Tim Murphey, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan

Curtis Edlin, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan

Murphey, T. & Edlin, C. (2020). The EcoEducational-BioPsychoSocial model in everyday education: A suggestion for researching holistic well-being as a contribution to healthier learner autonomy. Relay Journal, 3(1), 110-121. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/030109

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

In this short article, we propose that education could benefit greatly if students and teachers were tuned into the biopsychosocial parts of our holistic well-being, which is considered to be autonomy supportive, as a prerequisite of learning. Thus far, education has largely operated on a bias toward cognitive processes as the sole meaningful contributor to learning, focusing on the acquisition of knowledge while often seeing the biological, psychological, and social contextual contributions as unrelated. With the recent generation of positive psychology and positive sociology, researchers and educators alike are becoming more aware of the contribution that contextual well-being (i.e. considering biopsychosocial factors) has upon learning. This growing awareness suggests the need to broaden rather than narrow our understandings of causality both in the classroom and with learning at large. We propose that showing attention to this wider context could improve student learning substantially and support student development of a more sustainable autonomy.

Keywords: educational ecologies, biopsychosocial model, well-being, positive psychology and sociology

There are times in our classrooms when students’ behavior-learning connections should not be ignored. Examples might include when our students are nodding off in otherwise interesting classes, when they are running constantly to the bathroom, when they continually sit in the back as far away from others as possible, when they chronically come late and dart off quickly at the bell. These students may be suffering from biopsychosocial problems that are disturbing and limiting their educational endeavors. This is natural as students live the vast majority of their lives away from our classrooms and yet are still bringing the rest of their worlds to class with them through their biologies, psychologies, and sociologies. In this article we propose that showing at least a modicum of attention to this wider context could improve student learning substantially.

The BioPsychoSocial Model

We both independently first read about the biopsychosocial model in Deci & Flaste (1995, pp. 170-173) in late 2019. Tim then further educated himself with several articles which describe and expand on the ideas (Borell-Carrió, 2004; Reisinger, 2014), while Curtis read and considered further about its relation to performance (Cotterill, 2017). Although Tim had heard from a variety of sources over the years that “everything is connected,” such as in some highly recommended TED talks by Tom Chi (TED, 2016) and Robert Sapolsky (2017) and from his father when he was a teenager, he was not aware that the medical field in particular had had a hard time breaking away from what was known as the biomedical model, in which medical doctors mainly looked at health only in terms of the physical body and ignored other possible psychological and social influences. Engel and colleagues produced a more expansive positive model called the biopsychosocial model (Engel, 1977). There have been several articles on its application to special needs education (Reisinger, 2014), but there is little about its application toward education at large, which could also align positive psychology and sociology with our learning goals. We would like to begin taking this next step in this article.

Background

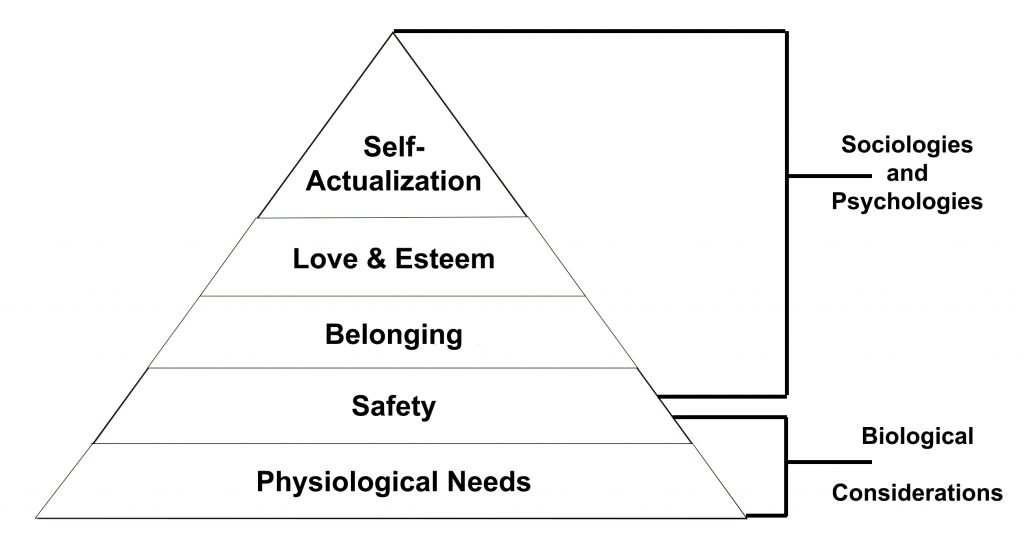

One vastly influential connective scheme from the 20th century was Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (1943). While the bottom two layers of the hierarchy are mostly biological and understood to underpin the upper layers, those upper layers have mostly to do with our psychologies and socialization (see Figure 1). All layers are likely to affect each other and may be pre- and corequisites of effective learning.

