Christian Ludwig, Freie Universität Berlin in Berlin, Germany

Maria Giovanna Tassinari, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany

Sarah Mercer, University of Graz

Micòl Beseghi, University of Parma, Italy

Michelle Tamala

Katja Heim, University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany

Gamze A. Sayram, Macquarie University ELC, Sydney

Ludwig, C., Tassinari, M. G., Mercer, S., Beseghi, M., Tamala, M., Heim, K., & Sayram, G. A. (2020). Facing the challenges of distance learning: Voices from the classroom, Relay Journal, 3(2), 185-200. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/030204

[Download paginated PDF version]

*This page reflects the original version of this document. Please see PDF for most recent and updated version.

Abstract

This article reports on the first webinar in the IATEFL Learner Autonomy Special Interest Group’ series of online events dedicated to supporting teachers in this unprecedented and unexpected pandemic situation. Learner Autonomy in the Time of Corona: Supporting Learners and Teachers in Turbulent Days featured a series of talks and open discussion panels, allowing participants to actively share their thoughts and ideas. In the following, the outcomes of the webinar will be discussed.

Keywords: learner autonomy, online learning and teaching, teacher wellbeing, cooperative learning.

The current COVID-19 outbreak has had a tremendous effect not only on our private but also on professional lives: among many others, teachers and students in many countries were suddenly forced to adjust with little or no preparation to a new world where (a-) synchronous online courses are no longer just an option but the norm. In addition to this, teachers and students had to struggle with the shutdown effects on personal freedom, social relations, and mental health.

In the early days of the pandemic, the authors of this paper had the idea of bringing colleagues from different parts of the world together to share their personal and professional experiences and network with colleagues who were all in the same situation. The topics addressed at the event included, among others, ensuring teacher and student wellbeing, fostering student communities, designing and carrying out tasks and projects in online environments, including using social media to promote exchange among learners.

For their spotlight talks, all speakers followed the same guiding questions, namely:

- How do we ensure teacher/learner wellbeing?

- How do we foster foreign language learner autonomy?

- How do we establish a learning community/community of practice and ensure collaboration and interaction among students as well as between teacher and students?

- How do we deal with institutional and individual/personal constraints?

In the following, each of the speakers provides a brief summary on their contribution, shedding light on teaching English as a foreign language in times of a pandemic lockdown. Despite the diverse nature of the speakers’ contexts and work environments, all summaries unearth some common principles and directions of online learning. These encompass, for example:

- professional and personal wellbeing of teachers and students,

- strategies for coping with a sudden transition to online learning, including aspects such as communication, interaction, collaboration, and learner support,

- tools, and platforms for community building,

- principles for designing more autonomous learning environments, curricula, and materials, and

- approaches to reflective practice.

We firmly believe that both future practice and research should be directed towards further exploring these principles.

Teacher & Student Wellbeing in Times of Crisis by Sarah Mercer

In my view, teacher wellbeing is the foundation of good practice. If teachers are not in the right place mentally and physically, they will not be able to teach to the best of their abilities. Fundamentally, teacher and learner wellbeing are two sides of the same coin (Roffey, 2012). Teachers’ emotions are contagious for learners, and teachers also act as role models for wellbeing behaviours that learners can emulate. In this short text I will reflect on the teacher, but attending to learner wellbeing is just as critical, and the ideas below can be adapted for learners.

Many emails that I have received from family, friends, and colleagues during this time have started or ended with some variation on take care during these strange times. There are three themes in the phrase that are critical to understanding our wellbeing at present which are the strange times, self-care, and social relationships. The notion of strange times characterises much of what is threatening everyone’s wellbeing during this crisis. Our normality and the certainties in life that we could rely on have vanished to be replaced by unpredictability and unfamiliarity accompanied by a general sense of unease. Stressors people face include health worries for oneself and loved ones, physical distancing, travel restrictions, restricted services, and uncertainty about what the future (near and far) will look like as well as possibly also financial existential worries (see also MacIntyre et al., under review). It should come then, as little surprise that the current times are stressful for everyone. However, for teachers, there is the added dimension of having to completely rethink one’s teaching and step into a new and, for many, unfamiliar teaching format and role, often with little or no support.

