(Previously titled: How Successful and Less Successful Japanese Learners of English Deal With Speaking Anxiety)

Hung Nguyen-Xuan, Kanazawa Institute of Technology, Nonoichi, Japan

Nguyen-Xuan, H. (2019). An exploratory case study of English speaking anxiety faced by successful and less successful Japanese learners. Relay Journal, 2(1), 158-169. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020120

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

This article addresses the English speaking anxiety faced by successful and less successful Japanese learners of English. Two Japanese EFL students (one successful and one less successful) agreed to participate in the research. A survey and a semi-structured interview were used to gather the details of these two learners’ English learning experiences and frequency of dealing with English speaking anxiety. Results indicate that both learners felt speaking anxiety, but the less successful learner felt anxiety more frequently than the successful one. The successful learner also appeared to show high motivation and willingness to speak English, whereas the less successful one felt shy or tended to have fear of speaking English. The study is expected to provide some useful insights for further research of EFL students’ speaking anxiety.

Keywords: Speaking anxiety, successful learner, less successful learner, speaking situations

Speaking can cause anxiety for all second language (L2) learners, whether successful or less successful learners, for many reasons, such as lack of vocabulary, low grammar proficiency or fear of making mistakes (Thornbury, 2005). Language anxiety “has consistently attracted attention in L2 studies” (Dörnyei & Ryan, 2015, p. 175) and can affect L2 learners’ performance (Döynei & Ryan, 2015; Gardner & MacIntyre, 1992) or achievements (Khattak, Jamshed, Ahmad, & Baig, 2011).

Research into language anxiety has confirmed its impact on L2 learners, but has not yet compared how successful learners (SLs) and less successful learners (LSLs) deal with language anxiety in L2 speaking performance differently. This exploratory case study, therefore, aims to examine the speaking anxiety faced by SLs and LSLs in their English learning.

Literature Review

Successful and less successful EFL learners

Rubin (1975) reports that successful language learners are good guessers, usually strongly motivated to communicate, not afraid of making mistakes or being foolish in communication, attending to both form and meaning, eager to use the language wherever possible, and in control of their speech.

Gan, Humphreys, and Hamp-Lyons (2004) further claim that SLs use greater learning strategies more appropriately, whereas unsuccessful learners use limited learning strategies inappropriately. As mentioned by Philp (2017), the success of L2 learners can be contributed by their willingness to communicate.

Language anxiety

MacIntyre (1999, cited in Dörnyei & Ryan, 2015) views the construct of language anxiety “as the worry and negative emotional reaction aroused when learning or using a second language” (p. 27). Some of the most distinguishing characteristics of language anxiety have been highlighted in Dörnyei & Ryan (2015), including: anxiety as a symptom of cognitive deficit, anxiety and multilingualism, anxiety and personality, anxiety and idiodynamic variation, and positive aspects of anxiety.

Language anxiety occurs in communication or when taking a test or when being evaluated negatively (Horwitz, Horwitz & Cope, 1986). These researchers developed ‘the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale’ (FLCAS) to measure anxiety levels. A high scorer on this scale indicates his or her language anxiety.

Speaking anxiety in L2 learning

Speaking anxiety occurs when learners lack self-confidence in expressing their opinions (Sadiq, 2017) or when teachers ask questions in the class (Williams & Andrade, 2008). L2 learners experience language anxiety in different ways, such as: fear to speak, fear to misunderstand others and to be misunderstood, and fear to be laughed at, which can cause negative feelings (Dörnyei & Ryan, 2015; Sadiq, 2017).

A study by Zhiping and Paramasivam (2013) shows that Nigerian students had low English speaking anxiety, whereas Iranians and Algerians suffered high speaking anxiety in an international class in Malaysia due to their negative or unfavorable evaluation and fear of communication. Additionally, the results of Indrianty’s (2016) study unveil: a) the traits and situational anxiety faced by Indonesian students; b) sources of students’ speaking anxiety, including test taking and fear of communication and negative evaluation; and c) lack of vocabulary and preparation. In this exploratory study, Japanese EFL students’ speaking anxiety will be examined in relation to these findings.

