that end, a call for contributors was made after the course concluded. Two students, Mina Kawauchi and Momoyo Asaizumi, took up this opportunity, and it is their voices that have been included in this reflection.

What is Advising?

Advising in this course was situated within a sociocultural framework. Within this framework, individuals learn about the world around them through their interactions with others (Lantolf, 2000). Unlike more conventional interpretations of advising in which an expert dispenses knowledge, individuals in our view of advising are treated as experts in their own lived experiences. The role of the advisor is therefore a facilitating one in which the aim is to intentionally prompt deeper reflections and new understandings through the use of questions, metaphors and other advising strategies (Kato & Mynard, 2016). Although much of the content and tools taught in this course have origins in language learning environments, the fundamental skills are applicable to all contexts.

Why Advising?

At KUIS, advising services are available to all students during the academic year, regardless of major. The aim of this service is to encourage learners, through the use of Intentional Reflective Dialogue (IRD) (Kato, 2012), to develop their ability to self-advise. In other words, it is the role of the advisor to intentionally structure the dialogue that takes place in an advising session in order to encourage deeper levels of self-reflection. As advisees, those who use the advising services, become familiar with the processes involved, they undergo a transformation, the result of which is the ability to self-advise.

Amelia’s reasons for designing the course

Advising approaches have helped me in both my private and professional life. I felt there was an educational benefit in providing KUIS students with more explicit instruction on advising skills and strategies. I wanted them to learn and grow through reflective dialogues with not only themselves, but with others too.

The benefits of learning how to reflect, and by extension, self-advise, are significant. Individuals who are capable of self-advising possess the self-awareness to make choices that are aligned with their core values and beliefs. The outcome of such self-awareness is optimal learning and wellbeing (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Learning to self-advise may not only benefit their language learning but also their private and professional lives, which are filled with a multitude of challenges. In dealing with these challenges, an approach that prioritises the purposeful breaking down of issues may be useful. Even after graduating, there are some students who have contacted me and several of my colleagues to request advising sessions. This speaks volumes about not only the rapport built between advisor and advisee, but the necessity of opportunities for intentional reflection. In an era where lifelong learning is encouraged (Ryan & Deci, 2017; Ryan & Dörnyei, 2013), self-advising skills need to be cultivated for the simple reason that an advisor is not always available to support individuals; individuals have to learn to support themselves.

In addition to self-advising, the ability to advise others is invaluable. Not only can it make for stronger relationships, but in Japan, where senpai–kohai culture (hierarchal senior–junior relationships) is the norm in most workplaces, sporting clubs and interest groups, the ability to advise others could have both professional and personal benefits. For example, by learning to listen attentively to others and collaboratively construct narratives to understand core issues, individuals may be perceived by others as considerate, trustworthy and dependable. Professionally, this may translate into greater leadership opportunities being offered, while personal benefits may include a stronger sense of self-confidence and social competence.

Mina’s reasons for taking the course

What made me take this course was my experience as a tutor for five preparatory students (senior high school students with guaranteed university entry) in KUIS’s Global Liberal Arts department. Each tutee was dealing with a different situation (For example, some were living near the university with family, while others were moving closer to the university and living alone for the first time.), and so it was quite difficult for me to grasp their experiences and needs. Also, I assumed that each student might have been feeling anxious or worried somehow because the tutoring was carried out before the entrance ceremony, and at that time they were still attending high school. After I started being a tutor, I was able to ask questions to the organiser. It was the first time for me to be a tutor, and I didn’t have any tips or strategies but did attend a sharing session. Sometimes I wanted the chance to speak with other tutors to talk about solutions to problems by ourselves. For example, I was not sure whether I was able to comment on the tutees’ work properly to keep them motivated and help them feel like they were already a part of KUIS. I wanted to make a comfortable space for my tutees. So, I wanted to pay attention to how I commented, because when my teachers didn’t give me enough comments, I felt that my work wasn’t good enough and that I should have spent more energy on it. I wanted to prevent miscommunication, and I preferred to show that their work was good and to accept what they did. Thanks to this opportunity as a tutor, I came to realise that I have a huge interest in supporting people, especially in reducing any overwhelming negative feelings. Therefore, there were two crucial things in choosing this class: (a) to make sure what I did during tutoring was helpful and (b) to acquire technical knowledge to increase my ability to boost people’s confidence and positive emotions. As a tutor I had five tutees, and they had a variety of attitudes. If I had had advising training, I would have learned that there are four communication styles, and then it would have been easier to communicate with my tutee. Everyone has a different communication style, so when I talk to them, I could change my style of speaking based on their style. Also, some tutees were very busy while others weren’t. The tutees who had free time sometimes asked me for help. I did some personal advising with them, but at the time I used my personal intuition. If I had had some advising training during the tutor training, then I would have had more confidence and been able to practice my own personal style.

