Tomoya Shirakawa, Kanda University of International Studies

Shirakawa, T. (2018). Categorizing findings on language tutor autonomy (LTA) from interviews. Relay Journal, 1(1), 236-246. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010123

Download paginated PDF version

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

Language Tutor Autonomy (LTA) is a new area of research and spans a wide range of social contexts with important implications. Anyone can be a tutor, and by doing so, they can learn by teaching. LTA can potentially may have many practical applications and, therefore, should be subject to further investigation. This study used interviews to understand LTA from the tutors’ perspective. The context was a peer tutoring program at an international university in Japan specializing in self-access learning. 11 tutors participated in the research, who are all undergraduate (2nd to 4th year) students enrolled in the university. A qualitative approach using semi-structured interviews was employed in order to understand how their teaching as tutors influences their learning as students, and, primarily, to identify unique aspects of LTA. The results were organized according to interview questions concerning: (1) dealing with difficulty, (2) preparing for weekly sessions, (3) sharing experiences (beyond teaching English) and (4) developing personally from the tutoring experience. The paper will offer a model of LTA and a framework for future research and practical applications in self-access learning settings, including peer teaching and learning advising.

Keywords: autonomy, peer tutoring, self-access learning

Literature Review

Recently, there has been an increasing interest in self-access learning. While the mainstream of research on language learning is in the classroom, Benson (2011; 2017) introduces the term ‘language learning beyond the classroom’ to make an attempt to define the concept. Although the term ‘language learning beyond the classroom’ is used to cover a wide range of related fields, it would be fair to consider the term has a lot in common with self-access learning. Benson (2011) identifies four dimensions of language learning beyond the classroom; location, formality, pedagogy, and locus of control. Applying these dimensions to self-access learning, it could be said that self-access learning is generally non-instructed, independent of organized courses, takes place outside the classroom, and requires learners’ own decision making.

Furthermore, within the field of self-access learning, autonomy is the underlying goal. Since this paper examines tutors’ autonomy, it is necessary to first explore the topic of learner autonomy here. While the definition of learner autonomy has not reached complete consensus, there is general agreement with Benson’s (2007) definition which views learner autonomy as “the capacity to take control of one’s own learning”. Also, in relation to learner autonomy, studies on teacher autonomy are gaining interest and are also relevant to the present research. Little (1995, p. 179) summarizes teacher autonomy using three key elements; responsibility for their teaching, control of their teaching development and freedom from constrains.

Researchers have been studying of autonomy for some years and during this process, various types of learning approaches have also been developed. Peer tutoring, on which the present research focuses, is one of the learning approaches that has developed due to the interest in autonomous or self-access learning. Topping (2005) defines peer tutoring as follows:

The acquisition of knowledge and skill through active helping and supporting among status equals or matched companions. It involves people from similar social groupings who are not professional teachers helping each other to learn and learning themselves by so doing. (Topping, 2005, p. 631)

This definition describes the characteristics of peer tutoring which have been applied to the present research study. It is interesting that the definition emphasizes the significance of the receptive process with the use of the term “acquisition” rather than teaching process. In addition, it is clearly mentioned that the purpose of tutoring is to learn by teaching. Topping also differentiates peer tutoring from a similar learning approach, cooperative learning. One of the characteristics of peer tutoring is its role-taking, and therefore, in peer tutoring, it is always clear that there are two distinct roles as tutor and tutee in contrast to cooperative learning where learners equally work together for a shared goal (Topping, 2005).

Turning once more to the concept of teacher autonomy, it is worth noting that Smith’s term “teacher-learner autonomy” (n.d.) could emphasize the difference between tutors and teachers. According to the research, autonomous teachers self-directedly engage in developing their professional teaching skills (Smith, n.d.). However, although training sessions are provided for tutors, participation in these sessions is mandatory. Hence, there is a difference between teachers and tutors in terms of their professionality in that tutors’ commitment to developing their teaching skill is not necessarily self-directed. However, it needs to be noted that more research concerning this area is necessary since some tutors might make efforts to develop their teaching or facilitation skills by themselves.