Perhaps the first step to wellbeing is acknowledging just how stressful this all is and giving oneself “permission to feel” (Brackett, 2019). This does not mean indulging the negative emotions, but it is about allowing ourselves to recognise, name, and think about strategies to manage them. To ensure balance we also need to actively seek out the positives in our lives. Perhaps paradoxically, there can be moments of great joy at these times, learning something new, having a successful class, spending quality time with family, and not having to commute to work are just some. One of the strategies with the strongest empirical base for enhancing wellbeing is engaging in regular gratitude practices (Seligman et al., 2005). An example of this would be at the end of every day, just taking a few moments to reflect on all the positive interactions that happened and aspects you appreciate about this day. You might even want to write down moments you are grateful for and keep these notes in a place (e.g., a gratitude jar) that you can revisit when you need reminding of all the good things in your life. If we regularly engage in gratitude practices, we start to train ourselves to notice more readily the positive things around us. Our reality reflects what we devote our attention to and if we only focus on the negatives, we miss the chance to also colour our lives through all the positives that exist every day.

The second part of the email advice concerns the notion of self-care which is critical for educators to prioritise at all times, not just during the crisis.At this moment, in addition to good health and hygiene practices, it also implies learning to prioritise our time and how we use it so that we can comfortably synthesise our work and non-work lives. This means explicitly setting aside time to engage in things which give us pleasure, creating boundaries (possibly physically and temporally) to our work so we ensure that we have enough space and time for our lives away from work non-work lives, attending consciously to our health triangle (i.e., sleep, nutrition, and exercise), engaging in hobbies, giving our minds space to simply just rest, and ensuring we make time to be unavailable and detached from anything work-related (Mercer & Gregersen, 2020).

The final lesson from the email stems from the fact it typically comes from friends, family, and colleagues. One of the great misnomers during this crisis has been the term social distancing. More than ever, we need social closeness but physical distance. Relationships do not just happen, they require effort and attention, but the rewards of social support are considerable. It is worth thinking consciously about people who matter to you, how you stay in touch, and how you spend quality time together. Understandably, as well as social connection, people also need space and time alone. This can be a particular challenge during lockdown, but with empathy and open communication, we can work with those we live together with to find the right balance.

In sum, this crisis has highlighted the importance of wellbeing for teachers and learners. It has given us the chance to pause and become more conscious than ever of just how critical wellbeing is for everyone to be able to function at their best. As teachers, this is our chance to seize the opportunity to develop positive self-care habits now and ensure we maintain these habits as we move into the future.

Teaching Online in Times of Disruption by Micòl Beseghi

Due to the unprecedented measures imposed in Italy to limit the spread of COVID-19, I (as many teachers worldwide) was abruptly shifted into with little time for adjustment. Neither the teachers nor the students were prepared for this sudden change, and we found ourselves in uncharted waters.

In my case, I had just started teaching two courses of English Language and Translation for two different classes of undergraduate students. At first, it seemed that this situation would be temporary but after a couple of weeks it became clear that the university shutdown and online teaching would continue for the entire second semester and perhaps even longer. Although many teachers are well aware of the great potential of technology, when a situation of crisis strikes, it may be difficult to respond immediately and to move on despite worry, stress, and anxiety. The emotional impact has been significant on teachers and students alike, requiring many hours of additional work and a great deal of commitment.

From the very beginning, I realized that I had to stay in touch with my students as my biggest fear was losing contact with them. Therefore, I started to use a dedicated forum on the university platform Moodle and communicate with them daily with the aim of reassuring them that their learning would continue despite the disruption.

The second step was to reorganize the course content, which can be hard to accept, especially after spending much time devising a course syllabus that was supposed to be delivered in a physical classroom. Additionally, teaching online has a different nature and pace (Means et al., 2014), so I had to adjust the original syllabus in terms of both content and assignments. Moreover, such extraordinary events may affect students’ cognitive load, so I reduced the workload and recorded short videos to explain new concepts. Teaching asynchronously, which was chosen because of the large number of students involved, has proved a real challenge, as both teacher and students are deprived of the possibility to interact directly and give and receive instantaneous feedback. The biggest risk is that the teacher becomes a sort of talking head, and students may lose focus and as a consequence cease to learn.