Course Design

Theory

While advising practices may be influenced by any of the many theories an individual practitioner prescribes to, my personal approach is primarily influenced by sociocultural theory and self-determination theory (SDT). These two theories therefore formed the underlying framework for advising in this course.

Sociocultural theory. At the core of sociocultural theory lies the belief that our interactions with others inform our own thoughts and actions (Lantolf, 2000; Lantolf & Pavlenko, 2001). In this way, learning is co-constructed. I believe that developing as an advisor requires an individual to consider their own experiences as well as others’ perspectives on those experiences. This collection of experiences and interpretations then becomes the foundation for how the advisor understands themselves and influences their interactions with future advisees. In a similar vein, when an advisee engages with advisors, their perspectives on the struggles they face are modified through the dialogue they co-construct with their advisor. I deemed understanding this dialogic interplay necessary for my students to learn from the beginning of the course. Without a basic understanding of sociocultural theory, I felt that my students might place too much emphasis on giving their own opinions rather than starting an advising session with a reciprocal relationship in mind.

Self-determination theory. Over the past few decades, SDT (Deci & Ryan, 1987; Ryan & Deci, 2017) has influenced practitioners’ educational philosophies by highlighting the benefits of developing courses with learner well-being and self-awareness in mind. For advisors at KUIS, the theory has been discussed since early 2018 due to the centrality of autonomy, relatedness and competence—factors which influence our learners on a daily basis (For an overview of SDT in advising, see Shelton-Strong, 2020). In order not to overburden the students with complex theory, select components of SDT were included in the course—namely, the motivational continuum (Figure 1) and the general principles of self-awareness and autonomy from an SDT perspective. The inclusion of the motivational continuum (a continuum from controlled to autonomous motivation) aligned well with in-class conversations regarding directive (telling individuals what actions to take) and non-directive approaches (supporting individuals in making their own choices), while also encouraging advising sessions to conclude in self-endorsed actions.

Figure 1

Screenshot of the Motivational Continuum as Introduced in the Course

Finally, due to the dialogic nature and themes of the course, there were ample opportunities for new perspectives and greater self-awareness to be cultivated. In particular, I had hoped that this would mean that my students could see how self-endorsed decision-making from an SDT perspective occurs in practice. Ideally, the interactive approach would lead them to appreciate the power of individual voice and autonomy in advising over more passive or controlled forms of advising.

Course content

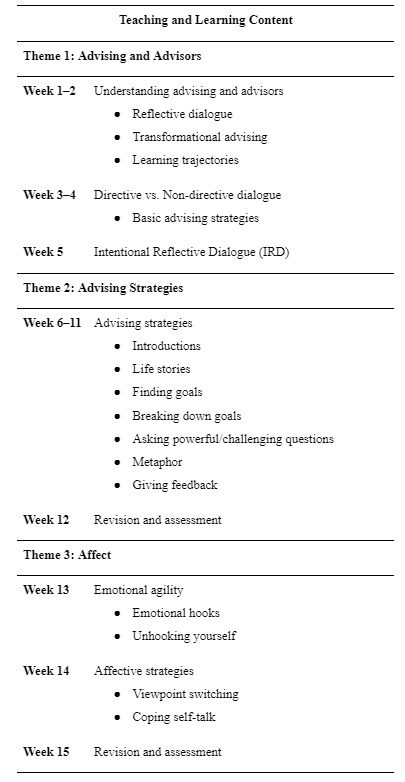

Due to curriculum requirements, the course was taught in English with some Japanese support. The content itself was broken into three general themes: (1) understanding the role of advisors and what advising is, (2) using general advising strategies (see Appendix) and (3) understanding affect and how to deal with it during advising sessions. Sociocultural theory underpinned most of the practical dialogic activities in that they focused on the co-construction of knowledge, perspectives and solutions. Meanwhile, SDT perspectives were explicitly taught in multiple lessons and frequently alluded to following the introduction of goal-setting strategies in Week 7. Interspersed between the core components of the course were lessons dedicated to revision and assessment. A more detailed breakdown of the course content can be found in Table 1.

