Dominique Vola Ambinintsoa, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan

Ambinintsoa, D. V. (2020). Using an advising tool to help students go beyond “just learning”, Relay Journal, 3(2), 221-228. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/030207

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

The role of a learning advisor (LA) in a self-access centre (SAC) is to help learners develop their learner autonomy (Carson & Mynard, 2012), defined as “the capacity to control over [their] learning” (Benson, 2011, p. 2). To develop such a capacity, learners need to be aware of their learning. With the aim to help learners, a learning advisor uses different advising strategies and advising tools. However, for a novice learning advisor, it is not always obvious to introduce an advising tool to a student. In this article, I describe how I, a novice learning advisor, used an advising tool, called the Wheel of Language Learning (WLL) with a student in her first advising session with me, and how it impacted her perspectives on her learning. In the end, I give some implications for future advising sessions.

Keywords: goal setting, ownership, advising tool, Wheel of Language Learning

I have been working as a learning advisor (LA) for three months at a university in Japan. My learning advising role consists in helping learners raise their awareness on their learning processes, identify their needs, and set their learning goals accordingly (Carson & Mynard, 2012). For that purpose, I help learners reflect on aspects of their learning by means of dialogue involving advising strategies and advising tools (Kato & Mynard, 2016) during advising sessions. Having used advising tools on myself and with colleagues as part of my advising training, I came to know how those tools trigger deep reflections. Among the tools I had used, the Wheel of Language Learning (WLL) was particularly powerful in terms of raising self-awareness. That is why I decided to use an adapted version of it with a student. However, I was aware that it may not have the same power as it had on me and my colleagues, as we are more used to self-reflection due to our advising training and our life experience.

The student described here, Aina (a pseudonym), is a senior student majoring in International Communication. She has been learning English at the university for more than three years. During an internship abroad, she decided to learn Indonesian, and continued the language at the university. By the time of the advising session, she had been learning Indonesian for a year. When asked about her level of Indonesian, she expressed her lack of confidence in speaking, which was due to her lack of ability to memorize vocabulary, according to her. She chose to talk about her Indonesian during the session, as she thought she would need more ‘advice’ on her Indonesian than on her English.

It is worth noting that it was the first time we had met, which explained why I did not feel really confident using the WLL. As recommended in Kato and Mynard (2016) and also by some of my LA colleagues, the first session with a student is about getting to know him or her and building trust by fully listening to what he or she has to say. Therefore, most of the time, my LA colleagues would not use a tool in the first session.

Purpose of the Session

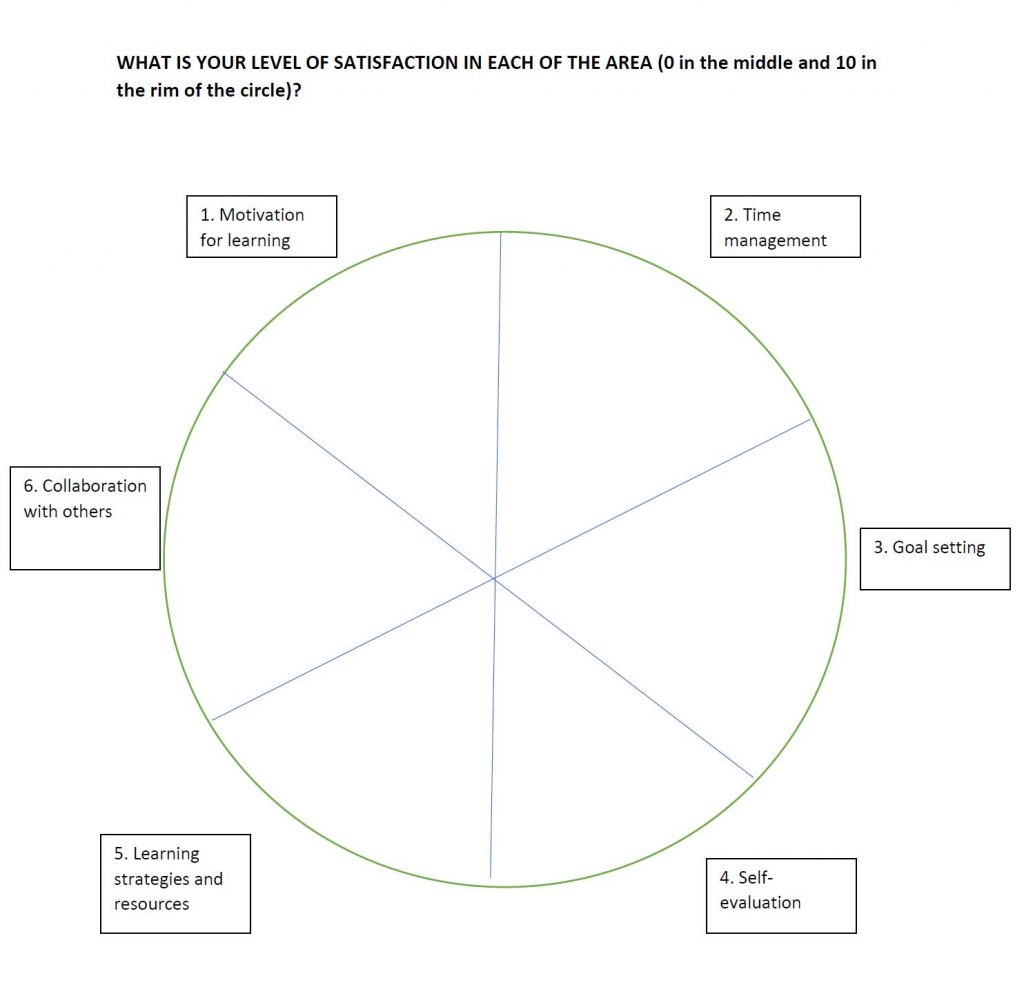

The session was held online via Zoom. The main purpose of the session was for me to try an advising tool, and I decided to use a WLL due to the reason I stated above. I wanted to know to what extent a WLL can help the student reflect on her own learning. I adapted the WLL in Kato and Mynard (2016, p. 42), which has six areas: time management, goal setting, learning materials, enjoyment in learning, motivation, and learning strategies. I kept time management, goal setting, and motivation. I merged learning strategies and learning materials. Then, I added self-evaluation because like goal setting, self-evaluation is an important metacognitive skill (Nguyen & Gu, 2013; Wenden, 1991), which enables increased student reflection and control (Smith, 2003), and which should be closely related to goals (Locke & Latham, 2002; Zimmerman, 2002). I also added collaboration with others, considering the importance of peer collaboration through interaction in language learning (Benson, 2011; Oxford, 2003; Palfreyman, 2018) and the necessity of interdependence for the development of learner autonomy (Dam et al., 1990; Murray, 2014; Tassinari, 2012). Figure 1 shows the WLL as presented to Aina.

Figure 1. Wheel of Language Learning

Details of the Session

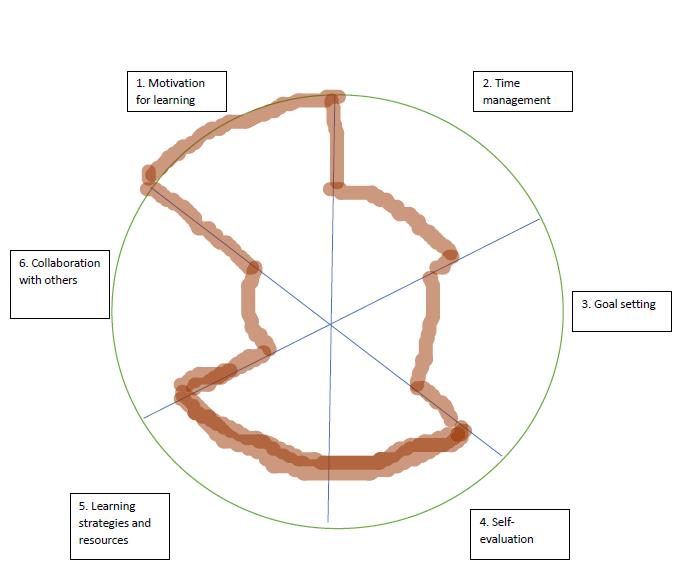

Unfortunately, due to some technical issues, Aina could not annotate the wheel on her screen. After trying for a while, I decided she could just say what score from 0 to 10 she would give to each area of the WLL, then to explain the reason of the score. Figure 2 (see next page) shows what the WLL would have looked like with Aina’s answers if annotation had been possible.

After introducing herself, including her experience abroad, Aina started talking about her motivation, to which she gave a score of 10 without hesitation: “Motivation for learning is, yeah, definitely, 10 because I want to understand more about Indonesian language and also the culture.” That statement was highlighted by the enthusiasm in her voice and the smile on her face. She went on talking about the other areas, which were not as satisfying to her as motivation. For time management, for instance, she started by saying that she cannot afford the time to learn Indonesian. After I restated what she had said, she said that apart from her classes, she had not done anything else to improve her Indonesian, and she, therefore would like to do more self-directed learning. Likewise, she was not satisfied with her goal setting, as she did not have small goals: “Like big goals, I can speak fluent, just like that, like I don’t have any […] how to say it, the order to reach that goal, like small goal.” When asked if she was happy with that, she replied that she was not. She explained that she had not set small goals because she was aware that there were no opportunities for her to use Indonesian in the Japanese society and she just wanted to “learn new things”. In other words, as she had not seen the immediate necessity to use Indonesian in real life, she had not thought of having any learning plan with specific goals. However, talking about goal setting in the session reminded her the importance of having specific goals: “If I have the goal, I can approach that goal […], like, I can learn for the goals, and maybe I can concentrate more on what I need, like that. I can maybe more clear my reason why I study this.” Similarly, when talking about learning strategies and resources, she said she had been using only resources from her class, but now, she would like to find more resources related to movies or other entertainment. Regarding her self-evaluation, though she was not totally satisfied, she felt that she had been able to evaluate her own learning by noticing improvement in her understanding when watching programs involving Indonesian celebrities. Lastly, she was not happy with her collaboration with others, as she did not have any friends learning Indonesian, and she did not feel close enough to her classmates to reach out for them outside class. On the other hand, she felt that she was still in a phase where she needed to learn more independently (building vocabulary and practicing listening) than in collaboration with others.

Figure 2. Aina’s WLL

Reflection on the Session

Aina used the adverb “definitely” when talking about her considerably high motivation, showing her absolute certainty. Yet, she admitted that she had not set any specific goals. She also expressed her wish for more time for self-directed learning, including looking for more resources, as she had been using only textbooks used in her class. At the end of the session, I asked her if she had noticed any benefits from the session. She answered,

I can find my weakness and what I really want to do. So, maybe for example, I want to get the small goals. I want to get more strategies and resources, but for now, I’m just learning without any goals or something. I am just learning. Sometimes, it’s boring, right?

Aina’s case demonstrates that even with a very high motivation, students may not always be aware of the indispensability of setting goals and making all necessary effort to learn in a self-directed way, such as allocating time, finding resources and more opportunities to learn until they are “triggered” to do so. A way to trigger this is to use the WLL. The latter is said to be a powerful tool because it allows students to “actually ‘see’ where they are at now” (Kato & Mynard, 2016, p. 141). It shows students a visualization of the connection of different learning skills and of the necessity to balance their focus on the skills. Though Aina could not physically see the shape of her wheel, she was able to reflect on each of the skills or areas, and to recall the areas that needed improving at the end of the session. The use of WLL in the session enabled her to realize that she needed to do some learning beyond the classroom. In other words, she became aware that, instead of “just learning”, having her learning more structured by means of setting small goals and using more resources would help her improve her language skills and maintain her high motivation. The session guided her into taking more ownership of her learning.

Conclusion and Implications on Future Sessions

I will suggest the use of the WLL with my advisees for the following reasons. Firstly, the session with Aina demonstrated that the WLL can be used in a first advising session. Some students come to the first advising session with very general topics such as “how to learn English” or “how to improve speaking”, without being able to define what they need to improve specifically. Using WLL can help those students identify their weaknesses or specific areas they struggle with. On the other hand, it enables them to think of areas they may have never considered, and yet are fundamental for their learning. Thinking of such areas raises their awareness of their responsibility towards their learning. For students who have been used to being given instructions on what to do, for instance, they may not know that they should have goals, find strategies and resources, and know how to evaluate their learning. They may “just learn”, as Aina puts it. Thus, using a WLL is a way to lead students to take charge of their learning, and thus, to develop their learner autonomy. Secondly, a WLL can be a useful tool for students having continuous advising sessions. It can serve as a starter and as a guide of the session when the student does not know where to begin. Also, it can be helpful for students who find it difficult to perceive improvement in certain areas. A WLL allows comparisons if used more than once, thereby facilitating self-evaluation.

I do not mean, however, that learning advisors should jump into using a WLL every time they think their students do not have a clear idea of what they need to improve. Though the use of WLL is feasible in a first session, it is also important to build rapport, that is, to take the time to know the students and to help them elicit the issue they think they have by using advising strategies such as repeating and restating what they say and asking them questions. Then, if it is still difficult for them to identify their needs or weaknesses, the learning advisor can introduce a WLL in the session or suggest a second session using it. In any case, it would be necessary to explain to students why using a WLL (or any other tools) can be beneficial to them, and to ask their permission before using it.

Although the session with Aina went smoothly, it would have been better if I had taken more time to ask more specific questions and highlighted some key points. For instance, when she expressed her high motivation, I should have encouraged her to reflect on the origin of that motivation and of her interest in the Indonesian culture. That would have enabled me to know her better, and on one hand would have allowed her to talk more about a language she finds important, and on another hand, perhaps, to be more aware of how much she values that language. To take another example, according to her, she had to start off independently at first before considering peer collaboration when learning a language, and that is why she thought peer collaboration was not necessary at her level. It would have been helpful to ask her the reason why she thought peer collaboration is needed only at a later stage. Perhaps, she misunderstood what was meant by peer collaboration, as she seemed to associate it with speaking practice only. Yet, peer collaboration includes sharing of resources, strategies, goals, positive and negative experiences, which can be greatly beneficial for her at any stage of her language learning. Furthermore, I should have helped her perceive the connection between her way of self-evaluating, her interests (in movies and entertainment), and her motivation. Putting the emphasis on those key points might have triggered deeper reflection and more awareness on her style of learning and the types of activities, materials, or strategies which are suitable to her.

Notes on the contributor

Dominique Vola Ambinintsoa is a learning advisor at Kanda University of International Studies, Japan. She holds a Master of Education in TESOL (State University of New York at Buffalo, US). Her PhD in applied linguistics focuses on fostering learner autonomy in an EFL Malagasy context (Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand). She has ten years of experience in ESL and EFL teaching. She has a particular interest in learner autonomy, self-access language learning, and advising.

References

Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching autonomy (Second ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833767

Carson, L., & Mynard, J. (2012). Introduction. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogs, tools and context. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833040

Dam, L., Eriksson, R., Gabrielsen, G., Little, D., Miliander, J. & Trebbi, T. (1990). Group II: Autonomy–Steps towards a definition. In T. Trebbi (Ed.), Report on the third Nordic workshop on developing autonomous learning in the FL classroom (pp. 96-103). Bergen University Institute for Pedagogic Practice.

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American psychologist, 57(9), 705-717. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.57.9.705

Murray, G. (2014). Exploring the social dimensions of autonomy in language learning. In G. Murray (Ed.), Social dimensions of autonomy in language learning (pp. 3-11). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137290243_1

Nguyen, L. T. C., & Gu, Y. (2013). Strategy-based instruction: A learner-focused approach to developing learner autonomy. Language Teaching Research, 17(1), 9-30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168812457528

Oxford, R. L. (2003). Language learning styles and strategies: An overview. Learning Styles & Strategies/Oxford, GALA, 2003, 1-25.

Palfreyman, D. M. (2018). Learner Autonomy and Groups. In Autonomy in Language Learning and Teaching (pp. 51-72). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-52998-5_4

Smith, R. (2003). Pedagogy for autonomy as (becoming-) appropriate methodology. In D. Palfreyman & R. Smith (Eds.), Learner autonomy across cultures – Language Education Perspectives (pp. 129-146). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230504684_8

Tassinari, M. G. (2012). Evaluating learner autonomy: A dynamic model with descriptors. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(1), 24-40. https://doi.org/10.37237/030103

Wenden, A. (1991). Learner strategies for learner autonomy. Prentice Hall.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into practice, 41(2), 64-70. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2

I like the way Ambinintsoa embraces the narrative style as she recounts her advising journey. Right from her opening paragraph I was drawn in by the flow of her words, her voice, following the current of her thoughts downstream. I was intrigued as Ambinintsoa introduces me to a new role – that of Learning Advisor (LA). Her introduction makes it clear that I’ll be learning about a practical tool that can be used by LA’s – the Wheel of Language Learning (WLL) – so I was hooked from the beginning and wanted to read more.

Once Ambinintsoa introduces and shares the WLL tool used in her advising session, she goes on to explain the six dimensions of the tool as originally developed. Ambinintsoa decided to adapt the tool to meet the needs of the advisee and provides a clear rationale for the adaptations supported by academic references. For instance, the author the category of ‘collaboration with others,’ which shows beliefs about the importance and benefits of peer interaction and social collaboration as well as the category of self-evaluation, highlighting the importance of metacognitive awareness. Both of these additions represent important improvements to the tool.

Next, the article itself is well structured. After Ambinintsoa explained what the adapted WLL tool was and how it worked during the session, the author outlined the progress the advisee had reported making during her first advising session. Finally, implications for future advising sessions are spelled out. This includes a review and self-critique of small things Ambinintsoa feels could have been addressed during the session. For someone like me who has little to no experience in the role of individual learning advisor, Ambinintsoa’s narrative of an initial advising session made for a pleasant introductory tour through this ‘new to me’ world. Her personable writing style made for a perfect journey, and I’m now thinking maybe I would greatly benefit from training in this area of individual learner advising.

In terms of language used, I found myself asking a few times whether the standard English I am used to is different in other parts of the world. I was second-guessing myself about the following:

“I wanted to know to what extent a WLL can help the student reflect on her own learning.” vs.

“I wanted to know the extent to which a WLL …”

However, talking about goal setting in the session reminded her [??] the importance of having specific goals

she did not feel close enough to her classmates to reach out [for] them outside class.

Thinking of such areas raises [their] awareness of [their] responsibility towards [their] learning.

they may not know that they should have goals, find strategies and resources, and know how to evaluate their learning. [parallelism?]

I was wondering whether the following sentence, which has three subordinators, might be more easily understood by the reader the first time around if it were broken down?

“Then, I added self-evaluation because like goal setting, self-evaluation is an important metacognitive skill (Nguyen & Gu, 2013; Wenden, 1991), which enables increased student reflection and control (Smith, 2003), and which should be closely related to goals (Locke & Latham, 2002; Zimmerman, 2002).”

.

Thank you for your feedback and for pointing out some positive points about the article. I am glad to know that the article has enabled you to know more about learner advising. I agree that the role of learning advisors is relatively new in many parts of the world, and most of the time, language learning advisors are often confused with tutors, whose role is more focused on directly solving learners’ linguistic problems by giving them tips, rather than on helping them reflect on the roots of their problems and take control of their learning gradually.