Hatice Karaaslan, Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University School of Foreign Languages, Ankara, Turkey

Karaaslan, H. (2020). Advising lessons learned from learner reflections. Relay Journal, 3(1), 55-65. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/030105

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

This short article presents the findings from action research conducted with sixty EFL students at an English-medium state university in Turkey over a period of eight weeks. The study was aimed at eliciting student needs as to the cognitive, interactional, and learner-related aspects of the language learning process by employing task-based learning applications. The tasks, both online and face-to-face in class, focused on productive skills and were designed with a consideration of task features including complexity, conditions and difficulty (adapted from Robinson, 2001), helping students observe their progress. Content-wise, they were based on themes studied in the course materials. Advising strategies and tools were incorporated in the design, delivery and flow of the lessons as well. The needs identified upon the completion of the study were utilized to draft future advising policies and practices aiming to equip students with academic survival skills. To collect data on learner reflections regarding the process, thirty students were asked to complete an open-ended self-report questionnaire, while the rest participated in a focus group discussion. Both groups reflected on their task-based learning experiences with respect to the cognitive, interactional and learner-related factors involved to provide insights for potential advising policies and practices.

Keywords: Higher education, advising, perceived support, student reflections, task-based learning

Context and Background

With the incorporation of Internet technologies and distance education tools in today’s classes, are we, as educators, making important sacrifices to accommodate them and disregarding the significance of human touch? Do learners, the so-called digital natives, actually benefit from this educational process and make meaning out of these experiences? Or do they suffer from a lack of quiet contemplation which, if it existed, would pave the way for meaning-making? Do we often talk about student control of learning, tests, standards and outcomes, achievement or efficiency but rarely concentrate on the once-appreciated values of human judgment, including personal growth and character, meaning, insight, wisdom and intellectual creativity? Not necessarily. However, we still need to make sure that these values are cared for, and this is where counseling, or particularly advising in our context, comes into play.

Holding this perspective, this study was carried out in the School of Foreign Languages (SFL) at an English-medium state university in Ankara, Turkey over a period of eight weeks. The target population consisted of the “repeat” students that are in their second year in the English preparatory program. In this program, students are placed in different levels based on their program-entrance language scores. They take the proficiency exam once their first one-year study period is over, and they are required to study in the English preparatory program again if they fail to get a passing score. In their second year, these students receive online training on reading and listening and face-to-face in-class training on writing and speaking as part of a blended learning program.

This format and content build on the idea that it is essential to provide some flexibility in schedules in order to address individual needs and ensure face-to-face feedback on student performance. “Advising in language learning was considered a reasonable option to assist our students in their autonomy-building process” (Uzun, Karaaslan, & Şen, 2016, p. 85), and the Independent Learning Center (ILC) at SFL established the Learning Advisory Program (LAP). The LAP service offered by two full-time ILC instructors at the time primarily addressed these repeat students and included 20-minute advising sessions on topics such as language skills and learning strategies, study skills, exam skills, anxiety and fear of failure. With the expansion of the Learning Advisor (LA) team at the school, a larger portion of the students enrolled at the university started to benefit from this LAP service, which was then offered in a variety of forms, such as 30- to 45-minute one-on-one advising, online or written advising via e-mail, classroom-based as well as peer or group advising.

The theoretical framework and practical applications followed in the operationalization and functioning of this LAP while helping learners become autonomous build on what Kato and Mynard (2016) offer in their reflective dialogue and how they approach transformational learning. In this methodology, learners, by engaging in intentionally structured reflective dialogue under the guidance of advisors (utilizing advising tools when necessary), become aware of their needs and interests in language learning and explore and find solutions to the root causes of their struggles. Going beyond improving language proficiency is the ultimate goal to be attained by raising awareness of learning, translating the learner’s awareness into action and making a fundamental change in the nature of learning.

This specific study was an attempt by the instructor–researcher, a trained advisor herself, to exploit advising strategies and tools in a classroom context in two of her repeat classes. The three principles of advising—focusing on the learner, no assumptions and no judgement (Kato & Mynard, 2016)—were considered in all phases of the teaching and learning process, including content planning and design, content delivery, instruction and interaction, classroom atmosphere and management and assessment and feedback. Further, the relationship between the affective and cognitive factors is bidirectional and integrated, with emotion being influential on memory, attentional resources, information processing strategies, and thus on cognition, motivation, learning and performance (Forgas, 2000; Schunk, Pintrich, & Meece, 2008). Hence, affective strategies were also incorporated in the design, delivery and flow of the lessons. Among the affective strategies of rewarding oneself, positive talk, enhancing interest, reframing attributions, regulating emotions and scenario-based applications, the instructor–researcher adopted the strategies of positive talk and reframing attributions, as she wanted to focus primarily on motivation and management of emotions, beliefs and attitudes.