Figure 1. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

There may be certain moments in one’s life when we might observe things as more obviously connected to each other, that in fact these different elements of our lives cannot really exist without each other. To some, it may sound ludicrous to separate them. However, in much of science, medicine, business, and education, we often try to isolate the variables of phenomena in order to try to understand those variables more concretely, which makes learning them simpler. While this might work sometimes in pure sciences, such as chemistry, in other domains, the systems and variables that influence and affect a variable can be inextricable from each other and thus disallow us to truly isolate that variable. When we still approach our knowledge and answers through that isolation, our solutions may in fact suffer from that very isolation, not properly accounting for other related and causal factors. The scientific method seeks to isolate and purify a causal event. In our modern world though, we are finding that nearly everything is connected to and influencing everything else, and a great deal needs greater contextualization, perhaps in a dynamic systems way of thinking (Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008).

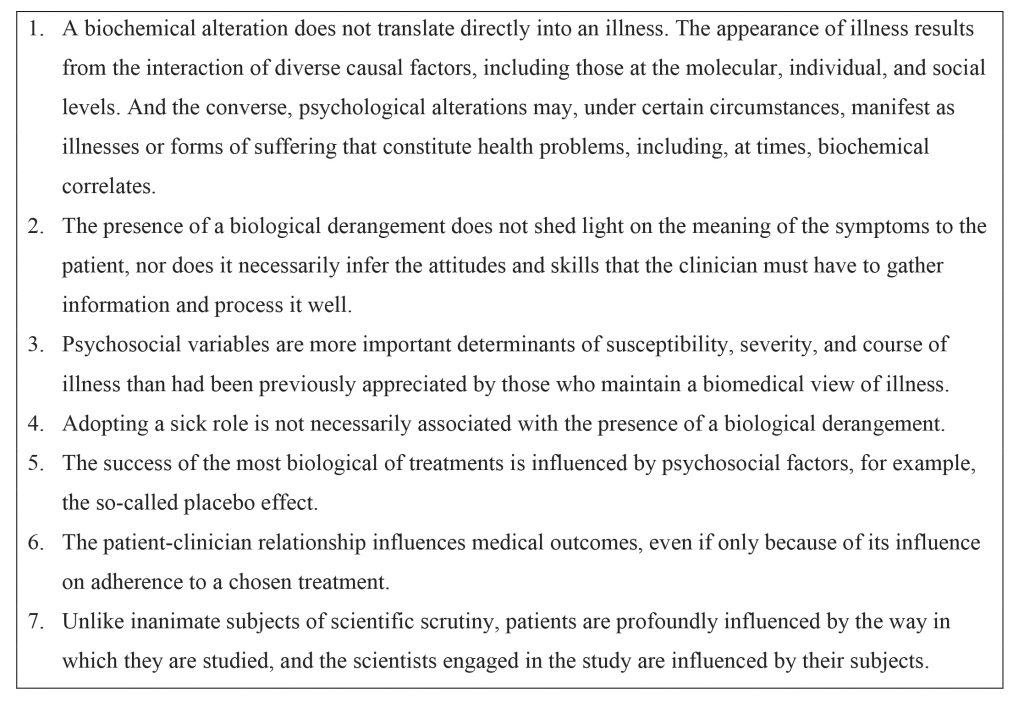

Many medical practitioners have long known these ideas, and while they seek to be specialists in one or two domains, they are in today’s world tasked with continual learning from neighboring fields. Psychologists no longer just study psychology, but rather social-psychology, clinical psychology, cognitive psychology, developmental psychology, evolutionary psychology, forensic psychology, health psychology, neuro-psychology, educational psychology, and occupational psychology (to name just a few). However, these subfields are reductionist, i.e., looking more narrowly at particular kinds of psychology, not seeking to expand but rather to reduce the scope of the fields in order to make them more understandable for specific needs. This sort of reductionism is often apparent in teaching within subject domains as well. Engel’s critique of biomedicine (as reductionist) is summarized in Figure 2 below (from Borrell- Carrió, Suchman & Epstein, 2004). Carl Jung (1957) offers another example (see Appendix A).