So, how can we keep them engaged? I believe that, now more than ever, it is important to talk about current events around the world, by selecting relevant activities and/or materials. For instance, I asked my students to read and translate articles that address COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, creating a supportive classroom environment is essential to learning online and facilitating discussion can play a fundamental role in such an endeavour. For example, forum discussions can be useful at improving language skills and, more importantly, teachers can offer students quick feedback, encouragement, and motivation to stay engaged.

In learning online, based on my experience, learner autonomy is more important than ever. As we know, it is not about simply asking students to learn independently and to do assignments autonomously because the risk, especially in times of online learning, is that they may feel abandoned and isolated. One should not forget that distance learning here is not a choice but a necessity dictated by the situation.

To conclude, the Coronavirus crisis has brought about a sudden and assumedly unwanted transition in education, confronting teachers as well as students with new challenges, which may turn into opportunities in the future if we are ready to embrace them with an open mind.

Flipped Out – Learner Autonomy and Online Learning in the Time of COVID-19 by Michelle Tamala

COVID-19 presents opportunities to effectively incorporate learner autonomy into both the design and process of remote learning. Education at all levels has been affected and responses have been varied. One response can be labelled emergency remote learning and the other augmented remote learning. In the former, institutions and teachers have needed to create something where either nothing or very little existed, in a very short time. A critical component in this case is the importance of increasing teacher skill levels. The ‘augmented’ mode is where online learning already exists and where institutions have made investments in learner management systems, resources and teacher training. In the augmented model, many institutions have already developed flipped and blended online courses where students prepare for learning out-of-class time, and the course itself blends appropriate use of digital tools with traditional classroom activities. Course writers have often taken the opportunity to write autonomous practices into these courses, giving students more control and ownership as well as space for reflection. In such courses, the main priority is to include video conferencing that allows classes to be taught synchronously and asynchronously in the remote mode, augmenting the existing blended presentation.

Change, especially rapid and unforeseen change, brings challenges. In ‘emergency remote’ learning and teaching, lack of experience and time pressure may lead to a lack of flexibility and creativity in facing the challenges. Firstly, there is the question of whether to try and recreate the physical classroom in the online space. Secondly is the issue of equity of access which is less likely in tertiary institutions where use of devices is more normalised. As well as these issues, the computer literacy of teachers and students needs to be considered in the design of online courses: are they computer literate? Are they confident they can develop the necessary skills? These elements will all influence the design of online courses which anticipate possible issues while at the same time be accessible, engaging, challenging and adaptive. Once a design framework has been decided, other important issues need to be decided. How much of the syllabus can realistically be covered in the online environment? With regards to assessment, is it realistic to maintain traditional assessment or can assessment be changed to give students more control in project-based assessment for example?

To enable the development of learner autonomy in remote learning a number of critical issues need to be considered. Students need to feel a level of control in their online learning and motivated to engage in the activities. This can be achieved by:

Clear uncluttered design with a clear pathway for students to find what they need should be a guiding principle in design.

- Colour and movement are important in enhancing engagement.

- Instructional language needs to be clear and inclusive, written to, not at, the students.

- Resources and activities should be easily accessible and their purpose clear.

- Clarity of expression in all communication of requirements and responsibilities supports engagement in online learning spaces.

- Online courses should not be static, they need to be interactive with clear and frequent spaces for communication between teacher and students, student and student, and student to teacher.

Incorporating the points mentioned above can create a high level of positive communication and develop a supportive, online learning community that consists of independent members.

With time, as teachers and learners become used to the online environment and aware of the affordances of digital technology, it is possible that increased autonomy for both teachers and learners will become a reality. Students learning alone but as part of a learning community can develop autonomous approaches to learning where the design of their online course supports the development of these approaches. Where flipped and blended online courses already exist, the opportunity exists to augment these courses by including video conferencing such as Zoom, Teams, or Google Meet for synchronous class meetings, and asynchronous group work, pair work and individual consultations and counselling which enhance flexibility and individualised learning. Re-examining existing assessment practices will further engage and motivate students. Judicious use of apps such as closed Facebook and WhatsApp groups can help create an effective and supportive learning community linking learners and teachers in positive and creative ways.

