Neil Curry, Kanda University of International Studies, Chiba, Japan

Curry, N. (2019). A new direction: Developing a curriculum for self-directed learning skills. Relay Journal, 2(1), 75-85. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020112

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

This paper describes the context and rationale of a project to integrate self-directed learning activities into the regular classes in an English language teaching curriculum. It is hoped that in the near future a number of activities will be designed and piloted by teachers and learning advisors together which will fit into existing classroom lessons, leading to students learning these skills in an ‘organic’ way, and also lead to closer cooperation between the different university departments involved.

The purpose of this paper is to introduce the current curriculum development project underway at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS), a mid-sized privately-owned university in Japan specializing in language tuition. One of the university’s aims is to promote and develop learner autonomy among the student body, and instrumental to that is the role of the Self-Access Learning Centre (SALC), a purpose-built facility designed to provide students with opportunities and resources to learn and practice language outside the classroom. Learning Advisors (LAs) are present to offer help to students looking for guidance in their learning choices.

The SALC is also one of the departments of the university, and has the responsibility of delivering a curriculum designed to introduce and develop self-directed learning (SDL) skills to the students. SDL skills are those needed to achieve the ability to make choices and manage activities related to the achievement of personal learning goals. This current curriculum has been shown to function very effectively (Curry, Mynard, Noguchi, & Watkins, 2017), but it has reached a point where its present format needs further development in order to better serve the needs of students and faculty. This paper will outline the rationale and goals for the SALC curriculum project, and describe some of its current activities.

Student context and learner autonomy

As stated above, the university recognizes the need to encourage autonomous language learning with the students. First-year students are often the product of a school system which generally does not provide much opportunity for developing communicative language in classrooms, and which mainly focusses on teaching language (almost exclusively English) as an academic subject with the intended outcome of students being able to pass tests, and is also delivered in the traditional classroom format with the teacher as expert and the student as a largely passive recipient. As a result many new students at KUIS can have a narrow view of how language is learned, and are unaware or do not know how to make or take advantage of new and varied learning opportunities. Henceforth we believe that some training in SDL skills is hugely beneficial to them, and the SALC does this in the form of classroom-based taught courses and self-study ‘modular’ courses based on outcomes established by the previous curriculum evaluation project (Takahashi et al., 2013), which offer instruction in the following:

- Goal setting

- Choosing appropriate learning strategies

- Choosing appropriate learning resources

- Time management

- Dealing with motivation and confidence issues

- Making study plans

- Implementing a study plan

- Evaluating learning gain

By the end of the courses, students should be able to demonstrate that they have been able to understand and use the skills through continual self-reflection on their decisions and activities. The courses are taught by LAs who help to guide students through a written and spoken dialogue which has the effect of developing an ‘internal dialogue’ about how and why they arrive at their choices concerning their learning (Mynard & Carson, 2012). In practice this means that students will gain awareness of their learning processes, understanding in what ways they learn most successfully and what their motivational factors are and how to utilize them. Overall, they should reach some understanding of who they are as a learner.

Rationale for curriculum development

The current SALC curriculum is the product of an extensive evaluation project conducted by SALC LAs from 2012 – 2013, utilizing the language curriculum framework of Nation & Macalister (2010). This was conducted in conjunction with curriculum renewal underway in the English Language Institute (ELI), the department responsible for delivering English language instruction, and with whom the SALC LAs work particularly closely. There was also a desire for a more organized review of the SALC curriculum as opposed to the more ad hoc way in which the courses were usually reviewed (Thornton, 2013). The first step undertaken was an environment analysis, to investigate the needs of the students and to develop a set of learning outcomes by which the curriculum could be evaluated (Thornton, 2013). Subsequently, the next steps included a needs analysis of the SDL skills thought necessary to possess by students, teachers and learning advisors (Takahashi et al., 2013), after which a set of foundational principles for evaluating the strengths, weaknesses and efficacy of the current (as then) curriculum was formalized (Lammons, 2013). The re-designed curriculum was then piloted with students and subsequently analysed and evaluated, with the main conclusion being that an implementation stage for the students to try out their learning plans was needed (Watkins, Curry, & Mynard, 2014).