Figure 2. Engel’s Critique of Biomedicine

Parallels in teaching

We are in no way suggesting that teachers in the classroom are doctors nor that we are treating medical problems. However, we think that teachers will recognize that their students are also situated partially in parallel with the descriptions above, in that all students learn somewhat differently from each other and when afforded one-to-one counseling or advising directed toward individual situations, they seem to blossom and thrive. This is certainly also one of the powerful soothing effects of schools opening self-access centers that offer one-to-one advising (Mynard, 2019), which may derive from the idea that advising is autonomy-supportive and thus engenders more energy, vitality, and health (Ryan & Deci, 2008). We hope that good friends and teachers have good “bedside manners” that show respect and helpfulness and engage students for better well-being, which we predict will be followed by more successful, autonomy-supportive education.

In the Classroom: Broadening What We See; Start Small

As mentioned above, there are times when behavior-learning connections cannot be ignored and for which a simple or narrow explanation may not suffice. A simple explanation may not be enough for us to understand what is happening and interact in a way that is optimally beneficial and autonomy-supportive for our students. A student who is falling asleep in class may have a psychological media addiction to computer games and be playing all night, possibly be working at part-time jobs until 2 a.m. each night to pay for student loans, or be living alone for the first time and just not regulating herself well. An overly narrow view (that the student just needs to exert more effort) with an overly narrow solution (simply admonishing such a student to “pay attention” as if it is a simple issue of straightforward effort regulation) is not likely to help address the root problem and may in fact become a further wedge between herself and the class, including at a motivational level. The implication that her difficulty is a mere, simple lack of effort regulation can elicit a perception of failure and a discrepancy between who she is and who she feels she, herself wants to be or ought to be; or between who she is and who others want her to be or think she ought to be. Some negative potentials of such various discrepancies are feelings of low self-efficacy, shame or embarrassment, guilt, and anxiety, to name a few (Higgins, 1987). Along with a feeling of low self-efficacy, this perception of failure can also trigger a potential negative shift in the boundary between perceiving these discrepancies as challenges or threats (Cotterill, 2017).

The opposite of narrowing is expanding, which Grinker (1964) proposed as eclecticism and which Engel expanded on later with the biopsychosocial model, suggesting it replace the old biomedical model that ignored the parts played by our minds and societies. The biopsychosocial model has of course also been criticized as too eclectic, i.e., “anything goes” and thus sometimes “unscientific,” as humanism currently tends to be. While it has been applied to special educational needs (Reisinger, 2014), it has not been widely applied to general education. Our contention is that it should be applied to everyday education, just as civility (Porath, 2016).