These students needed to feel valuable and capable, to build positive self-images and to see that people care for them. Therefore, the lessons were intended to exercise detachment (from the negative feelings associated with being a failed, insecure repeat student), reframe attributions, break the negative cycle and achieve a positive climate in class, by utilizing metaphor use predominantly in various reflective speaking and writing activities (see Appendix for activity ideas). The idea was to promote the belief that they had the potential all the while but just needed time to reveal it. This perspective also entailed being hopeful and optimistic, welcoming change and diversity, and expanding and spreading all that positivity. It was obviously felt by the students as one student, in his end-of-term e-mail to the instructor–researcher, said, “You have been our mentor, our support, and our guide. You taught me how I can go into the real world and be confident about who I am and what I can achieve.”

In addition, these students seemed to lack basic language learning strategies and had relatively low levels of competence in terms of language skills, despite being placed in intermediate-level language groups. Thus, the instructor–researcher also aimed to uncover the cognitive, interactional and learner-related challenges these students might be facing being exposed to a blended learning program, in which they were offered only one third of the face-to-face instruction regular English preparatory program students receive, in addition to online reading and listening training. To this end, students were offered online and in-class task-based learning activities. The ultimate goal in this action research was to identify the challenges, to design and adapt future advising policies and practices accordingly and to contribute to students’ attainment of academic survival skills.

Task Design and Training Materials

The current action research was designed and implemented as a needs assessment tool to guide the planning of subsequent advising activities. Sixty intermediate-level repeat English preparatory school students (predominantly male with an age range of 18–21) participated in this study, engaging in task-based learning over a period of eight weeks. They completed a set of writing and speaking tasks: six online and seven face-to-face. The tasks, both online and face-to-face in class, focused on productive skills, including writing and speaking. They were developed in accordance with task design features such as complexity, conditions, and difficulty suggested by Robinson (2001). Content-wise, they were based on themes studied in the course materials.

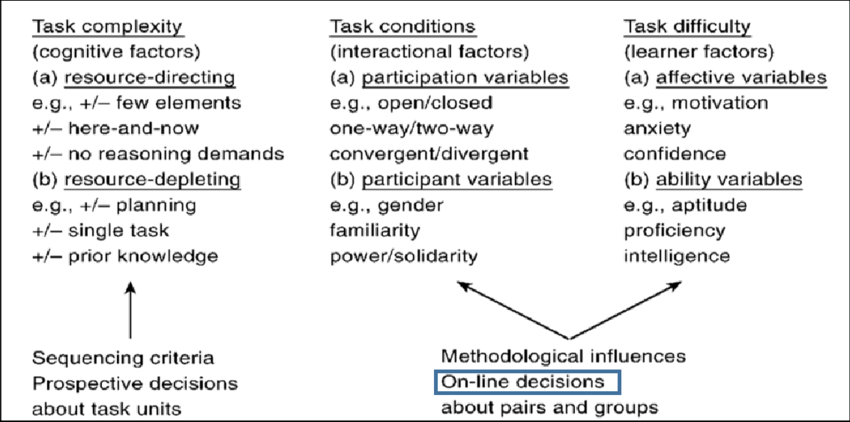

Students, as a supplement to in-class and online instruction, need to be provided with opportunities to apply and experiment with the newly acquired knowledge and skills in novel ways and to learn by doing or engaging in experiential learning (Dewey, 1933). Tasks, in this respect, serve an important purpose in educational settings, and their design and delivery become quite critical in encouraging student effort and boosting performance. In alignment with Robinson’s (2001) argument, task differentials in terms of complexity, conditions and difficulty are “fixed and invariant features of the tasks,” and their systematic use “will help explain within-learner variance” (p. 30). His proposal regarding task design features with reference to task complexity, conditions and difficulty is displayed in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Task complexity, condition and difficulty (adapted from Robinson, 2001, p.30).

As is illustrated in the figure, task complexity refers to cognitive factors, conditions to interactional factors and difficulty to learner-related factors respectively. By manipulating the task differentials and conditions (including the number of task elements, time and place references, reasoning demands, prior knowledge requirement and planning; interactional patterns, participant and participation variables and learner factors that relate to affective and ability variables), tasks that facilitate content and application attainment can be designed.