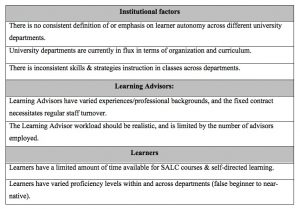

The environment analysis described by Thornton (2013) is particularly relevant for the current project, as the findings, specifically the environmental constraints, are just as relevant today as they were in 2012. The table below describes these factors:

Table 1. Important Constraints of our Environment

(Thornton 2013, p.150)

As of the date of writing, it is accurate to say that the same constraints are still present, with the following of particular concern to the present study;

- Although we have an official definition for learner autonomy, there is not consistent emphasis on autonomous learning throughout university departments

- Inconsistent strategy & skill instruction

- Limited number of advisors and workload considerations

- Limited amounts of time available for students to take SALC courses

For the first, dealing with the emphasis on autonomy, the most salient point is that the SALC is heavily concerned with the promotion of autonomy, but it is probably safe to say that for other departments, different concerns might be a priority, despite regular updates and meetings with other departments to advise them on current SALC activities. In practical terms, this may also mean that students may only receive encouragement and guidance to seek autonomy if they engage with SALC courses or LAs.

Regarding SDL skill instruction, students do receive some instruction in their classes, but the scope of this is often dependent upon the individual teacher, and there is no institutional guidelines or strategies for such instruction, so their exposure to these skills is highly varied. Currently there are eleven LAs, the largest number since the position was established, but for them to be able to provide classes for all freshman students, their numbers would have to be quadrupled; an unrealistic position budget-wise. In addition, Thornton (2013) comments on the average study and life commitments that students have, and these have not changed since. Therefore, time for taking SALC courses is still limited.

In consideration of these environmental constraints and the conclusions of the previous SALC curriculum project, the current project has decided to address the fundamental problem directly; how do we instruct the student body in SDL skills in a consistent and efficient way, accounting for the limitations imposed by the current situation? One practical answer is to integrate the SALC curriculum into the ELI curriculum, so that instruction in SDL skills becomes a regular feature of Freshman and Sophomore English classes. This can ensure that all students become aware of SDL skills in a consistent way in their regular lessons, and classroom delivery means that the small number of LAs will not be an impediment.

Working with teachers

The previous curriculum project described the piloting and evaluation of redesigned SDL in-class instruction activities, which demonstrated that students were able to successfully learn and practice the SDL skills taught, and when surveyed were mostly positive as to their usefulness for students’ own learning (Watkins, Curry & Mynard, 2014). Despite this success, the pilot activities were never adopted by the ELI management team, despite the initial research showing support for SDL instruction among the teaching staff.

However, as of 2017 a new ELI management structure is in place, and the plan of the SALC to integrate our curriculum into ELI English classes has been met with enthusiasm. To lend support to our intentions and to gauge the attitudes and practices of ELI teachers, a simple online survey was conducted in 2017 to which a total of 18 teachers responded, about one-third of the total ELI teaching staff. This showed unanimous support for instructing students in SDL skills, and also showed that a majority actively taught a number of these skills at some point during the academic year.

Knowing that the support for promoting autonomous learning is present, the decision was made to take a different approach to the previous 2012-13 project, namely to include individual teachers in the creation and piloting of SDL skills in their classrooms. The previous project taught the skills explicitly, and students related them directly to their out of class learning. We currently believe that a more ‘organic’ approach may be more successful; introducing the skills to students through incorporating them into existing class activities and assignments, so that they appear to become a more ‘natural’ way of thinking about individual study, with the students encouraged by reflective activities to connect the SDL knowledge to other learning goals. The ultimate goal is to make the idea of learner autonomy and the practice of SDL skills an integral part of the teaching philosophy at KUIS, where it is seen as a normal and natural part of the learning and teaching experience by students and teachers alike. By cooperating directly with teachers in designing and trialing the SDL activities, the project will not only help to create a closer working relationship between the two departments, but also give teachers a sense of ‘owning’ the activities, and not having them imposed from an outside body, which may have sometimes been the case in the past when points for SALC modules taken by students were added to their classroom grades.