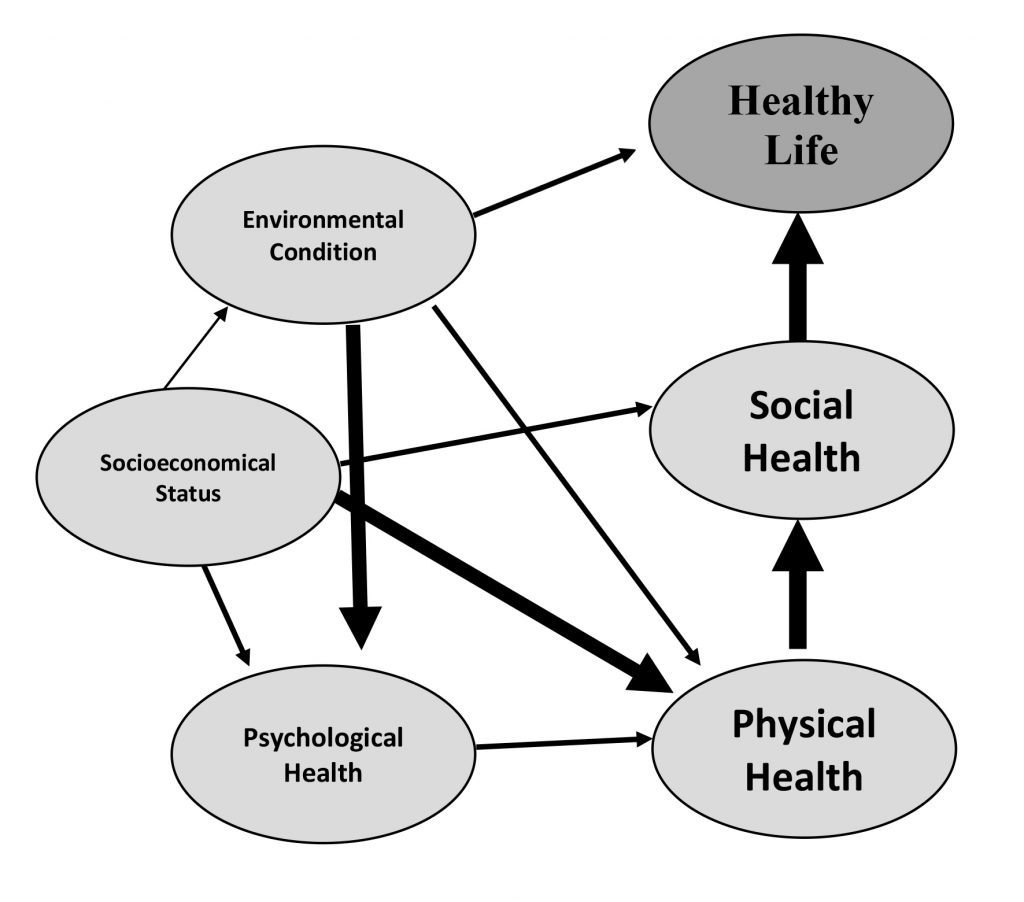

In the field of educational linguistics, we often unnaturally treat grammar, vocabulary, spelling, writing, and speaking as separate and distinct. While we can learn them in this way for a short time, sooner or later we are using them all together in a blend that we call communicative second language acquisition. This is similar to how medical scientists have long separated and specialized on parts of our bodies in hopes of better understanding them. While this intense specialization in a variety of fields has indeed rewarded us with great knowledge, its overemphasis can also make us blind to other contributing factors to health and successful practice at times, across any number of domains. With a broader understanding of contributors of illnesses, we might improve our control over illnesses and create better experienced longevity. One recent addition to this area is the book by Hoshi and Kodama (2018), in which various studies have been correlated to show how environmental, psychological, and social well-being (among other factors) contribute to a healthy longevity (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. The Structure of Healthy Life Determinants, adapted from Hoshi & Kodama (2018)

Similarly, if we can take a broader understanding of the environmental contributors to language learning and how they are situated in student lives, perhaps we can approach pedagogy in a way that is more effective in supporting both sustained learning and supporting its integration as part of a biopsychosocially healthy life.

Application in a sample activity

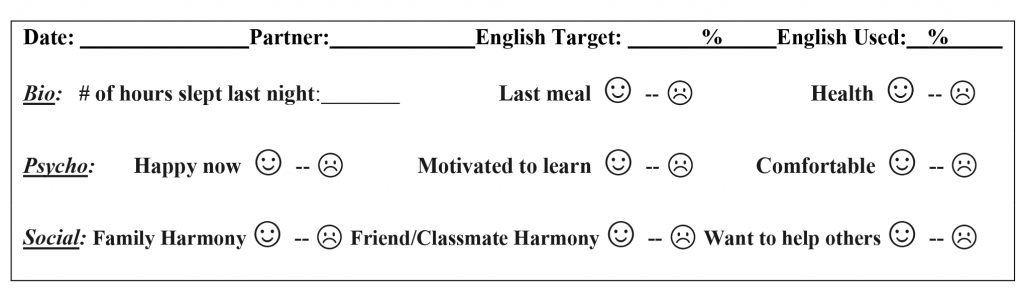

What we wish to propose here is construction of an ecological educational model that looks more closely at the attributes of the biopsychosocial model and combines them into an eco-educational biopsychosocial model for teachers. One practical way to apply these ideas is by simply asking our students to discuss them. Tim has experimented with this in the initial five minutes in every classroom with his students’ action logs, which are similar to classroom diaries (Hooper & Murphey, in progress; Miyake-Warkentin, Hooper & Murphey, in progress; Murphey, 1993). He asks students to share action logs that they have written and check in with each other that they are okay, that is to say sufficiently healthy and eager to learn. He often asks them to ask each other about their bio-conditions (e.g., “How much sleep did you get last night?” “Did you have a good breakfast or lunch?” see Appendix B). He wishes to expand this focus in the upcoming semester when students do action log shares. He is going to ask that they add in the data about themselves in form depicted in Figure 4 and talk things over with their partners. He hopes that this will help them to tune into their biopsychosocial prerequisites as a base for learning as well as give him valuable information about the students’ lives.

Figure 4. Student Self-Assessment of BioPsychoSocial Well-Being and Readiness to Learn

Next Steps

Invitations to use activities, do research, and make the world a better place

If interested in borrowing and adapting the activity and process described above for classes or as research, we invite readers to do so. While we think action logging would be an appropriate way for students to engage with the ideas of holistic well-being and the BioPsychoSocial model, please feel free to engage with the ideas in ways that are ecologically fitting for you and your students (and any research constraints). For example, some of you may just try the simple questionnaire at the beginning, middle, and end of term, rather than try it daily in class. For further discussion on the EcoEducational-BioPsychoSocial Model, contact Tim or Curtis, the authors of this article.