Speaking anxiety of Japanese EFL learners has also gained increased attention in recent years. The skill of speaking for most Japanese EFL learners is challenging because they are usually reluctant or shy (Cutrone, 2009; Harumi, 2010). According to Cutrone (2009), this issue is caused by the learners’ inexperience and cultural inhibitions when they deal with Western teaching methods, interactional areas, and teachers’ attitudes, which results in language anxiety (Townsend & Danling, 1998). Suzuki’s (2013) study adapting Horwitz et al.’s (1986) FLCAS identifies Japanese EFL students’ dynamic feelings of speaking anxiety during their course due to their lack of speaking confidence, fear of peers’ negative evaluation, and communication apprehension with the teacher. Similarly, Kudo, Harada, Eguchi and Suzuki’s (2017) study confirms Japanese students’ strong anxiety that happens when they do not have confidence in English speaking and when they receive unfavorable evaluations from others.

In conclusion, prior research has indicated L2 learners’ speaking anxiety in language learning (Indrianty, 2016; Kudo et al., 2017; Suzuki, 2013; Zhiping & Paramasivam, 2013). However, there is a gap in the literature about how successful and less successful English learners’ speaking anxiety differs. The current study attempts to further contribute to the existing research by examining the speaking anxiety of both SLs and LSLs in the EFL context in Japan.

Research Questions

Three research questions emerged:

- What situations cause successful and less successful Japanese learners of English to have English speaking anxiety?

- How frequently do they face the language anxiety in English speaking performance?

- How do they react to the speaking anxiety in those situations?

Research context and methodology

The research was conducted with two EFL Japanese students (one successful and one less successful) on October 30, 2018 at an engineering university in Japan. The participant selection was based on the researcher’s perception and observation in their class, which was taught by the researcher. The successful student always did his assignments in English to the required standard and was the most active student in the class, especially in responding to teacher’s questions or asking questions in English. The less successful student appeared to be very shy. She never asked questions in English in the class, sometimes struggled to complete the assignments or refused to answer questions from the teacher. Both learners agreed to participate in the research after the purpose of the research was clearly explained to them. Although the sample of this study was small, what they provided could be useful for adding to current knowledge about speaking anxiety (Halbach, 2000).

This study applied a survey questionnaire and a semi-structured interview (see Appendix). The questionnaire development was based on the contents of Horwitz et al.’s (1986) FLCAS items with some adjustments to focus on speaking anxiety and the use of a ‘frequency’ scale. The questionnaire consisted of two parts. Part one aimed to gather information about the participants’ personal backgrounds. Part two asked participants to rate their frequency of speaking anxiety in each situation (11 situations) on a five-scaled Likert format from 1 to 5 (1 being ‘never’, 2 for ‘rarely’, 3 for ‘sometimes’, 4 for ‘very often’, and 5 for ‘always’). The interview was intended to further elicit participants’ responses in dealing with those speaking anxiety situations in Part two of the questionnaire.

The participants took the interview in turns. The successful learner was interviewed first, then he helped the less successful learner with some translations during her interview. The researcher took notes of their responses because the learners did not feel comfortable having their voices recorded. Most of student B’s responses were in Japanese and later translated into English by the researcher with the help of student A. After each interview was finished, the researcher confirmed the notes with the participants to make sure they were accurate.

Data Analysis and Discussion

Data collected from the questionnaire and interviews were analyzed and categorized. A descriptive method was employed to compare the English learning backgrounds of the two learners and the frequency of their reactions to English speaking anxiety in different situations. To protect the participants’ identity, their names were coded as student A (successful learner) and student B (less successful learner).

Part one of the survey asked participants about their linguistic and educational backgrounds, especially regarding their majors, years of university study, English learning and English test-taking experiences, international travel experiences, and number of foreign languages they could speak. Their responses collected show that student A whose major is Aeronautics has been learning English for eight years and has also achieved a TOEIC test score of 575. His additional language experience includes a trip to Canada. Although student B, whose major is Mechanical Engineering, has been learning English for six years, she has not taken any English tests and has not yet travelled to any English speaking countries. This data indicates that student A seems to have had richer English learning, English test taking, and international travel experiences than student B. In Part two of the survey, 11 English speaking situations were examined to explore the frequency of two students’ English speaking anxiety. Table 1 depicts the 11 situations and highlights both students’ responses to each speaking situation, numbered from 1-11.

