Antonie Alm, University of Otago, New Zealand

Moira Fortin, University of Otago, New Zealand

Abstract

This paper explores the potential of language learning advising through a collaborative reflective analysis of an advising session using the Wheel of Language Learning (WLL) tool. Co-authored by a novice advisor and her advisee, the study examines an advising session in which one author, a language educator and researcher, guides the other, a colleague beginning to learn French as a fourth language. By jointly analysing the dynamics of the advising process, the paper shows how WLL facilitated deep reflection, uncovered connections between different aspects of language learning and encouraged the exploration of new learning strategies. The longitudinal impact of the advising session is evidenced through the advisee co-author’s subsequent progress and reflections. This collaborative study demonstrates the effectiveness of WLL as a visual and interactive tool for promoting learner autonomy and metacognitive awareness, while also demonstrating the value of shared reflection in understanding the advising process.

Keywords: wheel of language learning, learner autonomy, visual advising tool, French, reflective practice, advising.

In this reflective piece, I (Antonie) analyse my experiences as a novice advisor through the lens of an advising session with my colleague Moira, who acted as the advisee. Moira’s role goes beyond that of a participant; she also contributes her perspective on the advising session and reports on its impact on her language learning journey.

This paper is divided into several key sections. First, I give some background to my experience as a language educator and explain what led me to become interested in advising. I then introduce and discuss the Wheel of Language Learning (WLL) tool, explaining its features and potential benefits based on existing literature. Following this, I describe my advising session with Moira, analysing our interaction through three main aspects: the introduction and implementation of the WLL, the navigation between different areas of reflection, and the emergence of powerful questions and insights. The paper concludes with Moira’s own reflections on her subsequent language learning journey and my broader reflections on the advising session’s implications for my practice. Throughout, I reflect on immediate observations and longer-term impacts of using the WLL as an advising tool.

Background and Context: Antonie’s Experience

Languages and language learning have been an integral part of my life. Growing up speaking German, studying in French, and pursuing an academic teaching career primarily in English, I have experienced different linguistic environments. Most of my own language learning has taken place outside of traditional classrooms, including my recent journey to learn Spanish (Alm, 2021). This personal experience has driven my passion as a language educator to create learning environments that motivate students to engage with languages beyond the classroom.

Throughout my career, I have explored different ways in which technology can support language learners in purposeful engagement whether through social media interactions (Alm, 2015), extensive listening with podcasts (Alm, 2013), binge-watching Netflix series (Alm, 2023), or reflective practices such as blogging about their language learning journey (Alm, 2009). I have studied motivational theories and implemented their principles in my lesson design to support learners (Alm, 2006). While many students thrived in this environment, I often felt a missing link.

For instance, in my work with blogs as L2 learner journals (Alm, 2009), I drew on Self-Determination Theory to create a learning environment that supported students’ needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Autonomy was fostered by allowing students to select topics of personal interest for reflection, a sense of competence was supported through clear guidelines, a consistent weekly structure, and informative feedback that helped learners identify areas for improvement and track their progress. Relatedness was nurtured by creating opportunities for learner-teacher interaction through personalised feedback, and by enabling students to share their reflections with classmates and potentially with native speakers, fostering a sense of community and connection to the target language culture. More recently, in my study on L2 Netflix viewing (Alm, 2023), I applied the multidimensional concept of engagement to understand how learners interact with self-selected German Netflix series. By analysing learners’ cognitive engagement (e.g., their strategic use of subtitles and playback controls), emotional engagement (their enjoyment and sense of achievement), and social engagement (their sense of connection to the target language culture), I gained insights into the complex ways learners engage with L2 content in out-of-class learning contexts. This approach to understanding learner motivation and engagement has informed my teaching practice, encouraging me to design learning environments that support multiple facets of the learning experience.