It is too early to tell whether remote learning will continue as a major part of education but what is clear is that careful design can ensure that learner autonomy can be a major part of online delivery.

Thematic Groups and Buddy Teams in Long Distance Phases by Katja Heim

Cooperation and collaboration in groups have always played a vital role in autonomous learning environments and also form an integral part of teacher education for learner autonomy (Little et al., 2017). In addition, establishing smaller groups within courses seems to have a potential to keep groups together in long distance phases, e.g. within blended learning scenarios and in pure online courses. In the following, I will share the nature of group work in a blended learning course that I have taught repeatedly at the University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany, and discuss decisions that I have taken in pure online courses during the Corona crisis.

Online elements in courses can be very helpful to stay in touch if students spend a considerable part of a course away from university, e.g. for prolonged school placements. One of the compulsory courses that accompanies such a school placement has thus been designed as a blended-learning course at the University of Duisburg-Essen (Bulizek et al., 2018). During their placements, students are required to make small-scale inquiries into specific chosen aspects within their future field of work. In my courses, these take the form of very low-threshold action research projects (Heim & Gabel, 2020) that aim at fuelling students’ professional development.

In the preparatory courses, prior to the placement, I always encourage students to form thematic groups according to their interests, so that interactions within communities of interest become possible throughout all phases of the projects. Thus, while students mostly have to cope by themselves during their placement, online-interactions within the respective interest groups enable them to share their experiences, give and receive feedback and thus get a broader view on the aspect in question. Also, in many cases, students seem to develop a feeling of togetherness within the groups (Heim, 2018). As an additional step, the groups are divided into smaller sub-groups of 2-3 students (what we refer to as buddy teams) so that students can give each other thorough feedback on the exposés for their projects and on other strategic aspects. According to informal reports from students, these smaller teams often keep regular contacts, albeit often outside the communication channels within the learning management system. Forming thematic groups and buddy teams have thus been reported to potentially contribute to wellbeing in times of distance learning.

In March 2020, due to lockdowns in schools, participants of these courses have suddenly been forced to make drastic changes to their projects in the middle of their internships, thus in some cases interests within groups drifted apart. What was additionally required in those phases were group consultations via videoconferencing. Regular face-to-face meetings were also substituted by videoconferences in order to allow for an as personal contact as possible. Especially in the early days of the lockdown, the technical infrastructure was just being geared towards this type of pure online learning, so the very first attempts were slightly frustrating. However, on the whole, students still provided peer-feedback to each other, there were exchanges of experiences and of potential ideas for alternative projects via forum discussions, and there were still very active thematic groups and buddy teams, which helped each other through the phases of constant adaptations. These additional interactions, again, did not take place via the provided channels in Moodle but mostly via WhatsApp. In many cases, the activities that were initiated within the course resulted in new constellations, outside of established friendship groups, i.e. in this way the formation of thematic groups and buddy teams, has, according to informal feedback, fulfilled its purpose of the formation of interest groups and the promotion of wellbeing.

In the new courses of the summer semester, which have already started digitally, I still largely prefer synchronous meetings via videoconference and my course sizes are of a sufficient number that make this feasible, i.e. there were not more than 35 students in the respective groups. Also, I still regularly integrate prolonged phases of creative group work within the synchronous meetings and, while students are largely but not unequivocally happy about regular synchronous meetings and have also commented on the workload, evaluations have revealed that the opportunity to be creative together in groups is still rated in a very positive way. While it became clear that these online interactions could not fully replicate face-to-face meetings, after this first semester, with all its potential for individualisation, I still feel strongly about supporting learner autonomy within social groups (see Little et al., 2017), even if it is via online communication. And, while I also make use of asynchronous forum discussions etc. and do enjoy reading the reflective entries that are facilitated by asynchronous modes of interaction, I am so far still in the process of working out how to create a real group feeling via these asynchronous interactions in courses held solely online.