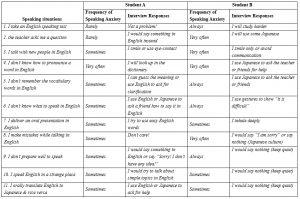

Table 1. Frequency of Speaking Anxiety and Interview Responses

Data in Table 1 show that student A reported low frequencies of facing speaking anxiety in situations 1 and 2 (“rarely”: 18%); higher frequency in situation 4 (“very often”: 0.9%); and neutral for situations 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 (“sometimes”: 72.7%). The frequency total score that the student A received is 32 (58%), which indicates a relatively neutral anxiety.

For student B, low frequencies were reported in situations 7, 10, and 11 (“sometimes”: 27%); higher in situations 1, 5, 6, and 9 (“always”: 36.3% and 2, 3, 4, and 8 (“very often”: 36.3%) respectively. Student B’s total score for the speaking anxiety frequency is 45 (82.8%). This implies student B’s higher frequency of anxiety. Surprisingly, both students “very often” felt anxious when they could not pronounce an English word (situation 4).

The results reveal the different English speaking anxieties that both students experienced in each situation. Student B reported experiencing or feeling anxiety more frequently than student A.

Table 1 also shows two candidates’ different responses to each speaking situation. Student A’s responses in most situations display this learner’s high effort in keeping or initiating the communication in English, such as in situations 3 (“I would say something in English instead”), 4 (“I can guess the meaning or use English to ask for clarification”), 6 (“I use English … to ask … how to say…”), 7 (“I try to use easy English”), 9 (“I would say something in English”), 10 (“I would try to talk about simple topics in English”), and 11 (“I use English … to ask for help”). This data and the survey responses suggest this learner’s strong “willingness to communicate” (WTC) (Dörnyei & Ryan, 2015; Philp, 2017) or high motivation to speak (Rubin, 1975) and show his low language anxiety or high self-confidence and comfort in those English speaking situations.

In contrast, student B reported to be unwilling or too shy to continue the conversation in most situations. This learner often described using Japanese or simply keeping quiet when dealing with the language anxiety. This data and the survey responses may indicate student B’s limited English learning strategies to continue the conversation (Gan, Humphreys, & Hamp-Lyons, 2004), and her high speaking anxiety, which previous research suggests may be the manifestation of her fear of speaking, her Japanese cultural inhibitions, shyness, or lack of self-confidence (Cutrone, 2009; Dörnyei & Ryan, 2015; Harumi, 2010; Sadiq, 2017; & Townsend & Danling, 1998).

Conclusions

This exploratory case study attempted to examine the speaking anxiety of both successful and less successful Japanese learners of English using a survey questionnaire and an interview. The results are as follows.

a) Research question 1: What situations cause successful and less successful Japanese learners of English to have English speaking anxiety?

The following situations are believed to have caused both students to have the English speaking anxiety:

– When they took an English speaking test.

– When the teacher asked them a question.

– When they talked with new people in English.

– When they did not know how to pronounce a word in English.

– When they did not remember the vocabulary words in English.

– When they did not know what to speak in English.

– When they delivered an oral presentation in English.

– When they made mistakes while talking in English.

– When they did not prepare well to speak.

– When they spoke English in a strange place.

– When they orally translated English to Japanese and vice versa.

b) Research question 2: How frequently do they face the language anxiety in English speaking performance?

The less successful learner reported feeling anxiety in more situations than the successful learner, especially when she took an English test or when she did not remember the vocabulary words, did not know what to speak or did not prepare well to speak (“always”), but both students felt anxiety “very often” when they did not know how to pronounce an English word.

c) Research question 3: How do they react to the speaking anxiety in those situations?

The successful learner reported that he was motivated or willing to continue the English communication in most speaking situations, whereas the less successful learner’s responses suggest she had fear or felt too shy to speak.

Some of the following implications should be noted for classroom English teaching strategies. First, teachers should encourage students to feel positive towards learning and think that making mistakes is an important part of learning new things. Students should be also encouraged to take risks when possible to experience different feelings in their language learning process. Next, it is important for teachers to select the learning tasks appropriately to make a balance in learning opportunities or both types of students (successful and less successful). Finally, creating a positive and relaxing learning environment would play a key role to promote students’ engagement in English learning.

This paper has some limitations, namely that participant selection was based on the researcher’s opinion, that the method involved using participants to translate other participants’ responses, and that it only focused on two learners. However, as an exploratory piece of research, its findings can be used to design a larger-scale research project to explore the under-researched topic of the differences between speaking anxiety in successful and less successful learners of English.