For the purposes of the current study, six online and seven face-to-face in-class tasks were designed and delivered. The tasks included:

- Read the text provided and write a response to it in a paragraph of 125 words (face-to-face in class),

- Research and write about traditional ways of curing an illness (online),

- Interview a classmate about their study habits and present a short oral report of it in class while at the same time giving advice if they have poor study habits (face-to-face in class),

- Prepare and present a smartphone application that will help people stay healthy (online),

- Prepare a Kahoot vocabulary game based on the weekly vocabulary list (face-to-face in class),

- Write a paragraph to make a prediction about the survival of the Penan (online),

- Write a cause-and effect-paragraph of 150 words about one of the following topics: the reasons why people do sports or the effects of games on children (face-to-face in class),

- Express opinions about the quotes on motivation (online),

- Use pictures that tell a story or message (Google for pictures with a story or message) and talk about the message or story behind for about two minutes (face-to-face in class),

- Write a paragraph about the pros and cons of building a colony on Mars (online),

- Ask and answer questions based on the prompt cards provided (face-to-face in class),

- Find advertisements for the same type of product (e.g., cars) from two different companies and analyze them (online),

- Write a well-organized opinion essay of 200 words about the following topic: “Do you think social networking sites (such as Facebook) have had a huge negative impact on both individuals and society?” (face-to-face in class)

Upon the completion of the implementation period, one of the classes was asked to complete an open-ended self-report questionnaire while the other participated in a focus group discussion. Both groups reflected on their task-based learning experiences with respect to the cognitive, interactional and learner-related factors involved, as suggested by Robinson (2001) in his explanation regarding task design features. The open-ended questions employed in both data collection sessions included the following:

- Task Complexity: Are there enough elements or steps? Is it necessary to collect information from readings, Powerpoint presentations or video content? Are there reasoning demands such as analysis, synthesis, etc.? Are these activities beneficial?

- Task Conditions: Is it open-ended or multiple choice? Does it require interaction with others? Does it require familiarity or solidarity? Is it challenging?

- Task Difficulty: Does it help with emotional states such as motivation, anxiety or confidence? What kind of abilities, including language proficiency, academic aptitude or intelligence, does it require? Are these activities beneficial?

The data were compiled and subjected to content analysis. The content analysis (Creswell, 2012) was conducted following the steps of organizing the data, exploring and coding the data, constructing descriptions and themes, identifying the qualitative findings, interpreting the findings and validating the accuracy of the findings. During the data analysis, the responses compiled from the self-report questionnaire and the transcribed spoken data from the focus group discussion were read individually and grouped based on student reflections regarding task features and emerging student characteristics. The explanations were aligned with these findings, and then the results were interpreted in relation to potential ideas for future advising policies and practices.

Findings and Discussion

The findings from the self-report questionnaire responses and the focus group discussion transcripts revealed the following research highlights in relation to teaching and advising practices.

In a class of 30, where students have been placed based on their language test scores, homogeneity is not always guaranteed, as the standardized tests may not reveal students’ actual competence levels in language and survival abilities in academic contexts. The findings from the current action research, as well as the instructor–researcher’s observations, provide supportive evidence in this respect such that some students reported having found both types of tasks, regardless of being face-to-face in class or online, challenging due to the difficulty they experienced in understanding task instructions and using academic language, while others thought that the tasks were structured well, the stages were clear and the requirements were manageable.

In this sense, teaching, as well as advising, is essentially a craft of meticulous, consistent and constant analysis of student needs and expectations. Task use, or tool use in the case of advising, with a consideration of the challenges individual students might be experiencing and tailored or updated on the go based on the incoming information, could prove an effective application in revealing learner-specific characteristics. To illustrate, an online speaking task returns better results with lower-achieving students, as students themselves report referring to the advantages of lower anxiety, higher self-confidence, longer preparation time and opportunity to do the task multiple times until they are contented with their performance. Similarly, during an advising session, when the advisee does not seem very responsive and a lengthy silence puts him or her in a more difficult situation, the use of less structured tools, such as metaphors, viewpoint-switching sheet or drawing, and not relying solely on linguistic expression might help him or her open up and engage in deeper reflection.

