Jo Mynard and Kie Yamamoto, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan

Mynard, J., & Yamamoto, K. (2018). User perceptions of an app for managing self-directed language learning. Relay Journal, 1(2), 405-428. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010214

Download paginated PDF version

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

In this paper, the researchers report on a study which is one part of an evaluation of a purpose-built app intended to support students’ self-directed language learning as part of a course of study. The app was used by Japanese learners of English for two years and was created in order to enhance and possibly eventually replace the paper-based materials that had been used for more than ten years. In this paper, the researchers present the findings from the research investigating learner and educator perceptions. As the ultimate purpose of the research was to be able to make informed decisions about the future use of the app, it was vital that these voices be included in the process. The findings indicate some benefits, but mostly limitations of the app and suggest ways in which future tools for managing self-directed learning be optimised.

Keywords: self-directed language learning, app, evaluation, user perceptions, self-directed learning,

In this paper, the authors investigate an intervention that aimed to enhance learning by drawing upon technology in order to promote language learner autonomy. Specifically, the purpose-built iPad app was designed to enhance an established course which uses paper-based materials to raise awareness of self-directed language learning skills and promote learner self-management.

Technology has featured in the autonomy literature for several decades (Reinders & White, 2016), and some work has been done on investigating how learners can be supported in managing their learning with the help of technology (e.g. Reinders, 2007). However, with the development of the idea of learning as an ecology (Benson, 2011a) where learners draw upon multiple environments as backdrops to the development of language and autonomy, mobile apps in particular play and increasing role. In addition, we now know more about the importance of social technologies in the development of language learning and autonomy (Lamy & Mangenot, 2013).

Fostering learner autonomy is a widely-accepted goal of language education so that learners take charge of the process rather than rely on teachers and classes as they learn languages through their lives. Learner autonomy is a multifaceted concept entailing a level of awareness and control over cognitive, metacognitive and affective aspects over one’s learning (Benson, 2011b). Autonomous learners need to be able to manage many aspects of their learning such as analysing their needs, setting goals, choosing appropriate resources and strategies, implementing a plan over study over time, and evaluating language gain.

As part of an ongoing action research project, the authors and other colleagues at their institution have been engaged in enhancing ways in which learners are supported in developing awareness and control over language learning in a self-access context. The research described in this paper takes place in a self-access learning center (The SALC) at a small private university in Japan specialising in foreign languages. A team of eleven learning advisors (henceforth advisors) work with learners outside the classroom on personal aspects of their learning in a process known as advising. Advising in language learning (ALL) is an approach to promoting deep reflection on learning and developing learner autonomy through one-to-one dialogue (Kato & Mynard, 2015; Mynard & Carson, 2012). Advising happens in various forms, e.g. in a face-to-face advising session, through ongoing written feedback which focuses on promoting reflection through dialogue, during casual in-person micro advising sessions in the SALC (Shibata, 2012), and during class workshops related to learner autonomy. One of the principal ways in which advisors at the authors’ institution work with students is through somewhat structured self-directed learning course which will be explained in the next section.

The authors and their colleagues have been influenced by sociocultural views of learning, and draw on Transformation Theory (Mezirow, 1991) in their practice. Transformational learning, according to Mezirow (1991) is mediated by discourse and reflection and results in a shifting worldview. Transformational dialogue is particularly valued in the authors’ context as part of the well-developed advising programme to support learners’ out of class learning.

Self-Directed Language Learning (SDLL) Modules and Courses

Self-directed language learning (SDLL) (Dickinson, 1987; 1995; Morrison, 2013; Murray, 2004) draws upon the broader field of self-directed learning (SDL) which is a humanistic approach to learning originating from earlier work by Knowles (1975). SDL in an adult education context is “designed to help adults learn how to make their own decisions in accomplishing personal learning goals” (Hiemstra, 2013, p. 24). SDLL adapts this goal to the field of language learning and is commonly introduced to learners as a series of cognitive, metacognitive, and affective skills, as well as skills necessary to become a lifelong learner. A knowledge and sense of control over these are key skills can contribute to language learner autonomy (Curry, Mynard, Noguchi, & Watkins, 2017).

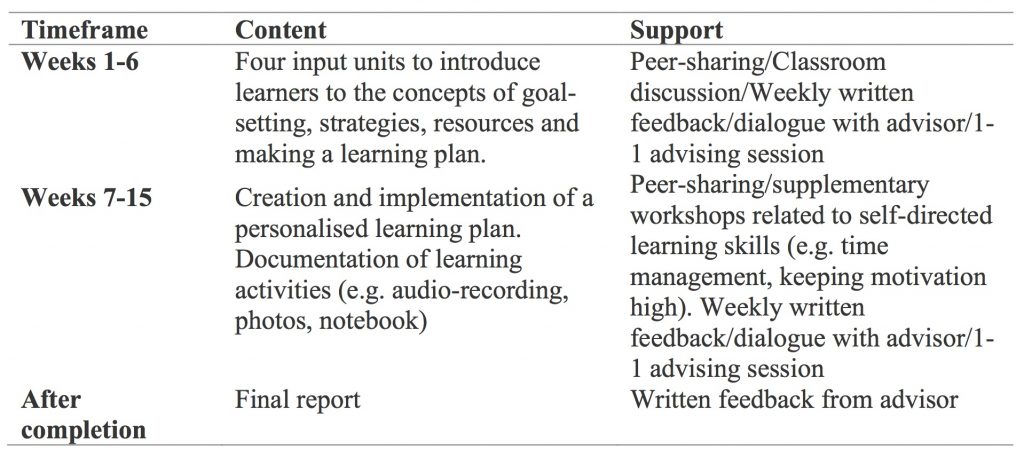

Self-directed learning training has been offered by the institution in various forms since the SALC opened in 2001. Providing training in self-directed learning is an essential component of the SALC as learners entering the university tend to have little experience with learning autonomously or acting upon their own volition. Self-directed learning training was first established in the form of a module, which allows learners to focus on their own needs and goals by working with their learning advisors independently. This program has been improved and developed over time with input from generations of students and advisors (see Mynard & Stevenson, 2017 for an overview). In 2011, the advisor team undertook a curriculum evaluation (Thornton, 2013) and, after a fairly substantial overhaul, the modules were re-launched in 2014 and renamed Effective Learning Module 1 (ELM 1) and Effective Learning Module 2 (ELM 2). In addition to these self-paced modules, credit courses on SDLL had been offered for several years. As part of the curriculum reform, these courses were streamlined, coordinated and re-launched in 2014. The courses are known as Effective Language Learning Course 1 (ELLC 1) and Effective Language Learning Course 2 (ELLC 2) and contain the same content as the modules. The difference between modules and courses at the time of this study were that (1) the modules were not offered for credit, (2) the classes lasted for 15 weeks and the modules lasted for 8 weeks, (3) the classes met weekly and were facilitated in-person by an advisor whereas the modules were self-paced and communication between advisors and students was normally in written form. The structure of ELLC 1 is shown in Table 1. ELLC 2 consists of a longer implementation period without input units, but an orientation and refresher of the terminology was included. The structure is the same for ELLC 1, but the timeframe was adjusted to fit a 15-week course giving a longer implementation period and time for preparation of the final report.

Table 1. Structure of the ELLC 1 Course

Development of the App

Paper versions of the materials for both the modules and the courses had been used successfully since 2003. However, an app version was developed due to a desire to investigate and capitalise on the opportunities afforded by technology to enhance self-directed learning beyond the physical boundary using technology. In addition, an opportunity for research into a new approach presented itself as new freshman students from 2014 onwards were all asked to purchase ipads. It was also hoped that an app version of the materials would include a management system which could help the team to document, understand and monitor the module processes more efficiently than the manual version that had previously been employed. With around 400 students engaged in one of the SALC’s courses or modules each year, a management system is crucial for maintaining the quality of advisors’ feedback, making the feedback process more efficient, leaving more time to work with students and continue to improve the service to them.

Although numerous apps already exist for aspects of language study, for example, helping learners to build vocabulary, prepare for tests, or increase their reading speed, there were no apps available for managing one’s self-directed language learning. The team realised that there was a need for such an app so an app development company was employed to create the app version of the module materials. The advisor team shared their vision of how the app could operate by examining existing apps (language learning and general), drawing on the Framework-for-Action (FFA) model developed by Hughes et al. (2011). The FFA model incorporates the components pf replacement, Amplification, and Transformation which will be described briefly in the next section.

Replacement

This largely involves simply replicating print materials in digital form. The team ideally wanted to go beyond simple replication, although understood that some materials may not go beyond replacement in the first iteration of the app. However, digital replacement has the benefit of being simple to distribute to students while saving paper and helping students to document and organise their work in one place.

Amplification

Amplification enhances learning opportunities due to certain affordances offered by technology. For example, the team hoped to include interactive visual tools which would help students to visualise their learning progress. In addition, the materials could be amplified by allowing responses to be shared with others, and also a system to allow learners to keep track their own progress.

Transformation

Transformation indicates a deeper understanding and may incorporate shifts in beliefs about learning. Although the team realised that the first iteration of the app may not necessarily promote transformation in learning, they wanted to incorporate some features which might contribute towards some transformative moments. For example, a smooth communication system between learners and their learning advisors and also learners and other learners was desirable to facilitate reflective dialogue that can lead to transformative moments (Kato & Mynard, 2015). In addition, technology allows for materials to be available in a variety of modes such as audio, text and video which may appeal to different learners and provide access to a range of ideas and ways of thinking. Finally, a feature enabling students to document their activities and reflections on learning in a variety of ways, e.g. audio, video, text, photos, would facilitate re-organisation of knowledge leading to possible transformative moments.

The app developers worked closely with members of the advisor team until the app was ready to pilot and finally introduce to students, providing the materials for SDLL courses and modules.

The Study

Methodology

This part of the larger study is an interpretative project designed to investigate participants’ experiences and perceptions of first-hand use of the app. An action research framework was used to guide the ongoing project.

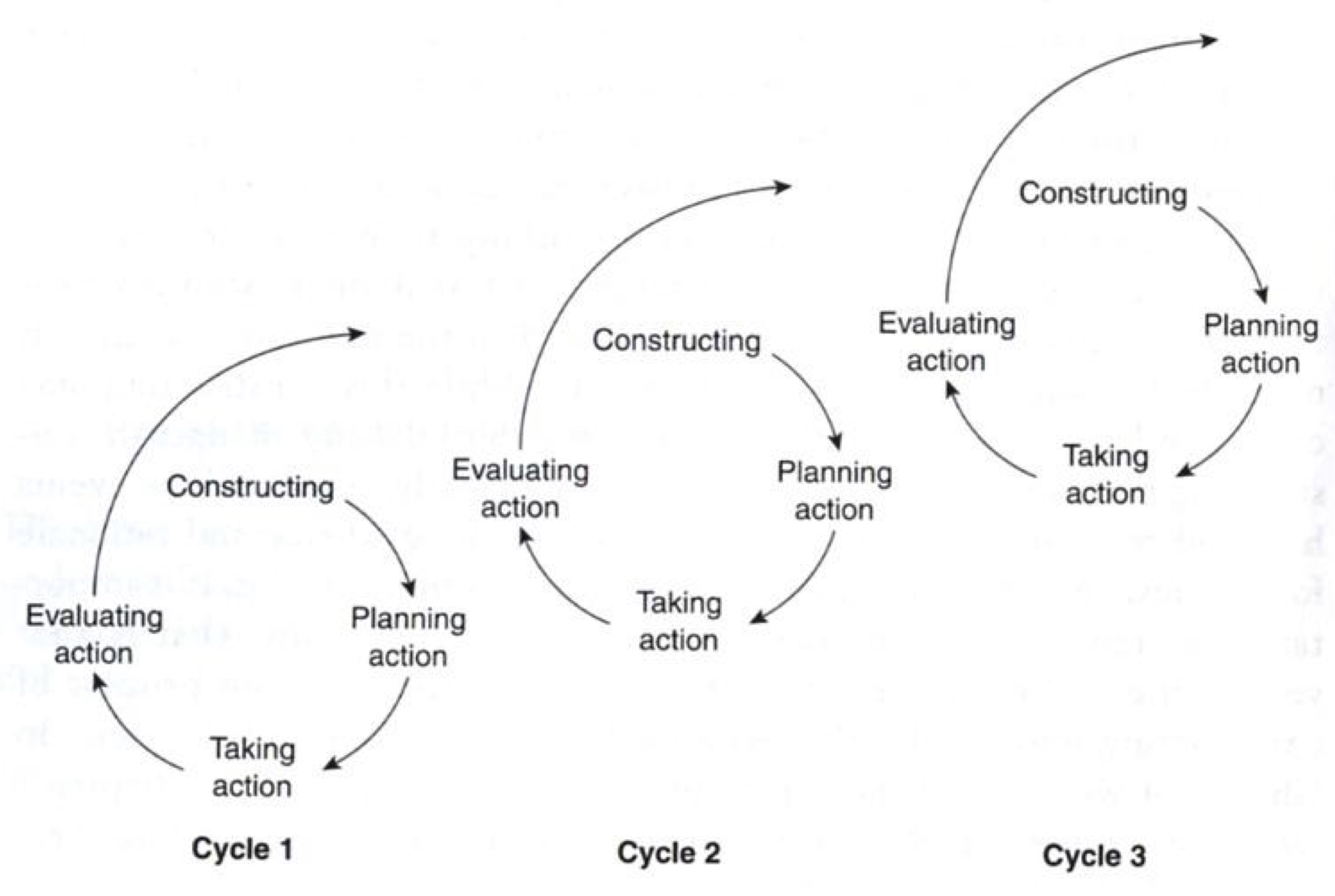

The project was the second cycle in an ongoing action research project which aims to systematically collect and analyse data, make ongoing observations, and make changes as needed for the benefit of learners at the institution. The SALC team are drawing upon Coghlan and Brannick’s (2010) cyclical model of action research to guide the process (Figure 1). Within this model, the research is made more manageable as each cycle informs the next one. The overall aim of the project is to create a tool (e.g. app) which is easy to use, promotes SDLL, and fosters transformative learning. The assumption being that at various stages, either the app will be revised or new tools created to gradually increase levels of ‘amplification’ and ‘transformation’ as described in the FFA (Hughes et al., 2011).

Figure 1. Cycles of Action Research (Coghlan & Brannick, 2010, p. 10)

In an earlier paper published by members of the SALC team (Lammons, Momata, Mynard, Noguchi, & Watkins, 2015), a brief report on the pilot process was presented. This portion of the research was considered to be “Cycle 1” in Figure 1. In the present paper, the researchers are operating within Cycle 2 which incorporates research conducted between April 2015 and July 2016; approximately three semesters.

Purpose of the present research

The purpose of the research in Cycle 2 is to evaluate the app in use by a larger group of students in order to make a decision about future continued app use. From a pedagogical perspective, it was hoped that the research could shed light on the benefits of technology designed to facilitate the learning process. The ultimate aim is to develop a tool that promotes transformative learning while also offering an efficient management system that improves the kind of support that advisors can give. Although the assumption was that the current app does not fully achieve these two roles, it is an important step in the process of discovering which features a tool needs to possess to facilitate deeper level learning and better level of support. There was also an important practical element to the research; results would help the SALC to justify decisions to either continue or discontinue the app, and possibly to justify further investment in a self-directed learning app.

Research questions

- What are advisors’ views on learning benefits facilitated by the app?

- What features would learning advisors like to see on the app in general?

- What kind of influence did the students perceive that the app had on their learning?

- What features would students like to include in a future learning tool?

Methods

Advisors’ perceptions

Advisor input has been incorporated into the ongoing app development process from the beginning, but this research aimed to investigate the advisors’ perceptions once they were actually using the app with (on average) around 20 learners each. In the first semester, all of the advisors had agreed to use the app with their students. Advisor perceptions were sought by means of a focus group discussion facilitated the researchers held in June 2016 which was around the midpoint in the semester. A focus group discussion is a “carefully planned discussion designed to obtain perceptions on a defined area of interest in a permissive non-threatening environment” (Krueger, 1994, p. 6). A focus group discussion was deemed to be the most appropriate method for understanding how advisors used and perceived the app as the group are accustomed to having open and frank discussions during the weekly meetings and has been a successful research method in the past (e.g. Thornton, 2013). Although the researchers moderated the discussions, the purpose of the discussion would influence the ways in which learners were supported, so the advisors were invested in the process in order to ensure the best future outcome. After the discussion, notes were organised into points and the researchers shared their interpretations with the participants (who agreed for the data to be used in this paper). The advisors were encouraged to add comments or additional notes and reminded of this again at the end of the semester. All of the advisors were given the option to use the app again in their semester 2 classes, but none of them chose to do so.

Learners’ perceptions

In order to be able to have enough students using the app to provide data for evaluation purposes, it was decided that data generated from app use within a credit course (ELLC 1) between April and July 2016 would be used. However, as the app was originally designed for outside class use, some aspects of the evaluation related to independent use would still need further investigation. Nevertheless, it was at least possible to gather the perceptions from a larger group of participants. Although more than 100 students also began to use the app to study independently, for practical purposes, only ELLC 1 students were included in the study as all of them would use the app for the entire semester and complete it at the same time.

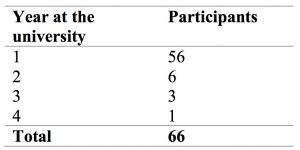

The app was used by 84 students (three classes) taking ELLC 1. It should be pointed out here, that all of the advisors supplemented the app in various ways either by providing some paper-based class activities, creating a shared folder to distribute additional materials, or by using Google+ to enhance the opportunities for communicating with individual students. At the end of the course, the students also completed an online course evaluation questionnaire and 66 students gave permission for their responses to be used in the study. A summary of the participants by year at the university is shown in Table 2. The majority of respondents were first year students just completing their first semester.

Table 2. Survey Responses Included

The researchers added a permission question at the end of the questionnaire asking if the contents of the app could be studied by the researchers and 63 students gave their permission by supplying their student ID number. The analysis of learners’ work will be the focus of a separate paper.

The questionnaire contained both closed and open response items which had been shared with colleagues prior to its administration and feedback incorporated. The questionnaire was then piloted with a similar cohort of students. The first part of the questionnaire was a general course evaluation which has not been included in this paper. Incidentally, the feedback from students on the course and instructors, as usual, was extremely positive. The two questions relevant to the present research were both open-response questions related to the influence (if any) the app had on their learning and what functions the students would like to see on an improved tool for learning.

The open-ended questions were coded qualitatively according to emergent themes by two researchers (the authors) making use of the qualitative software programme HyperResearch. The researchers completed the analysis together and created and negotiated the categories together, merging and separating themes during the coding process.

Results

Advisors’ perceptions

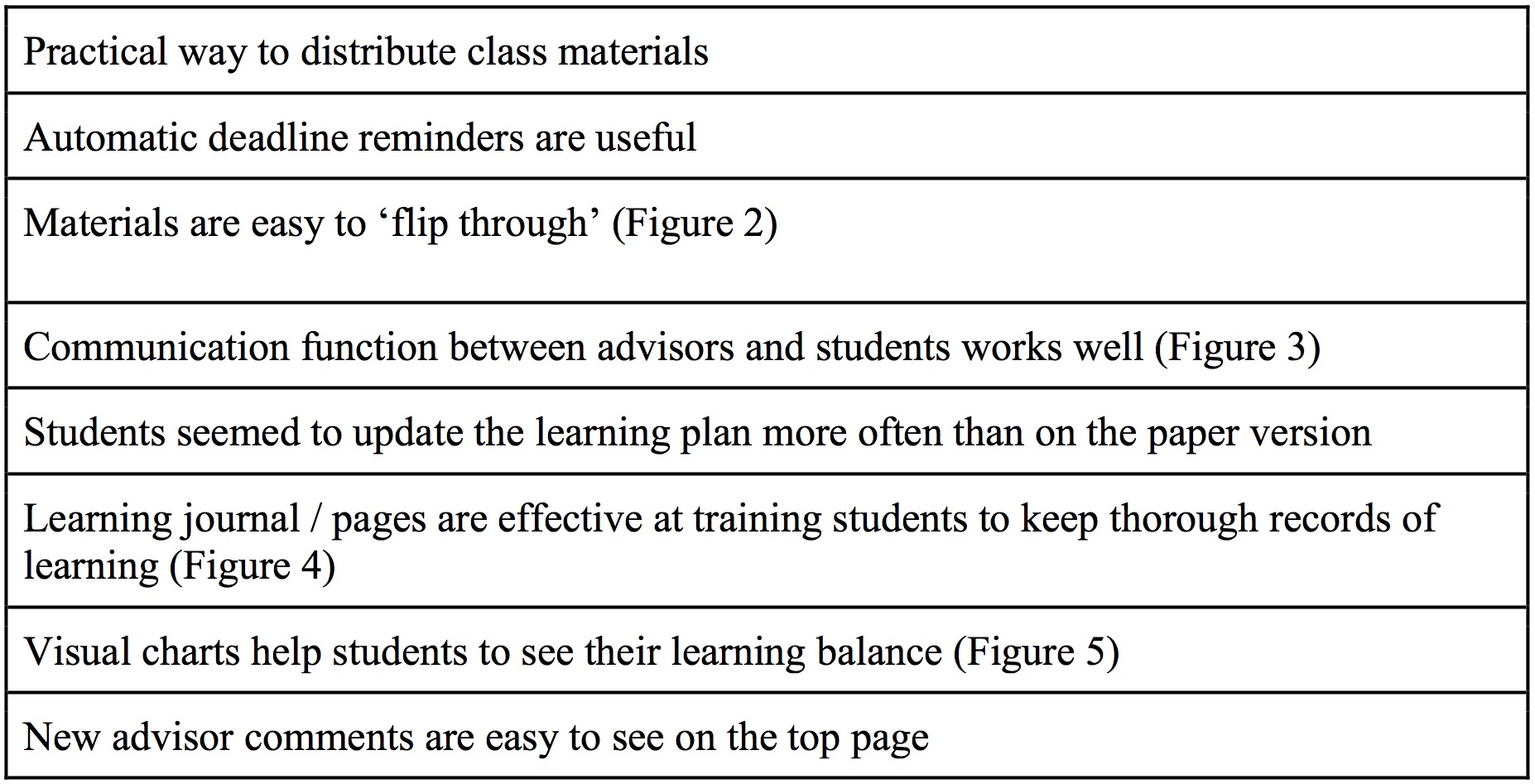

Advisors identified several benefits and challenges through the focus group discussions and follow-up comments which will be summarised here. Table 3 summarises advisors’ positive comments about the app. These are important to document so that future iterations of the app can take these into account.

Table 3. Advisors’ Positive Comments About the App

The main positive features will be described in the following paragraphs.

Practical benefits

Advisors mentioned that the app represented a practical way to provide classroom materials to students and was more efficient than photocopying materials as is the normal practice.

Useful functions.

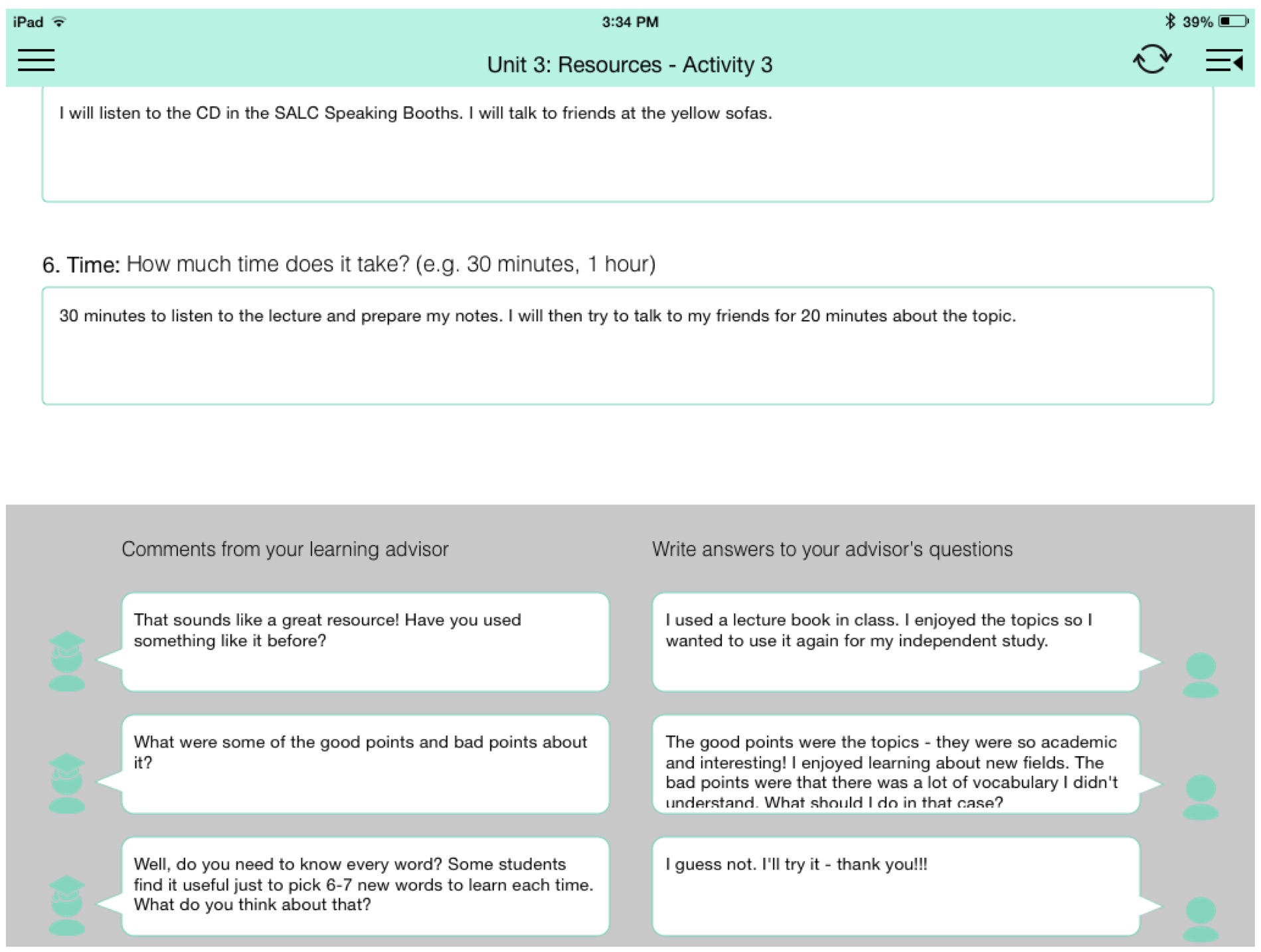

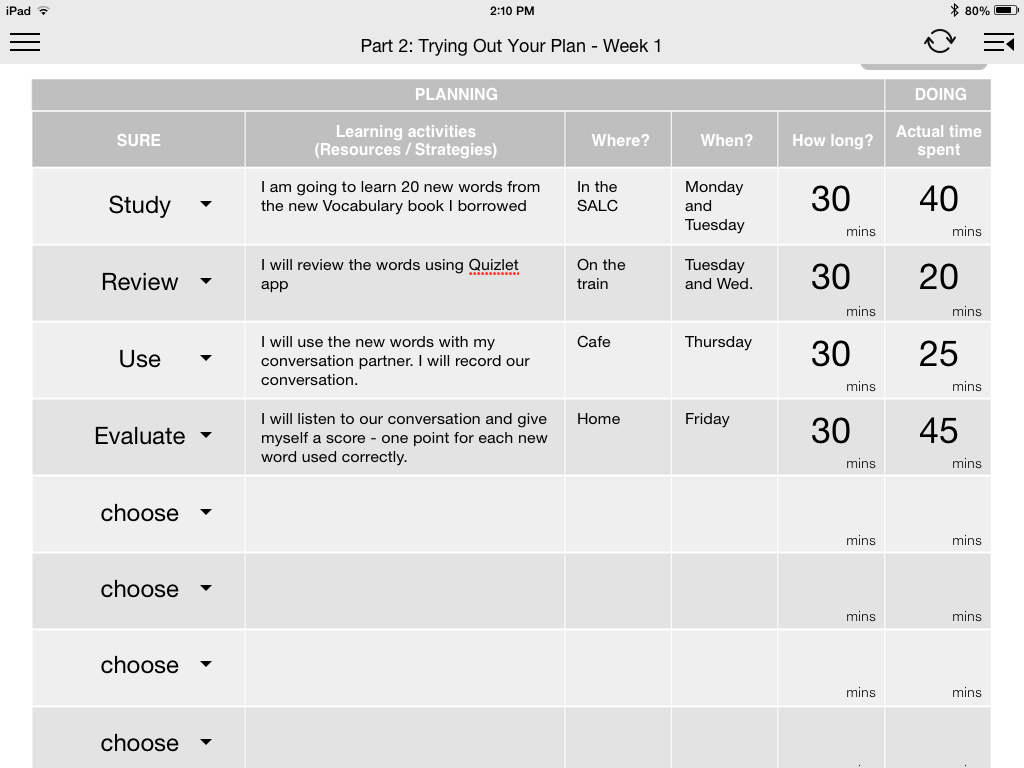

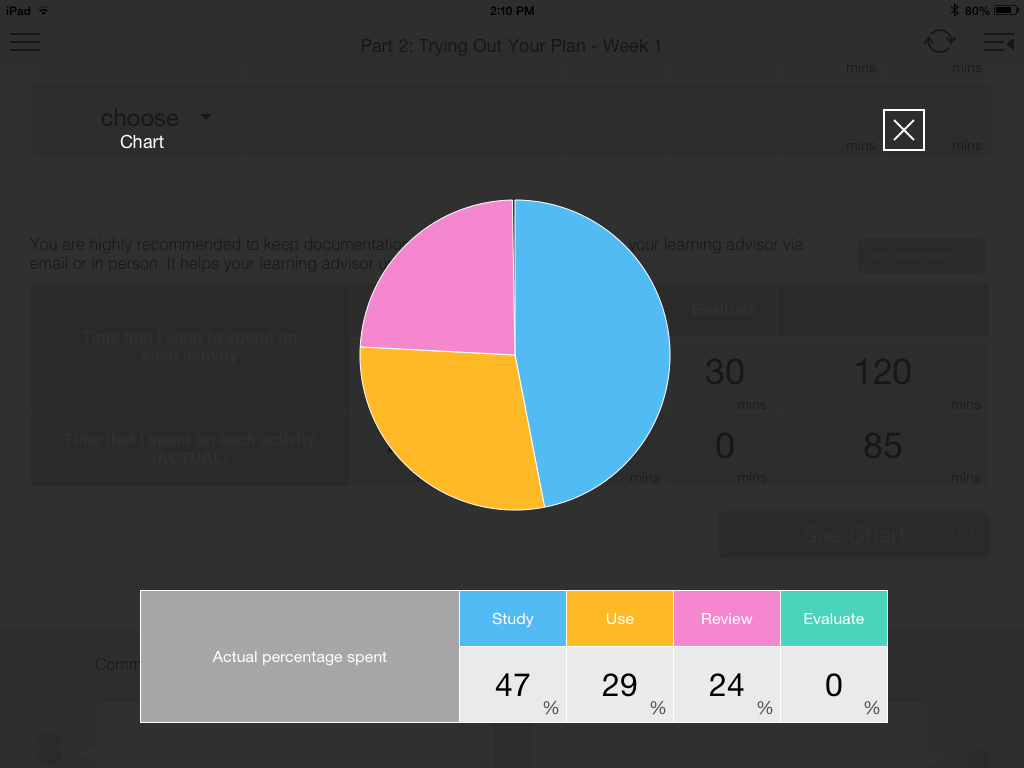

Deadline reminders were deemed particularly useful as were the text boxes (Figure 3) where advisors could interact with students in an extended dialogue. In addition, students seemed to be able to flip through units easily to refer to content (Figure 2). The advisor comments appear on the front page which make them easy for students to notice. Advisors believed that students updated their learning plan more in the app version than previously which was seen as positive. Advisors were also positive about the learning journal planning feature (Figure 4) which is not possible on the paper version. The visual chart indicating the balance of learning (Figure 5) was also perceived to be a positive feature of the app.

Figure 2. Navigation Page

Figure 3. Dialogue Boxes

Figure 4. Journal Planning Feature

Figure 5. Visual Chart Showing Balance of Learning Activities

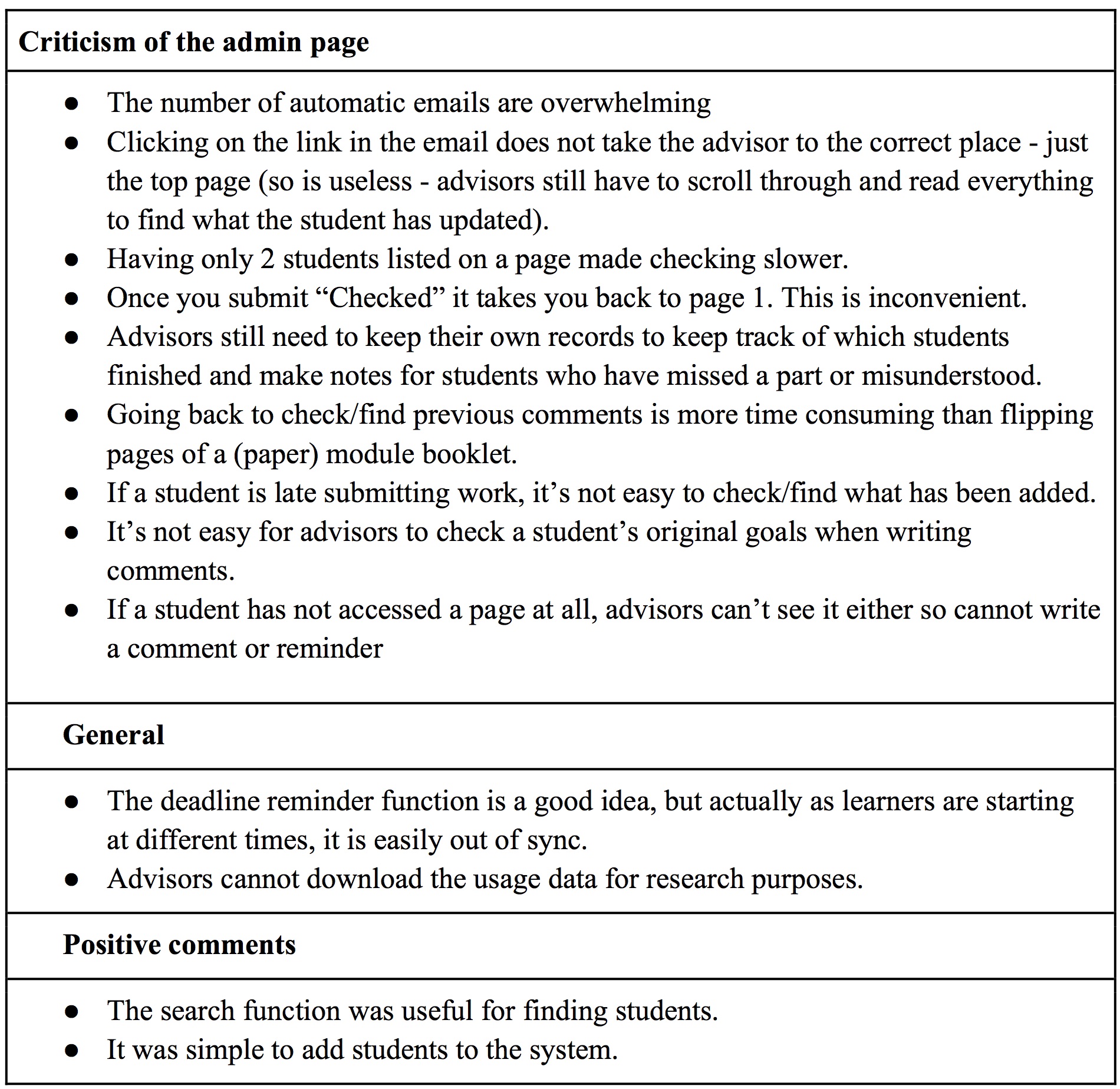

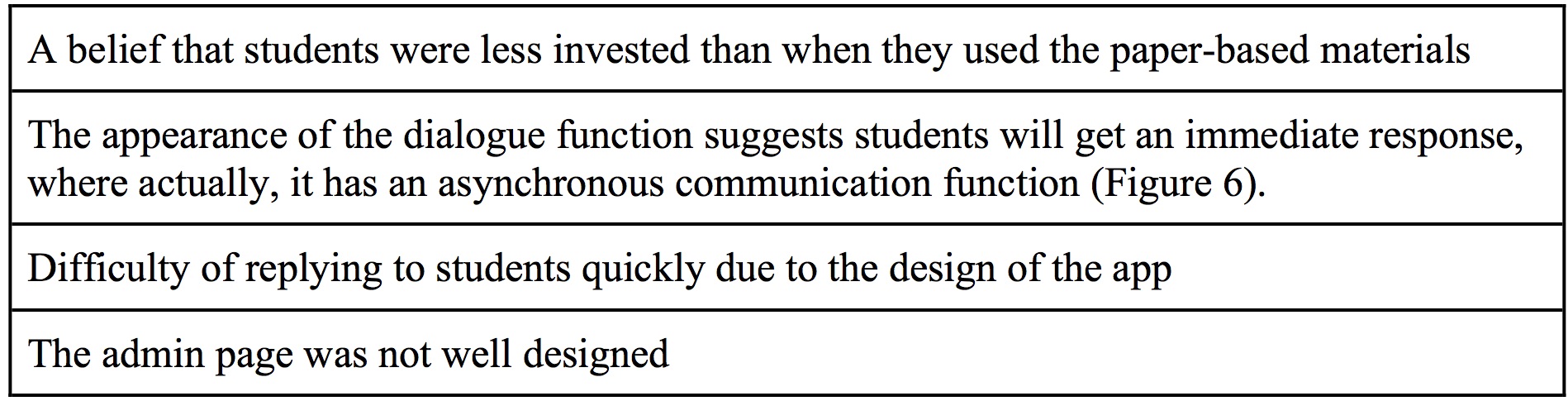

The negative features of the app are summarised in Table 4 and described in the paragraphs below.

Table 4. Advisors’ Negative Comments About the App.

Assumptions about investment by learners

Although it was difficult to support with evidence and this is admittedly impressionistic, advisors had a general sense that students were not as invested in the app version as previous students had been in the paper version. Advisors felt that the students were not as thorough or thoughtful when writing reflections on the app version as in previous years where students used the paper version. When the researchers viewed samples of student writing on the app, it was clear that students wrote less than the students normally did when using the paper-based materials, but a more thorough analysis needs to be done before any conclusions can be reached. In addition, the nature of an app and the amount of space available for written text are certainly factors that need to be taken into account. Interestingly, from the limited preliminary analysis of the written exchanges, the researchers saw little evidence of advisor ‘voice’ and few examples of creative ways to personalising the interactions. Conversely, with paper versions of the app, the majority of advisors use stickers, emoticons or drawings as a means of personalising their comments for the individual learners, yet the app did not allow for this kind interaction.

Appearance of the dialogue function

Although the comments function (Figure 6) was believed to be positive, the design made it look like an instant message or chat dialogue. However, the communication is in fact asynchronous and advisors usually only replied once a week. There were two reasons why advisors did not use the comment function synchronously (which may actually have benefits, but this is not investigated in the present paper). Firstly, the comment function could only be used via the management system on a computer which made commenting an overly lengthy process; whereas other tools such as Facebook or Google Messenger allow people to communicate and reply quickly via mobile devices or PCs, the app made replying to comments a cumbersome process requiring several steps. Secondly, the courses were originally designed for feedback be given to students just once per week in order to promote deeper reflection on learning while also maintaining a realistic workload for advisors. The app appearance did actually facilitate turn taking and potentially promote deeper learning through multiple short comments rather than one extended one, but it was quite demanding for advisors to locate and manage multiple learner conversation threads within the time allotted for responding to students.

Figure 6. Dialogue Function

Feedback on the admin page

Many advisor complaints related to problems with the admin page and they felt that the admin page was not well designed. Table 5 summarises the specific points raised.

Table 5. Advisors’ Comments About the Admin Page of the App

Features Advisors Would Like in the Future

Ability to update content themselves

Advisors often make changes, usually small, to the content of the paper version at the end of each semester taking into account newly available tools and resources, user feedback, and how activities are completed by learners. They would like to be able to update the content of the app in the same way themselves.

Portfolio function

Students are required to keep documentation of their work and it would be useful if the app could incorporate a function to add links, texts, photos, videos and screenshots.

Data download feature

It would be useful to be able to download the text for data analysis purposes. Also, advisors would ideally like access to the usage data such as

- How long students spend on each activity

- In which order students complete the activities

- Which activities are skipped

- The average number of words students type per section

- Keywords typed by students for each activity

- Date and time of access

- Whether students refer back to their learning plan regularly

- Whether students update content, how, and how often

- Whether students access links

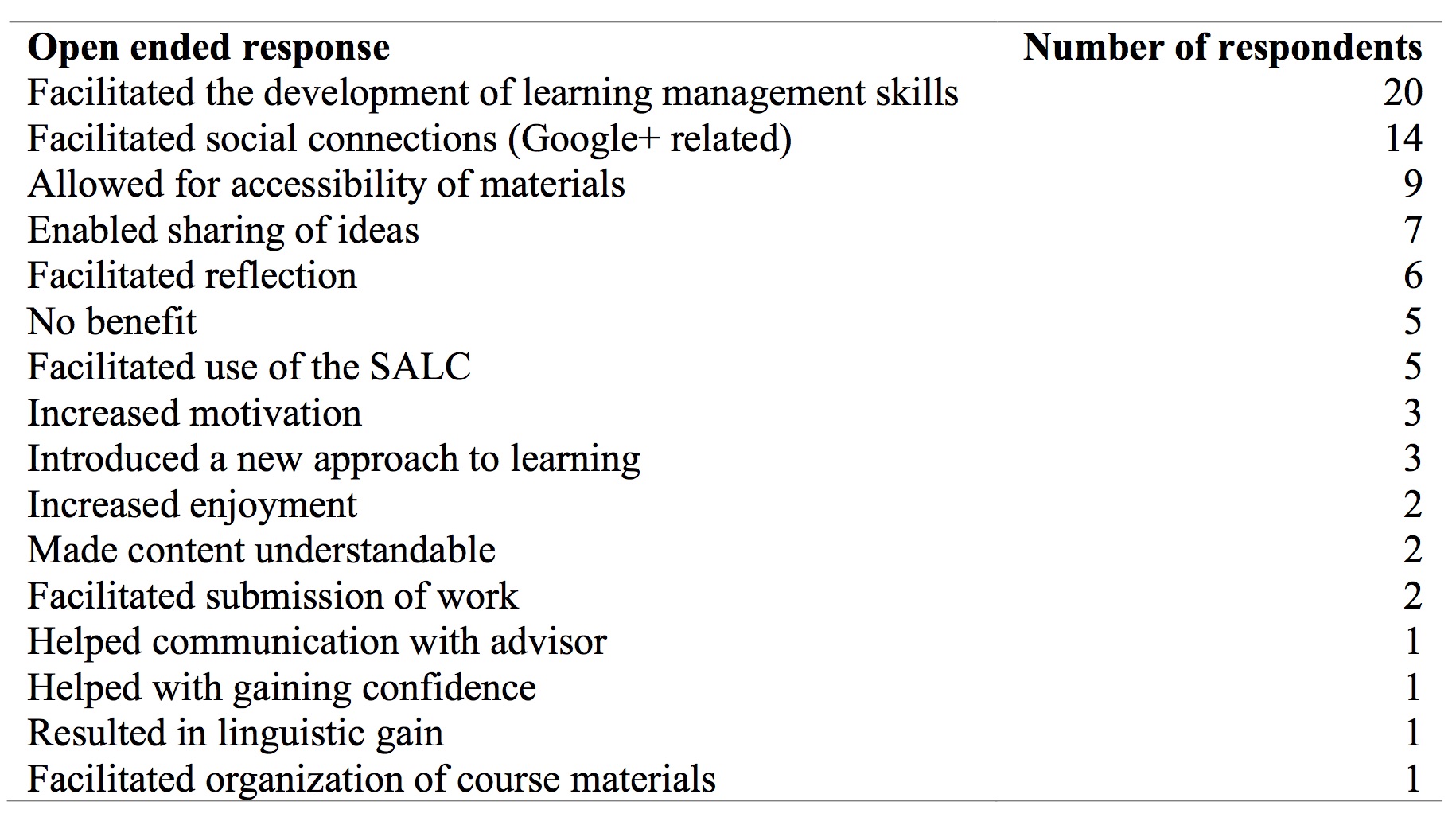

Students’ Perspectives

Impact on learning

Although establishing whether the app had any impact on learning is difficult to measure, one way to at least begin to investigate its potential is to ask the users. As no prior data had been collected related to impact on learning, the researchers decided to insert an open-ended question on the usual end-of-course survey asking “What impact (if any) did the course assignments using the apps such as SALC module app and Google+ to have on your learning?” (SALCアプリやGoogle+を使用した課題はあなたの英語学習にどのような影響を与えましたか。出来るだけ詳しく教えてください。). The open-ended responses were coded and the results are presented in Table 6. Some of the main themes that emerged are presented below the table with some extracts from the open-ended questions.

Table 6. Ways in Which Students Perceived the App to Benefit Their Learning

Learning management skills

20 respondents claimed that the app helped them develop learning management skills, for example habit formation like the following extracts indicate:

週に1回必ず自分の学習進度をチェックする習慣がついた。The app created a habit to check my learning progress every week no matter what.

計画を立てて、それを実行するという習慣がついた。It helped me develop a habit to create a plan and implement it.

The app also helped some students organise their work:

SALCアプリなどを使ったことでとても資料などの管理が紙に比べてしやすかった The SALC app helped me organize the course materials.

Two respondents mentioned how the app allowed them to visualise aspects of their learning easily:

SALCアプリは、自分が立てた計画や細かい時間配分などパッと見てわかりやすいからとても良かった。 The app was great because it visualises my plan and actual time to be spent at a glance.

Social function

14 respondents mentioned some features that helped their learning, but these were actually features of Google+ which some of the instructors had used in order to overcome the social networking limitations of the app. However, it is useful to include these points in this research as they might be included in a future version of an app or other tool.

Accessibility

The third largest category was ‘Accessibility’. Some students mentioned how easy and convenient the tool was, but others maintained that a paper version would have been easier.

わかりやすく、簡単に課題を提出することができた。The app was easy to understand and helped me submit my coursework easily.

Wi-Fiが家にないので、学校で終わらせないといけなかった。大変だった。Using the app was hard because I don’t have wifi at home. Therefore, I had to finish all the work on campus.

What Features Would Students Like to See on a Future Tool for Learning?

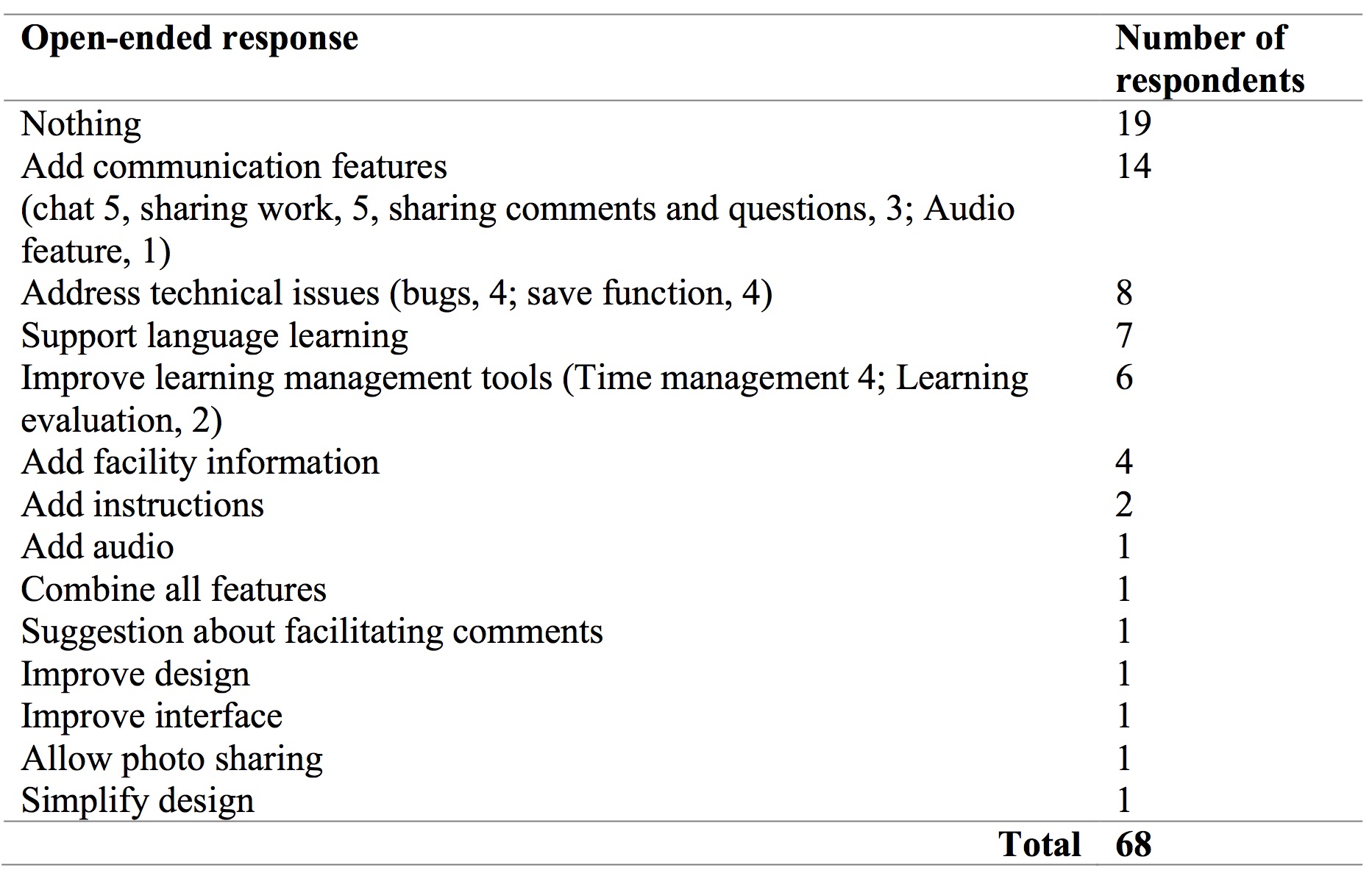

The students were asked to comment on what features they would like to see in a future app (SALCアプリにどのような機能があったら良いと思いますか。). There were 68 coded items related to this question (not all students responded to the question and some students provided more than one response). 19 respondents did not have any suggestions or indicated that they were satisfied with the current app. The items are summarised in Table 7.

Table 7. Other Features Students Recommend Including in a Future App

Communication feature

13 responses related to adding a communication feature. Five students requested a chat or instant message function, and eight students suggested that the ability to share work and ideas with others would be useful, and, e.g.

それぞれの英語の能力を高められる本のおすすめを上げる。[Sharing a recommended book among students]

Technical features

Eight responses related to technical features. Four of these comments identified bugs in the current app and four requested a ‘save’ function.

Language learning

Seven responses were directly related to language learning features. For example, suggestions to provide learning tips, links to tests, language games, or (as in the following example) “fun English”:

えいごで面白いことを教えてくれる機能 [A function that shares something fun in English]

Discussion

Advisors’ were rather critical of the app, but as one of the main stakeholders in the project who have considerable experience and knowledge about ways to effectively promote learner autonomy, their feedback is absolutely crucial. Although the learners mostly had no experience with this kind of learning or with using apps for learning, their insights can still guide us when designing future iterations. Generally speaking, although this version of the app had some significant limitations, it did provide some useful benefits for learners related to good learning management. In addition, this research was a step towards helping us to understand how learning could be further enhanced. In terms of whether the app contributed to the features of the FFA Model (Hughes et al., 2011), namely replacement, amplification, and transformation, more research is needed, but comments will be made in the relevant sections below.

Communication functions

One of the main limitations of the app was the limited communication functions. The majority of advisors had had previous experience in writing comments on the paper-based version of the materials. Advisors’ insights indicated how highly they valued flexibility in terms of personalising comments for learners. Simultaneously, interaction between an advisor and his/her advisee is considered to be a foundation of written advising. Thus, ensuring effective communication between advisors and learners is fundamental to the role of facilitating learning, this means the addition of an instant messaging function. In addition, the inclusion of commenting tools such as stickers and highlighters might overcome the lack of personalised dialogues on the app. Similarly, students commented on the need to improve the communication features not only with their advisors, but also with other learners. Communication could be improved with the addition of multimodal features such as pictures, video and audio in addition to text. The inclusion of social networking functions is also recommended in a future version of the app. Relating this to the FFA model (Hughes et al., 2011), the app did not sufficiently replace, amplify or transform the communication opportunities afforded by the paper version of the materials.

Convenience

Convenience is another significant concept that influenced users’ perceptions of the app. On the one hand, material distribution was efficient and students could keep all of their self-directed learning work in one place. As seen in the previous section, overall student comments were positive. However, the need for wifi to use the app inhibited use and caused problems when students wanted to write drafts offline as they were unable to save their work. In addition, the app was device specific meaning that users did not have a choice of how and where to work. Ideally, apps promoting self-directed learning should allow the users the choice of which device to use and the option to be able to engage in self-directed learning outside the classroom. Moreover, the admin page was particularly inconvenient for advisors and there was substantial criticism which resulted in advisors choosing not to use the app after one semester despite some acknowledged learning benefits for students. It is evident that the lack of convenience significantly influenced advisors’ willingness to invest in using the app. Relating convenience to the FFA model (Hughes et al., 2011), the app did offer a suitable (but limited) method of replacement, however, there was no evidence that the app could amplify or transform learning opportunities due to some of its inconvenient features. Further investigations are needed in order to be able to comment on amplification and transformation adequately.

Impact on learning

Impact on learning was investigated through students’ responses to the question “What impact (if any) did the app to have on your learning?” on the questionnaire and from some of the comments discussed by advisors in the focus groups. Results indicate that the app enabled students to manage their learning effectively, implement a learning plan effectively and see their learning holistically and visually. A documentation feature was missing from the app so students could not keep a record of their self-directed work within the app itself. This meant that all the self-directed learning activities were not available in one place when students were writing their final reflections. This was a missed opportunity for the promotion of deeper reflection by allowing users to look back at documentation and see their progress. A feature allowing learners to document, share their work with other learners and invite comments on their documentation, would be one way to enhance opportunities for reflection and deeper learning. Relating this impact to the FFA model (Hughes et al., 2011), the app offered opportunities for amplification through the design of the learning management system, however, it remains unclear whether the app could contribute to transformational learning due to its design limitations.

Limitations

This study only looks at user perceptions and thus has limited results. One of the main reasons for exploring technology use was to investigate how learning could be enhanced and how it could contribute to transformative learning and this project could only look at this in a very shallow way through user perceptions. Interviews or focus group discussions should have been conducted to ascertain more details about the learners’ experiences and views on using the app. In addition, the researchers originally planned to draw upon evidence contributed by the learners actually using the app. This kind of analysis was previously conducted successfully with the written version of the materials (Curry, Mynard, Noguchi, & Watkins, 2017; Mynard, Curry, Noguchi & Watkins, 2016), showing ways in which ELLC 1 supported the development of SDL skills. However, less learner-generated text was produced using the app, so this kind analysis was difficult to do. In addition, the written learner contributions would only be one source of evidence and ideally the researchers would need access to classroom interactions, the portfolio of self-directed work, recordings of individual advising sessions and any other activities that might have supported learning alongside the app or indicated where the app played a role in learning.

Conclusions and Future Directions

This paper has reported on the evaluation of the app developed for enhancing self-directed language learning skills drawing on the users’ perceptions. As discussed throughout this paper, implementing the app use enabled the researchers to clarify which stage they were in terms of developing transformational learning. Overall, replacing the written dialogues as well as learning materials online appeared to be successfully achieved. However, advisors, who play crucial roles in facilitating transformational learning, faced administrative challenges in working with individual students via the app. This lead to a great degree of frustration and a negative perception of the app despite the acknowledged learning benefits.

Although the app was discontinued in this case, the advisor team is continuing to research alternatives. The researchers found that advisors appreciated opportunities to customise materials in order to support learners either by providing other online resources or paper-based activities. This also increases the buy-in that advisors have in any future the app or technology-based tool. The app being researched in this paper was very structured and allowed for very little advisor or learner ownership, customisation or creativity which was a severe limitation. A more integrated tool with more flexibility would be preferable in the future, but one that still facilitates learning self-management. From the learner’s perspective, increased opportunities for sharing an interaction, plus flexibility of use would be of prime consideration for any new app or tool being considered in the future.

The next steps have been taken to consider future approaches that may draw upon the potential affordances for self-directed learning. These include working with a team of technology and design experts from the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH) Sweden who visited the SALC and have conducted a needs assessment. An important part of this assessment was to involve all of the stakeholders, particularly the students, in the design and creation process right from the beginning. For an overview of the collaborative process between KUIS and KTH so far, see Viberg, Laaksolahti, Mavroudi, and Mynard (2018). Ongoing papers will continue to be published during the coming years allowing the team to research and document the process carefully in order to create optimal learning conditions for students.

Notes on the contributors

Jo Mynard is a Professor in the English department, Director of the Self-Access Learning Center, and Director of the Research Institute for Learner Autonomy Education at Kanda University of International Studies in Japan. She has an M.Phil. in Applied Linguistics from Trinity College, University of Dublin (Ireland) and an Ed.D. in TEFL from the University of Exeter (UK).

Kie Yamamoto is a learning advisor at Kanda University of International Studies. She holds an M.S.Ed from Temple University Japan, and is currently pursuing an Ed.D at the University of Bath in the UK. Her research interests are language learner identity, social learning theory, student engagement, and narrative analysis.

References

Benson, P. (2011a). Language learning and teaching beyond the classroom: An introduction to the field. In P. Benson & H. Reinders (Eds.), Beyond the language classroom (pp. 7–16). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Benson, P. (2011b). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning(2nd ed.). Harlow, UK: Pearson.

Curry, N., Mynard, J., Noguchi, J., & Watkins, S. (2017). Evaluating a self-directed language learning course in a Japanese university. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 14(1), 37-57. Retrieved from http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/dfdeaf_385a2e4d19254f968487b6058464e00c.pdf

Dickinson, L. (1987). Self-instruction in language learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dickinson, L. (1995). Autonomy and motivation: A literature review. System, 23(2), 165-174. doi:10.1016/0346-251X(95)00005-5

Hiemstra, R. (2013). Self-directed learning: Why do most instructors still do it wrong? International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 10(1), 23-34. Retrieved from http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/dfdeaf_e996f035b2094c38a1492317121bacf1.pdf

Hughes, J. E., Guion, J., Bruce, K., Horton, L., & Prescott, A. (2011). A framework for action: Intervening to increase adoption of transformative web 2.0 learning resources. Educational Technology, 51(2), 53-61.

Lammons, E., Momata, Y., Mynard, J., Noguchi, J., & Watkins, S. (2016). Developing and piloting an app for managing self-directed language learning: An action research approach. In F. Helm, L. Bradley, M. Guarda, & S. Thouësny (Eds.), Critical CALL – Proceedings of the 2015 EUROCALL Conference, Padova, Italy (pp. 342-347). Research-Publishing.net. doi:10.14705/rpnet.2015.000356

Krueger, R. A. (1994). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. London, UK: Sage Publications Ltd.

Lammons, E., Mynard, J., & Yamamoto, K. (2016, June). Student voices: Evaluating an app for promoting self-directed language learning. Paper presented at JALT CALL annual conference, Tokyo, Japan. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/25879656/Student_Voices_Evaluating_an_App_for_Promoting_Self-directed_Language_Learning

Morrison, B. R. (2013). Learning behaviors: Subtle barriers in L2 learning. In J. Schwieter (Ed.), Studies and global perspectives of second language teaching and learning (pp. 69-89). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Murray, G. (2004). Two stories of self-directed language learning. In H. Reinders, H. Anderson, M. Hobbs, & J. Jones-Parry (Eds.), Supporting independent learning in the 21st century. Proceedings of the inaugural conference of the Independent Learning Association, Melbourne, September 13-14 2003 (pp. 112-120). Auckland, New Zealand: Independent Learning Association Oceania. Retrieved from http://www.independentlearning.org/ila03/ila03_papers.htm

Mynard, J., & Stevenson, R. (2017). Promoting learner autonomy and self-directed learning: The evolution of a SALC curriculum. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 169-182. Retrieved from https://sisaljournal.org/archives/jun2017/mynard_stevenson/

Mynard, J., Curry, N., Noguchi, J., & Watkins, S. (2016). Studying the impact of the SALC curriculum on learning. Studies in Linguistics and Language Teaching, 28, 45-58.

Reinders, H., & White, C. (2016). 20 years of autonomy and technology: How far have we come and where to next? Language Learning & Technology, 20(2), 143–154. http://dx.doi.org/10125/44466

Reinders, H. (2007). Big brother is helping you: Supporting self-access language learning with a student monitoring system. System, 35(1), 93–111.

Thornton, K. (2013). A framework for curriculum reform: Re-designing a curriculum for self-directed learning. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 4(2), 142-153. Retrieved from http://sisaljournal.org/archives/june13/thornton/

Viberg, O., Laaksolahti, J., Mavroudi, A., & Mynard. J. (2018). Assessing the potential role of technology in promoting self-directed language Learning: A collaborative project between Japan and Sweden. Relay Journal, 1(2).

I enjoyed reading about your app and the brave efforts of motivating students to take more responsibility for self-directing their learning using technology. It was very interesting to read about teachers’ and learners’ experiences, all of which reinforce the fact that innovation is never simple and never dependent on (for example) just a new technology or just a new idea; a lot of things need to come together to make an innovation stick. Even something as mundane as a difficult login procedure can – clearly – limit the success of a new technology; a good reminder to always start from the user and their experiences.

In terms of recommendations, as the app is the focus of your article, I would suggest you (very briefly) describe it in the abstract. What aspects of SDL did it try to support? How?

Another suggestion would be to provide more of a rationale for the development of the app. What did you anticipate it would help you achieve that paper-based materials did/do not? On what basis did you expect this

Related to this, I suspect many of us would be keen to understand more about the context in which the iPads were provided and the app was developed. Who initiated the idea and who approved it? Who funded it? Who was involved? In other words, can you tell us a little more about the ‘innovation process’? (Your description of the university and the SALC is quite long so perhaps that section could be shortened a bit?)

Thank you again for sharing your fascinating work!