Promoting self-directed and collaborative learning through educational technology and social networking ‘in turbulent times’ by Gamze A. Sayram

In the literature there are various studies that illustrate the benefits of online learning. For example, according to Brierton et al. (2016), students feel more comfortable discussing their viewpoints in asynchronous online discussions because they do not have the pressure to respond quickly, they have more time to think about how they respond to the discussions. Communicating asynchronously via online discourse offers students the opportunity to fully express their views and ideas and discuss topics in greater detail (Brierton et al., 2016).

More importantly, students experience meaningful and self-directed learning practices (Choi & Park, 2014; Hrastinski, 2008; Palloff & Pratt, 2013) in online learning environments. For example, during the global epidemic, when teaching online, I asked students to form small groups and choose one TED Talk to share with class each day as an autonomous language learning activity. Each week, students chose their group members, TED Talk topics and the days they will be presenting. They prepared and taught the class important vocabulary about their Ted Talk topic and prepared discussion questions. They had chosen topics relevant to the current pandemic situation, such as isolation, mental health, importance of sleep and how to be courageous to speak to foreigners. These practices were meaningful and engaging and at the same time they were beneficial to improve their EAP learning skills. At the end of the course, students said they enjoyed this activity and found it useful. When I asked them whether they would like to continue this activity in the next course, their response was affirmative.

Asynchronous online learning environments also provide students with opportunities to develop deeper learning strategies (Lowenthal et al., 2017) and increase their self-esteem and autonomous language learning skills.

A facilitating condition in an online learning environment can be a learning community. As Berry (2017) stated, “in a learning community, students work with their peers, instructors, and staff to learn collaboratively and support each other, while pursuing their academic, social, and emotional goals” (p. 2). This sense of community not only increases learners’ class participation, but also promotes their collaborative and cognitive learning skills (Garrison et al., 2010). Furthermore, learning communities provide emotional support and enhance students’ ability to manage stress and their well-being (Stubb et al., 2012).

A lot of what can be found in the literature on online learning is what I personally experienced when on Monday, the 30th of March, 2020, Australia went to a total lockdown and closed all its borders. On that day, we started self-isolating, working and teaching from home. As I started teaching online, through Zoom, I became disappointed and frustrated. There were challenges, such as managing academic integrity in assessments and solving technical problems. While continuing to fulfil the requirements of the curriculum, I found new ways of connecting with the students and helping them to form a community in the classroom. Furthermore, I observed that giving more responsibilities to students, creating independent and collaborative learning activities helped them to become more independent and responsible learners. Realising that online teaching requires a different approach, I prepared independent and collaborative learning activities that were used synchronous and asynchronously.

In an EAP course, I encouraged my students to choose a social networking app to communicate and share information. They decided to create a WeChat group and included all the onshore as well as offshore students. Students used the WeChat platform before, during, and after the class time to communicate and share ideas with each other. I noticed that this worked well because it was an instant way of communication and students were able to talk about their personal and study life. I also noticed that students took responsibility for their learning and worked with their classmates more constructively, as they wrote their reflections in their online reflective learner diaries.

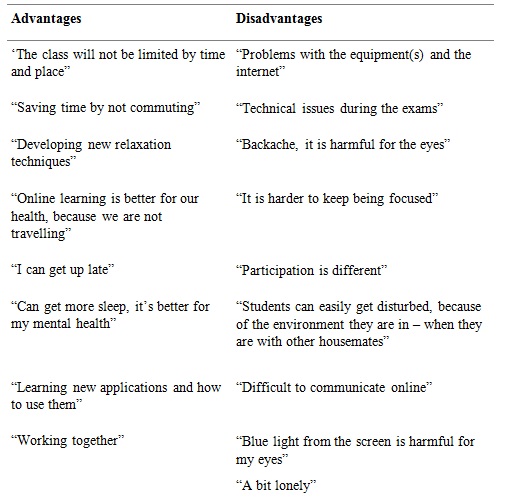

In addition, I prepared weekly online discussions to get them to share their ideas and reflect on the topics discussed during the class time. For these activities, I used our learning-teaching platforms i_Learn and Zoom. Students discussed what they have learned, what was challenging and what they could do better, in groups and shared their ideas with other groups in the class. Further, for each week, I assigned a different student as a leader, note taker and communicator. Students enjoyed taking responsibility and working with others. These activities led to more collaborative work, peer feedback and reflection in class. After four weeks, I encouraged them to talk about the challenges and benefits of online learning through the online discussion forum. See their comments in Table 1.