With online tasks, some students find it difficult to follow instructions, get confused or distracted easily and misunderstand what is required of them. They require individual, personal attention and end up contacting the instructor many times through e-mail, resulting in a lengthy sequence of exchanges, which is in essence an inherent feature of the meaning-making process and thus requires a careful reading of the situation by the language instructor–advisor. Such intentional, reflective dialogue, online or face-to-face, is the core concept around which transformational advising evolves (Kato & Mynard, 2016). Instructors and advisors could take advantage of such requests revealing learners’ immediate needs and encourage them to engage in deeper reflection with the help of powerful questions or viewpoint-switching tools.

Some students find open-ended tasks loosely structured and thus challenging, while others appreciate them due to the variety and creativity allowed. The latter group also finds them engaging for being able to develop vocabulary and world (topical) knowledge, gain new perspectives and think critically, prepare for exams and achieve peer interaction. Thus, instructors and advisors are advised to differentiate between the two profiles and tailor their teaching and advising accordingly. In the case of advising especially, relatively dependent learners could be approached in a more directive manner, at least in the initial stages, as this could also help with rapport- and trust-building.

When they find tasks challenging, some students report having given up working on them altogether, due to feelings of learned helplessness, but they do not seek online or face-to-face help, either from their peers or from the language instructor. Although there is help available online or in person, such channels are not explored, and therefore perceived support is limited. Differences emerge with respect to teaching and advising students with varying emotional states (e.g., motivation, stress-management, anxiety, self-confidence or self-efficacy).

Some students, though performing only at an average level, use compensation strategies effectively. For instance, some students are outspoken and easygoing, and they can speak quite fluently despite the grammar and word choice mistakes they make in their speech. They like taking the initiative and create a positive atmosphere in class. However, other students tend to have a fixed mindset about their performance and fear failure, refraining from taking active part in class or forum discussions. Teaching and advising practices need to involve not only individual but also peer or group combinations such that students with varying skills and strategies can support each other in significant ways.

Some students still retain their old, obsolete study habits from high school, are not aware of their responsibilities in an academic environment and thus get disappointed and discouraged in the face of challenges. What one student stated regarding task use reflects this tendency to stick to old study habits, which in fact does not help much with language learning: “The tasks require a lot of research and vocabulary study, which makes me lose much time; but I want to focus on the tests that prepare me for the general proficiency exam. The instructors should administer mock exams frequently.” On the other hand, others have a desire to leave their comfort zone and live their new life as an experiment—taking risks, challenging assumptions, trying different things and not being afraid to push boundaries, as stated by one: “I love the tasks, especially the online ones. I am not under any stress and this makes me get in a state of flow and come up with very interesting ideas,”—but the fear of failure or poor scores stand in their way.

As such, incorporating advising strategies and tools in language learning can help learners closely observe and analyze their learning processes, set and achieve their goals as language learners, take charge of their learning and improve the quality and depth of their learning. In addition, they can increase their capacity for self-evaluation and decision-making in a world with huge technical power, but with human purpose to shape its use.

Along this line of argument, it would be advisable to encourage all language instructors to receive training at least on the foundations of advising in language learning and on the primary strategies that could be utilized in building rapport and trust, reframing attributions to promote positive talk and positive thinking, switching viewpoints and perspectives, and adopting a growth-oriented mindset (Dweck, 2014).

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Fund (BAP) at Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University, Turkey, as part of Project 3934 in the 2017–2018 academic year. The preliminary findings were presented at the 27th International Conference on Educational Sciences (April 18–22, 2018) in Antalya, Turkey with the title “Advising Strategies: Reframing Attributions to Embrace Growth Needs.” The author wants to dedicate this full paper to the people who passed away during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic in the world.

Notes on the Contributor

Hatice Karaaslan, holding a Ph.D. in Cognitive Science from Middle East Technical University and Learning Advising Certificates from Kanda University of International Studies, works as an EFL instructor and a Learning Advisor at Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University School of Foreign Languages, Turkey. Her interests include corpus linguistics, critical thinking, blended/flipped learning, self-determination, and advising in language learning. hkaraaslan@ybu.edu.tr

References

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Boston, MA: Henry Holt.

Dweck, C. (2014, November). Carol Dweck: The power of believing that you can improve [Video]. TEDxNorrkoping. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/carol_dweck_the_power_of_believing_that_you_can_improve

Forgas, J. P. (2000). Feeling and thinking: Affective influences on social cognition. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. New York, NY: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

Robinson, P. (2001). Task complexity, cognitive resources, and syllabus design: A triadic framework for examining task influences on SLA. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction (Cambridge applied linguistics) (pp. 287–318). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524780

Schunk, D. H., Pintrich, P. R., & Meece, J. L. (2008). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall.