Applications and outcomes

We hope to show in future research and articles that by becoming more attuned to contributing influences (BioPsychoSocial) upon growth, well-being, and learning that we can help students deal with those influences and create better learning environments for everyone.

Notes on the contributors

Tim Murphey is a visiting professor at Kanda University’s Research Institute of Learner Autonomy Education (RILAE). He also teaches at Wayo Women’s University Graduate School of Human Ecology, Aoyama University, and Nagoya University of Foreign Studies Graduate School. He publishes and presents passionately with others and presently researches community potentials. For further discussion on this topic feel free to contact at mitsmail1@gmail.com.

Curtis Edlin is a senior learning advisor working in the Self-Access Learning Center at Kanda University of International Studies. Some of his current research interests include advising practices, motivation, self-determination theory (SDT), and performance psychology in learning. Feel free to contact him at edlin-c@kanda.kuis.ac.jp for further discussion on any of these topics.

References

Borell-Carrió, F., Suchman, A., & Epstein, R. (2004). The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: Principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Annals of Family Medicine. 2(6), 576-582. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.245

TED. (2016, January 11). Tom Chi: Everything is connected—Here’s how [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rPh3c8Sa37M

Cotterill, S. (2017). Performance psychology theory and practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

Deci, E., & Flaste, R. (1995). Why we do what we do. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129-136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

Engel, G. L. (1979). The biopsychosocial model and the education of health professionals. General Hospital Psychiatry, 1(2), 156-165. [Originally appeared in, 310: 169-187, June 21, 1978. Reprinted with permission] (Presented as the 23rd Cartwright Lecture, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, November, 1979, under the title “The Biomedical Model: A Procrustean Bed?” https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-8343(79)90062-8

Engel, G. L. (1980). The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. American Psychiatry, 137, 535-544. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.137.5.535

Grinker, R. (1964). A struggle for eclecticism. American Journal of Psychiatry, 121, 451-457. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.121.5.451

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94, 319-340. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319

Hooper, D., & Murphey, T. (in progress). Action logging: A source of collaborative communities. Manuscript in preparation.

Hoshi, T., & Kodama, S. (Eds.) (2018). The structure of healthy life determinants: Lessons from the Japanese aging cohort studies. Singapore: Springer.

Jung, C. G. (1957). The undiscovered self. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company.

Larsen-Freeman, D., & Cameron, L. (2006). Complex systems and applied linguistics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Miyake-Warkentin, K., Hooper, D., & Murphey, T. (in progress). Students’ agency “action” loggings creates teacher efficacy. In P. Clements, A. Krause, & R. Gentry (Eds.), Teacher efficacy, learner agency. Tokyo: JALT.

Murphey, T. (1993). Why don’t teachers learn what learners learn? Taking the guesswork out with action logging. English Teaching Forum, 31(1), 6-10.

Mynard, J. (2019). Self-access learning and advising: Promoting language learner autonomy beyond the classroom. In H. Reinders, S. Ryan, & S. Nakamura (Eds.), Innovation in language teaching and learning: The case of Japan. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Porath, C. (2016). Mastering civility. New York, NY: Grand Central Publishing.

Reisinger, L. (2014). Using a bio-psycho-social approach for students with severe challenging behaviours. Learning Landscapes, 7(2), 259-270. doi:10.36510/learnland.v7i2.664

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2008). From ego depletion to vitality: Theory and findings concerning the facilitation of energy available to the self. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(2), 702-717. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00098.x

Sapolsky, T. (2017, April). Robert Sapolsky: The biology of our best and worst selves [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/robert_sapolsky_the_biology_of_our_best_and_worst_selves

I have long been interested in this kind of approach to education. Concern for a holistic view of each learner is valuable, and in my opinion, most valuable in the many schools in Japan facing recruitment crises, where they accept every applicant. Motivation and engagement are a much bigger problem in such schools, coming down to mere compliance. A greater number of students have problems that, as the authors point out, go far beyond not “exerting enough effort.” When I taught in schools like that, I found my role as a counselor took prominence over that of merely delivering content or setting up activities. I often used a kind of biopsychosocial model.

