Christopher Arnott, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan.

Neil Curry, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan.

Phoebe Lyon, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan.

Jo Mynard, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan.

Arnott, C., Curry, N., Lyon, P., & Mynard, J. (2019). Measuring the effectiveness of time management training in EFL classes: Phase 1 of a mixed methods study. Relay Journal, 2(1), 86-101. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020113

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

In this paper, the authors describe an intervention and research project that aims to understand how students manage their time, and also to investigate the impact of integrating time management training activities into a general English language proficiency course. The results will be shared in subsequent papers, but the rationale, background and methods are presented here in order to document the initial stages of the project. Students in three university English classes in a Japanese university participated in the time management training activities and completed reflection sheets which will later be analysed qualitatively. In addition, participants completed a pre- and post- intervention multiple choice questionnaires about time management. A control group comprising three similar classes also completed the pre- and post- intervention questionnaire, but did not participate in the time management training activities or reflection tasks.

Keywords: time management; self-directed learning; learner autonomy

Time management skills are considered to be a crucial component of self-directed learning. Most students have very busy schedules and competing priorities; for example, in our context, as well as taking a variety of different classes, students complete tasks with multiple conflicting deadlines. In addition to assignments and homework, students have club activities which often require several multiple-hour meetings per week, part-time jobs, commutes, the need or desire for self-study, and of course social commitments and the need to rest and relax. Students with better time management skills are more likely to achieve academic success (Liu, Rijmen, MacCann, & Roberts, 2009). Without at least a rudimentary management of their daily activities, many students are apt to find that they are unable to meet deadlines, cannot complete assignments to a very high degree of quality, and can suffer from a lack of rest with its attendant problems. Learning how to control one’s own schedule is vital not only during university, but also when subsequently entering the workforce. The purpose of this paper is to give a brief summary of the initial portion of a research project designed to understand how students managed their time, and gather the perceptions of the teachers and learners on a series of time management tasks integrated into a university English class. A more thorough analysis of the data will follow in subsequent papers, but the authors intend to document the process in phases in order to be systematic and transparent.

Background and Context

This study takes place at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS), a small university specialising in foreign languages located near Tokyo in Japan. Currently, the choice of whether or not to include the teaching of time management skills at KUIS is usually left up to the individual classroom teachers. However, the Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) provides optional self-directed learning (SDL) courses which include a focus on time management. These SDL courses include materials covering techniques for helping students find time for activities relating to their personal learning goals. These include prioritizing tasks, tasks related to effective use of ‘bits’ and ‘blocks’ of time, (i.e. short- and longer periods); and a related activity helping students to effectively plan their week using a planner to determine what free time they normally have. Finally, there is also an activity related to helping students to determine what study activities can be completed in the available time. Other activities that will be introduced in the near future include dealing with distractions and making ‘to-do’ lists. Unfortunately, although time management training was identified as a student need during previous research at the institution (Takahashi et al., 2013) and the curriculum activities were perceived to be useful by students taking the courses (Thornton & Hasegawa, 2014), not all students are able to take these SDL courses for logistical reasons. As teachers and learners often seek help from learning advisors with managing their time and managing busy schedules, the authors embarked on this project which involved creating, piloting, and researching the effectiveness of incorporating the teaching of these skills into classroom activities. The eventual aim is to ensure that the student body as a whole receives support with managing their time.

Researching Time Management

Time management is generally considered an important aspect of managing one’s learning processes (Henry, 2017). Previous findings by researchers in other contexts have shown that (1) students need to acquire time management skills (Henry, 2017), (2) time management is positively linked to performance in academic settings (Liu et al., 2009; Babayi Nadinloyi, Hajloo, Garamaleki, & Sadeghi, 2013), and (3) that time management skills can be effectively taught (Babayi Nadinloyi et al., 2013). Although anecdotally, the researchers have observed positive effects on learning when time management activities have been intentionally taught to students, this has never been researched in the this context.