Despite providing a collaborative learning environment and a wealth of resources, I found that students did not always take full advantage of these opportunities. I realised that the key was to make materials personally relevant to learners, which required more direct communication with students. However, I lacked the tools to facilitate these conversations effectively. This realisation led me to the Advising in Language Learning course at Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS). After visiting their self-access learning centre and meeting with advisors in November 2023, I decided to enrol in the course.

Even completing the first module had a significant impact on my approach. The course introduced me to basic counselling strategies and techniques for promoting reflective dialogue (Kato & Mynard, 2016), all of which fit well with my existing research knowledge and provided practical tools. These strategies support meaningful dialogue between advisor and advisee, empowering learners to come to their own insights about their language learning pathways.

I am currently on a year-long teaching sabbatical, which has given me space to reflect on how to implement advising in a university context without an established self-access learning centre. I am excited to continue my study of advising, deepening my understanding of these processes and creating learning environments where language learners feel personally empowered to take ownership of their learning journey.

The aim of this reflective paper is to document and analyse the advising session that resulted from the first module of the Advising in Language Learning course. I describe and reflect on how this experience has influenced my understanding of advising and consider how I might implement these strategies in my future teaching practice.

The Wheel of Language Learning

Inspired by the WLL, a tool adapted from the life coaching Wheel of Life (Yamashita & Kato, 2012), I was eager to explore its potential for promoting learner reflection in an advising session. Having encountered it in course readings and seen it skillfully applied in a video demonstration, I was curious to experience first-hand how this deceptively simple tool could guide an insightful advising session. The WLL has been widely used and discussed in the field of language learning advising, with several researchers and practitioners sharing their experiences and insights in this journal.

The WLL appealed to me for a number of reasons. Firstly, its simplicity provides a clear structure for both advisor and advisee, yet it is flexible enough to allow the learner to develop their thinking in multiple directions. Shelton-Strong and Mynard (2018) describe the WLL as “cognitively rich, but linguistically accessible, allowing for deep reflection on the process” (p. 282). This balance of structure and flexibility seemed ideal for facilitating meaningful reflection.

Another intriguing aspect was its origins in life coaching. Language learning is inherently holistic, affecting and being affected by different aspects of a learner’s life. The WLL as a tool allows us to relate the language learning journey to the broader ‘life journey’ of the learner. This connection can help learners to see how their language goals fit into their overall personal development and life aspirations.

The visual nature of the tool is particularly powerful. As a graphical representation, it can help learners understand the relationships between different aspects of their learning, allowing them to “see where they are at now” (Kato & Mynard, 2016, p. 141), potentially reducing the cognitive load involved in reflection. This seems especially valuable for learners who might struggle with more text-based or purely dialogue-based methods of reflection. Hiney (2022) demonstrated this potential when using the WLL with an advisee who had mild dyslexia. The tool helped broaden the advisee’s perspective on language learning beyond the traditional focus on reading and writing, which had previously caused stress.

By prompting learners to consider multiple facets of their learning simultaneously, the WLL might reveal connections or patterns that neither the learner nor the advisor had previously recognised. Macdonald (2019) found that using the WLL helped his advisee “think logically” and realise that “everything is interconnected” in regard to her satisfaction level for each area of the wheel (p. 57). This ability to help learners see connections between different aspects of their learning journey is a key strength of the WLL.

While I initially saw the WLL as a tool for early advising sessions, Ambinintsoa’s (2020) findings have broadened my perspective on its potential throughout the advising relationship. She found that the WLL can be beneficial at various stages: in first sessions to help students identify specific areas they struggle with, in continuous sessions as a starter when the student doesn’t know where to begin, and for tracking progress when used more than once.

As I embarked on using the WLL in my own advising practice, I was excited to see how this might lead to ‘aha’ moments and new perspectives on the learning process, and I am looking forward to exploring its potential as an ongoing tool for reflection.

The Advisee

The person who volunteered to be my advisee, Moira, was a colleague and friend who teaches Spanish in my department. Moira and I share a passion for teaching and language learning, and we have supported each other’s language learning journeys in the past. As a native Spanish speaker, she had previously helped me with my Spanish, mainly by conversing with me in Spanish. This informal language exchange had greatly contributed to my Spanish development. Now that Moira had embarked on her journey to learn French, I felt it was my turn to reciprocate this support. Our roles had shifted and I was now the more experienced speaker of the target language.