Table 1

Overview of the Course Content

The first two of these themes were heavily influenced by my own training as a learning advisor, meaning Reflective Dialogue: Advising in Language Learning (Kato & Mynard, 2016) was used as the core text. Using the skills and strategies found in this text, the students were given opportunities to self-advise through individual activities and advise their peers during the mock-advising sessions that took place during Week 6–11 and Week 14. The final theme combined the concept of emotional agility (David, 2016) with affective strategies found in Reflective Dialogue and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) practices. Suggested techniques for enhancing emotional agility shares some similarities with CBT in that its aims are to differentiate a person’s thoughts into clear, identifiable statements. In CBT, individuals identify their core beliefs, negative assumptions and negative automatic thoughts (Kennerley et al., 2017), while in emotional agility, patterns of thought or ‘hooks’ are identified (David, 2016). Once negative thoughts, beliefs or patterns have been identified, individuals can then assume control over their thinking to develop more beneficial patterns of behaviour. The decision to structure the course in this way was a combination of practicality (having been trained using Reflective Dialogue) and a belief in the emotional nature of human experience.

Teaching materials

Teaching materials were broken into several categories including (1) extracts from Reflective Dialogue, (2) prerecorded video lectures, (3) editable group documents shared using Google Slides and (4) advising session videos featuring KUIS learning advisors. Due to the online nature of the course, all materials were uploaded to Google Classrooms, and synchronous lessons took place on Zoom.

The extracts from Reflective Dialogue corresponded to each of the advising strategies taught. I decided to use extracts because Reflective Dialogue provides a simple description of each strategy, its purpose and an example of the strategy in use between an advisor and advisee. These example dialogues were of particular importance since less than half of my students had experienced advising previously. These dialogues thus allowed them to see when and how strategies were introduced, both practically and linguistically.

Made available ahead of class, the prerecorded video lectures were part of a flipped approach in which the students were expected to gain a general understanding of the class content before completing in-class activities to reinforce, clarify and deepen their understanding. Some of these in-class activities were completed using editable group documents to ensure that the students were working together to co-construct their understanding of the content.

The final primary teaching materials were video recordings of 10–15 minute advising sessions that generally took place between two KUIS learning advisors. An exception to this was the video used in the final assessment task, which took place between a volunteer KUIS student and an advisor. These videos were used not only to provide ‘live’ examples of advising strategies in action, but to also expose the students to a variety of speech and advising styles.

Mock-Advising

Practical components were included in the course through mock-advising sessions. These mock-advising sessions (Figure 2) were inspired from the activities done in the Advisor Education Course offered by the Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education (RILAE). During these sessions, students worked in groups of three (occasionally four), rotating between advisor, advisee and observer roles. Each advising session took place for 10 minutes in Zoom breakout rooms. Observers were asked to turn off their microphone and camera during advising to minimise distractions. Feedback was given by observers upon the conclusion of each mock-advising for approximately 3 minutes. In total, 45 minutes were assigned for the mock-advising session, but within that time, students were expected to manage the advising and feedback time by themselves.

Figure 2

A Screenshot of the Instructions for One of the Mock-Advising Sessions

Prior to participating in these practical sessions, the students were expected to have completed the Reflective Dialogue readings or watched the prerecorded video lectures to familiarise themselves with the how and why of the advising strategy assigned to that particular lesson. Time to ask me questions or raise concerns was also provided upon regrouping as a whole class. Approximately half of the course’s duration was devoted to the development of the students’ ability to use different advising strategies. As such, these practical sessions were vital to the students’ skill development. Despite the benefits, these sessions did raise some concerns.

Issues in conducting mock-advising sessions

While smaller issues may have taken place in individual sessions, there were some ongoing factors that practitioners aiming to replicate these activities should be aware of. These include (1) linguistic concerns, (2) inappropriate topic choices and (3) insufficient feedback being provided during the feedback sessions.

Linguistic concerns expressed by the students while acting as advisors mostly revolved around not knowing how to phrase their questions or move the dialogue from one topic to the next. In some cases, the language used by their partner was unintelligible, resulting in communication breakdowns which, depending on interpersonal factors, were either resolved or led to silence. Considering the cognitive load and linguistic flexibility required for intentionally structuring a dialogue in an L2, it was unsurprising that the students experienced such difficulties. However, to mitigate the difficulties they were experiencing, additional opportunities for exposure and preparation were provided. An example of this took place when the students were learning about basic advising skills. As part of their preparation, each student was assigned two of the basic advising skills (e.g., repeating and empathising) and asked to write on a shareable document two or more possible responses to a prompt. In some cases, I provided detailed comments to ensure the students understood how their responses might be understood by the advisee, and where necessary, alternative phrasing was given. For other responses, minor edits were made as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Extract From the Basic Advising Skills Activity

Predicting what may come up during an advising session is difficult, and therefore it is impossible to prepare responses to every eventuality. In connection to this, some of the initial advising sessions included topics that students taking on the role of the advisor found uncomfortable to deal with. Naturally, students have a multitude of concerns. However, concerns that require professional training to deal with, such as self-harm or those of an overly romantic nature, were deemed inappropriate for the classroom. The students were reminded on several occasions that they were all language learners with varying degrees of proficiency and that the concerns brought forth in the mock-advising sessions should be appropriate for a conversation with an ‘acquaintance.’ Additionally, the students were made aware that they had the right to refuse to answer any questions or to request a change of topic. Sentences to request these things were provided.