Uzun, T., Karaaslan, H., & Şen, M. (2016). On the road to developing a learning advisory program (LAP). Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(1), 84–95. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/mar16/uzun_karaaslan_sen/

[Appendix]

Integrating advising techniques as a support for learners as a kind of support in the language class is an effective way to make students aware of their learning. Actually, if we think the times we are living now in this new normal, when teaching has been relocated to virtual environments, autonomy in students and teachers is one of the many concerns and I think the results you present are encouraging. Actually, the student outcomes can be a way to deal with this new way of attending students in this emergency teaching, because we need to promote in our students’ learner responsibility, but also strengthen emotional skills.

Your research focussed on remedial work for language students, which makes me think that these undergraduates still need to improve their language learning strategies; however, there were positive changes in them. I wonder if this model of advising tools in classroom can be applied to regular students in order to enhance their learning just as it happened in your study. What do you think?

As we know autonomy can mean controlling, content, task, emotions, activities and some other dimensions that intervene in the learning process. One of them that I find relevant is that students achieved a feeling of being able to build a positive image of themselves, which one truly one of your objectives when you decided to apply advising techniques. I can assume that through advising techniques this was possible. Have you identified if this transformation was a result of the combination of tasks and advising or do you considered advising was fairly crucial for it?

I am also intrigued how the teacher applied the advising methodology; can you describe a bit more how it took place? How was advising included in the task? The students’ comments reveal advising was important for their learning process- besides activities.

The article finishes with a strong recommendation to have teachers take a sort of advisors training as a way to improve the teaching practices, because it is a essential to have a different way of approaching to learning and teaching. I entirely agree with you. My experience is just like yours. Once we are involved as an advisor, our teaching practice transforms and the interactions with students isn’t the same.

So, the fact that the person in charge had a specialized training is a decisive factor in this study and the students change. What did you learn as an advisor from this experience? What would you recommend for people who would like to apply it to their courses?

Looking forward to your answers.

Adelia

Dear Adelia,

Thank you very much for this thoughtful and very constructive feedback and response! It will be my pleasure to walk through the article with you and touch upon the points requiring further elaboration.

I think applying this model of advising (strategies and tools) in classroom to regular students can certainly support student effort and enhance their learning experience. That is something we, as the LAs at my institution, do inevitably and kind of effortlessly in all the classes we teach, be it a repeat/blended class or a regular class, and we get very positive feedback from our students. They talk about how their mood improves, how they feel supported and cared for, and most importantly, how their perspective and attitude regarding learning in general, not just toward language learning, change as a result of their interaction with us as their instructors and the time they spend in the positive classroom atmosphere created with the incorporation of advising principles (focus on the learner, no assumptions, no judgement).

In response to your next set of questions “Have you identified if this transformation [students building a positive self-image] was a result of the combination of tasks and advising or do you consider advising was fairly crucial for it?..How was advising included in the task?” I must say both the tasks and the ALL perspective incorporated helped to make progress in this sense. The tasks were scaffolded in such a way that even the least promising students were able to engage in the learning process and come up with some written or oral product at the end; they were allowed enough time and space and received continuous feedback on their work to achieve mastery gradually at their own pace. As such, it is really hard to isolate such classroom practices or pedagogical choices from the principles and practices suggested in ALL; they are kind of interwoven in an untraceable manner. A good instructor, just like an advisor, has a careful eye and patient ear responding immediately to the emerging needs of their students and improving the content and its delivery in new, creative ways. So although the direction in a teaching-learning situation is said to be planned and quite predictable, seemingly very much different from the advising context, in fact it is not, if the ultimate goal is student agency and ownership of the learning process. Otherwise, content attainment by the student is quite unlikely. Thus, my experience, as demonstrated in this action research, is just like yours: “Once we are involved as an advisor, our teaching practice transforms and the interactions with students isn’t the same.”

And eventually this experience has assured me advisors teaching courses to students in addition to holding advising sessions with advisees are already applying ALL strategies and tools in their classes effortlessly; it is in them and reflected in everything about them. So I would just tell them to enjoy it to the fullest with no reservations or questions in mind as students love and appreciate it! And these pandemic days, as all our students require both academic and significant emotional support, are the best time to ALLise our classes!

Thank you very much once again for taking your time posting this very reflective comment and stimulating deeper contemplation on the text!

Best wishes and stay safe,

Hatice-