When I told Moira about the course I was taking on Advising in Language Learning, she quickly volunteered to be my advisee. She saw it as an opportunity to deepen her own learning process in preparation for her forthcoming three-month sabbatical in France, where she planned to immerse herself in French language and culture. We agreed to a 60-minute advising session, which was recorded using the Otter transcription tool.

Moira’s linguistic background is complex and fascinating. She is a native Spanish speaker who learned German as a child in Chile, English as a young adult in New Zealand, and is now embarking on learning French, her fourth language. With her language teaching expertise and lived experience of multilingualism, Moira might not be the typical advisee, so I was curious to find out where the WLL would take us.

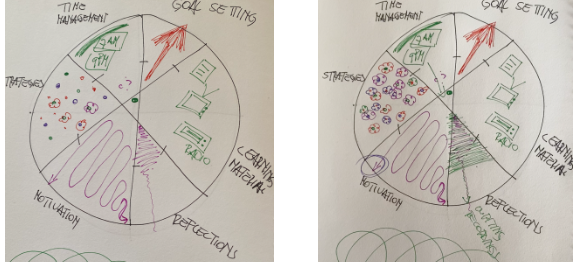

Introducing the Wheel

I invited Moira to draw her WLL (Figure 1), explaining that it would be the tool to guide our discussion, where she would do most of the talking (which she did, 80% according to Otter). She was ready to dive in, explaining that she was “all over the place” (Transcript (T) 1 04:19), but I asked her to first fill out the wheel and think for herself about the different aspects of her learning journey. (For a comparison of Moira’s initial and final WLL, see Appendix A.)

Figure 1

Moira’s Initial Wheel of Language Learning

As I observed her filling out the WLL with all the colours she had available, adding shapes and symbols to it, I wondered if it would be better to let her draw and talk at the same time, as it seemed to help her organise her thoughts. Interestingly, she also added an alternative visual representation, a spiral, illustrating the iterative process and fluctuations during a learning process.

Navigating the Wheel

Transitioning from area to area

I began by complimenting her creative approach and asking her to explain where she had started and why (Figure 2). This open-ended prompt allowed Moira to take ownership of the reflection process and determine our path through the WLL.

A: So, tell me which one did you start with?

M: Time management

A: And why do you think you started with time management? (T2 00:27-00:31)

As she responded to my question, talking about the importance of consistency for language learning, and the struggles to balance her work, life and language learning commitments, she drew a line down to zero, confirming my earlier thought that drawing while taking worked for her. To bring her back on track about how she manages her time for study, I said:

A: So you have a 7am here, that’s very ambitious (T2 02:26)

Figure 2

Time management section

She elaborated on her study practices in the morning, listening to Learn French with News on YouTube to “keep her brain in French” (T2 03:25) as she put it (and I repeated (T2 03:45)), and in the evening, to watching videos for entertainment. I thought it was interesting that she consciously chose different listening and viewing strategies and asked,

A: What do you think, just looking at our wheel here, what does it relate to? It relates to a number of things, I think.

M: Well, the strategies because if that’s why it is super colourful (T2 05:34-05:47)

The answer seemed obvious to her, but raised her awareness of the range of strategies she already used, and further developed through our conversation. Just as she did in the time management section, she continued to draw colourful flowers to illustrate her “growing” awareness of language learning strategies.

For the next transition, I was more direct, as she digressed, talking about her teaching style, intuiting her current high level of motivation.

A: but coming back to your language because you’re, I think you’re quite motivated to learn French.

M: I am, I am

A: So where is that coming from, that motivation to learn [French]

M: Again, back to high school, I guess and discovering that granddad came from France and I was like, okay, so my surname is French, why am I in a German school? (T2 16:45-16:57)

The wiggly line in her drawing (Figure 3) illustrated her long-standing interest in French and a desire to connect with her heritage, which went through phases of high and low motivation. To demonstrate her current level, she circled the arrow reaching level 10.