On the other hand, now that I am in a top-level school, where students are more self-directing, the need to watch their psychological condition (the ultimate outcome of the bio and social factors) is far less. However, having learned those skills in the previous schools I worked at, they are extremely valuable where I am now as well. Fewer students need interventions, but when they do, they are more likely to be missed by the system. I have heard other teaches dismiss students as “not trying hard enough” without realizing that the very ability to try hard is completely dependent on all the lower rungs of Maslow’s Hierarchy being clear. I often spot fires in those lower rungs, which give me a greater chance to accommodate our educational relationship. Parker Palmer discusses such views in his insightful “The Courage to Teach.” https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780787996864

All in all? Delightful!

One question fo the authors is their use of the word “sociologies” (ways of researching societies) as in learners “bringing the rest of their worlds to class with them through their biologies, psychologies, and sociologies.” Is this an error or done on purpose?

Thanks Curtis for your great review of the article and comments and question. For Tim, putting the word “sociology” in the plural helps people conceptualize the field as having many views rather than being one mighty explanation and interpretation and way of being in the world that we all necessarily agree on. I am aware that singular “sociology” is the study of the many contexts and that to some people it captures this diversity, but I fear to others it may seem like another dogma being passed down. I myself am discovering new ways of socializing and finding sociologies (Zoom) in this forever changing world. Thanks again for asking! Hope this is clear enough. cheers. Tim

Hi Tim & Curtis (Edlin),

Thank you for introducing your new approach ‘EcoEducational-BioPsychoSocial Model’ in promoting learner autonomy in language learning. It is a thought-provoking idea and I enjoyed reading your paper! I really wish to see this model in our everyday educational setting. With that thought in my mind, the following are my suggestions.

1. Definition of ‘EcoEducational-BioPsychoSocial Model’

You have mentioned that biological, psychological, and social context should be considered in education in order to focus more on learners’ holistic well-being. I believe this is something we really need to look at. You named it ‘EcoEducational-BioPsychoSocial Model’ which represents your concept. I hope this term will be used universally in the future! As I believe this is going to be one of the key issues in education, especially promoting learner autonomy, it would be nice if you had clearer theoretical underpinnings and definition for your ‘EcoEducational-BioPsychoSocial Model’. Although the definitions of BioPsychoSocial Model (Engel, 1977), Maslow’s hierarchy needs (1943), and the study of Hoshi and Kodama (2018) were introduced, I couldn’t find a citation for ‘ecology education’. Thus, it was a bit confusing to see the connection between Ecology education and BioPsychoSocial Model. In general, when we hear the word ‘ecology education’ we tend to imagine the study of relations between organisms and their environment. Smith & Williams (1999) mentioned in their book ‘Ecological Education in Action: On Weaving Education, Culture, and the Environment,’ that ecology education is ‘any learning experience that increases earth-literacy and earth-caring, rooted in earth bonding. This dimension of education is the primary way of preventing earth-alienation, the fundamental cause of destructive ecological lifestyles (p. 237).” If so, is ecology education part of the ‘society’ in BioPsychoSocial Model? How does ‘EcoEducational-‘ relate with or complement the BioPsychoSocial Model? Or does it refer to a different concept? I am very curious!

2. Well-being and autonomy

As you have mentioned, in recent years, the field of language learning psychology has increasingly focused on a more holistic and dynamic understanding of learner psychology. Similarly, well-being has become the focus of language teaching approaches (Gkonou, Tatzl, & Mercer, 2016; Ryan & Mercer, 2015). Well-being is considered more than only happiness; well-being means developing as a person, being fulfilled, and contributing to the community (Shah & Marks, 2004).

We intuitively know and understand that they are all related. However, how does ‘holistic well-being’ come into your “EcoEducational-BioPsychoSocial Model’? Is it part of psychology in BioPsychoSocial Model or is it a huge umbrella of the entire model? If you could conceptually make stronger links between ecology education, BioPsychoSocial Model, holistic well-being, and learner autonomy, I believe the term ‘EcoEducational-BioPsychoSocial Model’ will be well-understood. >Creating a concept map or diagram would help?

3. Teacher education

You mentioned that Tim has started to apply some activities to his class. I think it is a great experiment where students can benefit from reflecting themselves holistically. I know it is too early to mention in this stage and it is too much to include in your paper where you have a limited word count. However, I believe in order to realize your ‘Ecoeducational-BioPsychoSocial Model,’ teacher education is crucial. How can teachers learn and administer this concept? Especially, introducing biological approach in education sounds challenging. Should teachers collaborate with experts in biology? I would love to see your further research and experiment in this area!!