Table 1

My EAP students’ voices: advantages and disadvantages of online learning

For all these reasons, it is essential for instructors, teachers, managers and institutions to build communities of collaboration and networks for their students to help them become skilful navigators of their autonomous learning and work collaboratively, especially in the current COVID-19 environment.

Looking back at how I overcome the challenges, I am optimistic and look forward to the new opportunities that lie ahead.

Conclusions

The short talks were bolstered by a flood of comments and ideas from a lively audience. Participants not only reacted to the speakers’ inputs but also discussed issues of interest, exchanged information about their current situation, and chatted directly with one another. This gave the impression that a community of practice was formed at a remarkably accelerated pace, which illustrates how important and rewarding it is for us as language teachers to connect with like-minded colleagues and share ideas. In the chat conversation three closely intertwined threads can be identified: reactions to the current situation, the sharing of experiences, and suggestions for tools.

At the beginning of the talk of one of the authors on teacher and student wellbeing, participants were asked to write down the emotions they were going through. The answers in the chat box show that although there are many different emotions and feelings participants had at the time of the webinar, the emotional response was not necessarily negative. Although many of us felt sad, frustrated, anxious, or stressed, many others also expressed positive feelings such as curiosity about new opportunities online. One aspect that was mentioned frequently by a number of participants was the lack as well as the need for a routine to create a healthy work environment and maintain a work-life balance (e.g., “miss my routine”, “need a routine”, “routine is not under my control unfortunately”).

Naturally, the conversation geared towards other topics during the spotlight talks, providing insights into life, professional and otherwise during the pandemic. Recurring themes discussed included, for example:

- the lack of materials and resources, including textbooks, technical equipment, and internet connection,

- the importance of connecting with both students and colleagues,

- the change of traditional teacher and learner roles in various forms of online learning,

- ways of building and maintaining relationships and promoting social learning,

- the human dimension of foreign language learning, i.e. giving students space to express their fears and anxieties,

- opportunities for making online learning more sustainable.

Beside an abundance of ideas regarding approaches and activities, including the flipped classroom learning approach, the use of breakout rooms, and the creation of learning teams, there was a great sense of openness towards the opportunities online learning has to offer. However, future research on teaching practices, teachers and learners’ attitudes, and the development of autonomy, competences and relatedness in the global experience of online teaching and learning is required to shed light on new opportunities to face the challenges of online learning.

Notes on the contributors

Christian Ludwig is currently Guest Professor in the English Department at the Freie Universität Berlin in Berlin, Germany. His research interests include technology in the classroom and foreign language learner autonomy. Together with Lawrie Moore-Walter is co-coordinator of the IATEFL Learner Autonomy Special Interest Group.

Maria Giovanna Tassinari is Director of the Centre for Independent Language Learning at the Language Centre of the Freie Universität Berlin, Germany, where she works as a language advisor and teacher trainer. Her research interests are learner autonomy, language advising, and emotion and feelings in language learning. She is co-editor of several books and author of articles and book chapters in German, English, and French.

Sarah Mercer is Professor of Foreign Language Teaching and Head of ELT at the University of Graz. She is the author, co-author and co-editor of several books in the field of language learning psychology including ‘Teacher Wellbeing’ co-authored with Tammy Gregersen and published by Oxford University Press. In 2018, she was awarded the Robert C. Gardner Award for excellence in second language research.

Micòl Beseghi is a Lecturer in English Language and Translation at the University of Parma, Italy. She holds a PhD in Comparative Languages and Cultures from the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia. Her main research interests include learner autonomy in foreign language learning and advising, and the role of emotions in language learning, and the use of technology in the EFL classroom.

Michelle Tamala has experience both as a teacher and learner of second languages. She taught Indonesian and French in Australian high schools before becoming an ESL teacher. Michelle was Academic Manager for EAP at Latrobe College in Melbourne, Australia; teaching as well as designing curricula and syllaby. Michelle has also managed Independent Learning Centres at University pathway language centres, designing spaces and resources as well as organising teacher education and advising for students.

Since April 2020 Katja Heim has had the position of a temporary professor at the University of Wuppertal in the field of TEFL. In April 2021 she will, most likely, go back to her post as a Senior Lecturer at the University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany. In the article she refers to experiences from her courses in Essen as well as in Wuppertal. In 2007, she received her PhD in the field of EFL Methodology, the focus being on promoting Learner Autonomy in Primary English Teaching. Learner Autonomy is still at the core of her research interests, often in combination with the use of digital media in English lessons, action research in teacher education and inclusive practices.

Gamze A. Sayram has a background in Applied Linguistics and Tesol. She works at the Macquarie University ELC in Sydney, Australia, teaching EAP courses to post-graduate students and mentoring practicum teachers. Currently, she is working towards her PhD in Education. Her research interests include socio-cognitive linguistics, learner-teacher autonomy, and educational technology. She has co-authored and published in academic journals.

References

Berry, S. (2017). Building community in online doctoral classrooms: Instructor practices that support community. Online Learning, 21(2). https://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v21i2.875

Brackett, M. (2019). Permission to feel. Quercus.

Brierton, S., Wilson, E., Kistler, M., Flowers, J., & Jones, D. (2016). A comparison of higher order thinking skills demonstrated in synchronous and asynchronous online college discussion posts. Nacta Journal, 60(1), 14-21.

Bulizek, B., Gryl, I., Heim, K., Reschenbach, U., Schreiber, N., & Stegemann, S. (2018). E-Learning-Szenarien zur Unterstützung einer Forschenden Grundhaltung zukünftiger Lehrkräfte im Rahmen der Studienprojekte an der Universität Duisburg-Essen. Herausforderung Lehrer_innenbildung – Zeitschrift zur Konzeption, Gestaltung und Diskussion 1, 142-163. https://doi.org/10.4119/hlz-2415

Choi, K. O., & Park, Y. M. (2014). The effects of team-based learning on problem solving ability, critical thinking disposition and self-directed learning in undergraduate nursing students. Journal of East-West Nursing Research, 20(2), 154-159. https://doi.org/10.14370/jewnr.2014.20.2.154

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2010). The first decade of the community of inquiry framework: A retrospective. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(1-2), 5-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.10.003

Heim, K. (2018). Das e-gestützte Begleitseminar im Fach Englisch. Blended Learning in thematischen Gruppen und Buddy Teams. In I. van Ackeren, M. Kerres & S. Heinrich (Eds.), Flexibles Lernen mit digitalen Medien. Strategische Verankerung und Handlungsfelder an der Universität Duisburg-Essen (pp. 424-434). Waxmann.

Heim, K., & Gabel, S. (2020). Practitioner research in preservice teacher education and the promotion of teacher autonomy. In: J. Mynard, M. Tamala & W. Peeters (Eds.), Supporting learners and educators in developing language learner autonomy (pp. 40-62). Candlin & Mynard.

Hrastinski, S. (2008). Asynchronous & synchronous E-learning. EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 31(4), 51-55.

Little, D., Dam, L., & Legenhausen, L. (2017). Language learner autonomy. Theory, practice and research. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783098606

Lowenthal, P., Dunlap, J., & Snelson, C. (2017). Live synchronous web meetings in asynchronous online courses: Reconceptualizing virtual office hours. Online Learning Journal, 21(4), 177-194. https://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v21i4.1285

MacIntyre, P., Mercer, S., & Gregersen, T. (under review). Language teachers coping strategies during the Covid-19 pandemic crisis. System, 94, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102352

Means, B., Bakia, M., & Murphy, R. (2014). Learning online: What research tells us about whether, when and how. Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.8.3.333

Mercer, S. & Gregersen, T. (2020). Teacher wellbeing. Oxford University Press.

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2015). Lessons from the virtual classroom: The realities of online teaching. Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025115578237

Roffey, S. (2012). Pupil wellbeing – Teacher wellbeing: Two sides of the same coin? Educational and Child Psychology, 29(4), 8-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.06.009

Seligman, M. E., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410-421. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.60.5.410

Stubb, J., Pyhältö, K., & Lonka, K. (2012). The experienced meaning of working with a PhD thesis. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 56(4), 439-456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2011.599422

This is an excellent overview of several of the challenges we face as educators in the time of COVID. By bringing together voices from around the world, this article demonstrates how global this issue truly is, and how educators as agents reflect and take action to move past the sudden change to something closer to established practices.

I appreciate the various viewpoints that must be taken into consideration as we continue nearly a year into the pandemic. Issues such as teacher/learner wellbeing and how to develop learner autonomy alongside learning communities have become ever more pressing the longer we remain isolated from each other and our institutions. Articles such as this allow for reflection and an opportunity to have a conversation about what we are all experiencing.

If I may add my own experiences to this article, prior to the pandemic I had been, and currently am, learning online for my EdD degree from an American university. The experience of being a student online has helped to provide some understanding of what my own students are currently experiencing. Despite being in courses filled with other educators who are well-versed in the social aspects of learning, creating communities of learning and maintaining our wellbeing online has been a constant struggle. For my current students, it is even more challenging. Just as noted by Kathja Heim, establishing groups and teams has been most beneficial for my own studies and that of my students.

Ultimately, despite the technological hurdles and physical isolation, what matters in my own work and as shown in this article, is communication between students and teachers, students and students, and teachers amongst themselves to be more important than ever for wellbeing, learner autonomy, and overcoming these new individual and institutional restraints. By sharing tools, ideas, as well as feelings, the shift to online teaching and learning can be less of a Titanic and more of an opportunity to move in new directions. After all, due to improved technology and more mobile learners around the world, this kick into online education may be just a hurried version of what will slowly become the new norm.

This leads me to the one question I have for the authors, which may not have an answer yet, is what, if anything, changes you may make in your pedagogy when classes return to face-to-face meetings. Have there been any surprising benefits of moving online you wish to keep? Or if not, why not?

This is a valuable account of how teaching has been performed under ERT in a variety of contexts. The diversity of voices and experiences highlight so many common themes that have been faced this year: how to adapt, how to build relationships, how to stay positive and healthy. Such ideas have surely been in the minds of language teachers over the world.

In reflecting on the article, I have found it useful to extract one key sentence from each contributor which spoke to me the most.

“Explicitly setting aside time to engage in things which give us pleasure” (Sarah Mercer). This is such an important and reassuring point to make. How easy it is for teachers to feel overworked to the point where they feel that they cannot relax, and even worse, guilty about taking time off. The notion of ‘giving ourselves permission’ is one that I need to be reminded of on occasion.

“I believe that, now more than ever, it is important to talk about current events around the world” (Micòl Beseghi). I think this is so true. We cannot pretend that the current events have not changed our students’ lives, and I too have found that students are engaged by articles concerning Covid-19. Students want to talk about this issue, they want to learn more about what is happening in other countries, and they want to compare their experiences to those of others.

“Clear uncluttered design with a clear pathway for students to find what they need should be a guiding principle in design.” (Michelle Tamala). This is something that I could not agree more with. I too have been a distance learner, but one of the key differences between my experiences and my students’ experiences is that I studied part time, taking only one or two courses at a time. Many students studying under ERT are taking a huge amount of classes, and simplicity is the key to helping them navigate their new technology and schedules.

“I am so far still in the process of working out how to create a real group feeling via these asynchronous interactions in courses held solely online.” (Katja Heim). This has also been the most difficult challenge for me also. I wonder whether a solution may lie in recognising that a different group feeling will be created, and considering the positive aspects of such a group feeling. Of course, this is easier said than done.

“Looking back at how I overcome the challenges, I am optimistic and look forward to the new opportunities that lie ahead.” (Gamze A. Sayram). This is a wonderful sentiment to end the article on. Despite the many challenges of the year, there have undoubtedly been many areas in which we have grown. I too look forward to solving the challenges of the future.

Which leads me into a reflective question of my own for the authors to consider: One of the difficulties of this pandemic has been the unpredictable length for which it will continue. I see this uncertainty as being one of the most difficult challenges for both teachers and students. How do we support students (and each other) to deal with this uncertainty that is likely to continue for the foreseeable future?

Thank you all for such a thoughtful piece.