As a result, an appeal was made to ELI teachers and SALC learning advisors to join the curriculum project and work together on developing classroom activities for SDL skills. Currently, there are four sub-projects underway utilizing freshman English classes, which will be outlined below.

Current activities

- Time management

This group has been introducing different time management techniques and will be evaluating their effectiveness based on student feedback, examining what difficulties they face and if awareness of time management strategies increases. We will also explore teachers’ own perceptions of how students are using their time. (Arnott, Curry, Lyon, & Mynard, 2019)

- Choosing resources

This sub-project focusses on Foundational Literacies classes, where students work on their reading and writing skills. The SDL activities encourage students to link their resource choices to specific learning goals, and reflect on the suitability of their choices. It is hoped that they will be able to make more effective decisions regarding choosing resources that match their own learning styles and needs, thus reflecting on their own personalities as learners. By monitoring student reflections, teachers and LAs will be able to identify points at where students may need extra help, and offer interventions. This will also provide a means by which we can determine the likely amount of time an LA might need to interact with a class, and so help us to plan future workload priorities.

- Self-evaluation

Here students are conducting regular reflective activities in order to determine their own progress in their speaking abilities, and be able to identify factors which aid or impede improvement, and which lead them to feel more competent and comfortable with speaking English in class. We will also gauge how useful students feel such activities to be, and using different classes, experiment with whether the frequency of doing these reflections leads to any differences in the feedback from students.

- Confidence-building

Anxiety in speaking in a foreign language is a well-documented problem (Gregersen & MacIntyre, 2014; Horwitz, 1986; MacIntyre, 1994; MacIntyre, 2017), and we have found that talking in front of peers is often a facilitator, as students fear being thought badly of in the event of mistakes or misunderstandings. Therefore activities which help to alleviate these fears and can serve as a class bonding exercise are deemed to be valuable in helping to create an atmosphere in which students feel confident and can maximize their opportunities to talk.

All of the above projects have been piloting activities and will commence as official research projects from next semester. They will be described in subsequent publications.

Future directions

Next semester, as well as continuing the above sub-projects, we hope to recruit more teachers to work on further SDL activities, such as learning strategies and making learning plans. The idea of introducing the skills to Freshman classes is so that new students will be able to use these skills and develop them further throughout their university careers and beyond, as for many of them their language learning will not cease at graduation. For this reason we must ensure regular reviewing and reflection activities take place, and most importantly that students are made aware of the ways in which they can use these skills not only for class-related tasks, but also for other learning goals and even lifestyle goals which exist beyond the language classroom. Therefore all reflection tasks encourage the students to think of other situations where the skills they have practiced can be used.

The integration our SALC course content into regular English classes also poses the question of what role the SALC will continue to play in SDL skill instruction. Supporting teachers with these activities in class is an existing option, but owing to limited numbers of LAs we must carefully consider the practicalities of how much we are able to work directly with classes. We may be able to offer more taught courses for those students in their third and fourth years who are now thinking more deeply about their lives after university, and have to find ways of learning languages without the support of a learning institution. We should also try to cultivate closer links to the non-English major departments in order to attempt to introduce SDL to their classes. Therefore, another project consideration is to look at what other roles the LA is able to play in the future.

Ultimately however, we are confident that we can help to give all of our students the awareness that they themselves can be in control and command of their own learning choices, helping to produce autonomous graduates who are confident and competent as they embark onto the next stage of their lives.

Notes on the Contributor

Neil Curry is a learning advisor at Kanda University of International Studies in Chiba, Japan. His main areas of interest are self-directed learning, language anxiety and curriculum development.

References

Arnott, C., Curry, N., Lyon, P., & Mynard, J. (2019). Measuring the effectiveness of time management training in EFL classes: Phase 1 of a mixed methods study. Relay Journal, 2(1).

Curry, N., Mynard J., Noguchi, J., & Watkins, S. (2017). Evaluating a self-directed language learning course in a Japanese university. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 14(1), 17-36.

Gregersen, T., & MacIntyre, P. D. (2014). Capitalizing on learners’ individuality: From premise to practice. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125 – 132.