Thank you again for your innovative ideas. The above are just my thoughts and it doesn’t mean you have to make changes to your paper. Your paper just provoked my thought so much! I agree that it is time for us to broaden the scope of education. I am sure your paper will inspire many readers of this journal, and I sincerely hope you ‘make the world a better place!’

References

Gkonou, C., Tatzl, D. & Mercer, S. (2016). Conclusion. In Gkonou, C., Tatzl, D. & Mercer, S (Eds.), New Directions in Language Learning Psychology (pp. 249-255). Cham: Springer.

Ryan, S., & Mercer, S. (Eds). (2015). Psychology and language learning (Special issue). Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 5(2).

Shah, H., & Marks, N. (2004). A well-being manifesto for a flourishing society. New Economic Foundation, London.

Smith, G. A. & Williams, D. R. (1999). Ecological Education in Action: On Weaving Education, Culture, and the Environment, State University of New York Press, Albany.

Hi Satoko,

Thank you for your kind comments, helpful connections to other relevant areas, and productive questions. I’ll try to respond to each section in order. This is actually my second time writing this as my computer “helpfully” auto updated to give me the Microsoft Edge browser and lost my then nearly-completed document of responses.

1) While I think nature and the natural environment are certainly important for human health and flourishing, EcoEducational in this case does not refer to education about natural ecology. Rather, it is about using an ecological lens to better understand influence, opportunity, and action in the learning process, in the traditions of van Lier (2004), which was in turn influenced by , among others, Gibson (1986) and Eco (1979). It looks at potential for action or interaction, or affordance. In ecology, an affordance is emergent from the relationship between an organism and its environment and/or another organism in the environment. In our cases, this would be the learners and possibilities or opportunities for language learning and practice being afforded according to the [learning] environment they are in, including other learners. It is probably important to note that to be an affordance, one has to recognize it as an affordance (either to know or imagine how an opportunity exists or might be used). This is essentially where and how semiotics, or signs and making sense of them, comes into play. This noticing and resultant affordances can vary from learner to learner. If something is comprehensible to one learner but not another, for example, at that time it affords different things to the different learners. Essentially, the main point made by the inclusion of “eco” in the EcoEducational model is that learning does not happen away from context, and that context includes learning environments that students might be in, but the other environments and contexts in their lives, too. All learning happens embedded within a context, and each learner’s total personal context can be different. More recently, these concepts have become more commonly used as a lens for understanding autonomy and self-access, too (Menezes, 2011; Murray & Fujishima, 2016; Murray, Fujishima & Uzuka, 2014; Palfreyman, 2014).

2) Thank you for the papers you mentioned on well-being in language education. As mentioned, holism is dynamic and complex. To me, the ecoeducational-biopsychosocial model simply offers a structure to explore and explain some of the primary connections and considerations in this complexity. Thus, while it might not be exhaustive in detail, it can give a solid structure to identify the follies of an oversimplified view of education. In those terms, I think it can act as a sort of heuristic for understanding the place and reason for holism in education. For example, we can see that genetics can both influence and be impacted by physiological state (epigenetic changes via acetylation) which then in turn can influence biological development and structure; and that physiological states can influence hormones that alter brain function in various regions that affect attention, memory, and willpower; and that it can happen the other way, and psychological states can trigger, for example, the cascade of glucocorticoids that lead to a physiological stress response—one main culprit being cortisol. Then diet and sleep and exercise affect the balances and imbalances of hormones, too, which impact our neurology and thus our neuropsychology (with more prolonged stress, as the frontal cortex exerts less overall control, we may become less able to regulate effort, less able to focus, worse at memory recall, and have weaker imprints of new memories). Clearly this can affect learning. Lack of sleep can also affect the potentiation of memories that are meant to be reorganized in REM sleep. Irregular sleep, also, can affect circadian rhythm and natural rhythms of our hormones throughout the day (and thus, ability to focus well at certain times, sleep easily, etc.). Social health and interaction, too, influence our psychological health, and can elicit particular physiological responses, which then in turn, again, affect each other (in addition to possible support structures and motivating factors that can be afforded by a social context, as well as the scaffolding when learning something new that was the focus of SCT). Essentially, the takeaway is that everything is connected and can lead to cascading series of effects. Social factors affect both psychological and biological (physiological) factors (and vice versa), which then affect each other, etc. If we consider things from this perspective, internal and external contexts aside from or outside of the classroom collectively generate a massive impact on learning. Personally, for me, well-being is the point. But even for those whose ends is language skill instead of well-being, I hope that this model can show that well-being is STILL the optimal means to achieve those ends. Autonomy, it turns out, affects our types of motivations (think of SDT motivational types across scales of autonomy) and well-being. Autonomy and well-being in turn can both augment our ability to maintain long-term motivation and help avoid much of the pressure and stress people might feel in more controlled environments. Thus, I think there are strong connections to autonomy implied in this model. I hope to be able to explore this more in future writing. I hope to be able to more clearly illustrate the connections in the future (spoiler: everything is connected).