The final issue observed took place during the feedback sessions, in which feedback tended to be vague compliments or lacking constructiveness. While compliments support a learner’s confidence, in order to truly grow and develop, individuals need constructive criticism to identify areas for improvement they themselves may struggle to identify. A lack of scaffolding on how to provide constructive criticism was an early limitation of the mock-advising sessions. Later sessions were modified to include a feedback sheet that students filled out when observing the advising sessions. Specifically, they were used to record which advising strategies were used, give feedback on how the strategies were used and comment on whether or not the advisor’s approach was appropriate to the advisee’s needs. While commentary from the observers varied depending on individual and interpersonal factors, the introduction and subsequent modification of the feedback sheet was observed to gradually facilitate more specific and constructive verbal feedback. An example of written changes can be observed in the work done by Etsuko (pseudonym) in Figures 4 and 5. Permission was given for her materials to be shared.

Figure 4

Original Feedback Sheet and Student Comments From Lesson 8: Basic Advising Skills

Figure 5

Updated Feedback Sheet and Student Comments From Lesson 22: Positive Feedback

While examples of changes in the verbal feedback cannot be provided, anecdotally, students spoke for longer and were more specific in their comments. Instances where the advisee reaffirmed or elaborated on the feedback provided by the observer also occurred. These changes may have resulted from growing confidence and familiarity with advising; however, the feedback sheet did appear to provide students with a space to organise and recall their observations.

Finally, while nonverbal signals were more difficult to understand on Zoom, the ‘closed space’ of the breakout room gave the students a distraction-free sense of privacy in which to conduct their advising. As a teacher, I felt joining breakout rooms occasionally disrupted the flow of the advising or feedback being given. On this point, Mina agreed, suggesting that teachers should avoid surprise visits to breakout rooms. Remaining in a single room or encouraging learners to use the ‘Ask for help’ button are possible solutions.

Benefits of mock-advising

Advising is a practical skill that requires experience to grow familiar with and confident in its use. For this reason, mock-advising constituted a good portion of the interactions between students. Based on students’ midterm and final reflections, mock-advising provided them with a chance to learn from each other, particularly in regard to creating a positive, open atmosphere. Some of the strategies and approaches learned in class translated to more positive interactions outside of class as well. Many students, in their reflections, stated that they had experienced more substantial conversations with their friends and family members. Some also reported that their workplace interactions had improved. For some people like Momoyo, out-of-class practice was also incredibly helpful in gaining confidence with the use of advising strategies.

Momoyo’s perspective. I really enjoyed mock-advising because it was interactive and included personal worries that every student might experience. By sharing our concerns, we could empathise with each other. However, because the session was short, I felt it necessary to have more experiences to get used to using the advising skills. During the sessions we had to consider how to use the skills and when to use them, so we had a lot of things to consider and so I couldn’t do the session naturally (without pressure). Thus, I tried using advising skills in private conversations with friends to use the skills unconsciously. Unless we practice as we do in the mock sessions, we would not know whether using the advising skills is easy to do or not. Therefore, outputting in the session was meaningful.

Second, we could notice others’ troubles and help each other. Actually, we seldom open up about our troubles unless we have opportunities like in the mock-advising sessions. Because we are almost the same age and English learners, we could understand what feelings each other might have. Having the same experiences makes it easier to empathise as advisors and come up with possible solutions that we may be able to do. For example, I met three people who were struggling with improving English and finally gave up. I was so shocked that many people had already quit English. Without the session, I could not have noticed this fact because we are in the same class, using English together all the time. To sum up, I felt that this practical activity made us more passionate and active in thinking about how to use the skills and recognise our peers’ hidden troubles.

Amelia’s response. As Momoyo states above, ‘hidden troubles’ were openly discussed as a result of the mock-advising sessions. I was pleased to see that these sessions appeared to contribute to supportive peer relationships. Personally, it was reaffirming to hear how students felt a combination of relief and practicality in knowing that their similar experiences could be used to show empathy or support others in overcoming problems. It is reassuring to know that including small group mock-advising in the course was the right decision despite the unpredictable and potentially private nature of topics.