Lammons, E. (2013). Principles: Establishing the foundation for a self-access curriculum. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(4), 353-366. Retrieved from sisaljournal.org/archives/dec13/lammons/

MacIntyre, P. (2017). An overview of language anxiety research and trends in its development. In C. Gkonou, M. Daubney & J-M Dewaele (Eds.) New insights into language anxiety: Theory, research and practical implications. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Mynard, J., & Carson, L. (2012) (Eds.). Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context. Harlow, UK: Pearson.

Nation, I. S. P., & Macalister, J. (2010). Language curriculum design. London, UK: Routledge.

Takahashi, K., Mynard, J., Noguchi, J., Sakai, A., Thornton, K., & Yamaguchi, A. (2013). Needs analysis: Investigating students’ self-directed learning needs using multiple data sources. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(3), 208-218. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/sep13/takahashi_et_al

Thornton, K. (2013). A framework for curriculum reform: Re-designing a curriculum for self-directed language learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(2), 142-153. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/june13/thornton/

Watkins, S., Curry, N., & Mynard, J. (2014). Piloting and evaluating a redesigned self-directed learning curriculum. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 5(1), 58-78. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/mar14/watkins_curry_mynard/

Dear Neil,

I was impressed to learn the self-directed learning-oriented curriculum you have been working on and how the projects have been carried over by many advisors in the past (Curry et al., 2017; Lammons, 2013; Takahashi et al, 2013; Thornton, 2013; Watkins, Curry & Mynard, 2014). It is great that the past studies provided you with more ideas to enrich your project. The project you are currently working on which is to integrate the SALC curriculum into the ELI curriculum could be one of the best ways to provide an opportunity for all Freshman and Sophomore students to become aware of SDL skills.

Advisors working at the SALC could be appropriate to implement such curriculums. However, the number of advisors is limited to deliver classes as you have pointed out. The idea of having teachers and advisors work together to develop classes and activities is a wonderful movement!

The four sub-projects you mentioned are focusing on time management, choosing resources, self-evaluation, and confidence building. I think these are nice choices as they are all essential skills to promote autonomy. As the activities look well designed, it would be great if you could share some examples (lesson plan, worksheets, teaching materials, etc.) so that we can learn more from your project.

Especially, I was impressed with your idea about giving teachers a ‘sense of owning the activities’ — it matches the concept of teacher autonomy. Also, as you mentioned, it is important to provide teachers with education to facilitate self-directed classrooms. Reinders & Balcikanli (2012) mention that teacher autonomy and learner autonomy are closely linked and teachers need sufficient knowledge and guidance to develop the skills to be able to foster learner autonomy in their own classrooms.

What kind of teacher education have you provided so far or planning to provide in the future? One of the ways is to facilitate ‘collaborative reflection’ among the teachers who are involved in this project. Collaboration with colleagues helps teachers to become successfully reflective and also enhances confidence in their professional development (Chase, Brownstein, & Distad, 2001; Day, 1993). Through collaborative reflection, teachers are likely to examine their teaching practices, learn more about themselves, gain knowledge, and thus be able to transform their existing values (Glazer, Abbott, & Harris, 2000, 2004; Mede, 2010). Conducting collaborative reflection or keeping reflective journals and focusing on how teachers’ perception will change by going through this process is also an interesting research topic. You can conduct a variety of research in this project!

In the near future, I agree that advisors would have different responsibilities in the SALC. One of the roles could be providing such teacher training to promote the self-directed learning-oriented curriculum, and your project provides the foundation in this area!

References

Day, C. (1993). Reflection: a necessary but not sufficient condition for professional development, British Educational Research Journal, 19(1), 83–94. doi:10.1080/0141192930190107

Glazer, C., Abbott, L., & Harris, J. (2004). A teacher-developed process for collaborative professional reflection. Reflective Practice, 5, 33-46. doi:10.1080/1462394032000169947

Reinders, H., & Balcikanli, C. (2011). Learning to foster autonomy: The role of teacher education materials Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 2(1), 15- 25. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/mar11/reinders_balcikanli/