There are several ways that the research could be approached, but previous researchers investigating classroom interventions have tended to use quantitative measures with a quasi-experimental design using a pre- and post- survey (e.g. Babayi Nadinloyi, et al., 2013; Britton & Tesser, 1991). For the present project, the researchers decided to replicate a quantitative approach as one way to evaluate the effectiveness of the training. In addition, as the authors were interested in gathering perceptions of the pilot activities from teachers and students, qualitative methods were also used.

Research Questions

To guide this portion of the research, the following research questions were generated:

Teacher perceptions

- What do the teachers notice about the ways in which students approach the time management tasks?

- What do teachers notice about the challenges students had completing the time management tasks?

- How did these tasks add to teachers’ understanding of the ways in which their students managed their time?

Learner perceptions

- What are learners’ perceptions of the usefulness of the time management tasks?

- What difficulties did students experience in time management?

- How likely are students to use time management activities in the future (for their studies and also other aspects of their lives)?

Evaluating the effectiveness of time management training

- Did the questionnaire indicate that students’ awareness of time management strategies increased?

- Did the student reflections indicate that students’ awareness of time management strategies increased?

Participants

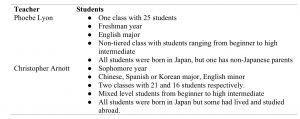

Two of the researchers were also the two teachers collecting data in their classes. The student participants were chosen for convenience reasons. Below is a table summarizing the teachers and information about their student participants.

Table 1. Teacher and Student Information

Researchers

Neil Curry and Jo Mynard are researchers in this project. They are also learning advisors and were able to assist with designing and planning the time management and reflection activities, and also with the research process based on their previous experience. Phoebe Lyon and Christopher Arnott, in addition to teaching the participant students, were also researchers in this project.

Research Methods

Qualitative methods: Classroom activities and student reflections

Students in three classes received approximately three hours of instruction (One 90-minute session plus homework, and three 20-minute sessions) and awareness raising over the course of the semester related to time management issues of their project work during a one semester (15-week) period. Both teachers of these classes administered a reflection activity sheet related to their experience (Appendix A) three times. A qualitative analysis of these handwritten reflections is currently in progress and will be reported in a subsequent publication. The qualitative analysis will involve coding and interpreting learners’ reflections in order to explore learners perceptions of the tasks and whether they helped to raise awareness of time management skills.

Phoebe’s class. Prior to receiving their first assignment for the semester, students in all three classes were asked to complete a worksheet on time management (Appendix A). They were asked to rank upcoming important homework assignments and allocate time estimates to each of them. The students were also asked to decide which tasks could be completed in ‘bits’ versus ‘blocks’. The final task was to fill in a calendar with their upcoming weekly schedule, including classes, part-time jobs, commuting time, eating time, resting/ sleeping time, club activity time and anything else that might be relevant to them. Once they could see their ‘free time’, they were asked to compare with their group members to see when they could potentially work on their project together outside of class time. For homework, they were asked to complete the reflection at the end of that first worksheet.

Once the students began working on their assignments, they were asked to list and rank the important tasks needed to complete the project, decide what could be done alone versus with their group members, and whether they needed a ‘bit’ or a ‘block’ to complete the tasks. This was repeated toward the end of the assignment. Once the assignment was complete, students were asked to write a reflection on their experience (Appendix B).

Upon starting the second assignment for the semester, a similar intervention to the one described above was repeated, once more followed by a written reflection after the assignment was complete. For the third assignment of the semester, no interventions or reminders were given in order to see what students accomplished without any prompting. The second and third reflection sheets were modified each time from the original reflection sheet (also in Appendix B).

Christopher’s classes. The procedure for the first unit was similar to Phoebe’s classes except that the assignments were individual so there was no need for comparing and matching schedules. For the second assignment, students were reminded of the activities they had undertaken before (dividing activities into ‘bits’ and ‘blocks’ and ranking importance of tasks), but not given specific class time to recreate them though they were given the same blank schedules once more to fill out with their team members in class. For the third assignment, as above, no interventions or reminders were given at all.

Teacher reflections. Both classroom teachers kept a diary, reflecting on their perceptions of how students completed the initial time management worksheet and the subsequent reflection activities, as well as their perceptions on how students were managing their time. These reflective diary entries will be coded and analysed to look for themes that emerge. Follow up interviews conducted by the two other researcher may also be conducted if more depth is needed.