The Initial motivation to undertake this research was from the researcher myself being a tutor, and while doing the tutoring sessions, I noticed a sense of autonomy which is different from either learner autonomy or teacher autonomy. Unlike teachers, tutors do not need to be professional teachers. However, it is true that they are required to take a certain degree of responsibility for student learning. Simultaneously, they are university students, so they are learners. Peer tutoring is a system for learners to learn by teaching (Mynard & Almarzouqi, 2006), so it can be implied that the position of tutors is placed somewhere in between teachers and learners. Furthermore, I assumed that the autonomy that belongs to tutors could be situated somewhere in between learner autonomy and teacher autonomy.

Looking now at the literature related to tutoring, research by Ruegg, Sudo, Takeuchi, and Sato (2017) conducted at Akita International University (AIU) highlights the benefits of tutors and tutees. According to the research, tutees gradually became independent and increased motivation. Thus, it could be said that the tutees developed their autonomy through the peer tutoring program. In addition, tutors could enhance their communication and leadership skills together with their knowledge about the subject because of opportunities provided by the university institution and feedback from tutees. Tutees’ feedback and expectations seem to be the biggest reason that tutors could deepen their knowledge and understandings because they were expected to have more advanced skills and knowledge than tutees. In addition, they were asked unpredictable questions during the sessions (Ruegg, et al., 2017).

The context of the research by Ruegg, et al. (2017) and this research is similar in that both were conducted in international universities. AIU and Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) where the purpose of peer tutoring is language learning; both studies present benefits of a tutoring program. However, this research is different in that the focus is only on tutors because this research pays close attention to autonomy belonging to them, and also it attempts to suggest implications which may have broader application to language learning.

Hence, the focus of this research is on the autonomy of tutors which I call in this paper ‘Language Tutor Autonomy’ (LTA). The intention of the research is to make space for the idea of LTA. Therefore, this research attempts to conceptualize the findings from interviews in order to create a foundational framework for identifying the concept of LTA.

The Context

This research focuses on the “Peer Tutor Program” which is organized by Academic Success Center (ASC) at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS). Students who are in the supporting role are called ‘tutor’, and those who receive their support are called ‘tutee’. At the time this research was conducted, there were 37 tutors. They engage in 10 sessions a semester in a fixed group of three to four students (one tutor and two to three tutees). Although there is no requirement to become a tutor, students who wish to be tutors need to take an interview test at the beginning of a semester. ASC provides three courses based on tutees’ needs: the TOEFL program, TOEIC program and Basic English program. Tutors are assigned to those programs according to their skills and experiences.

Methodology

Participants

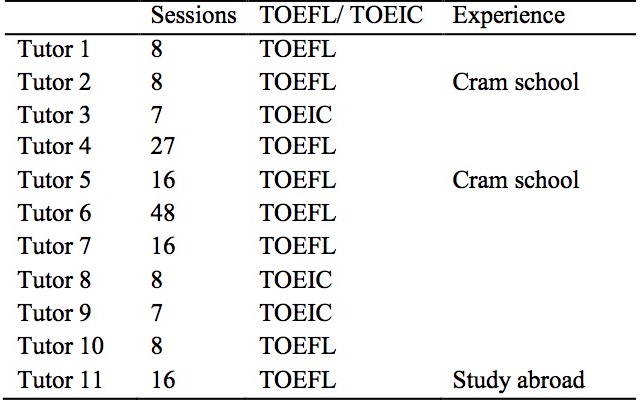

The participants were randomly chosen from all the tutors, and 11 tutors were willing to contribute to the present research. They were second to fourth-year students who were active tutors. One of the participants has experienced long-term (one year) study abroad, and two of them have worked in a cram school. Their experiences are summarized in Table 1.

There are 10 sessions a semester, and the participants had finished the 7th or 8th session at the time the interviews were conducted. Tutors are in charge of 1 or 2 sessions a week, so for example, if a tutor had two sessions a week, he/she will have completed 20 sessions by the end of the semester. Some of them are in their second year of tutoring, and the others are in their first year. Also, the participants were either TOEFL tutors or TOEIC tutors. They were provided a consent form before the interview, and they all agreed that any information which may help specify an individual such as names or ages will be kept confidential and their learning experience might be mentioned in the paper.

Table 1. The number of sessions completed by each tutor and their tutoring area and relevant experience

Data collection

Data collection

Qualitative research was considered the most appropriate approach for this research as it allows us to investigate the experience and perceptions. In addition, as this research applies qualitative approaches, the interview was chosen as a means to collect data. Interviews enable researchers to reach people’s subjective experiences and attitudes (Perakyla & Ruusuvuori, 2011). More specifically, the semi-structured interview was employed as there is flexibility in the way questions are asked (Perakyla & Ruusuvuori, 2011). Several questions were prepared in advance and occasionally further questions were asked by the researcher when they seemed necessary or interesting to ask. Since this research aims to collect people’s experiences and internal perspectives, the research questions were designed so that the perception of tutors could be obtained. The interviews were conducted in Japanese because the tutoring sessions are carried out in Japanese, and their English ability is not included in the focus of this research.

Results

The interviews were conducted in Japanese, audio-recorded and transcribed. Only responses quoted here have been translated into English. Notable responses that repeatedly emerged from different participants or indicate any significance related to the theme of this research are noted here. In addition, a short analysis is stated below each response.

Question 1: Do you find any difficulty in the tutoring session, and how do you deal with it?

1) “It is gradually getting better, but the distance between me and tutees was a difficulty at first. They look nervous, so I allow some time to have a free-talk.” (Tutor 5)

2) “They (tutees) don’t say when they don’t understand. They just say “yes”, but I am not sure whether or not they actually understand, so I ask them why they chose the answer.” (When they study grammar) (Tutor 10)

3) “I spend too much time on preparation, so time is something I’m trying to manage.” (Tutor 2)

Responses (1) and (2) indicate that tutors struggle with how to deal with the invisible wall between tutors and tutees. It can be assumed that Tutor 10 in response (2) developed a strategy in order to check tutees’ understanding. As the tutor mentioned, when tutors ask, “Do you understand?” tutees say “Yes,” so tutor 10 checks their understanding by asking the reason of their choice because they should be able to answer the reason when they understand. Also, response (3) has a problem with time management.

Question 2: How do you prepare for the weekly session?

4) “I try the questions first, and then I prepare explanations for each question.” (Tutor 4)

5) “I have to explain the reason, so I get ready to be able to explain every question. Also, I search the Internet so that I can add extra information.” (Tutor 8)

It can be inferred from responses (4) and (5) that tutor preparation involved not only looking at questions in advance but also sufficiently understanding them so that they can explain reasons in the next session. It is interesting that one tutor checks tutees’ understandings by having them explain reasons for their answers as seen in response (2) in question 1. However, the same principle works for tutors as well. Tutors ensure that they themselves can explain the reasons to check whether or not they fully understand. It could be said that this process is what peer tutoring aims for: learning by teaching.

Question 3: Do you tell or teach anything besides English?

6) “I teach how I learned English, for example using DVDs or reading novels. TOEFL is not very exciting and I don’t want them (tutees) to study only for TOEFL. I want them to have some fun while studying.” (Tutor 8)

7) “TOEFL is just a test, so I tell them my experience of being abroad or how I studied English, and they seem very interested in it.” (Tutor 11)

Response (6) implies that this tutor shares personal learning experiences and tries to motivate tutees based on his/her own belief. Sharing learning experiences would benefit tutees because tutors have experienced that they have improved their English and they know how to use resources and materials in the university. Moreover, it can be suggested that this tutor implicitly tries to develop tutees’ autonomy in that what the tutor shares may be useful when tutees learn English by themselves. Also, the tutor who gave response (7) talks about the experience of being abroad. As many first-year students wish to go abroad, this could be motivating information for tutees.

Question 4: Is there anything that you developed or improved about yourself?

This question was quite abstract and there were a variety of responses. Therefore, answers are distributed into two themes; skill improvement and motivation.

Skill improvement:

8) “My understanding of grammar has become deeper because I have to explain reasons and how to get the correct answer, so I need to really understand.” (Tutor 3)

9) “I realized that I didn’t really understand. I didn’t really think of reasons, so now, though I am still not good, at least I am better than before.” (Tutor 2)

These comments indicate that the tutors noticed the gap between their current grammar knowledge and the understanding that they need to obtain. Simultaneously, it would be assured that they make an effort to develop their grammar skills. It is worth repeating here that they develop their skills by explaining and the process of tutors’ understanding and developing grammar originates from an attempt to explain.