3) You were right about battling against a word count! I think that teacher education is an important road to explore, but something that I think will need to be addressed further in successive papers. Ultimately, I want students to have more control over themselves, and thus more autonomy. For this, they need to understand themselves. To this point, I think that applying this model will be most useful if some of it makes it out to the students themselves. If it stops at the teacher, it can engender some kindness and understanding and easier learning. As Robert Sapolsky, speaking about such complexity in regard to human behavior said, “It’s complicated… It’s complicated, so be damn sure you understand how things really work before you decide that you do and go and judge somebody, especially if you’re judging them harshly” (Arts & Ideas at the JCCSF, 2018). This perspective might help us to be more understanding or ask some questions to get a better sense of the environment and learners’ conditions. If we can help students to really understand, though, the point of sleep and diet and health and how these things can affect learning and performance; if we can help them understand how social health can affect their physical and psychological states and support their learning; if we can help them to understand the elements at play behind learning and skill development and human performance and health, and by understanding they can gain some control over themselves, I believe it will lead to more effective learning; it will lead to better skill development (language in our case) and performance; it will engender more autonomy, and more autonomous types of motivation (integrated and identified) are more likely to last long after the course is over. These elements together should also lead to healthier, more vital, flourishing outcomes, and ultimately a little better experience of the human existence for these students. The fact that a teacher, thus, is able to engender a greater effect and feel meaning and mastery is just icing on the cake.

So anyway, what I would like to see is some of this being included in teacher education. Even if they cannot remember specifics, it is important for them to understand that these factors are there and that they are important and related to the health and greater life experiences of students. Ideally, in the future, this would not be up to a single teacher, but become more integrated in the educational system as a whole—a kinder system that understands and supports, ultimately engendering more health and autonomy, better performance and outcomes, and less burnout. These days, there are so many free resources online around neuroscience, attention, hormone roles in the body, stress response, sleep, etc., including free courses via MOOCs and recorded lectures of classes from places like Stanford (an entire semester of lectures from one of Robert Sapolsky’s courses are available on YouTube). I would highly encourage anyone interested in the topic is simply start diving in and starting to make connections as you build out your knowledge (e.g. I know attention mediates noticing and memory formation, and activity in the frontal cortex mediates attention, but an active amygdala weakens control in the frontal cortex, and glucocorticoids like cortisol upregulate amygdala activity [and vice versa], and cortisol is higher in the stress response, and our body doesn’t differentiate between the type of stress, whether psychological or physical or from lack of sleep or inflammatory foods in our diet… that means these things are all mediating quality of learning, recall, and performance!). Again, it’s complicated, so don’t think we need to know everything or all the complexity immediately. Explore and learn something, then keep building on that. If we can incorporate this into teacher education in the future, the first step is producing buy-in, that teachers understand these things are important, and to extend some kindness and understanding to students (this is, perhaps, the main point of this model—to be able to clearly say that psychological health and state is important, social health and activity is important, physiological state and physical health are important, and context, too, all matters). From there, if we can understand it well enough to extend that knowledge to students so they can take control of these things themselves, their health and learning outcomes (and resultingly, we as a society) should become all the better for it.

All the best,

Curtis (Edlin)

References:

Arts & Ideas at the JCCSF. (2018, Feb 8). Robert Sapolsky [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/2bnSY4L3V8s

Eco, U. (1976). A theory of semiotics. Bloomington, IA: Indiana University Press.

Gibson, J.J. (1986). The ecological approach to visual perception. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Menezes, V. (2011). Affordances for language learning beyond the classroom. In P. Benson and H. Reinders (eds.), Beyond the language classroom. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Murray, G., & Fujishima, N. (2016). Social spaces for language learning: Stories from the LC. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Murray, G., Fujishima, N., & Uzuka, M. (2014). Semiotics of place: Autonomy and space. In G. Murray (ed.), Social dimensions of autonomy in language learning, Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Palfreyman, D. (2014). The ecology of learner autonomy. In G. Murray (ed.), Social dimensions of autonomy in language learning, Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Van Lier, L. (2004). The ecology and semiotics of language learning: A sociocultural perspective. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishing.