Emma Asta, Illinois Wesleyan University, USA

Jo Mynard, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan

Asta, E., & Mynard, J. (2018). Exploring basic psychological needs in a language learning center. Part 1: Conducting student interviews. Relay Journal, 1(2), 382-404. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010213

Download paginated PDF version

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

In this paper, the authors outline the initial stages of a research project designed to investigate the extent to which the Self-Access Learning Center (The SALC) at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) provides an autonomy-supportive environment conducive for effective language development. After giving a brief account of the context, the literature, and previous research, the authors discuss the aims of the project, provide a description of the research methods for the first portion of the research, and share some preliminary results. One of the unique features of this stage of the research project was that it involved a large number of co-researchers all of whom were active participants in the SALC at the time of the data collection. This paper gives details of the process of creating structured interview questions which were used to conduct over 100 interviews with regular SALC users. Limitations and next steps in the project are also provided.

Keywords: Self-determination theory, self-access, basic psychological needs, target language use, interviews, language policy, language conversation lounge, EFL

The project described in this paper starts with the basic premise that in order to learn a language, it is essential that students actually use the language that they are studying (Little, Dam & Legenhausen, 2017). In this study, we are concerned with the opportunities that learners have to interact in the target language (TL), in this case English, outside of class in a university self-access learning center in Japan. Providing a space for TL interaction is important, but we also need to investigate the extent to which learners feel inclined to actually use the TL in the designated space. This study explores the role of the physical self-access environment and the support structured within it in supporting learning and basic psychological needs (Deci & Ryan, 1985). There may be various motivational, psychological, social, and other factors that affect learners’ participation, or non participation, in English, and this paper provides background to the first portion of a study which involves multiple researchers in investigating students’ attitudes towards using English in a designated space. After briefly summarizing the literature, we will provide the outline of this portion of the study and details of the initial data collection period. Subsequent papers will present other aspects of the research and detailed results at various stages, but in this paper we focus on presenting some of the preliminary findings related to demographics and reported percentage of English use by participants.

Context

Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) is a small, private university established in 1987. It is located in Chiba, Japan and specialises in the teaching of foreign languages. While all students are majoring in foreign languages, every student, regardless of major, is enrolled in compulsory English classes as well. English language development is an important feature of the university, and the promotion of language learner autonomy is greatly valued. For these reasons, there has been a significant investment in supporting language development both inside the classroom and also outside the classroom in a large self-access learning center (The SALC). Self-access centers are “person-centred social learning environments that actively promote language learner autonomy both within and outside the space. Students are provided with support, resources, facilities, skills development, and opportunities for language study and use” (Mynard, 2016). The original SALC was created in 2001 and occupied two former classrooms. The second, much larger version of the SALC was built as a replacement in 2003 and operated successfully until 2017. This version of the SALC was an English-only space where students could choose to come if they wanted to be immersed in an English environment (SALC usage has always been optional). One of the features of the SALC specifically designed to provide opportunities for supported conversation in English is the English Lounge. This is a casual and comfortable space where students can interact in English with other students, both local and international, or with teachers on duty.

As the support services grew and self-access as a field evolved to accommodate more social learning opportunities, more space was needed in order for the SALC to continue to develop. In April 2017 a new building was completed called “KUIS 8”, which comprises of a two-storey SALC and 16 classrooms. The second floor contains the expanded English Lounge, among other English support services and learning spaces, and has been designated as an English only area. However, students may use any language on the the (larger) multilingual first floor. Research into language policy in SALCs is limited, and as Thornton (2018) writes, “factors governing policy choice are complex and depend on local context” (p. 156). The split-floor policy in the new SALC in KUIS 8 was intentional so that students could experience engaging in learning in an English-language environment (Gillies, 2010; Imamura, 2018). Alternatively, did not force students into an English-only environment if this made them feel anxious or uncomfortable (Imamura, 2018). The language policy was decided based on research conducted prior to the move to the new building and on research conducted in the first semester of 2017 (see Imamura, 2018 for a summary).

English Language Use in the SALC

One of the features of the KUIS campus since the 1990s is that students have had access to a space where they can be immersed in an English language environment. This continuity and the perceived value that students place on this space is one of the reasons that efforts have been made to maintain the English Lounge when we transitioned to the much larger SALC in 2017. However, it has become challenging to maintain an English language environment mainly because the increased floor space has meant that there is no longer an obvious language practice area as in the previous SALC. In addition, SALC staff offices are no longer next to the English practice area, so there are fewer opportunities for casual interactions in English, which had previously helped to maintain a natural English language environment.

Imamura (2018) describes several interventions that are currently being trialled in order to help students to develop an awareness of the languages they use and to provide opportunities for English practice. The purpose of these interventions is to bridge the gap between what the majority of students tell us that they would like (i.e., the provision of an English environment for the purpose of practicing English) and what tends to happen in reality (i.e., the majority of students use Japanese as a default language). Despite the interventions, the promotion of English on the second floor remains a challenge, and one of the aims of this project is to understand the reasons for this.

Before providing an overview of self-determination theory (SDT), which is the chosen theoretical model for understanding our context, it is useful to review some of the general reasons that English, or any foreign language use, seems to be challenging in Japan. Examining these underlying reasons could be key to understanding why Japan ranks low on global measures of English compared with neighbouring Asian countries.

Why do Our Students Find Learning English Challenging?

Although English language development is valued at KUIS, developing a competent level of English, particularly speaking skills, is a challenge for Japanese students for a number of reasons. Some of these reasons will be very briefly outlined below, but this is by no means a complete analysis of the complex factors affecting language learning.

Firstly we need to consider the differences in the languages and societal reasons. English is very different from Japanese, and learners perceive it to be difficult, which affects actual learning (Aida, 1994; Saito & Samimy, 1996). Secondly, Japanese is the dominant language used in society and daily life in Japan, and there are few opportunities for people to use English.

Other reasons relate to how languages are taught in schools. Firstly, there is not enough class time dedicated to the study and use of English (Aoki, 2017). In addition, teaching in schools tends to focus on grammatical accuracy and the development of reading and writing skills, rather than the development of practical communication skills. There is also generally a focus on accuracy (form) over fluency in schools, and much of this is driven by the aim to help students to do well in university entrance and other exams. In addition, although English language proficiency among teachers in schools is improving, it does not always reach government proficiency targets (Aoki, 2017).

Other reasons why learning foreign languages is challenging may stem from human psychology. The first example relates to perfectionism. Both self-oriented and socially-prescribed perfectionism are factors influencing emotional reactions to success and failure (Stoeber, Kobori, & Tanner, 2013). Perfection is a valued trait in Japanese society, which often means that people choose not to speak unless they are certain that what they say will be completely accurate. As second language (L2) use, including making mistakes in the L2, is essential for the development of language skills, avoiding using the target language because of the fear of making mistakes is detrimental for language learning. Another psychological dimension affecting language learning in Japan is related to language anxiety. Japanese learners of English tend to be anxious about speaking, and this is highlighted in a study by Williams and Andrade (2008) who found that 75% of the 243 Japanese students participants claimed that “output” activities in a foreign language were perceived to be anxiety inducing. One well-documented reason for this is that Japanese learners of English may fear negative evaluation (Kitano, 2002). In addition, students may be overly critical and self-conscious about their speaking abilities (Kitano, 2002). As Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope (1986) note, “performance in the L2 is likely to challenge an individual’s self-concept as a competent communicator and lead to reticence, self-consciousness, fear, or even panic” (p. 128). In short, language anxiety is likely to negatively affect L2 communication amongst Japanese learners of foreign languages.

This brief section is intended to give an overview to some of the factors that might be affecting our learners. Having a space such as the SALC on a university campus will not address all of these factors, but could provide opportunities for students to practice using the L2 in a safe and supportive environment. The purpose of this study is to evaluate whether we are providing the desired environment for our learners.

Theoretical Framework: Self-Determination Theory

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) was developed by Deci and Ryan (1985) and is a broad framework for the study of human motivation and personality. Within this broad framework, there are six mini theories. One of them is Basic Psychological Needs Theory (BPNT) which enables us to investigate what factors are needed in order to engage our learners in using English in the SALC environment. There are three important components to achieving basic psychological needs, which are: autonomy, relatedness and competence. Ryan and Deci (2017) liken the basic psychological needs to “nutrients that are essential for growth, integrity, and well-being” (Ryan & Deci, 2017, p. 10).

Autonomy

Autonomy is seen as the “need to be the origin of one’s behaviour. The inner endorsement of one’s thoughts (goals), feelings, and behaviors” (Reeve, 2016, p. 136). School-based research shows evidence that intrinsic motivation flourishes in autonomy-supportive classrooms where students’ opinions are valued, and where they feel a level of control and have opportunities to make choices in autonomy-supportive classrooms (Jang, Reeve, & Deci, 2010). This kind of research, to our knowledge, has not been attempted in a self-access environment.

Relatedness

Relatedness is the relationship that students have with their teachers and other learners and how socially connected they feel to others (How & Wang, 2016). It is also a state of caring for others and having this feeling reciprocated (How & Wang, 2016). One way that this relationship is enhanced is through regular interaction and communication and by creating opportunities for students to feel a sense of belonging, and also through giving students feedback. In a self-access context, a sense of relatedness is likely to be greatly enhanced if opportunities for regular interactions with others is facilitated through the design or programs on offer. Feedback may be more difficult to provide on a casual basis, but opportunities could be incorporated into classroom or homework activities that might take place in the SALC and discussed in class or in advising sessions. Relationships with other students is also important, and cooperative learning activities are linked with high degrees of self-determination motivation (Ntoumanis, 2001).

Competence

Competence is based on one’s perceptions of one’s own ability or one’s perceived self-efficacy (Bandura, 2009). Deci and Ryan (1995) suggest that the more competent someone perceives themselves to be, the more intrinsically motivated they will be. In a classroom environment, teachers can provide appropriately levelled tasks in order to facilitate a sense of competence, but this might be harder to achieve in a self-access environment. Instead, materials and activities might be graded and supported. In addition, self-access staff could help learners to establish appropriate goals in order to help them to experience success and feel competent.

Environment

Social context is also important for supporting BPNT by providing a “positive learning climate in which students are focused and motivated to learn” (How & Wang, 2016, p. 209, drawing on Evertson & Emmer, 1982). How and Wang (2016) argue that such an environment needs to have structure so that teachers can manage student behavior and develop systems for holding students accountable for their work, while showing students what to expect, which can enhance their sense of control (Blankenship, 2008). In a self-access context, care should be taken to establish self-access systems that facilitate a positive environment with some structure, but the structures should not be overly controlling.

SDT and self-access

Although there has been substantial research in different fields which draws on SDT and BPNT, such studies in language acquisition are rare, and studies specifically conducted in self-access contexts are, to our knowledge, non-existent at the time of writing. Some studies (e.g., Reeve, 2016) focus on classroom learning in general and investigate the extent to which a classroom environment is autonomy supportive or controlling. There are documented teacher interventions that can make an environment more autonomy supportive, such as promoting reciprocity between teachers and learners (Lee & Reeve, 2012), and other autonomy-supportive teacher behaviours such as these examples taken from Reeve (2016), Reeve (2009), and Reeve and Cheon (2014):

- Considering students’ perspectives

- Visualizing inner motivational resources of the learners

- Providing explanatory rationales for requests

- Acknowledging and accepting students’ expressions of negative affect

- Using non-pressuring language

- Displaying patience

We can also learn from studies conducted in learning environments that are not classrooms, for example, the context of a physical education learning environment (How & Wang, 2016) or a science laboratory (Sjöblom, Mälkki, Sandström, & Lonka, 2016). Whereas Sjöblom et al. (2016) focused specifically on the physical factors in the learning environment, our study investigated both the physical and human resources available to participants due to the nature of the self-access learning environment and of the language learning context. Many of the autonomy-supportive principles indicated in classrooms or other learning environments can be applied to a SALC. However, it is necessary to first consider students’ perspectives and attempt to understand their inner motivational resources and orientations, which is the rationale for beginning this study. Inner motivational resources (according to Reeve (2016) in a classroom environment) are the reasons why students engage in a lesson. The reason could be that the lesson is “need satisfying (inherently enjoyable), meaningful (important), goal relevant, curiosity-piquing, challenge inviting, etc.” (Reeve, 2016, p. 135). A self-access context by definition values self-direction as a starting point, but students also need to be able to exercise the agency required to initiate self-directed learning.

Research Aims

The overall study will draw on multiple data sources in order to evaluate whether the SALC is an autonomy-supportive learning environment that satisfies students’ basic psychological needs related to using English. The section of the research described in this paper will focus on learners’ needs and perceptions and is a starting point for further investigations. Therefore, the aims of this portion of the research are as follows:

- To understand students’ inner motivational resources by investigating reasons for coming to the SALC and for learning English

- To collect students’ views on whether we are creating suitable conditions (autonomy, competence, relatedness) to foster English language use in the SALC

- To understand students’ views on what the SALC team can do to further promote English

- To involve students as co-researchers ensuring that students are involved in the decisions relating to the SALC

- To raise awareness of the language aims of the SALC through the research process

The research questions that we developed for this portion of the research are:

- What are our students’ goals for learning English?

- Why do our students currently use the SALC?

- What are students’ views on using English in the SALC?

- How autonomy supportive do students perceive the SALC to be as a place to promote the use of English?

- What ideas do students have about the kind of support they need to use English?

This paper will give an overview of the methods for investigating these questions via interviews. Subsequent papers will focus on other research methods and detail findings and implications.

Methods

As one of the the aims of the project was to raise awareness of English language use through the research, we decided to conduct oral one-to-one, fairly structured interviews with random SALC users in English over a two-week period.

Interviewers

The SALC director, Jo (the second author of this paper), sent out a call for “expressions of interest” to join a research project via e-mail to all lecturers (learning advisors and teachers) who work in and around the SALC. Ten colleagues responded: five learning advisors who work full time in the SALC and five teachers who are on duty in the SALC twice per week. We held two meetings to discuss the research aims, process, and the content of the questionnaire. Later, we recruited six student researchers by personally approaching students we knew were regular attendees of the SALC who had often expressed an interest in promoting a stronger English speaking environment. One more intern also joined the research team.

Piloting interview questions

All research team members were included in the development of interview questions. The team started by identifying successful items that had been used in previous SALC research, such as questions from the annual Self-Access Learning Center (SALC) survey, in which we gather data related to students’ motives and perceptions. In addition, we formulated new items that attempted to address our research questions. After this process, we developed a pilot interview questionnaire, which we piloted the week prior to the two-week data collection period of the present study. Based on 13 students’ responses and input, questions were added, omitted, and modified. Also, throughout the week, research team members attempted iterations of the questionnaire themselves, gave feedback via a Google Document, e-mail, or in person, and suggested modifications to the researcher coordinating the interviews (Emma, an intern and the first author of this paper). Emma incorporated the suggestions and continued to revise and pilot the items until the questionnaire was ready to administer (Appendix 1).

Participants

We identified participants as any KUIS student present in the SALC during the two-week interview period was eligible to participate. All KUIS students study English as their major or as an additional foreign language. The majority of the local students at the university are undergraduates, normally aged between 18 and 22, are native speakers of Japanese, and have at least an intermediate proficiency level in English.

Interview guidelines

As our research team consisted of 19 interviewers (the SALC director, two interns, five learning advisors, five teachers, and six students), it was necessary to provide training to ensure some consistency of methods. Emma created an interview guidelines document (Appendix 2) that outlined the interview procedures and provided sample dialogues for interviewers to reference. She also created a sample interview video with the help of a SALC student worker for interviewers to watch.

Members of the research team conducted interviews with students in the SALC over a two-week period on weekdays during hours that the SALC was open (8:45-19:00). Interviews were conducted in English and took between 5 and 15 minutes to complete. We used an iPad to conduct the interviews and entered responses using Google Forms, but paper copies of the questionnaire available for those who did not have access to an iPad or preferred to write by hand. Interviewers were instructed to conduct the interviews in English. In cases where interviewees used Japanese in their responses, interviewers were encouraged to help them rephrase their responses in English or confirm the translation to English before inputting their responses. Interviewers were instructed to type open-ended responses verbatim.

In order to ensure random sampling, we recommended that interviewers vary the time of day and location of their interviews (first and second floor) and allow 20 minutes to complete two interviews (one on each floor). We also asked that they approach students studying independently, in pairs, and groups. However, when approaching groups of students, interviewers were to select one participant, as opposed to interviewing each individual in the group.

After confirming that a student had not previously participated in the study, the interviewers asked participants to read and agree to the terms and conditions of the interview. Interviewers then conducted the interview by asking the questions on the questionnaire and inputting the participant’s responses onto the paper copy of the questionnaire or into the iPad.

We conducted a total of 110 interviews (18 interviews using paper copies of the questionnaire), but only used 108 of the responses. One participant was eliminated because of an incomplete questionnaire (interviewer error) and another because the student was an international student whose first language language was English.

Preliminary Analysis

A detailed analysis involving all responses is in progress, but we will share some simple demographic information in this section drawing on the chart function within Google Sheets.

Who were the participants?

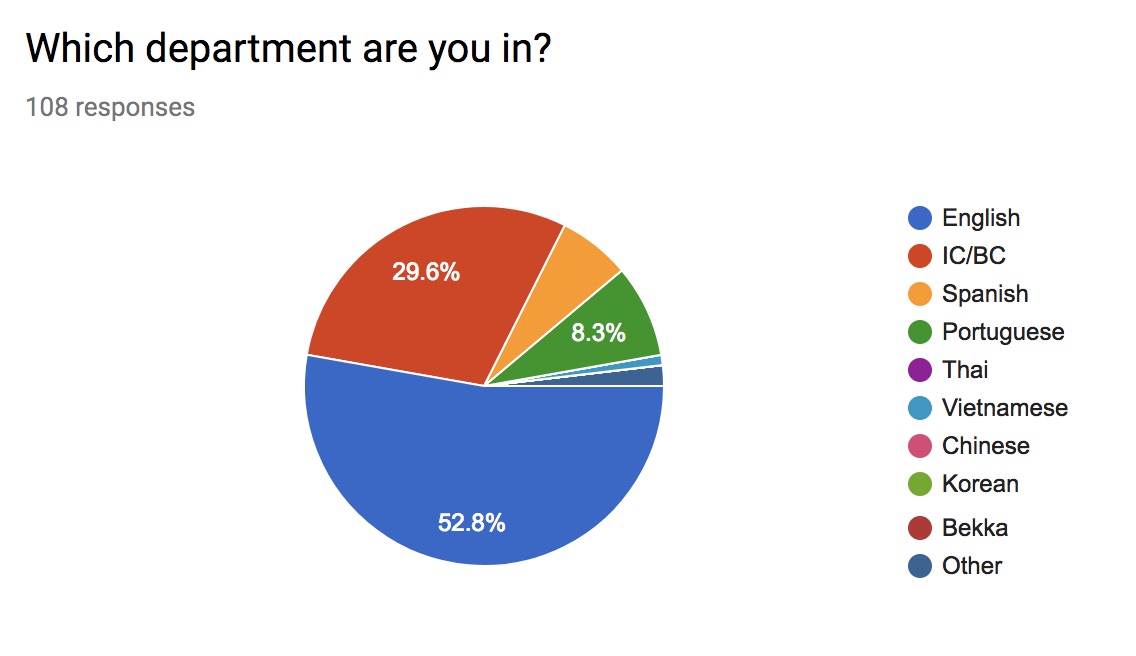

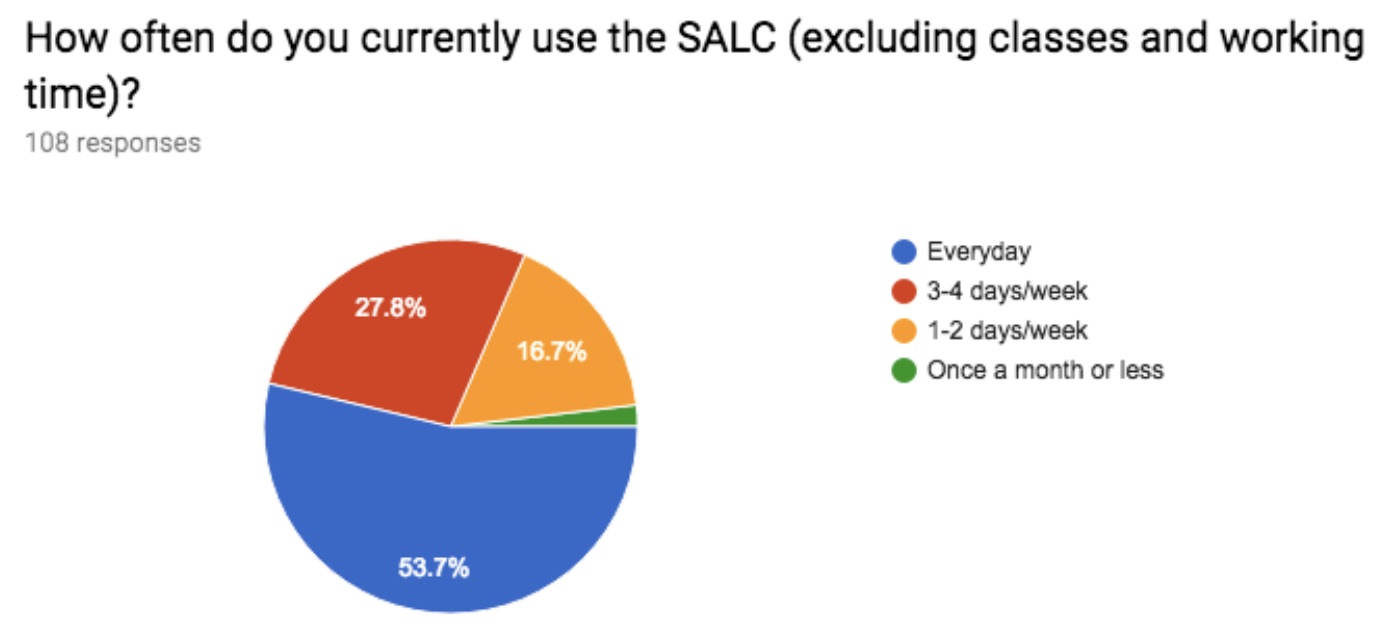

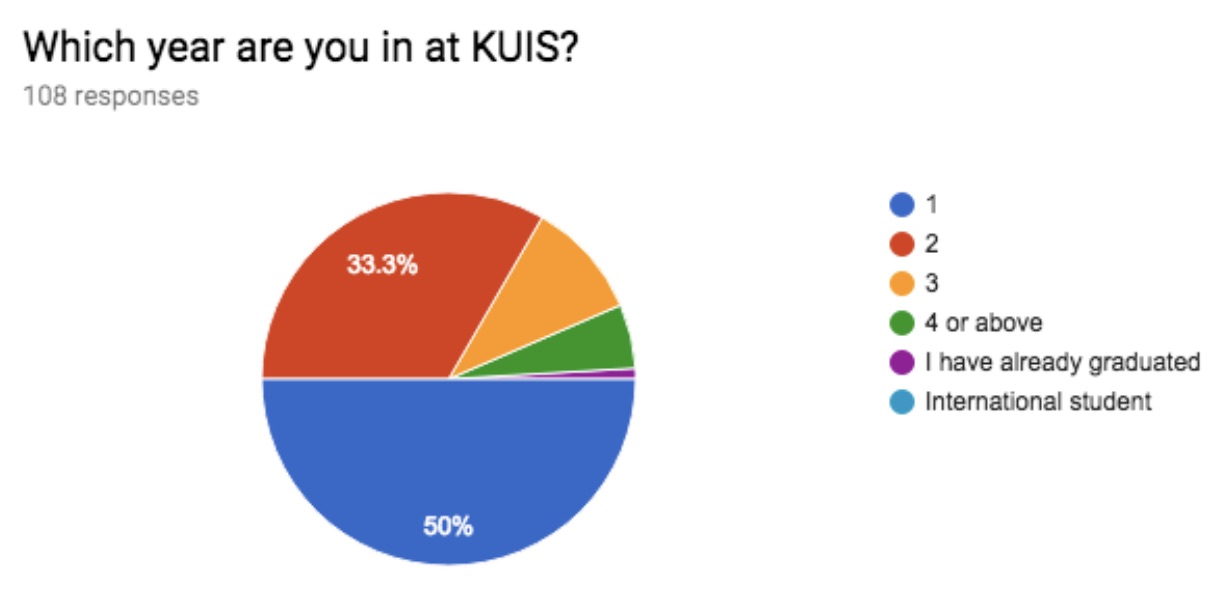

As Figure 1 shows, more than half of the participants were members of the English department majoring in English. Almost 30% were members of the International Communications or International Business Career major who also focus on English. 8.3% were Portuguese majors, 7% were Spanish majors, and the remaining students were members of other departments. As can be seen in Figure 2, 50% of the participants were freshman students, and 33% were sophomore students. The remaining students were in their third or fourth year. The majority of participants were regular SALC users, with more than 50% claiming to use the SALC everyday, and almost 30% using the SALC three to four times per week (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Participants’ Majors

Figure 1. Participants’ Majors

Figure 2. Participants’ Year at University

Figure 3. How Often do the Participants Use the SALC?

Figure 3. How Often do the Participants Use the SALC?

English use in the SALC

Participants were asked about the percentage of time they spent using English in the SALC. Responses ranged from 90% (1 participant) to 0% (1 participant) with the average being 40% of the time.

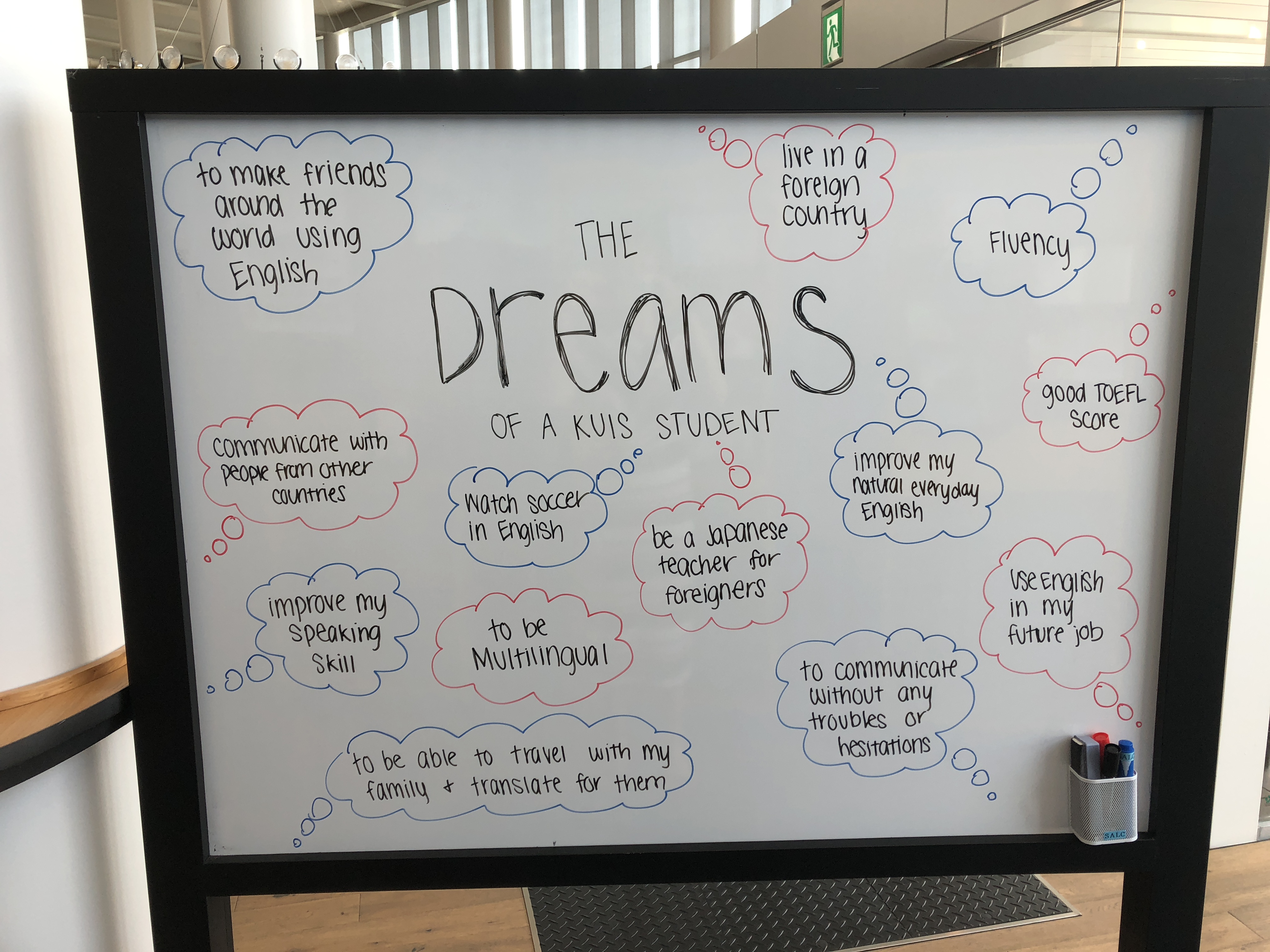

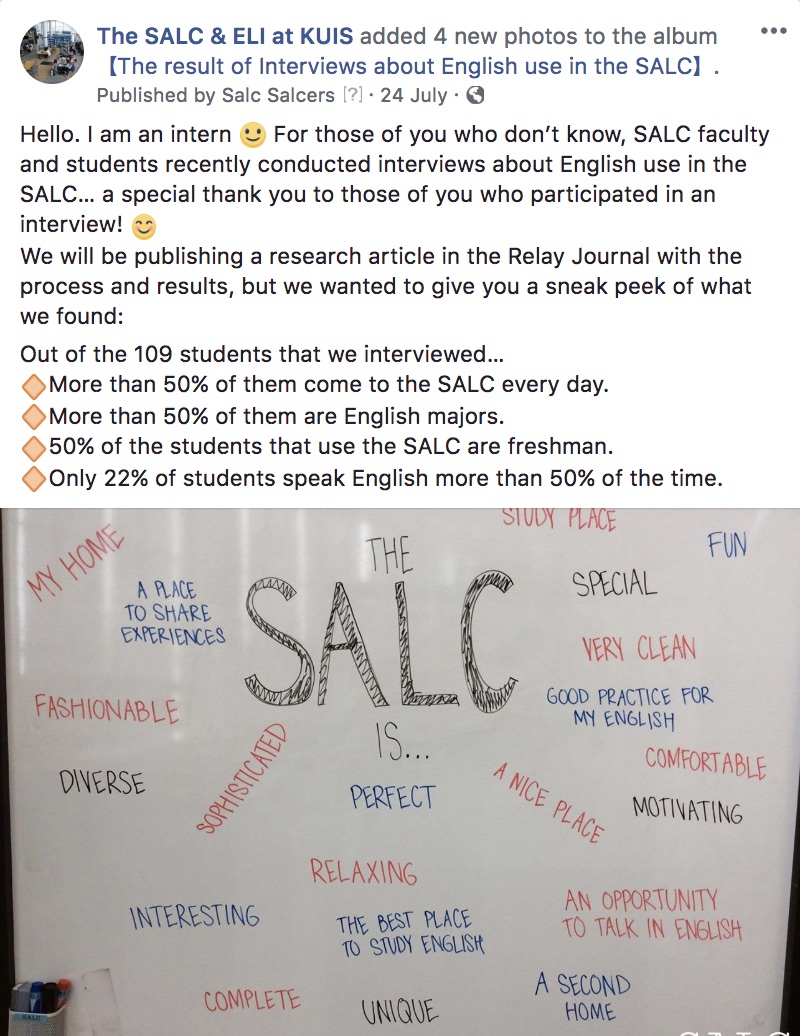

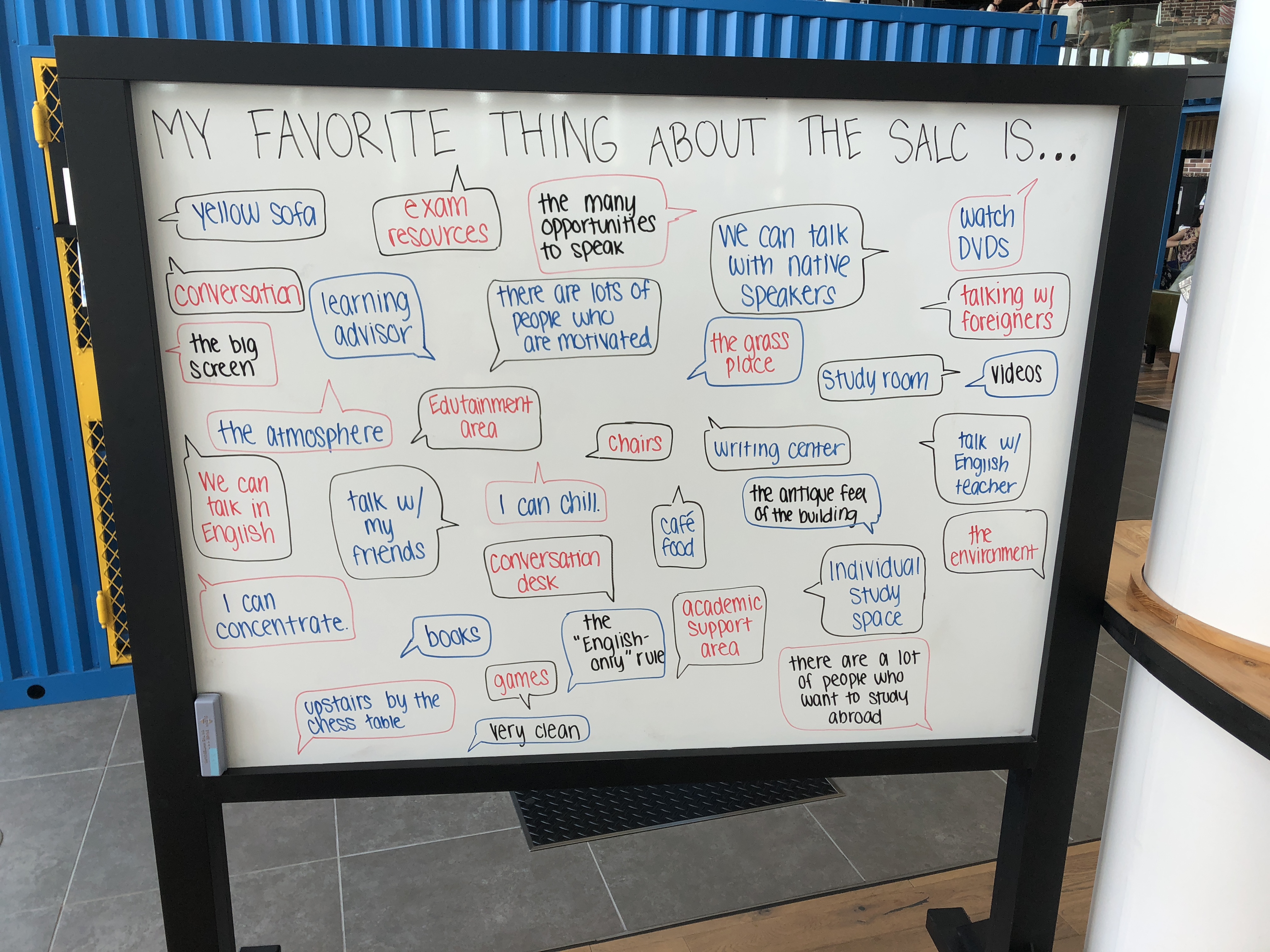

Sharing Findings with SALC Users

Although a detailed interpretative analysis is in progress, we shared a selection of preliminary data with students via two double-sided whiteboards inside the SALC (Figures 4a and 4b) and photos of the whiteboards and some of the results via social media (Figure 5). On these whiteboards, we included some of the demographic information as well as students’ answers to open-ended questions, such as “what is your favorite thing about the SALC?”, “Why are you learning English?” and “What is one of your personal language goals?”. The purpose of sharing these initial results was to involve the general population in the research at various times and also to perhaps allow them to be inspired by other students’ responses.

Figure 4a. Selected Responses to the Questions “Why are You Studying English” and “What is One of Your Personal Language Goals?”

Figure 4b. Selected Responses to the Question “What is Your Favorite Thing About the SALC?”

Figure 5. A Facebook Post to Share Some Preliminary Results With Students

Limitations

As with any interview-based study, there are a number of limitations in the present study. One limitation lies in the fact that there were nineteen interviewers on our research team. Although we held meetings to discuss the interviews, provided detailed guidelines (Appendix 2), and met with almost all of the interviewers individually, it was impossible to ensure that all researchers conducted their interviews in an identical manner. Additionally, the number of interviews conducted varied across interviewers (some team members conducted one interview, while others conducted more than ten). The interview lengths also varied depending on the interviewer. However, due to the mostly structured nature of the interview schedule, there was basic consistency in how the questions were phrased and ordered, and how responses were solicited.

Another potential limitation relates to the questions themselves. There are three identifiable limitations: 1) wording of the questions, 2) repetition across items, and 3) unnecessary questions. After piloting the questions and discussing them with other researchers, some questions still did not elicit responses that would answer our research questions. This may be due to the wording of the questions. For example, we asked students “What challenges or difficulties do you face when using English in the SALC?” as we were looking to identify areas of improvement for the SALC. However, many students answered with responses such as “Fluency” or “sometimes I can’t understand what teachers said.” This question provided us with useful information, but these were not the answers we were expecting. However, these responses do give us insights into the the perceived self-efficacy and perceived competence our students have of their English language abilities. This will no doubt inform our overall analysis of whether the SALC provides for basic psychological needs.

Furthermore, some questions may have overlapped, such as “What improvements can the SALC make to help you use English?” “What is your vision for the SALC? In a perfect world, what would the SALC look like? What is your “perfect SALC?” or “What would you change so that the SALC matches your vision?” Many of these questions provided us with identical information, making some of the additional question redundant.

Third, we included questions which provided little to no information, potentially making them unnecessary. For example, we first asked “What resources do you use in the SALC to help you use English?” We then asked a follow up question of “Are these resources useful for achieving your language goal?” This question had the potential to provide us with insightful information, but it is unlikely that participants would name resources they utilize and then tell us that they are not useful. More specifically, it is improbable that students utilize resources that do not benefit them, mention them in an interview.

The nature of our environment actively encourages the use of English. Consequently, the interviews were administered in English, which may have discouraged deep responses from students with lower English language proficiency.

Although we anticipated several of these unavoidable limitations, if we were to replicate this portion of the study, we would certainly make some modifications. Firstly, we would adjust some of the questions and conduct additional training in interviewing techniques to ensure greater consistency. Although the large number of researchers may have lead to some inconsistency in interviews, the benefits outweigh the disadvantages. For example, (1) having many interviewers meant that we could achieve our target of conducting more than 100 interviews; (2) the research included important stakeholders which may increase investment in further developing the learning environment; (3) the project benefited from multiple perspectives; (4) data analysis tasks could be divided up to make the project more manageable in the next stages; (5) and many follow-up action research interventions can be planned in smaller teams once the initial data have been analysed. The choice to administer the survey in English was intentional and despite the potential limitations, it is likely we would still do this in any similar studies due to the nature and purpose of the research.

Next Steps

The next steps involve an interpretative analysis of the interview responses by eleven of the researchers (all members of the academic staff) and findings will be reported in a follow-up paper. Based on these findings, the research team members will begin planning a series of action research projects or interventions in collaboration with students. These are likely to range from awareness-raising of language use, to modifications to the learning environment and services. The interview data alone is insufficient for answering the overarching question related to how autonomy supportive the SALC environment is and further data collection is needed. This will include the analysis of relevant items on the annual SALC survey administered to the larger university population at the end of July, 2018. Additional insights could be gained from a systematic audit of the SALC environment and services using an instrument designed to evaluate presence and degree of autonomy, competence and relatedness. We could also consider conducting focus-group interviews particularly targeting demographics not well represented in our other data.

Notes on the Contributors

Emma Asta is a senior at Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington, Illinois (United States), currently pursuing a major in psychology and minor in Hispanic Studies (Spanish). After her anticipated graduation in Spring 2019, she hopes to pursue a master’s degree in speech-language pathology.

Jo Mynard is a Professor in the English department, Director of the Self-Access Learning Center, and Director of the Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education at Kanda University of International Studies in Japan. She has an M.Phil. in Applied Linguistics from Trinity College, University of Dublin (Ireland) and an Ed.D. in TEFL from the University of Exeter (UK).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our research team members for ensuring that we achieved our target of more than 100 interviews and for all of the students who participated. Many thanks also go to our colleagues Scott Shelton-Strong, Isra Wongsarnpigoon, and Amelia Yarwood for their very helpful comments and suggestions on both the content and style of this paper.

Research Team Members: Emma Asta, Andy Gill, Yuri Imamura, Michelle Lees, Andria Lorentzen, Jo Mynard, Arthur Nguyen, Scott Shelton-Strong, Alecia Wallingford, Isra Wongsarnpigoon, and Amelia Yarwood.

Research Assistants: Daniela Gonzalez, Yasuhiko Haneda, Kokon Ikeda, Satoshi Kaneda, Nana Tomizawa, Mioka Nakamura, Sayaka

References

Aida, Y. (1994). Examination of Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope’s construct of foreign language anxiety: The case of students of Japanese. The Modern Language Journal, 78, 155-168.

Bandura, A. (2009). Cultivate self-efficacy for personal and organizationalÞffectiveness. In E.A. Locke (Ed,). Handbook of principles of organization behavior. (2nd Ed.), (pp. 179-200). New York: Wiley.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum.

Imamura, Y. (2018). Adopting and adapting to new language policies in a self-access centre in Japan. Relay Journal, 1(1), 197-208.

How, Y. M., & Wang, J. C. K. (2016). Creating an autonomy-supportive physical education (PE) learning environment. In w. C. Li, J. C. K. Wang & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Building autonomous learners (pp. 207-225). Singapore, Singapore: Springer.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. Modern Language Journal, 70, 125-132.

Jang, H., Reeve, J., & Deci, E. L. (2010). Engaging students in learning activities: It is not autonomy support or structure but autonomy support and structure. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102, 588-600.

Kitano, K. (2002). Anxiety in the college Japanese language classroom. Modern Language Journal, 85(4). 549-566. doi:10.1111/0026-7902.00125

Little, D., Dam, L., & Legenhausen, L. (2017). Language learner autonomy. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Mynard, J. (2016, August). Taking stock and moving forward: Future recommendations for the field of self-access learning. Presentation given at the 4th International Conference on Self-Access held at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City.

Ntoumanis, N. (2001). A self-determination approach to the understanding of motivation in physical education. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71, 225-242.

Reeve, J. (2009). Why teachers adopt a controlling motivating style toward students and how they can become more autonomy supportive. Educational Psychologist, 44, 159-178.

Reeve, J. (2016). Autonomy-supporting teaching: What it is and how to do it. In w. C. Li, J. C. K. Wang & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Building autonomous learners (pp. 129-152). Singapore, Singapore: Springer.

Reeve, J., & Cheon, H. S. (2014). An intervention-based program of research on teachers’ motivating styles. In S. Karabenick & T. Udan (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement (Vol. 18, pp 297-343). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Ryan, E. L., & Deci, R. M. (2017). Self-Determination Theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development and wellness. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Saito, Y., & Samimy, K. (1996). Foreign language anxiety and language performance: A study of learning anxiety in beginning, intermediate, and advanced-level college students of Japanese. Foreign Language Annals, 29, 239-251.

Stoeber, J., Kobori, O., & Tanner, Y. (2013). Perfectionism and self-conscious emotions in British and Japanese students: Predicting pride and embarrassment after success and failure. European Journal of Personality, 27, 59–70. doi:10.1002/per

Thornton, K. (2018). Language policy in non-classroom language learning spaces. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 9(2), 156-178.

Williams, K. E., & Andrade, M. R. (2008). Foreign language learning anxiety in Japanese EFL university classes: Causes, coping, and locus of control. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 5(2), 181-191.

Appendix 1: The Interview Schedule

Participant Background

- Which year are you in at KUIS? (closed-item)

- Which department are you in? (closed-item)

- How often do you currently use the SALC (excluding classes and working time)? (closed-item)

- What is your favorite thing about the SALC? (open question)

- What is the purpose of your visits to the SALC? Why do you come to the SALC?

- Do homework / projects for class

- Watch movies / dramas / TV / YouTube / etc.

- Communicate with people (ex. chat with friends, meet new people)

- Attend SALC events, communities, and workshops

- Meet learning advisors, teachers, and peer advisors (i.e. by appointment)

- Chat with learning advisors, teachers, and peer advisors (i.e. informal yellow sofa conversation)

- Eat lunch / relax / play games

- I work / volunteer in the SALC

- Practice English

- Modules / self-study

- Other (open response)

Language Goals

- Why are you studying English?

- Because I have to / it’s an obligation

- It is useful for my future job

- I want to communicate with foreign people

- I want to travel

- I want to live in another country

- I like movies and music that are in English

- I want to study abroad

- Other (open response)

- What is one of your personal language goals? (open question)

- What resources do you use in the SALC to help you use English (ex. people, places, materials, equipment, events, etc.)? (open question)

- Are these resources useful for achieving your language goal?

- Yes

- No

English use

- On average, what percentage of the time do you use English in the SALC (excluding classes and working time)? (scale from 0% (never) to 100% (always) in 10% increments)

- Who do you enjoy speaking English with the most in the SALC?

- Teachers

- Learning advisors

- International students

- SALC student staff and community leaders

- Classmates and other KUIS students

- Friends

- Other Native English speakers

- I don’t want to use English

- Why do you enjoy speaking with them? (open question)

- What challenges or difficulties do you face when using English in the SALC? (open question)

- What improvements can the SALC make to help you use English? (open question)

Future Directions

- What is your vision for the SALC? In a perfect world, what would the SALC look like? What is your “perfect SALC?” (open question)

- What would you change so that the SALC matches your vision? (open question)

Appendix 2. Interview Guidelines for Researchers

Interview Guidelines

There are many people conducting the interviews (teachers, learning advisors, students) and it is important to maintain consistency across interviews. Please adhere to these guidelines as you conduct your interviews, and feel free to reference this or the sample interview video if you are unsure about anything.

ACCESSING THE QUESTIONNAIRE:

- Open the Google form titled “Official Questionnaire.”

- Click the eye icon in the top right corner labeled “Preview” to open a blank survey.

- For those of you (interviewers) who would like to fill out the questionnaire by hand, there are copies located at The SALC Counter. Please put completed handwritten surveys in the envelope at The SALC Counter.

- When using the iPad, you can fix typos later by accessing the spreadsheet.

POLICIES:

- Data collection will go from Monday, July 9 until Friday, July 20.

- All interviews must be conducted IN THE SALC.

- Use an iPad to conduct all interviews.

- Conduct interviews in English. For students who use Japanese within the interview, encourage them to rephrase their responses in English and assist with accurate translation.

- Type answers verbatim, or as close as possible.

- Complete the interview information before submitting the form.

CHOOSING YOUR PARTICIPANTS:

- To improve random sampling, vary where you conduct your interviews (conduct interviews on both floors of the SALC).

- If you approach a group of students, select one student to participate in the interview. Others can be interviewed on a different day or by a different interviewer.

- Approach students studying independently and in groups.

HELPFUL TIPS:

- If possible, give yourself 20 minutes to complete two interviews (one on each floor).

- Try to conduct interviews at different times of the day.

- Maintain consistency across the interviews that you conduct.

- Keep in mind that each questionnaire should take 5-10 minutes to complete.

CONDUCTING AN INTERVIEW:

Here is a suggested way to approach a potential participant:

“Hi, my name is [your name]. We are conducting a survey about English use in the SALC and I wanted to know if you would be willing to participate.”

- If they are willing to participate, ask them whether they have been interviewed before.

- If they have not been interviewed, inform them that it will take 5-10 minutes and will be conducted in English.

As mentioned before, it is extremely important to maintain consistency across interviews. One of the best ways to do this is to ensure that interviewers are asking the questions in the same way across interviews.

- You want to maximize the amount of information that you’re receiving from a participant, while ensuring that the information they are providing accurately represents their attitudes and behaviors. Be aware of when and how often you are asking follow-up questions.

- There may be awkward or long pauses while participants are thinking and formulating their answers. Avoid asking questions during this time, as this may interrupt their thought processes or influence their responses.

Here are some sample dialogues and guidelines for specific questions:

Question: How often do you currently use the SALC (excluding classes and working time)?

This question aims to determine how many DAYS a participant comes to the SALC, not how many individual times a day. For example, if a participant comes to the SALC three times a day, 3 days a week, you would record their answer as “3-4 days a week.”

Question: What is your favorite thing about the SALC?

Possible response: Learning advisors.

Here, it is OK to ask a follow-up question, such as “Why?” “Can you tell me why you think that?” or “Anything else?” to obtain more information.

Better response: Learning advisors; when I was a freshman and sophomore, I often talk with LA and it was so good.

Question: What is the purpose of your visits to the SALC? Why do you come to the SALC?

The difference between “meet with learning advisors, teachers, and peer advisors” and “chat with learning advisors, teachers, and peer advisors” is the level of formality. “Meeting” refers to appointments in the conversation area or academic support area, whereas “chatting” refers to more informal conversations (ex. Yellow sofa).

Question: What resources do you use in the SALC to help you use English (ex. people, places, materials, equipment, events, etc.)?

Start by asking the question by itself. If students seem unsure or confused, it is OK to prompt them with the text in the parentheses.

Question: What is your vision for the SALC? In a perfect world, what would the SALC look like? What is your “perfect SALC?”

For this item, ask all 3 individual questions. They are measuring the same hypothetical construct, but it may be helpful to provide alternate phrasing. One may be easier for a participant to respond to or understand.

Question: What is the purpose of your visits to the SALC?

Question: Why do you want to learn English?

Question: Who would you like to use English with?

For these types of questions, let the participant provide their own answer(s) before you prompt them or provide them with some suggestions.

My first impression of this paper is that this is an original and potentially valuable study, which will likely be used as a reference point for those who wish to replicate similar undertakings in self-access centres in other contexts. And as such, it is a welcome addition to the growing literature as regards self-access. By using self-determination theory as its theoretical framework to research the effectiveness of the learning environment of the KUIS SALC, it sets off into somewhat uncharted territory, and in this way demonstrates the writers’ determination to develop new vistas of what autonomy-supportive environments might need to consider when making changes in design or services to ensure effectiveness. I would say you have conveyed the purposes and the rationale underpinning the study convincingly, quite thoroughly and with clarity.

I must also say that the detail you have used to describe your methods is clear and useful, and I think will be inspiring to readers who may want to try to set up a similar ‘all-inclusive’ approach to evaluating a similar environment. As I was involved in conducting a few of these interviews, I can vouch for the transparency of the interviewing process, but can also relate to some of the misgivings expressed in the limitations section.

This final section of the paper (limitations), left me as a reader wondering at the length of it, which apart from a few notes I’ve included on the Word document for your consideration, may be one of the few weaknesses of this paper, in my view. Recognition of limitations is of course crucial for working through them and necessary as a part of any reported study. However, would it be helpful to shorten this section so that the main points are conveyed, but leaving out some of the detailed descriptions that may be of more interest to the research team, but less so to the reader? This is just a thought of course, and you may have specific reasons for including such detail here.

As a snapshot of an ongoing project with several different strands, I think you have done an excellent job of setting the background for the next steps, and having done much of the ‘heavy-lifting’ have set a good standard for those who will follow on.

I agree with your suggestion for including focus-groups as part of your ‘next steps’, particularly to include, as you say, demographics not well represented, but also to give real voice to help balance out the surveys, which as you have also detailed, were subject to several limiting circumstances. By providing students with an alternative venue for self-expression, it could be a very interesting chance to consolidate and expand on your preliminary findings from the interviews.

On the whole, I very much enjoyed reading this article and as I have said, believe it to have real potential as a ground-breaking pilot, which others in the field may find very useful as a practical reference (as a study to replicate in some way). Its value as a theoretical reference applicable to similar fields is also clear, and I am sure will be welcomed by other readers outside of self-access.

A job well done (!) on conveying with such thoroughness and clarity the foundation you have laid for the ongoing project of evaluating the autonomy-supportive environment of this self-access centre.

Dear Scott,

Thank you so much for your positive feedback and very useful comments! We are definitely attempting to do something new by drawing on self-determination theory when looking critically at a self-access learning centre environment. We are not able to fully comment on whether our SALC is an autonomy-supportive environment from the interview data alone, but we felt it would be a useful exercise to at least lay out the foundations of what we hope will be a series of papers that might eventually lead us to some answers and recommendations. We went into some detail about our research methods here as we had the luxury of space. Our aim was to be transparent and document our process thoroughly for ourselves, but also perhaps for other colleagues who might want to replicate the study. Of course, as you noted, we went into unusually lengthy detail with our limitations too due to the luxury of space. Thank you for giving us a reader’s perspective on this and we have decided to cut down this section in the final version. Actually, we have already done so and it does improve the paper. We appreciated your pointing it out.

Thanks again for taking the time to read and comment on the paper. Your feedback and comments on the text have definitely helped us to improve it.

With appreciation,

Emma and Jo