Michael Burke, Daniel Hooper, Bethan Kushida, Phoebe Lyon, Jo Mynard, Ross Sampson, Phillip Taw

Burke, M., Hooper, D., Kushida, B., Lyon, P., Mynard, J., Sampson, R., & Taw, P. (2018). Observing a social learning space: A summary of an ethnographic project in progress. Relay Journal, 1(1), 209-220. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010121

Download paginated PDF version

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

This paper is a brief summary of an ethnographic research project currently in progress. Although the authors plan to present multiple papers based on the research, this paper has been written with the purpose of documenting progress so far. The main aims are to keep colleagues informed and to ensure that all of the steps are recorded to aid future dissemination of the findings.

The authors summarize a project which started in June 2017 and will continue for several years observing student behaviors occurring in one social learning space in the Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS).

Keywords: Social learning spaces, identity, autonomy, communities

Purpose of the Research

The purpose of this paper is to provide a brief summary of a piece of research conducted in the Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) in Japan. Although the authors plan to publish several papers exploring various aspects of this project, the purpose of this summary is to document the work completed in the first year of the project. This will serve as an update for colleagues and also an end-of-year record of the research in order to guide subsequent work.

SALCs have several functions including supporting language learning, promoting learner autonomy, and developing social learning communities (Murray & Fujishima, 2013; 2015). In order to promote target language use, it is common to include a space within a SALC where students can practice using the target language in a relaxed and supportive environment.

As KUIS specializes in foreign languages, it has provided a lounge in which students can practice speaking English for the past 20 years or so. Use of the lounge is optional and although teachers are on duty to facilitate English language conversation, English practice between students (without teachers being present) is also encouraged. However, with two exceptions (Gillies, 2012; Rose & Elliot, 2010), little research has been conducted which investigates the dynamics of what actually happens within the space. As the KUIS SALC moved into a purpose-built new building (‘KUIS 8’) in April 2017, the time was right to begin a research project. Drawing on observations and interviews, the researchers explore some of these dynamics as an ethnographic study.

Underpinning Theoretical Constructs

The ontology and epistemology of the interpretative paradigm

The manner in which interpretative the paradigm has been constructed can be explained according to two concepts from the philosophy of the social sciences. First ontology, which governs questions concerning existence and being, such as “What can exist?”, “How can it exist?” And crucially, “How does it lead to consequence?” And second epistemology, which concerns questions on knowledge, such as “What can be known?” And “How can it be known?”

Ontology. This research is concerned with how the social structure overlaying the lounge influences students. This lends itself to a structuralist ontology that aims to understand, in a broad sense, how the social structure in question leads to consequence and what those consequences are. Within the scope of these consequences however, the specific focus is to discover how—and if— “the ordered social interrelationships, or the recurring patterns of social behaviour” that “… determine the nature of human action” (Parker, 2000, p. 125) cause changes in students’ identities (Block, 2017).

Epistemology. The epistemological focus of this work is to ascertain how students jointly construct knowledge based on the shared attitudes, values and practices (Schotz [1932] 1967; Winch, 1990) particular to the overlaying social structure, which lends itself to a constructivist epistemology (Hatch, 2002, pp. 15-16). By looking at the lounge’s social structure through this epistemological paradigm then, knowledge—both of and within the structure—is understood as formed subjectively, by interacting with a shared interpretation of a reality that is constructed intersubjectively by the students and teachers who use the space (Dixon & Dogan, 2005). By observing interactions between these participants, and in interviews, the hope is to better understand the nature of this reality.

Identity

The field of identity was used to frame the research as the researchers mainly wanted to understand what was happening in the English Lounge and identity research focuses in particular on features of human behavior. Most linguists writing about identity and second language learning take a poststructuralist approach (e.g. Block, 2007; Norton, 2000) which is a nuanced, multi-levelled and complicated framing of the world that originally emerged from the field of sociology. A poststructuralist approach sees identity as the product of the social conditions in and under which it was developed (Block, 2007). In addition, the approach suggests that individuals are determined by membership of social categories, which is relevant in our context. Although the purpose of the ethnography is to observe behaviors in the English Lounge, the researchers are likely to initiate change in collaboration with the participants and according to a poststructuralist view of identity, environmental factors can be changed in order to make improvements to a society, this in turn can influence people.

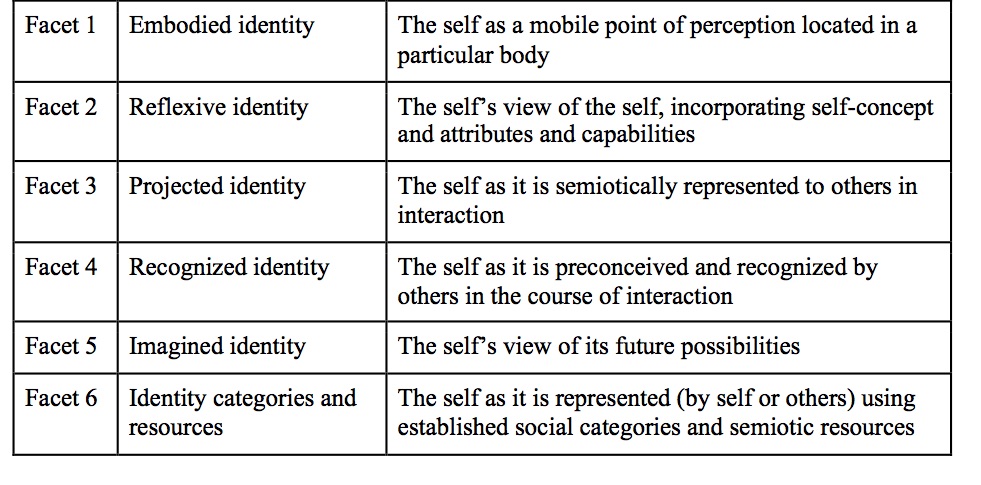

The research draws on discursive construction of ideas (e.g. Gee, 1996; Miller, 2014; Weedon, 1997) and performativity (e.g. Goffman, 1959; Miller, 2014), but was influenced in particular by work by Benson, Barkhuizen, Bodycott, and Brown, (2013) who investigated identity according to six facets (summarized in Table 1).

Table 1. Facets of Identity (From Benson et al., 2013, p. 19)

Communities of Practice

Communities of practice (COPs) are “groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly” (Wenger & Trayner, 2015, p. 1). Different members engaging in varying degrees of participation in a community’s shared endeavors is a key feature within a COP framework and it was this that led the researchers to consider analyzing the behavior of English Lounge users through this theoretical lens.

A further reason for adopting the COP framework was that it provided the researchers with an established theoretical ‘roadmap’ for identifying, categorizing, and analyzing key features of the English Lounge community. Wenger and Trayner (2015) argue that a COP consists of three key elements – Domain, Community, and Practice. They claim “it is by developing these three elements in parallel that one cultivates such a community” (Wenger & Trayner, 2015, p. 2).

Finally, research into COPs often foregrounds issues of identity, interdependence, accountability, and self-sustainability among community members (Wenger, 1998; Wenger, McDermott, & Snyder, 2002). The authors found that this was reflected in a growing focus on community building within the field of self-access learning, where the COP framework had been adopted in a number of studies (Bibby, Jolley, & Shiobara, 2016; Gillies, 2010; Murray & Fujishima, 2013), thus justifying its use in the analysis of the English Lounge.

Part 1: The Observation Study

Observation Study: Purpose, Methods and Instrument

A total of ten observations of the social learning space were conducted over a period of two weeks as part of the initial information gathering process to determine how the space is being used. An observation form was designed based on Spradley’s (1980) “9 Dimensions of descriptive observation” framework (space, actors, activities, objects, acts, events, time, goals and feelings) with additional considerations drawing on the literature on identity (Benson et al., Block, 2007; Norton, 2000) and communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 1998).

Before the observations commenced, a map was produced of the area that was divided into sections to make it easier to note down the activities in the area during each 90-minute observation period. Since all seven researchers would be conducting observations, a secondary role of the map was to help with observation consistency. Researchers signed up in advance to perform observations in order to cover as many days of the week and times of day as possible. Whilst conducting observations, researchers took notes, guided by, but not limited to the items and questions provided on the observation forms. The observations were conducted in the form of “participant observation”, whereby the researchers were active participants in the setting (Hatch, 2002). Although some notes were taken in real time, students (and instructors on duty) were not informed about the observation process. This was done to reduce the possibility of the observations affecting results. As such, an ethics form was completed and submitted to the Institutional Review Board to ensure ethics standards were met. Raw field notes were typed up as soon as possible after the observation and saved in a Google Folder. These notes included not only what was observed, with time stamps to help show the sequence of events, but also researchers’ impressions, assumptions, intuitions and reflections (Hatch, 2002). Once the observation was completed, three members of the research team conducted a qualitative analysis of emergent themes observed using a piece of software called HyperResearch.

Observation Study: Brief Findings

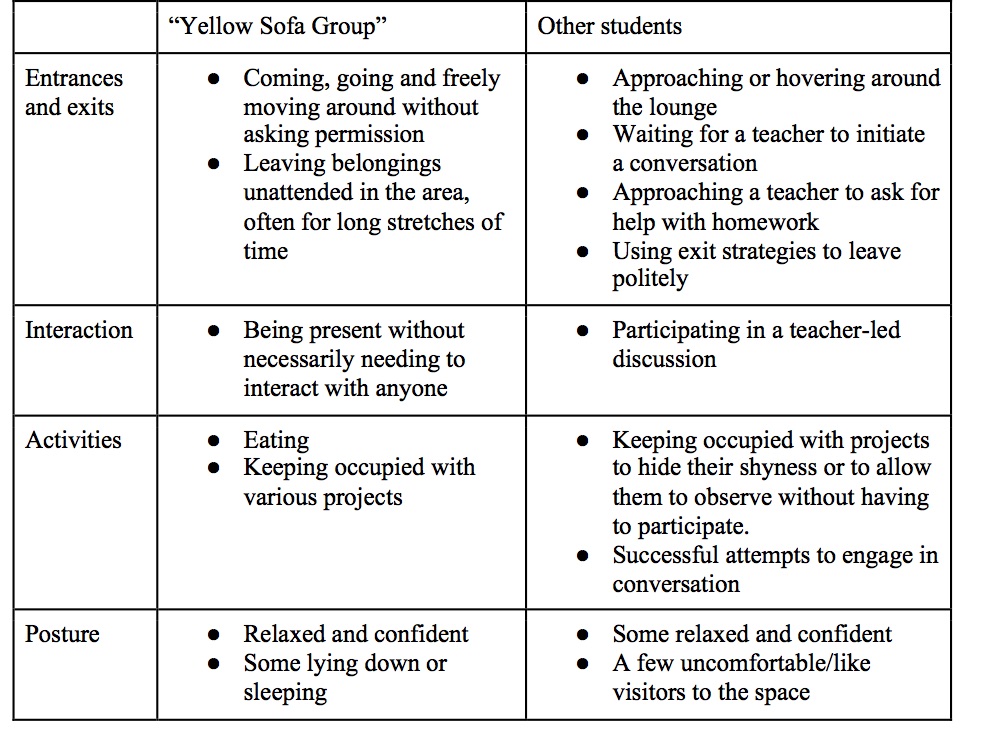

A total of 45 codes emerged from 378 items. Although the observation data included notes on the activities of teachers and international students who were in or passing through the space, the analysis focused on KUIS students. Through this analysis, it was possible to identify a distinct subset of behaviors exhibited by a core group of highly frequent users, which differentiated them from the other students using the lounge. The name “Yellow Sofa (YS) Group” (taken from the lounge’s unofficial name) was selected to indicate these highly frequent users. At this stage it was difficult to distinguish through the observation data alone whether the other students were frequent users or non-frequent users of the space.

The “YS Group” appeared comfortable in the space and their observed behaviors seemed to demonstrate a sense of ownership and belonging, whereas the behaviors of the other students created the impression that they revolved around the teacher as the facilitator. The most frequently observed behaviors for each group can be summarized as follows (Table 2):

Table 2. Most Frequently Observed Behaviors

Part 2: The Interviews

The Interviews: Instruments, Methods and Participants

The individual interviews conducted for data collection were all of a semi-structured format. This style of interview allows for the interviewer to guide the interview while also allowing the interviewee to elaborate on issues, therefore not limiting depth of respondents’ stories (Dörnyei, 2007, p. 136). The reasons for this were that there were a number of questions mainly pertaining to learner identity, which were regarded as essential to the direction of the research.

The interviews lasted between twenty and forty minutes, recorded with the consent of the participants and transcribed afterwards. A total of fifteen interviews were conducted consisting of first to fourth year students at KUIS. The participants were recruited through advertisements posted in the lounge itself and by an invitation emailed to whole class groups. In the response form, the students reported their frequency of use. This together with the researchers’ personal knowledge of the users of the lounge, enabled three groups to be identified. These were organized in order of frequency of use, with the YS Group (five students interviewed) as the most frequent, followed by frequent users (FU) (six students interviewed) and non-users (NU) (four students interviewed). Three sets of interview questions were prepared, each tailored to one of these groups.

Data Analysis

The interview data were analysed in three ways allowing for different perspectives. Firstly, three of the researchers undertook a typological analysis (Hatch, 2002) ensuring that the interview themes related to identity were analysed. Secondly, four of the researchers analysed the same interview data using a COP framework. Finally, an interpretative analysis (Hatch, 2012) was conducted by four of the researchers in order to allow for other emergent themes to be explored that were not necessarily related to identity or COP. This analysis is still in progress, but all of the researchers are involved in the process. Details of the typological and the COP analysis along with brief findings will be given in the next sections.

Typological analysis and findings

A typological analysis of the transcripts (Hatch, 2002) involved answering questions aimed at understanding student participants’ perceptions of both the conversation lounge and themselves. The analysis related to the facets of identity discussed above (Benson et al., 2013).

There were a number of responses to the question of “how do you view the role of the lounge?”. These included:

- English practice

- Improving English

- Self expression

- Relaxing

- Having fun

- Meeting / Making friends

- Talking to others

However, when looking at the manner in which each identified group differed in their view of the role of the lounge, the purpose seemed quite different. The YS Group viewed it as a place to “hang out” and somewhere to meet other similarly motivated individuals. The FU Group mainly saw the lounge as a place with a functional use where you can interact with native speakers. The NU group mostly saw the role of the lounge as a place for English conversation, however some of their opinions indicated that they did not see it as a language learning resource for them.

In regards to identity, the overarching theme of this research, there were clear distinctions found when analyzing how student participants viewed themselves. The YS Group seemed to express confidence in their interviews. They appeared to seek recognition as ‘role models’ for younger students often claiming to actively invite other students into the conversation area, in order to mitigate the perception of their group as somewhat closed off and inaccessible to outsiders. In comparison, among the FU Group there seemed to be a lack of confidence with regards to both English proficiency and interacting in the wider social environment. However, students in this group also expressed motivation for using English. The NU Group had more individual answers and thus their reflexive self-perceptions could not be categorized easily. For “projected identity”, the YS Group generally seem to want others to regard them in the same way they view themselves, as confident and approachable English language users.

The findings of the typological analysis seem to reveal the dynamics of a structuralist ontology. Generalizable themes might likely have been identified in YS Group because they play the largest part in the creation of the intersubjective reality common to their social structure, these themes might not then be so easily found in the other groups because they are not so similarly invested and might thereby be more influenced by other structures from elsewhere.

Communities of Practice analysis and findings

As previously stated, following the initial observation study of the English Lounge, a number of distinct patterns of use emerged that categorized users into two distinct groups – a core (YS) group and frequent, but less active users (FU). The researchers discovered that these groups corresponded, in part, to the concept of peripheral and full participation from the COP literature (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger, McDermott, & Snyder, 2002), thus prompting them to incorporate the COP model into the study. Upon thematically coding the transcribed interview data from both YS and FU groups, salient features were identified within the data that corresponded with Domain, Community, and Practice – three key elements that are claimed to constitute a COP (Wenger et al., 2002; Wenger & Trayner, 2015). Interpreting participants’ engagement in the English Lounge in relation to these three elements gave the researchers a robust set of criteria for analyzing the interview data.

Domain. In Wenger and Trayner’s terms, a COP features a “shared domain of interest” and “membership therefore implies a commitment to the domain, and therefore a shared competence that distinguishes members from other people” (Wenger & Trayner, 2015, p. 2). In the English Lounge interview data, researchers were able to identify several themes that suggested participants’ membership in such a domain. Two of the key findings that emerged were: (1) the presence of an imagined community in which core members shared certain perceived traits, and ( a shared belief within the Lounge related to the desired approach to, and motivation for, language learning.

Community. Community describes the way in which members of a COP engage in a shared endeavor while supporting each other and sharing information (Wenger & Trayner, 2015). There also seemed to be a sense of awareness of each member’s status in relation to one another and their place in the COP. The researchers discovered numerous instances of participants exhibiting awareness of their place in the English Lounge community and the corresponding responsibilities they felt were tied to that positionality. Furthermore, core YS Group members were frequently mentioned by more peripheral FU members as a source of motivation and guidance and may have inhabited a role akin to near-peer role models (Murphey, 1998).

Practice. Within a COP, practice refers to a shared repertoire of “experiences, stories, tools, ways of addressing recurring problems” (Wenger & Trayner, 2015, p. 2). Perhaps the most salient forms that practice took in the interview data demonstrated awareness by most YS Group members of problems of integration existing in the community, problems that they faced in the past as formerly peripheral COP members. YS Group members shared several steps they had taken in response to this concern. Crucially, the YS Group appeared highly motivated to preserve the future of their community by constructing additional points of entry for new members and opportunities for socialization into the group.

Directions for Future Research

As mentioned earlier, this research project, which involves observing student behaviors occurring in one social learning space in the SALC at KUIS, is one that will continue for several years. One consideration for this is, as students progress through the university cycle, many of the participants in the current study will phase themselves out out and new participants will join. Taking into account these natural progressions will provide a more comprehensive and longitudinal understanding of the social learning space. Also, as feedback in regards to the lounge is provided by the students and their suggestions, if any, are subsequently implemented, further data collection will be required to assess the impact of any changes on the space. This would require the research team to conduct follow-up observations of the lounge as well as conduct follow-up interviews of the YS and FU groups to understand how and whether their identity in regards to their English use has changed, along with their perceptions of the lounge. In addition to the above, case studies might also better reveal the ontological dynamic wherein structure influences agency and combined agency shapes structure. New colleagues will also be invited to participate in the research.

Notes on the contributors

Mike Burke is a lecturer of the ELI at KUIS. He completed an MA in TESOL at University of Nottingham, UK.

Daniel Hooper is a lecturer of the ELI at KUIS. He completed an MA in TESOL at Kanda University of International Studies.

Bethan Kushida is a principal lecturer of the ELI at KUIS. She completed an MA in Advanced Japanese Studies at the University of Sheffield, UK.

Phoebe Lyon is a principal lecturer of the ELI at KUIS. She completed a PGCE in Education at Monash University, Australia and an MA in Education with a focus in TESOL at Deakin University, Australia.

Jo Mynard is an associate professor and Director of the SALC at KUIS. She completed an M.Phil. in Applied Linguistics at Trinity College, University of Dublin and an Ed.D. in TEFL at the University of Exeter, UK.

Ross Sampson is a lecturer of the ELI at KUIS. He completed an MEd in TESOL at University of Glasgow, Scotland, UK.

Phillip Taw is a lecturer in the ELI at KUIS. He completed an M.A. in TESOL at California State University, East Bay, USA.

References

Benson, P., Barkhuizen, G., Bodycott, P., & Brown, J. (2013). Second language narratives in study abroad. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bibby, S., Jolley, K., & Shiobara, F. (2016). Increasing attendance in a self-access language lounge. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(3), 301-311. https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep16/bibby_jolley_shiobara/

Block, D. (2017). Second language identities. London, UK. Continuum.

Dixon, J., & Dogan, R. (2005). The contending perspectives on public management: A philosophical investigation. International Public Management Journal, 8(1), 1-21.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodologies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Gee, P. (1996). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses. London, UK: Falmer.

Gillies, H. (2010). Listening to the learner: A qualitative investigation of motivation for embracing or avoiding the use of self-access centres. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(3), 189-211. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/dec10/gillies/

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York, NY: Anchor.

Hatch, H. (2002). Doing qualitative research in education settings. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, E. R. (2014). The language of adult immigrants: Agency in the making. Bristol, UK. Multilingual Matters.

Murphey, T. (1998). Motivating with near peer role models. In B. Visgatis (Ed.), On JALT ’97: Trends and transitions (pp. 205-209). Tokyo, Japan: JALT.

Murray, G., & Fujishima, N. (2013). Social language learning spaces: Affordances in a community of learners. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 36(1), 141-157. doi:10.1515/cjal-2013-0009

Murray, G., & Fujishima, N. (Eds.) (2016). Social spaces for language learning: Stories from the L-café. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning. London, UK: Longman.

Parker, J. (2000). Structuration. Buckingham, UK: Open University.

Rose, H., & Elliott, R. (2010). An investigation of student use of a self-access English-only speaking area. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(1), 32-46. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/jun10/rose_elliott/

Schutz [1932] 1967. The phenomenology of the social world. Evanston, Il: Northwestern University Press.