Figure 3

Motivation trajectory

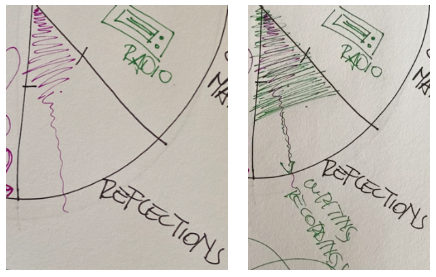

Moving on, the topic of reflection was initiated by her. Looking at the WLL, she directly stated, “I haven’t done much reflection” (T2 25:13). At this stage, we reached a turning point, as she started to consider how a higher level of reflection could play an active part in her learning journey.

A: I think we have heaps of reflection, as we talk about it, but it is dwindling out here a bit, isn’t it.

M: I think I stopped at level 5, and then I was like yeah yeah, I was like, kind of like I know what I’m doing, I know this is working

A: But maybe you want to be able to fill this up a bit more.

M: Possibly. (T2 25:28-25:53)

While her initial reaction was “possibly,” a few minutes later, she came back to the topic.

M: the reflection, it’s going to be filled up massively because during the time that I’m learning French [in France], I’m planning to write a blog […] (T3 05:01)

And the reflection pie (Figure 4) was not only filled up with more colour, but also an arrow that pointed to a new goal: writing and recordings.

Figure 4

Evolution of reflection

Powerful questions

The session presented a few opportunities to ask powerful questions. A particularly powerful moment of realisation occurred when discussing Moira’s plan to write a blog during her upcoming language learning trip to France. While Moira had already decided to keep a blog, I encouraged her to think more concretely about the implementation of this reflective practice. To help Moira transform a general intention into a specific action plan, I posed a series of targeted questions throughout the discussion.

A: what language? (T3 05:12)

A: Is your blog going to be public? Or private? (T3 07:45)

A: So why don’t you write it from the beginning in French? (T3 09:00)

A: Do you know what kind of platform you’re going to use to set it up? (T3 10:46)

A: and how often do you think you’re going to write? (T3 11:06)

These questions prompted Moira to consider practical aspects of implementing her blog, from language choice to privacy settings, platform selection, and writing frequency. The discussion of the blog led to a major breakthrough insight for Moira about the potential of audio reflection. When I rephrased Moira’s idea and emphasised the word “write” Moira had a visible aha-moment. She paused, processing this new possibility, and then enthusiastically explored the idea of recording her reflections orally, linking it to her previous successful use of this strategy in other contexts. Here is a longer extract of the transcript, which contextualised the emergence of this powerful moment.

M: So maybe I will do it just once a week and maybe so that can write a little bit more and, and get some anecdotes because that’s the that’s the fun part when you start making better really looking forward. You know, when you start saying the wrong words or the you’re discovering, oh, I’ve been saying this word completely backwards for three weeks and you go like, okay, now I learned that, you know, but looking for all those anecdotes as well. They’re going to help because that’s what flushes up the language.

A: So you put anecdotes, so you want to write [emphasis on write] your blog?

M: Yeah. [Pause] Oh, that’s an interesting thought.

A: I didn’t say it. Tell me you thought.

M: Speaking it.

A: Aha

M: Uhhh – Like a podcast that’s very nerve racking. I might, I might, I might. I won’t be read or maybe do both. You know, writing something as they hear, listen, listen to this. You know, kind of like maybe adding some some speaking exercises or not exercises but kind of like some speaking reflections. And that is a really interesting idea, because when I was doing my PhD in Theater Studies … (T3 11:35-12.27)

Moira linked the idea of using audio recordings, or producing a podcast, to her practice of recording herself to review plays during her PhD. I followed up on the benefit of this strategy for her learning style and she replied:

M: Speaking things

A: yeah

M: organises my thoughts. (T3 13:58-14:01)

At this stage, I felt, we had come full circle, starting with her statement of being “all over the place” and having reached a new stage where the half-filled pie in reflection had become part of her new learning goal.

I finished the session with two questions. To my first question, on how she thought the session went, she responded,

M: Oh, that was amazing. I feel like this reflection section… I’m going to fill it up somewhere there [add the words: writing and recording]. Yeah, it’s just grew. (T4 00:06-00:12)

Our conversation had allowed her not only to revise (and reflect) on what she had done, but helped her to develop a plan, which also involved learning new things about herself,

M: I will have to get used to how my voice sounds in French. (T4 00:47)

And to my final question, about how she feels about herself, she simply answered:

M: Oh, I’m gonna use a word that is super trendy at the moment: empowered. (T4 02:57)

Moira’s Reflections: A Journey Shaped by the WLL

As a testament to the impact of our advising session and the WLL, Moira shares her reflections on her language learning journey:

On the of 27th of September I gave a talk about my research entitled Les productions théâtrales scolaires de Rapa Nui comme réponses communautaires à la mondialisation: Représentations de ‘A’amuTuai par le lycée Aldea Educativa Hoŋa’ao te Mana at the Centre de Recherche et de Documentation sur l’Océanie CREDO at the University Aix Marseille. The original plan was to give my talk in English but after being encouraged otherwise I gave my talk in French. When we talked about the WLL, four months ago, giving a talk in French, within an academic context, was not an idea I had in mind. I left Dunedin with a clear vision of what my language journey would look like. The WLL helped me to keep track of the different strategies I could use to expand and grow the use of French, for example movies, books, radio, reflecting about my own learning process and recording myself for my weekly blogs during my eight weeks course period. Because I had a clear path, my progress was significant and surprisingly quick. I started with a A2 level, after thee weeks I was moved up to B1 which I finished with a grade of 89.5/100. In addition, I had two weeks lessons at a B2 level, which I endeavour to continue. Now that I am travelling back home, I’m looking again at the WLL, reflecting on this new stage I am begining now. In a way I am starting a new WLL, strategizing ways of, at least, keeping my level of French. These strategies may include keep up reading, watching movies and listening to the radio. I am also counting on my colleagues at LACU [Languages & Cultures programme] to create a French club for students to practice their speaking. I will definitely join in. Other ideas may include writing a blog in French, but I am not sure as this may be very time consuming, but I definitely send voice messages to my French host to keep the relationship and my French speaking abilities growing.

Moira’s progress is further documented in her blog, where she reflects on her experiences with the WLL and her subsequent language learning journey. You can read her first blog entry here: https://papatekena.wordpress.com/2024/06/30/getting-ready/

Reflections on the Advising Session

Moira’s reflections provide some evidence of the lasting impact of our advising session and the WLL tool. Her account not only confirms my initial observations but also reveals how the insights gained during our session translated into significant language learning progress over the following months.

The most significant realisation, in my view, was how Moira’s reflections on her current learning strategies and experiences transformed into a vision for her future L2 self (Dörnyei, 2009). As Moira explored her use of writing and audio recording for reflection, she began to envision how these practices could shape her identity as a learner and speaker of French. This shift from reflection on past and present experiences to a projection of a future self was a tremendously powerful moment in the session. Moira’s comment about getting used to how her voice sounds in French (T4 00:47) encapsulates this transformation, as she anticipates embodying a new linguistic identity. Her subsequent achievement of giving a talk in French, something she hadn’t even considered during our session, demonstrates the power of this visioning process.

Throughout the session, I found that Moira responded well to subtle prompts and questions, allowing me to facilitate her reflective journey without being directive. This experience taught me the value of suggesting rather than telling, and then observing where the learner takes the conversation. Moira’s responsiveness reinforced the importance of active listening in creating a space for learners to open up and explore their experiences deeply.