Notes on the contributor

Hung Nguyen-Xuan is an Associate Professor at the Project Education Center, Kanazawa Institute of Technology. He earned his MA-TESOL from Saint Michael’s College (the U.S.) sponsored by the Fulbright Program. His research interests include ESP teaching and learning, ESOL curriculum design, teaching innovations, and Design Thinking in education.

References

Cutrone, P. (2009). Overcoming Japanese EFL learners’ fear of speaking. University of Reading Language Studies Working Papers, 1, 55–63.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ryan, S. (2015). The psychology of the language learner revisited. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gan, Z., Humphreys, G., & Hamp–Lyons, L. (2004). Understanding successful and unsuccessful EFL students in Chinese universities. The Modern Language Journal, 88(ii), 229–244.

Gardner, R. C., & MacIntyre, P. D. (1992). A student’s contributions to second language learning. Part I: Cognitive variables. Language Teaching, 25, 211–22. doi:10.1017/S026144480000700X

Halbach, A. (2000). Finding out about students’ learning strategies by looking at their diaries: A case study. System Journal, 2, 85–96.

Harumi, S. (2010). Classroom silence: Voices from Japanese EFL learners. ELT Journal, 65(3), 260–269. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccq046

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. A. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125–132. doi: 10.2307/327317

Indrianty, S. (2016). Students’ anxiety in speaking English (a case study in one hotel and tourism college in Bandung). ELTIN Journal, 4(I), 28–39.

Khattak, Z. I., Jamshed, T., Ahmad, A., & Baig, M. N. (2011). An investigation into the causes of English language learning anxiety in students at AWKUM. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 15(2011), 1600–1604.

Kudo, S., Harada, T., Eguchi, M., Moriya, R., & Suzuki, S. (2017). Investigating English speaking anxiety in English-medium instruction. Essays on English Language and Literature [Eigo eibungaku soushi], 46, 7–23. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2065/00053662

MacIntyre, P. D. (1999). Language anxiety: A review of the research for language teachers. In D. J. Young (Ed.), Affect in foreign language and second language learning (pp. 24–45). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Philp, J. (2017). Cambridge Papers #1: What do successful language learners and their teachers do. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://languageresearch.cambridge.org/images/Language_Research/CambridgePapers/CambridgePapersinELT_Successful_Learners_2017_ONLINE.pdf

Rubin, J. (1975). What the ‘good language learner’ can teach us. TESOL Quarterly, 9, 41–51.

Sadiq, J. M. (2017). Anxiety in English language learning: A case study of English language learners in Saudi Arabia. English Language Teaching, 10(7), 1–7.

Suzuki, N. (2013). An investigation of Japanese students’ foreign language speaking anxiety in an undergraduate English-medium instruction (EMI) program. (Unpublished master’s thesis). The Graduate School of Education, Waseda University, Japan.

Thornbury, Scott. (2005). How to teach speaking. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Limited.

Townsend, J. & Danling, F. (1998). Quiet students across cultures and continents. English Education, 31, 4–25.

Williams, K. E., & Andrade, M. R. (2008). Foreign language anxiety in Japanese EFL university classes: Causes, coping, and locus of control. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 5(2), 181–191.

Zhiping, D., & Paramasivam, S. (2013) Anxiety of speaking English in class among international students in a Malaysian university. International Journal of Education and Research, 1(11), 1–16.

Dear Hung Nguyen-Xuan,

It was a pleasure to read your article on differences of a successful and less successful Japanese learner’s speaking anxiety.

I certainly agree that there is a fear of making mistakes with Japanese learners in the ELT classroom with the fear of negative evaluation amongst peers. I see occurrences within my teaching context in junior high school where learners have a reluctance to speak out in class and I try to find ways for my learners to increase their self-confidence in speaking. I am always on the lookout for new ‘‘strategies to cope with anxiety-provoking situations’’ (Dörnyei and Ushioda, 2013:121). I try the strategies mentioned in your article including appropriate learning activities for successful and less successful learners and I always set out to have a positive and relaxed learning environment to make the atmosphere more engaging for learners. I do however want to further encourage my learners to not worry about making mistakes when they speak as I think this is a positive element towards L2 learning and is something that I would like to promote more of with the teachers I work with at school.

I did enjoy reading the study you carried out with both learners. I thought the more successful learner supporting the less successful was a nice way to engage both learners in the study. I also believe that having additional English language experience abroad is an essential element towards boosting interest in culture and does wonders for self-confidence and motivation. I had a junior high school third grade learner come back from Canada on an exchange program last year and I felt her confidence in speaking English had dramatically risen, I was pleasantly surprised by how much more vocabulary she had learnt. She also contributes in class at every opportunity and not at all fearful on what other learners think.

I do believe learners need to have a strong motivation for L2 learning in order to decrease the anxiety to speak. L2 motivation has been a key research interest for myself and I believe teaching strategies should be carefully administered when planning lessons in order to combat speaking anxiety of learners. I like to refer to Dörnyei’s model of the Components of Motivational Teaching Practice in the L2 classroom (Dörnyei and Ushioda, 2013, Dörnyei, 2001) to remind myself on approaches that can be taken in lessons to increase self-confidence and decrease anxiety of leaners. I recommend both books referenced below as both include information on learner anxiety and L2 motivational strategies.

From reading your article, and if you had the opportunity to extend your research, it would be interesting to look at how teachers could support less successful learners further and which teaching strategies prevail to make these learners more successful in the ELT classroom.

I look forward to your next article.

Derek Herbert

References:

Dörnyei, Z. and Ushioda, E. (2013) Teaching and Researching Motivation. 2nd Ed. Oxon: Routledge.

Dörnyei, Z. (2001) Motivational strategies in the language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dear Hung Nguyen-Xuan,

Thank you for your study. It is always good to know what kind of situations cause speaking anxiety among learners. Here are some thoughts for further studies you might undertake.

I think though that we could probably assume that a more successful learner who speaks out a lot in class will have less anxiety and more confidence, and one who remains silent will have more anxiety and less confidence. In order to help your students more concretely, you might want to look at ways to investigate why a student like Student A has more confidence, and from that develop activities to decrease the confidence of less-successful learners, perhaps through a reflective activity which enables both type of learner to share their experiences. Do the more successful learners consciously employ strategies to help themselves? Have they developed a different set of beliefs concerning their own abilities? This kind of information will inform your class.

As you know, students care deeply about what others in class think of them, and often make comparisons between their own abilities and that of their peers. More successful learners can serve as role-models for anxious students if the situation is correctly handled. Look at Tim Murphey’s 1998 paper on ‘Motivating with Near Peer Role Models’ for some good information.

In terms of recruiting students, you might want to ask for the participation of the class as a whole, or ask the permission of other teachers to conduct your survey with their classes. You will probably end up with far more interview subjects.

Good luck,

Neil Curry

Dear Hung and Neil,

I think Neil asks some really good questions here, namely: ‘Do the more successful learners consciously employ strategies to help themselves? Have they developed a different set of beliefs concerning their own abilities?’

In your (Hung’s) current study, I don’t think you have enough information to address the second question at this point. However, the information you have in your results table (though not so much your discussion section yet) has some pointers towards the strategies they use to counter anxiety, or at least the areas in which the two learners’ strategies differ. You might want to think about which area(s) you would focus on in either a future research project or making interventions in class.

All the best,

Huw

Dear Huw,

Thanks for making Neil’s idea clearer to me. I will make some changes to my article soon and I hope to have your continuing help!

Best,

Hung

Dear Neil,

Thanks a lot for your useful comments and suggestions to my article. It is a very good idea to investigate whether the more successful learners have developed a different set of beliefs concerning their own abilities when they speak English. The successful learner in my study seemed to have used some good techniques to deal with speaking anxiety. Your suggestion for further studies related to this point is very useful for me.

Best regards,

Hung

Dear Derek,

Thank you very much for your inspiring comments and suggestions to my article.

For many Japanese learners of English, it is difficult to encourage them not to worry about making mistakes when they speak due to their cultural inhibitions (because they actually feel worried!). However, I agree that teacher’s continuing encouragement is very important to create a stress-free learning environment for students, especially less successful students.

Your example of an exchange student is a great one to contribute to the fact that having additional English language experience abroad can be an advantage in English learning and can reduce students’ language anxiety.

Thank you for the books about motivational practice you recommended. I like your idea of how teachers could support less successful learners particularly in a further research because I have only mentioned some general teaching implications for classroom English teaching strategies in my article. It seems good to go further!

Regards,

Hung