Mina’s perspective. Thanks to mock-advising, even in my daily life, I could find growth in my conversations compared to before taking this course. Gradually, what I learnt enabled me to sense which parts of the topic a partner would like to talk about. For example, when some of my friends talked to me about the state of their job hunting, I tended to ask some questions based on my interests, such as, ‘What kind of job are you looking for?’ However, through practical sessions, I realised that if I ask appropriate questions, they can talk about their thoughts in detail, so it is possible for them to refresh because they express and share their feelings with me. Also, I found that sometimes people do not need any advice; what they desire is sympathy. Asking questions I personally want to know the answer to can work effectively to broaden conversations. However, it might not be helpful for my partner. What I learnt is important in sessions is to find what other people want to talk about in depth. Taking into consideration a person’s situation is an essential component of coming into contact with others. Therefore, especially when dealing with people’s worries, the conversation should be meaningful for my partner and help them discover and realise new perspectives—not for myself to satisfy my concerns.

If I reflect more specifically on what I learnt during the mock-advising, I could be a fly on the wall as an observer, so that allowed me to find things that I had not been able to notice when I was acting as an advisor: For instance, an advisee’s facial expression, tone of voice and speed conveyed nonverbal messages. That is why when I was an observer, I realised that an ideal advisor should understand nonverbal messages to understand an advisee better. Also, through observing other students’ sessions, I could get several helpful and useful expressions for my turn and notice what I lacked in terms of using direct and indirect approaches. For example, my communication style was too indirect, so I should be more flexible depending on the person and situation. In addition, when my role was as an advisor, I could mainly receive feedback from the observer. Hence, I was able to reflect on my practical session from not only my subjective view, but also others’ objective perspectives. If my group had some time left, I could obtain comments from an advisee too. Personally, I guess that the time was the most precious to think back on my advising calmly because each person perceived my session differently, so how an advisee feels has to be considered first for my improvement.

Amelia’s response. Mina makes a really good point regarding the importance of understanding, interpreting and using nonverbal forms of communication. Despite the lack of lessons dedicated to expressions, tone and pace, it is encouraging to know that implicit learning took place. In addition to Mina’s point about nonverbal communication, I also believe that there were benefits in terms of language development. In particular, the cyclical nature of the advising sessions meant that the students were exposed to several opportunities for input, output and the revision of their own questions, responses and topics. In other words, despite the different focus of each mock-advising session, the concerns students brought to the table as an advisee were often similar (i.e., concerns with job hunting or managing their studies), thereby allowing students to gain familiarity with certain advising strategies or recycle phrases or questions used by their peers, just as Mina mentions doing.

Analysis of ‘Authentic’ Advising Sessions

The final component of the course I would like to share is the analysis of ‘authentic’ advising sessions. I use the word ‘authentic’ to indicate that these advising sessions were conducted and video-recorded by professional advisors. In total, there were four advising videos used. Although two videos (‘Breaking Down Goals’ and ‘Giving Positive Feedback’) were purposefully created for the course, the advisors were not bound to follow any clear structure, unlike the students’ mock-advising sessions. Rather, they were simply asked to keep the general advising aim or strategy in mind. Two preexisting videos (‘Viewpoint Switching’ and ‘Advising: Start to Finish’) were used with permission from an in-house repository of advisor training videos due to their relevance to the course. ‘Breaking Down Goals,’ ‘Giving Positive Feedback’ and ‘Viewpoint Switching’ were approximately 10 minutes long and used as pre-lesson materials. Meanwhile, ‘Advising: Start to Finish,’ a full 20-minute advising session, was used as a stimulus material for the final assessment task. With the exception of the first video (‘Breaking Down Goals’), students used the same feedback sheet as in their own mock-advising sessions to analyse the videos. As part of their analysis of the videos, they were asked to consider why the advisor used particular strategies, how these strategies appeared to have been received by the advisee and what alternative approaches they may have used if they were the advisor. There was a constant push for students to weave theory and experience into their analysis. Some of the theories, including communication styles and self-endorsed goals, were easier for students to use as analytical frames. Meanwhile, interpreting where advisees were on the learner trajectory (Kato & Mynard, 2016) caused some confusion and doubt among the students. Direct and indirect approaches were frequently mentioned by students in their analytic writing; however, there was some confusion over what constituted a direct or indirect approach and the benefits of these approaches. Future courses may need to revise these concepts frequently, and clearly differentiate between direct/indirect speech styles and direct/indirect advising approaches. Addressing personal variation on how direct and indirect approaches can be interpreted by the students may also prove worthwhile. To alleviate confusion over direct/indirect speech styles and advising approaches in particular, students may benefit from receiving annotated examples that they can refer back to later. Activities that require students to analyse and discuss short advising scripts could also be used to reinforce their understanding.

Following are Momoyo’s thoughts on analysing ‘authentic’ advising sessions.