Spradley, J. P. (1980). Participant observation. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Weedon, C. (1997). Feminist practice and poststructuralist theory (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. M. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Wenger-Trayner, E., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). Communities of practice: A brief introduction. Retrieved from http://wenger-trayner.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/07-Brief-introduction-to-communities-of-practice.pdf

Winch, P. (1990). The idea of social science and its relation to philosophy (2d ed). London, UK: Routledge.

I would like to congratulate the research team for undertaking this initiative. There is a need for long term inquiries into social learning spaces as well as a need for ethnographies documenting these environments. I especially like the idea of a research team with the potential to become a community of practice. Furthermore, I believe that a community of practice perspective is an appropriate launching point for a study examining a social learning space. Capra and Luisi (2014) contend that a social “organization’s aliveness resides in its communities of practice” (p. 317).

One thing that caught my attention was the language of causation. I feel this is one area that requires careful investigation and deep reflection. In our experience in the social learning space at Okayama University, we have witnessed changes in students’ identity over a four-year period that have left us amazed. One instance stands out in my mind above all others.

When Eri first came to the English Café, she was fresh out of high school. She joined my weekly discussion group, but sat on the periphery, smiling, mostly silent. Over the next four years, she blossomed into a self-possessed young woman, confident to express herself in English. (For what it’s worth, she never had the opportunity to study abroad.) One day before she graduated, I commented on how she had changed during her years at the university and asked her what role felt her participation at the English Café had played. Her response was that it had definitely played a role, but there were other things, as well. I didn’t press her. Something in her nonverbal communication suggested these might be profoundly personal things. My point is that, with life and learning being complex processes with so many elements coming into play, determining causation becomes a very tricky business.

Concerning the Yellow Sofa Group, I wonder to what extent identifying as a member or a non-member of this group will be an issue. It seems to me that the YS Group has appropriated a space and transformed it into their place. I wonder about the twin issues of entry and access, which arose in our social learning space and have already come to light in interviews with your participants. I see a paper here. I would recommend reading Gee (2005) and – at the risk of coming across as totally self-promotional – Murray, Fujishima and Uzuka (2018).

As you suggest in the section on directions for future research, I think it would be a good idea to have a parallel inquiry, a longitudinal multiple-case study, tracking the identity development trajectory of members of the YS Group and the FU Group, and possibly even the NU Group (although I suspect the logistics surrounding including this third group could be a challenge).

In the future research directions section, you also refer to the issue of students coming and going, in keeping with the university time cycle. It will be interesting see how the social learning space renews itself. Also, I assume that, given the contract cycle for staff at your university, members of the researcher team will also come and go. Therefore, I believe it would be interesting – not to mention an ideal opportunity – to carry out a unique longitudinal ethnography (or a narrative inquiry or a combination of the two) focusing on the research project itself. Questions to look at might include the following:

1. Does the research team develop a group identity and how does this change over time?

2. Does the research group itself become a community of practice? How does this enfold?

3. How does internal redundancy, or lack thereof, impact the research group?

4. How does the research group renew itself over time?

5. What impact does involvement in this project have on the identity development of the individual members of the group as researchers, teachers, and/or learning centre staff?

6. How does the individual team members’ interpretative analysis contribute to an evolving theoretical orientation for the project, i.e., the group as a whole?

In the ontology section you raise the question of “how the social structure overlaying the lounge influences students”. Other related questions that I would be interested in asking are the following:

1. How do the students and the others present (teachers?) constitute the social structure?

2. How do the ways in which the YS, FU and NU Groups define the lounge determine their activities there and, concomitantly, the emergent affordances for language learning and identity development?

3. How does the space under study (spatially, you have set the parameters for your study as the area referred to, or known as, the English conversation lounge) fit into the larger space within which it is nested? I wonder to what extent it might be beneficial (or perhaps even necessary at some point) to have a parallel study examining usage of the larger space – I assume this would be largely the domain of the NU Group and to some extent that of the FU Group.

4. What impact has carrying out the research had on the social structure of the space itself?

As my reflections no doubt suggest, I see unlimited potential surrounding this project. As it stands, among other things, I am impressed by the thoroughness of the data interpretation format. I am looking forward to reading a report on the interpretative analysis when it becomes available. Another interesting aspect for me will be to see how the theoretical orientation, guiding the interpretation of the data, evolves over time. Needless to say, I am hopeful that we will be hearing a lot more about this exciting project – and others like it – over the coming years.