Motivation:

10) “I personally think the reason I do tutoring is to get myself motivated.”(Tutor 8)

11) “I make a brief plan every time, like from goal setting to reflection, which is like feedback.” (Tutor 9)

12) “One of my tutees is better at listening than me, so it makes me think I have to make an effort.”(Tutor 10)

Responses (10) through (12) noticeably illustrate that certain motivations emerge there. Tutors make themselves motivated by teaching, and furthermore, they are stimulated by tutees’ effort.

Discussion

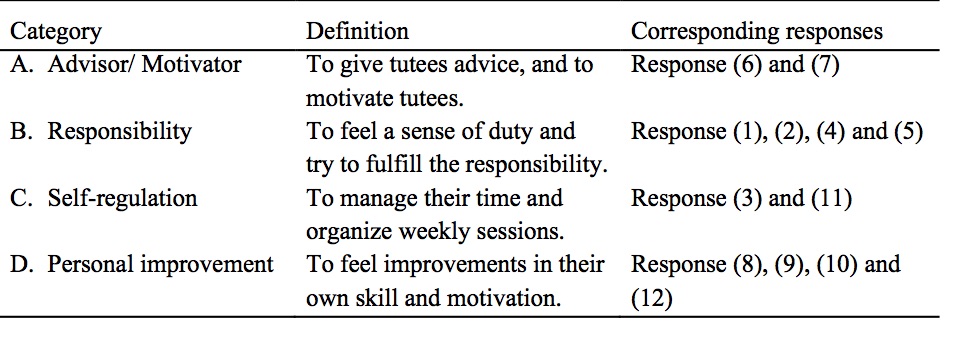

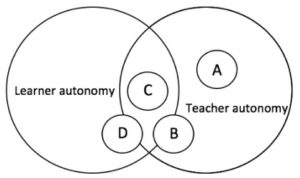

This research paid close attention to tutors’ perspectives and analyzed the data collected by means of semi-structured interview. According to the data and analyses shown above, four categories were formulated as shown in Table 2, which lists these as components of LTA. The table describes how those findings are transformed into the following four categories: Advisor/ Motivator, Responsibility, Self-regulation, and Personal improvement. In addition, those implications are transformed into the model below (Figure 1) and the location of those four constituents are visualized.

Table 2. Components of Language Tutor Autonomy

Figure 1. A model of Language Tutor Autonomy and the location of its constituents

Category A literally indicates that tutors play a role as motivators and advisors. As seen in responses (6) and (7), it can be said tutors inspire tutees by sharing their experiences. Therefore, this first category has a strong sense of teacher autonomy.

Category B is the disposition of tutors to feel a sense of responsibility and try to conduct better sessions, so that tutees will be satisfied. In addition, tutors prepare materials or explanations in advance, and this fact may imply that the preparation positively influences their self-learning. Considering these implications, tutors’ sense of responsibility has a relation to both teacher and learner autonomy as illustrated in Figure 1.

Additionally, tutors’ self-regulation (i.e., Category C) is interesting because it can be seen as autonomy located in between teacher and learner autonomy. Tutors plan, choose materials and prepare for the next session. These actions are done to teach, but simultaneously, they are normally done to learn. It might be possible to say that their preparation to teach turns out to be autonomous learning in action. Therefore, it would be fair to place category C in the middle of teacher and learner autonomy, and furthermore, this could be considered to be the core of LTA.

In the relation to teacher autonomy, it is necessary to note here that tutors are allowed a certain amount of “freedom”, which is an important constituent of teacher autonomy (Little, 1995). They are not instructed to employ any teaching method or style in the session. Moreover, they are allowed to use audio materials and many textbooks not only for TOEIC, TOEFL but also for English learning in general such as grammar and vocabulary. Therefore, methods or resources are determined by tutors. If this freedom was not allowed, peer tutoring would constitute a much weaker version of autonomy, and the aforementioned self-directed actions may not have taken place.

Finally, tutors showed their attempts to improve their own English skill and motivate themselves (category D). Though especially the effort of understanding grammar or deepening their knowledge is initially made for tutees, the learning truly occurred. In addition, tutors recognized what they needed to learn by themselves, and this is certainly the ideal attitude of the autonomous learner.