Momoyo’s perspective. I could notice what I lacked by watching videos of advising sessions. I unconsciously tend to be direct and quick to rush to a conclusion. On the other hand, the learning advisors in the videos were much more indirect than me. Plus, by keeping silent and repeatedly asking questions, the advisor lets an advisee talk about all that they were thinking about. Such a style makes it easier for an advisee to organise their thoughts by making the atmosphere comfortable for them. Through analysis of the videos, I felt it was necessary to make the atmosphere better by listening to the advisee for a long enough time. The analysis itself was essential. However, it was difficult for me to make full use of the feedback sheet for several reasons. First, I often get confused when it comes to distinguishing the advising skills in the video, especially among repeating, restating and summarizing. Moreover, judging whether the approach matched or not was also tricky since which points to consider regarding the compatibility was unclear. For these reasons, I could not fill in all the blanks, leaving some question marks in my mind. As Amelia said in the section above, future courses may need some review of what exactly each advising approach is, and letting us know some tips to judge which is the appropriate approach may be helpful, if it is possible.

Reflections

Since it is the learners for whom a course is designed, this final section will start with Momoyo’s reflection on the course as a whole.

Momoyo’s reflection

There are many tips to be considered when advising whoever we talk to in order to make it easier to lead to a solution. By learning them, I realised that advisors have to use another brain as ‘advisors’ to make it easier for advisees to open up and find their way, not as ‘friends’ who talk casually without any purpose or just to enjoy the conversation. During this course, my way of listening to others has changed. I used to ask whatever question I came up with at that moment. However, I realized that it may not be helpful for advisees and that I can choose another question that may encourage a practical solution for them. By trying to recognise what blocks their passage towards the outcome they want and not just asking what is a curious point for me as the advisor, I can help them find a practical solution. Thus, the course taught me the importance of critical thinking to make the best road towards their goals for my advisees. Moreover, we tend to advise in a subjective way by pushing our beliefs onto others, but we need to focus on the advisee’s personality and think about issues in their place by knowing their values. Therefore, I noticed having an objective perspective by observing advisees is also an essential element in supporting them.

Amelia’s reflection

I thoroughly enjoyed teaching this course for a multitude of reasons, from the energetic dynamics of the students to the subject matter, which has shaped my own professional life. This course gave me a chance to pass on communicative strategies and approaches that I felt would allow my students to negotiate their place in the world with insight and confidence. Inviting others to open up to us, being vulnerable with ourselves and opening up to others are difficult to do. So too are listening without judgement, timing responses correctly, asking the right questions and challenging existing beliefs. My students had to learn that regardless of their perceived language capabilities, they had to place themselves second. In doing so, I felt they learned to prioritise others, to make their language accessible to their advisee’s level and to listen carefully to both the words spoken and those left unsaid. The desire to be better advisors came from students themselves, but I believe that the presence of specific skills and strategies gave them a framework to evaluate their own communicative abilities from. Having such a structure appeared to make it easier for them to identify communicative techniques that could be helpful for future interactions. In addition to evaluating their communicative abilities, advising others and observing advisor–advisee interactions seemed to create an environment in which self-reflection was everywhere. It is my sincere hope that by gaining the skills to advise, my students continue to use what they have learned to listen to, observe, consider and reflect on their interactions with others. Limiting advising to interactions with others may overshadow the need to practice self-advising, something my students have been encouraged to apply to themselves equally. In doing so, they will become better able to address any ambiguities head on and have the confidence to apply their learning fearlessly.

Conclusion

The aim of this reflection was to inspire other educators to explore ways of making advising accessible to language learners. To conclude we would like to outline some ways in which elements of this course could be modified for general language classrooms. Firstly, introducing the five basic advising skills—repeating, restating, summarising, complimenting and empathizing—could be effective in helping students to take a more active interest in their interactions with each other. In particular, summarizing, repeating and restating could be taught in line with strategies for negotiating meaning or clarifying miscommunication. Secondly, choosing roles prior to any discussion (Speaker, Supporter/Listener and Observer) could provide learners with an understanding of how it feels be in each role. The empathy developed may encourage further cooperation. For Supporter/Listeners, they are given the chance to practice their active listening skills while asking questions to deepen the speaker’s thoughts. Observers could be supported in giving feedback through the use of rubrics which can be modified to target the lesson goals.

In these small ways, we believe that advising skills can be made accessible to all language learners. We invite teachers from all backgrounds and teaching contexts to experiment with the ideas within this reflection in their own classrooms.

Notes on the Contributors

Amelia Yarwood is a Learning Advisor at Kanda University of International Studies. She has been active in planning, implementing and researching interventions to support the development of learners’ reflective capabilities, identity, motivation and autonomy. Her current goal is to complete her doctoral degree through Kansai University’s Graduate School of Foreign Language Education and Research, Japan.

Momoyo Asaizumi is a senior undergraduate student at Kanda University of International Studies. She majors in English and is currently engaged in preparing for full-time work after graduation. This is Momoyo’s first academic publication.

Mina Kawauchi is a senior undergraduate student at Kanda University of International Studies. She majors in English and is currently leading the mentor community at the university. Her research interest lies in nonverbal communication, especially silence, across countries and in hierarchical contexts. Mina plans to study differences in the interpretation of silence from the perspective of culture and social position at the graduate level once completing her undergraduate degree.

References

David, S. (2016). Emotional agility: Get unstuck, embrace change, and thrive in work and life. Penguin Life.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(6), 1024–1037. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1024

Kato, S. (2012). Professional development for learning advisors: Facilitating the intentional reflective dialogue. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(1), 74–92. https://sisaljournal.org/archives/march12/kato/

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

Kennerley, H., Kirk, J., & Westbrook, D. (2017). An introduction to cognitive behaviour therapy (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Lantolf, J. P. (Ed.). (2000). Sociocultural theory and second language learning. Oxford University Press.

Lantolf, J., & Pavlenko, A. (2001). (S)econd (L)anguage (A)ctivity theory: Understanding second language learners as people. In M. Breen (Ed.), Learner contributions to language learning: New directions in research (pp. 141–158). Longman. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315838465-16

Ryan, E. L., & Deci, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development and wellness. Guilford Press.

Ryan, S. & Dörnyei, Z. (2013). The long-term evolution of language motivation and the L2 self. In A. Berndt (Ed.), Fremdsprachen in der perspektive lebenslangen lernens (pp. 89–100). Peter Lang.

Shelton-Strong, S. J. (2020). Advising in language learning and the support of learners’ basic psychological needs: A self-determination theory perspective. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820912355

[Appendix]

Dear Amelia, Momoyo, and Mina,

Thank you very much for sharing your reflections and for this valuable contribution to our field. First and foremost, I loved that practical considerations have been placed at the center of this work (rather than being an afterthought attached at the end of a paper!). I also respected that this reflective piece had been constructed democratically and inclusively (with instructor and student as co-researchers) in keeping with the broader principles of advising and learner autonomy. I hope that we will see more studies of this format in the years to come. I felt that you all provided some fascinating insights into the simultaneous process of learning and becoming in the case of advisor training. Through your reflections, I saw numerous examples of acquiring not only technical skills and academic knowledge but also new ways of viewing and being in the world. Advising changed the students and judging by the final reflections, the students’ experiences changed Amelia too. One theoretically-oriented takeaway that I had from reading this study was how an individual’s participation in the advising course both affected and was affected by their historical learning trajectories. In Mina’s case, we can see how her past experiences as a tutor informed her beliefs, her emergent interest in helping others, and indeed her desire to join the advising course. Seeing them as congruent with her historical experiences, she internalized the techniques and “regime of competence” (Wenger, 1998) of the course in the present and then impacted the way she frames interactions with others in the future. Furthermore, an understanding of advising techniques, knowledge of relevant academic theory, and a deeper awareness of learner affect are sure to be useful not only within the specialized community of language advisors but across a broader educational landscape of practice (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015).

The idea of “hidden troubles” also resonated a great deal with me. From my experiences both as a teacher and a researcher, I feel that language learners (including myself) often tend to construct a notion of other people experiencing relatively smooth paths to language acquisition while framing themselves in deficit terms. This study raises an additional benefit of advising training – exposing the advisors themselves to the struggles almost everyone faces as language learners – that is likely to stimulate personal growth and self-reflection. Furthermore, it is conceivable that this basic truism can then be extended to any area of skill development that learners engage in throughout their lives.

While I was reading the study, a few questions did spring to mind that you may like to consider or unpack as you develop further research in this area:

The issue of power sprung to mind on a number of occasions. Do you feel that a seniority-based hierarchical structure like a senpai/kohai dynamic is fundamentally in opposition to an autonomy-supportive perspective like advising, or can these two perspectives be reconciled?

Also, the issue of language use made me wonder about the power dynamic of the course itself. Does a primarily L2 environment where advising (in the course) must be conducted in English create a power imbalance more akin to a regular language classroom (teacher-student) as opposed to a more translanguaging approach that would flatten the hierarchy somewhat? It’s not a criticism as I know there are institutional requirements to consider. I was just wondering if this dynamic might be played with in the future.

Once again, thank you very much for this thought-provoking piece of research. It made me more sure than ever of the value of advising and also put forward a lot of stimulating examples and concepts that I can apply to my own research and practice. I’m looking forward to more studies akin to this one in the future!