References

Capra, F., & Luisi, P. L. (2014). The systems view of life: A unifying vision. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gee, J.P. (2005). Semiotic social spaces and affinity spaces: From The Age of Mythology to today’s schools. In D. Barton & K. Tusting (Eds.), Beyond communities of practice: Language, power and social context (pp. 214–232). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Murray, G., Fujishima, N., & Uzuka. M. (2018). Social learning spaces and the invisible fence. In G. Murray & T. Lamb (Eds.), Space, place and autonomy in language learning (pp. 233–246). London: Routledge.

Your feedback here is extremely useful and we really are most grateful to receive it.

First, with regards to your comments on ontology and causation, this is a problem we are acutely aware of. Causation is notoriously difficult as it is clearly impossible to keep track of all the myriad of influences that might have an impact on a student’s decision to do a thing or see themselves in a particular way. Evidently then, how we attribute causation, and to what extent, requires a robust discussion that we could not deliver in the paper due to length restrictions. Our current plan is to dedicate an entire chapter in a hopefully forthcoming book to discussing these ontological considerations along with their epistemological counterparts in the detail they deserve, so as to make the underlying philosophy behind the project clearer. Should you be interested, I would be very happy to send you draft of this chapter as soon as it is ready.

Second, I was particularly interested then to read your chapter on the “invisible fence” (Murray, Fujishima and Uzuka, 2018), it strikes us as as much as a barrier as it did you. This invisible fence is perhaps not at as alien as we might initially imagine, indeed I — as the lead author — feel it when writing this response: you are more experienced, well-read and knowledgeable on this subject than I, so it is not without some trepidation, and hopefully courage, that I risk revealing my embarrassing degree of ignorance. Suffice to say then that I am much relieved and grateful for the charity of your feedback, I am also very much interested in exploring further the nature of this invisible fence.

In addition to the above, I also found your discussion on heterotopia (Murray, Fujishima and Uzuka, 2018) particularly interesting. Whether our social learning space is in the minds of different students’ “several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible” (Foccault 1984), is very much worthy of serious investigation. Evidently different subjective and intersubjective filters generate different views of the nature of any given space, but it remains to be seen whether these views constitute what could be described as incompatible realities. Again citing our exchange of views here as an example, your interpretation of the reality we are currently sharing here must to some degree subjectively differ to mine, lest it would be of no value as I could not learn anything from you. That it very much is of value must mean that the intersubjective dimension is strong enough for me to understand your points and to take them on board for future directions in research, not least for the purpose of examining the very concept of heterotopia itself. So while our realities are different, they are, mercifully, not incompatible. Of course whether or not this is reflected in our students’ experiences of the social learning space is another question entirely, but I hope we find that they find their peers as instructive and welcoming as I find your feedback here.

Finally, I found the discussion presented in Gee (2005) on semiotic and affinity spaces very useful, along with your investigation into nexuses of practice, too. Having read your chapter (Murray, Fujishima and Uzuka, 2018), I too very much see communities of practice emerging from and collapsing into a wider context of semiotic spaces or nexuses of practice, and these concepts will be highly useful for future investigation, particularly into the frequent users and non-users.

Based on the above, along with exploring the idea of our team as a community of practice and including the research questions you suggest, I would like to amend the future directions for research section of our paper in order to best take advantage of the insights you have provided.

This really is a tremendously useful review, we are extremely grateful for the effort and thought that has been put into it!

References

Foccault, M. (1984). Of other spaces, trans. J. Miskowiec. In Architecture/ Mouvement/ Continuité [online]. Available at: http://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/foucault1.pdf [Accessed 21 Feb. 2018].

Gee, J.P. (2005). Semiotic social spaces and affinity spaces: From The Age of Mythology to today’s schools. In D. Barton & K. Tusting (Eds.), Beyond communities of practice: Language, power and social context (pp. 214–232). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Murray, G., Fujishima, N., & Uzuka. M. (2018). Social learning spaces and the invisible fence. In G. Murray & T. Lamb (Eds.), Space, place and autonomy in language learning (pp. 233–246). London: Routledge.

I am happy to read that you found my comments helpful. I would be very interested in reading other articles related to your study. Please alert me to these as they become available.