Conclusion

This research was undertaken to formulate a framework of LTA which is summarized in Table 2. In addition, based on the analysis of collected data, this research suggested a model of LTA (Figure 1) that may enable us to visually understand LTA and its constituent parts. This research discovered that tutors foster their language learning in the process of providing explicit knowledge, and simultaneously, the responsibility in teaching and supporting drives them to do so. As a conclusion, LTA could be defined as the capacity of tutors to enhance their language learning while fulfilling responsibilities in tutoring.

As an implication of this research, it is possible to say that tutoring can happen anywhere and anyone can be a tutor. For example, when a senior student teaches English to a younger student, such a situation can be called tutoring. Although there is no organizational support or instruction, the senior student certainly could learn something. This implication could lead to cooperative and interdependent learning in that this spontaneous learning approach has a potential to take place among learners. Moreover, though this research caters to learning outside the classroom, a possible implication in classroom contexts would be that teachers could enrich communication in the classroom by letting students talk to each other and ask “Why?” (rather than “Do you understand?”), so that students can learn more by making explicit their shallow understanding of what they think they know.

This research was conducted at a private university in Japan. However, there are more universities that organize peer tutoring programs, and therefore, it would be useful to explore other programs in other universities to confirm whether or not the findings of this research are valid in other contexts. In addition, the study would have been more interesting if it had paid attention to tutors’ individual differences such as their motivation and professional goals. For example, if there are two tutors who have different motivations; one who is doing to earn extra income and the other who is doing it to gain teaching practice, there could potentially be differences in their commitment. Therefore, a more specific focus might be necessary for further research, and at the same time, it would make the study more interesting.

Notes on the contributor

Tomoya Shirakawa is an undergraduate student at Kanda University of International Studies. He has experience working as a tutor at his university for one year. He is interested in pursuing graduate studies in English language education. His interests include autonomy and second language acquisition.

References

Benson, P. (2007). Autonomy in language teaching and learning. Language Teaching. 40, pp. 21-40. doi: 10.1017/ S0261444806003958

Benson, P. (2011). Language Learning and Teaching Beyond the Classroom: An Introduction to the Field. In. P. Benson & H. Reinders (Eds.), Beyond the language classroom (pp. 7-16). Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Benson, P. (2017). Language learning beyond the classroom: Access all areas. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 135-146. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/jun2017/benson/

Little, D. (1995). Learning as dialogue: The dependence of learner autonomy on teacher autonomy. System, 23(2), 175-181. doi:10.1016/0346-251x (95)00006-6

Mynard, J., & Almarzouqi, I. (2006). Investigating peer tutoring. ELT Journal, 60(1), pp. 13-22. doi:10.1093/elt/cci077.

Peräkyla, A. & Ruusuvuori, J. (2011). Analyzing talk and text. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. Fourth Edition, Sage, London, UK pp. 529-524. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10138/29485

Ruegg, R., Sudo, T., Takeuchi, H., & Sato, Y. (2017). Peer tutoring: Active and collaborative learning in practice. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(3), 255-267. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep2017/ruegg_et_al/

Smith, R. (n.d.). Teacher education for teacher-learner autonomy. Centre for English Language Teacher Education (DELTE), University of Warwick Retrieved from http://homepages.warwick.ac.uk/~elsdr/Teacher_autonomy.pdf

Topping, K. J. (2005). Trends in peer learning. Educational Psychology, 25(6), 631-645. doi:10.1080/01443410500345172

Tomoya (if I may),

It is always interesting to read about other Japanese universities and their tutoring centers, especially since there is so much more to learn about how peer tutoring can be used in the Japanese university context. Furthermore, the focus on the language learning side of tutor autonomy, specifically in the field of TESOL, was also quite intriguing. You’ve raised some very interesting issues in this article.

I felt that your thesis was somewhat vague, and was left asking myself what the connection was between tutors/tutees and teacher autonomy in the literature review. Perhaps by explaining the differences between tutors and teachers, you would be able to clarify the connection you are trying to make. In regards to your thesis, I feel that it is in your conclusion “LTA could be defined as the capacity of tutors to enhance their language learning while fulfilling responsibilities in tutoring” – something similar could be mentioned closer to the beginning of your article. You could also dig deeper into the area of non-native English speaking tutors as well and see if you could find out how much their language proficiency improved (this was something I always wanted to do at AIU, but never got the chance).

Once again, this was a very enjoyable read and you should be quite proud of your work!

All the best,

Hina Takeuchi