I was particularly satisfied with how WLL supported Moira’s reflective process. The visual nature of the tool, combined with the interactive process of completing it, seemed to complement Moira’s way of thinking and processing information. This approach enabled her to make connections and uncover insights in a non-linear way. The act of drawing and annotating the WLL appeared to facilitate Moira’s thought process, allowing her to explore different aspects of her language learning journey simultaneously. The WLL provided a structure for our conversation while still allowing flexibility for Moira to guide the direction and pace of the session.

While the session with Moira was highly successful, I recognise that she may not represent the average language learner I encounter in my university teaching context. Many of my students may not yet have developed the same level of metacognitive awareness and openness to reflection that Moira demonstrated. They may also have different abilities, learning styles, and backgrounds that impact their approach to language learning.

This highlights the importance of developing a diverse toolkit of advising strategies and tools to accommodate a wide range of learner needs and preferences. Just as the WLL proved effective for supporting Moira’s reflective process, other learners may benefit from different visual, auditory, or interactive tools that correspond to their learning styles and stages of development.

Moving forward, I am keen to expand my repertoire of advising techniques and resources to better support my students on their journeys toward becoming autonomous and fulfilled language learners. Moira’s experience has shown me the potential long-term impact of effective advising and the use of tools like the WLL. It has reinforced my belief in the power of reflective practices and the importance of helping learners develop a clear vision for their language learning journey.

Notes on the contributors

Antonie Alm is an Associate Professor at the University of Otago, New Zealand. Her research explores the intersection of language learning, learner autonomy, motivation, and technology. Her recent research examines how reflective practices can enhance autonomous language learning in both formal and informal contexts.

Moira Fortin is an actress and lecturer at Languages and Cultures at the University of Otago (Aotearoa/ New Zealand). Her research focuses on Indigenous theatre, particularly in Rapa Nui (Easter Island), and the intersection of language, performance, and cultural identity. Her work explores how language and translation influence theatrical expression in bilingual and intercultural productions.

References

Alm, A. (2006). CALL for autonomy, competence and relatedness: Motivating language learning environments in Web 2.0. The JALT CALL Journal, 2(3), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.29140/jaltcall.v2n3.30

Alm, A. (2009). Blogging for self-determination with L2 learner journals. In M. Thomas (Ed.), Handbook of research on web 2.0 and second language learning. Information science reference (pp. 202–222). IGI Global.

Alm, A. (2013). Extensive listening 2.0 with foreign language podcasts. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 7(3), 266–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2013.836207

Alm, A. (2015). Facebook for informal language learning: Perspectives from tertiary language students. Eurocall Review, 23(2), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.4995/eurocall.2015.4665

Alm A. (2021). Apps for informal autonomous language learning: An autoethnography. In C. Fuchs., M. Hauck, & M. Dooly (Eds.), Language education in digital spaces: Perspectives on autonomy and interaction (pp. 201–223). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74958-3_10

Alm, A. (2023) Engaging with L2 Netflix: Two in(tra)formal learning trajectories. In D. Toffoli, G. Sockett, & M. Kusyk (Eds.), Language learning and leisure: Informal language learning in the digital age (pp. 379–407). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

Ambinintsoa, D. V. (2020). Using an advising tool to help students go beyond “just learning”, Relay Journal, 3(2), 221–228. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/030207

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9–42). Multilingual Matters.

Hiney, G. (2022). Helping a language learner gain self-confidence and awareness through advising. Relay Journal, 5(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/050105

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

MacDonald, E. (2019). Reflection through dialogue: Conducting a mentoring session with a juku colleague using the ‘Wheel of Reflection’ tool. Relay Journal, 2(1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/020106

Shelton-Strong, S. J., & Mynard, J. (2018). Affective factors in self-access learning. Relay Journal, 1(2), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010204

Yamashita, H., & Kato, S. (2012). The Wheel of Language Learning: A tool to facilitate learner awareness, reflection and action. In J. Mynard & L Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context (pp. 164–169). Longman.

Appendix A

Moira’s Initial and Final Wheels of Language Learning