Quantitative methods

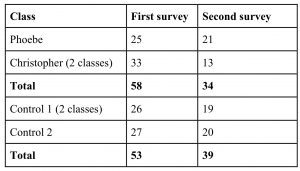

In addition to the qualitative instruments, an adapted version of Britton and Tesser’s (1991) questionnaire (Appendix C) was administered to the three classes at the beginning and the end of the semester (i.e. as a pre-test and post-test) via SurveyMonkey. The instrument was translated into Japanese by a research assistant and was piloted and refined before being administered to the participants of the study. The purpose of the questionnaire is to measure whether there have been any changes in students’ awareness and management of time related to their academic work. The questionnaire was also administered to four similar classes who were not receiving any time management instruction. The control groups were taught by different instructors who were following the same basic curriculum. The questionnaire was administered during class time and took students five minutes or less to complete. The teachers of all seven classes taking the test explained to the students that the test was optional. A quantitative analysis of the pre-test / post-test will investigate differences between two groups in terms of whether awareness of time management increased.

Table 2. Summary of Questionnaire Response Numbers

Ethical Considerations

This research followed the ethical guidelines provided by the institution and received appropriate approval before data collection commenced. The student participants were informed of the purpose of research in class by their teacher, and were asked to read the plain language statement (in Japanese) and sign a consent form before continuing. Students could opt out of taking the surveys without penalty and could choose to exclude their written reflections from the data set. The survey is anonymous and unobtrusive. No remuneration was given to students as the research took place in class time.

Limitations

As with any research, factors related to individual differences, teacher, and willingness to participate may affect the results and this will be acknowledged. The mixed methods approach and data triangulation will attempt to improve reliability and the researchers are hoping to make some general observations from qualitative and quantitative data that indicate whether the activities have been effective.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank colleagues and students for their assistance with this project: James Owens for his helpful comments on the original research proposal; Jianwen Chen and Amber Barr for their assistance with the data collection; Arthur Nguyen for his help with statistical analysis; Satomi Wolfenden for assisting with translating and piloting the quantitative instrument; and to all of the students who participated in the study.

Notes on the Contributors

Christopher Arnott is a lecturer in the English Language Institute (ELI) at Kanda University of International Studies. His research interests include student motivation, teacher motivation and learner autonomy.

Neil Curry is a principal learning advisor in the Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) at Kanda University of International Studies. His research interests include self-directed learning, learner autonomy, and language anxiety.

Phoebe Lyon is a principal lecturer in the English Language Institute (ELI) at Kanda University of International Studies. Her research interests include learner autonomy, student motivation, curriculum design and assessment.

Jo Mynard is a professor, director of the Self-Access Learning Centre (SALC) and Director of the Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education (RILAE) at Kanda University of International Studies. Her research interests include learner autonomy and the psychology of language learning.

References

Britton, B. K., & Tesser, A. (1991). Effects of time-management practices on college grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(3), 405–410. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.83.3.405

Hasegawa, Y., & Thornton, K. (2014). Examining the perspectives of students on a self-directed learning module. In J. Mynard & C. Ludwig (Eds.), Autonomy in language learning: Tools, tasks and environments. Faversham, UK: IATEFL.

Henry, K. (2017). Academic performance and the practice of self-directed learning: The adult student perspective. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 41(1), 44-59. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2015.1062849

Liu, O.L., Rijmen, F., MacCann, C., & Roberts, R. (2009). The assessment of time management skills in middle-school students. Personality and Individual Differences. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.02.018

Nadinloyi, K. B., Hajloo, N., Garamaleki, N. S., & Sadeghi, H. (2013). The study efficacy of time management training on increased academic time management of students. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 84(9), 134-138. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.523

Takahashi, K., Mynard, J., Noguchi, J., Sakai, A., Thornton, K., & Yamaguchi, A. (2013). Needs analysis: Investigating students’ self-directed learning needs using multiple data sources. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(3), 208-218. Retrieved from http://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep13/takahashi_et_al