Dear Daniel,

Thank you for your sincere and thoughtful comments. As the teacher of this course, it makes me feel incredibly encouraged to have inspired potential changes in another educator’s practice. I can only hope that your students get as much out of advising-based activities and concepts as mine have.

Regarding your question about the issue of language and power dynamics, this was something that I had to consider early in the planning stages of this course. The course was a hard CLIL course. However, pragmatically speaking, I don’t believe that hard CLIL equates to English-only for all. Given the mental strain of dissecting patterns of behaviour, emotion and subsequent actions can be in your L1, I felt enacting an L2-only policy would undermine not only students’ learning but their chance to develop close bonds – so I didn’t. Rather, I encouraged the students to make use of some translanguaging practices where necessary. For myself, I used the L1 on materials to scaffold understanding, and L2 output.

In terms of “hidden troubles”, Mina and I had a meeting to discuss this in a little more detail. On behalf of Mina, here is a summary of what was said:

Sharing problems can be really difficult but if we can find people who we can talk to then our stress will be reduced. I am not sure if it is a nationality/cultural issue but showing weakness is sometimes embarrassing. Unconsciously, I have built a hierarchy and so if I get advice from a teacher then it is OK but in class, my peers are on the same level as me so it is more embarrassing then. It feels like I am weaker than them. I am also afraid of my weakness being shared with others and used as material for rumors. So it is all about trust and mutual respect. With teachers, they have a responsibility to me as the student. With my classmates there is only an unspoken rule (?) which can easily be broken, so trust needs to be made in the classroom. To help create that level of trust, I feel we need to make sure not to laugh or make fun of others. If the other classmates accept and respect other people’s ideas then we can trust each other more. Practically speaking, this is easier in classes that are a year long like in Freshman or seminar classes, but a lack of discussion time can contribute to a lack of mutual respect. So we need to have lots of discussion time, and we need to have more choice in who we talk to. In year-long classes, students need to feel like “this is my community” by choosing their own partners, then maybe gradually randomising groups would be better towards the end of the year.

Mina and I also spoke about the “power dynamics” issue and from Mina’s perspective, there is definitely a power imbalance in classrooms. While some teachers do ask for student voices, there is still an implicit understanding that the teacher is evaluating students. Moreover, when students are asked for their opinions, they don’t always see what happens once they give their feedback, which can make them feel like their voices aren’t being heard. In all classes, but perhaps especially in classes like this advising one where personal experiences and emotions are placed at the centre of the curriculum, teachers need to elicit student voices, but they also need to make sure that the students know their voices are actually being heard and acted upon. Open dialogue channels, and opportunities for potential misunderstandings and concerns to be addressed need to be considered. This could be one way to make a genuine effort for fairness and trust in the language classroom.

Dear Amelia, Momoyo, and Mina,

Thank you for sharing your reflection on a course you designed to introduce general advising skills and approaches at your institution. Actually, I was very excited and happy to hear about the course. While I have been involved in designing and conducting learning advisor training courses for educators and graduate level students, I always knew that advisor training could and should be implemented for undergraduate students as well. In fact, I had some advisor training components in my undergraduate learner autonomy research seminar course this year. I felt that running such courses is very worthwhile and is a promising area. Since I did not have the luxury to spend the whole 15 weeks on advising in my course, it was very interesting to hear about your course and the reflections by you and your students.

I’d like to share some of my thoughts after reading your paper. First, I agree with you on the importance of providing enough scaffolding through worksheets with specific questions when introducing advising skills. Especially when learners are carrying out these activities and constructing intentional reflective dialogues in their L2, such support can be very helpful. You mentioned about the difficulty you had when asking students to give constructive criticism to fellow students. Preparing worksheets is definitely helpful for students when giving feedback, but I also feel that giving feedback is not easy, even in their L1, when students don’t have trusting relationship with each other. As you mentioned in the literature review section of your paper too, a trusting relationship is very important in advising. I would like to hear how you tried to create that trusting relationship within your course. Have you done any activities to build trusting relationships among the classmates? Or did you encourage students to use the advising skills to build such trusting relationships through their advising dialogues?

Second, I can see from the learners’ reflections that Mina and Momoyo have strong interests and passion for supporting other learners’ language learning experiences, and their goals were achieved by taking this course. As a learning advisor and a teacher myself, I again confirmed the importance of recognizing learners’ affect and motivation in language learning education and the important roles of peers in the process.

Lastly, I thought that it would be very interesting to do a cross-institutional collaborative session someday with your students, my undergraduate students, and any other students who are interested in learning about or sharing reflections and practices on advising in language learning.